Taking Root

The environmental justice movement is rooted in communities of color: grassroots organizations pushing back against the immediate and long term consequences of environmental injustice.

Grassroots environmental justice activism addresses specific issues in a community. Injustices such as the deliberate siting of landfills, incinerators, or hazardous waste disposal sites near communities of color prompts those affected to band together to address the harm, advocate for support, and push for change.

Communities often organize when legislation or regulation fails. They identify the source of the harm as well as the regulations and procedures that fail to protect them. Lawyers, scientists, and community organizers are sought out by communities and can provide support by connecting them with other experts of helping them to navigate the complex web of legal and political structures that surround the issues and perpetuate them.

Environmental racism exists across the United States, and its impact can be seen in our local communities.

When one person is impacted by environmental injustice, an entire community is likely facing similar threats. There are many different ways a community can band together to make change. Below we explore local injustices and the ways in which those communities banded together to make change.

Activism emerges through protest, consulting experts, learning to navigate the law, and asserting your right to know what is going on in the world around you. The goal is to ensure that necessary safety measures are taken, and protective regulation and infrastructure are put into place to prevent harm before it happens.

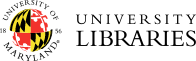

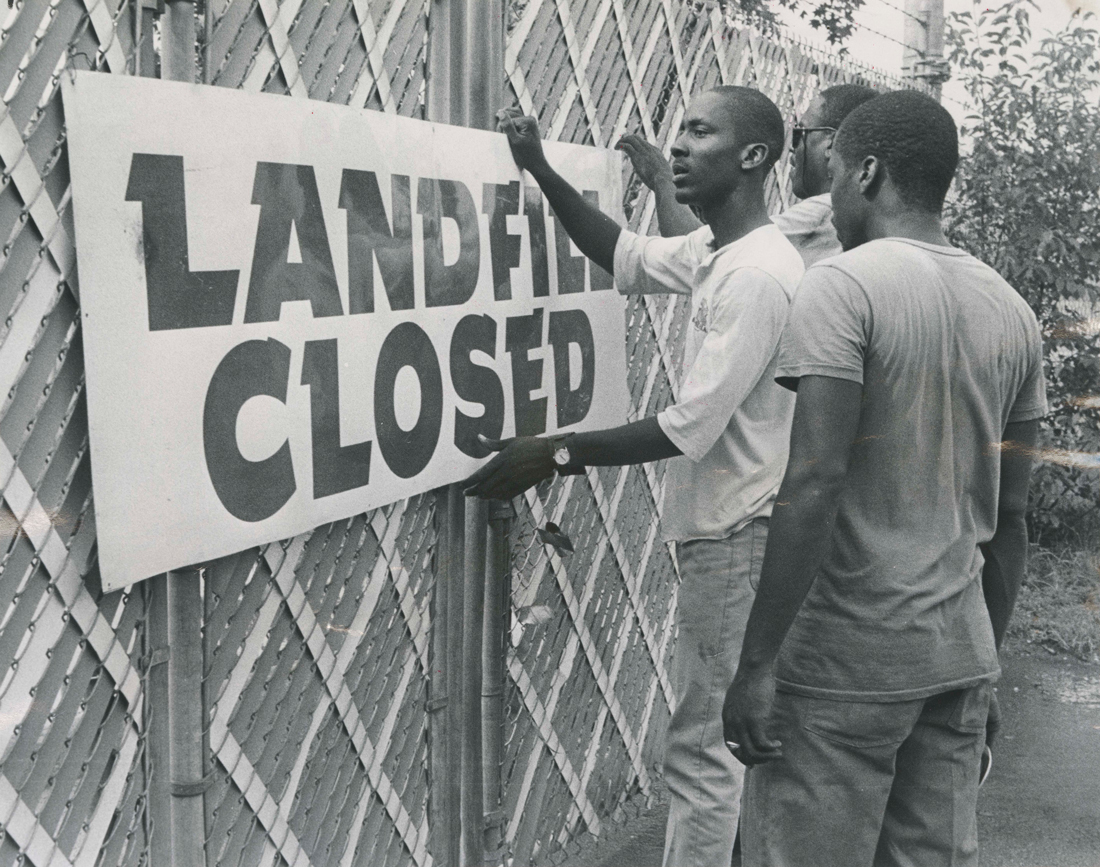

Pollution in Maryland, n.d. Baltimore Environmental Center records, UMD Special Collections and University Archives.

Pollution in Maryland, n.d. Baltimore Environmental Center records, UMD Special Collections and University Archives.

