Ann Corrick: A World-Class Journalist Earns Her Place In History

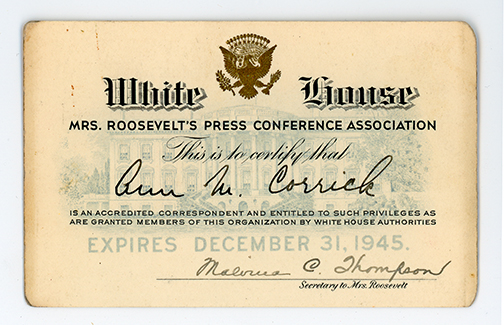

"She was called the Detroit Bombshell. This was because she was from Detroit and because she was a whiz. Everyone always predicted that Ann Corrick would be a success at whatever she did because there was an intensity about her which is rare." 1

World War II expanded job opportunities for young women, many of whom came to Washington, DC, to be secretaries, aka "government girls," for the wartime administration. But when journalist Ann Corrick arrived in the nation's capital in 1943, fresh from the University of Texas, she had much higher ambitions.

Over the next 24 years, Corrick would cover breaking news in Congress, at the White House, the State Department, and during national conventions, presidential campaigns, and elections, achieving many "firsts" along the way. The Ann Corrick papers at UMD document her work and demonstrate the tenacity, bravery, and intelligence with which she forged a remarkable career impressive for any individual, let alone a woman working in a male-dominated field that was at best inhospitable.

A Young Reporter Gets Started

Ann Corrick started working as a reporter when many newsmen were working overseas. "I was lucky. I came here during the war," Corrick once commented. "I really came east to seek my fortune in New York. I was really quite confident, having just got out of school. But I stopped in Washington to visit some former schoolmates of mine who had located here and were making a success of their jobs." 2

She decided to stay and soon joined four other Texas women sharing an apartment in Southeast Washington. Hired by Transradio Press Service, which supplied news to individual radio stations by teletype and shortwave, Corrick hit the ground running. "I was just thrown into the business of covering government," she said in a 1956 interview. "My first assignment was the major tax revision during the war period, and I had to sink or swim." 3

Corrick said she was given a hard time by the men covering Capitol Hill during her first year. "They used to trip me when I was racing for a phone. It was rough. But I just kept my mouth shut. It was business, and you've got to take it." Her grit in the face of discrimination likely developed at a much younger age. 4

Early Life

Ann Marjorie Corrick was born in 1921 and grew up in Grosse Pointe, Michigan. As an adult, she declined to talk about her childhood in interviews. "She came from a family of engineers – masons, home and commercial builders," her niece and namesake wrote in an email to us, adding that Corrick's father's construction business had been successful before the Depression.

The family was hard-hit by the economic downturn and struggled. To make matters worse, both her parents died while Corrick was still a child: Her mother in 1927 and her father in 1932. Two older sisters helped raise her afterward.

Corrick's life dramatically improved when she enrolled at the University of Texas in Austin. "I went down to Texas with my brother, who was a petroleum engineer. He wanted to scout the oil industry, and I really went down just to take up time with him. But I saw the campus of the University of Texas, and I liked it, and I stayed."

She started out majoring in architecture and taking singing lessons, according to a 1958 profile. Still, once she began working at the college newspaper, The Daily Texan, she quickly changed her focus to a major in journalism and a minor in economics. She became president of the student chapter of Theta Sigma Phi – then a professional sorority for women majoring in journalism, now the Association for Women in Communications – and graduated in 1943.

Her niece remembers, "Ann always mentioned that her college roommates were her best mothers as she had little guidance before then." Liz Carpenter, a reporter who later became the first woman executive assistant to Vice President Lyndon Baines Johnson, then press secretary for his wife Lady Bird Johnson, was one of those roommates.

Dress for Success

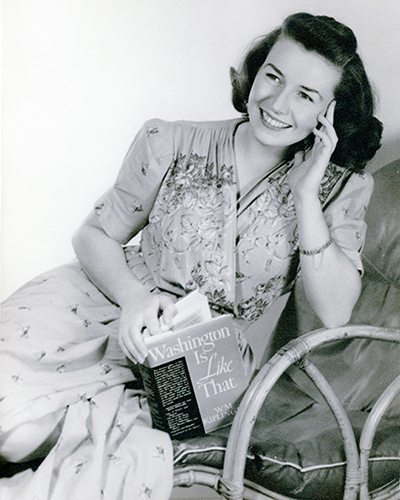

While the shortage of newsmen provided job opportunities for women reporters, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt gave them access to the White House. She set aside one hour each week when newswomen – and only women – could attend a press conference with her. A 1944 article in the Austin American describes Ann Corrick among those ambitious newcomers who enjoyed this opportunity and then reassured readers that her drive to succeed did not compromise her womanhood.

"Miss