Local Case Studies

Baltimore, Maryland

Environmental racism not only occurs when corporations target communities of color while siting hazardous waste landfills, but it can also emerge in the form of neglect. Neglect can mean lack of access to sanitation systems or proper infrastructure to aid in the time of crisis such as flooding or extreme heat.

Below are items that display Baltimore landfills and the ways in which Black communities disproportionately faced lead poisoning, as seen in studies from the 1990s–in just one city, we see environmental racism in so many forms.

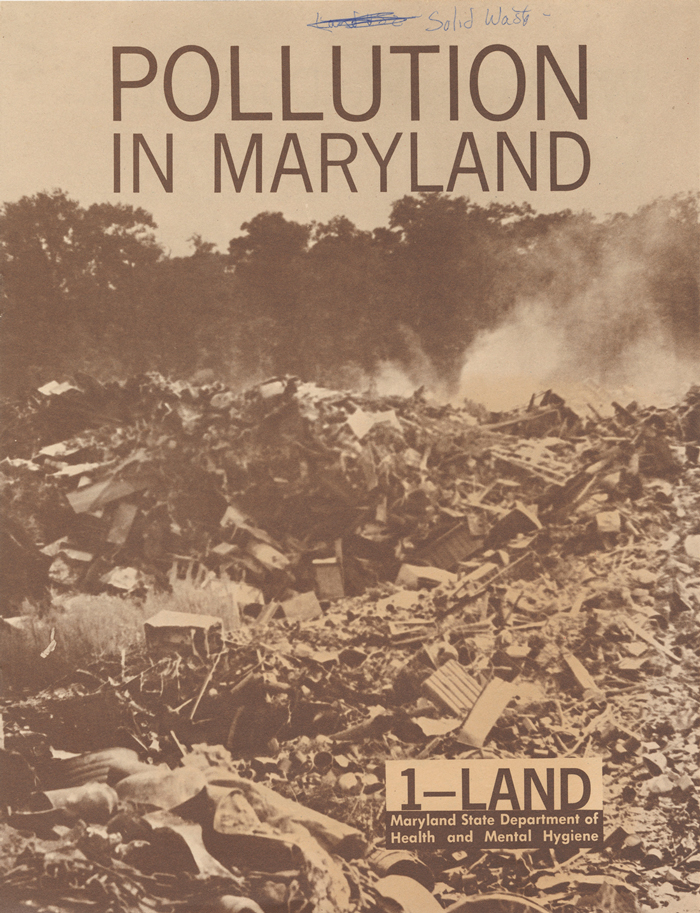

Browning-Ferris workers post sign announcing the closing of the Norris Farm Landfill, 1985. Baltimore News American collection, UMD Special Collections and University Archives.

Browning-Ferris workers post sign announcing the closing of the Norris Farm Landfill, 1985. Baltimore News American collection, UMD Special Collections and University Archives.

From Lead Poisoning: Strategies for Prevention, 1984. Mayland Room Stacks, UMD Special Collections and University Archives.

From Lead Poisoning: Strategies for Prevention, 1984. Mayland Room Stacks, UMD Special Collections and University Archives.

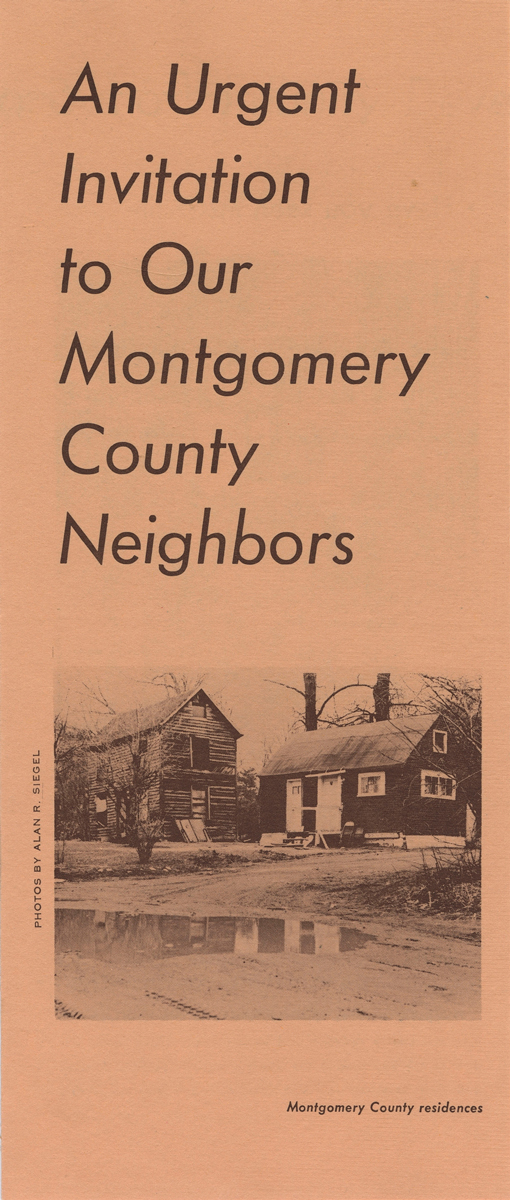

Montgomery County, Maryland

The rise of suburbia during the 1950s and 1960s encircled and often pushed out historically Black communities across the nation. In Montgomery County, Maryland, dozens of Black communities faced urban renewal programs, rising living prices, lack of sewer access, and lack of trash clean up. Here, we see how Black communities in Montgomery County spoke out against this environmental racism.

Pamphlet cover for Scotland Community Development Inc., 1960s. David and Elizabeth Scull Papers, UMD Special Collections and University Archives.

Pamphlet cover for Scotland Community Development Inc., 1960s. David and Elizabeth Scull Papers, UMD Special Collections and University Archives.

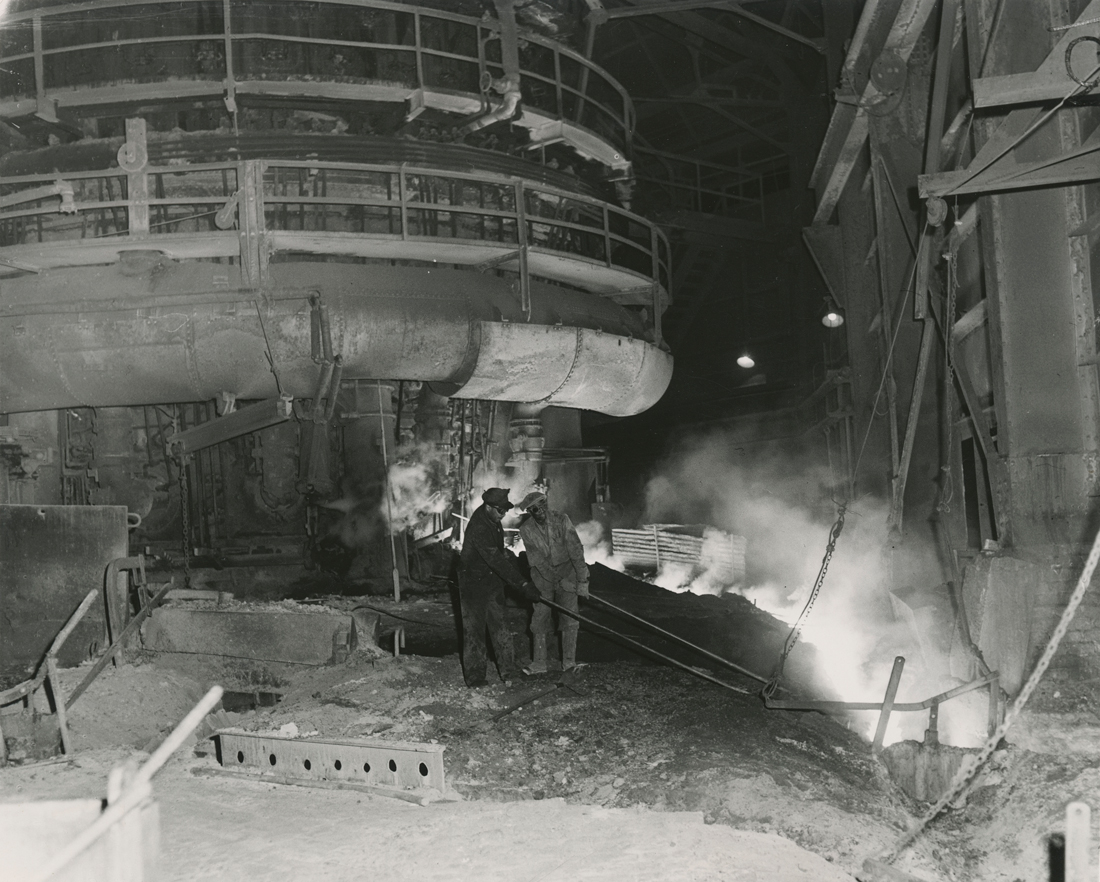

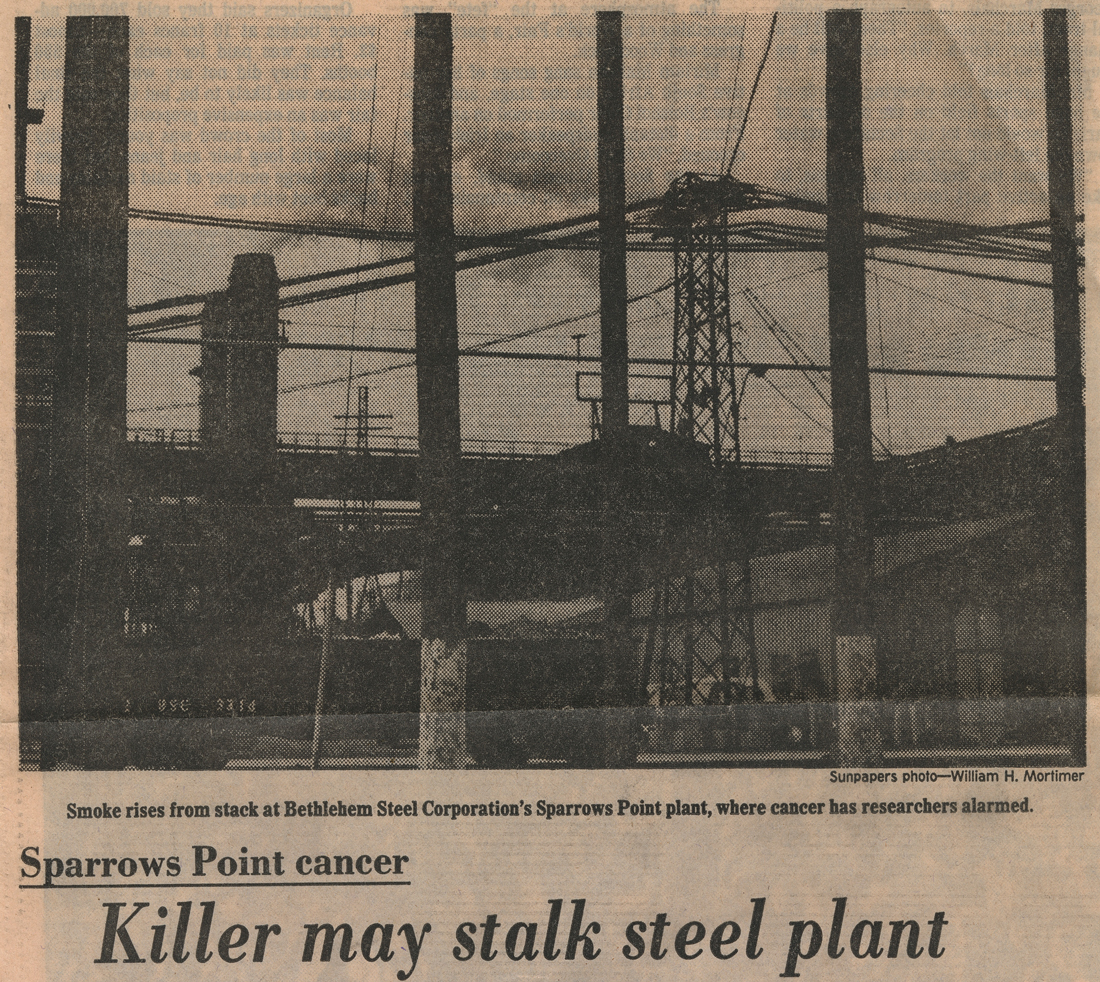

Bethlehem Steel, Sparrows Point, Maryland

Environmental injustice did not just exist in communities where people lived and can also be seen in the workplace. The 20th century saw the rise of the steel industry where workers faced daily hazards including toxic chemicals and extreme heat. The use of asbestos in the steel mills led to mesothelioma and other types of cancer.

Bethlehem Steel was located in the Baltimore suburb of Sparrows Point, Maryland and was once the largest steel mill in the world. Not only was the steel mill in general a dangerous place to work, but workers of color, often Black and Latinx workers, were frequently the ones doing the more hazardous labor, meaning a stronger likelihood of injury and long term health effects caused by the job. These workers also lived in the mill complex.

Bethlehem Steel workers, n.d. Baltimore News American collection, UMD Special Collections and University Archives.

Bethlehem Steel workers, n.d. Baltimore News American collection, UMD Special Collections and University Archives.

Cropped image of Baltimore Sun article: “Killer may stalk steel plant”, 1977. Baltimore Environmental Center Records, UMD Special Collections and University Archives. Click to see full clipping.

Cropped image of Baltimore Sun article: “Killer may stalk steel plant”, 1977. Baltimore Environmental Center Records, UMD Special Collections and University Archives. Click to see full clipping.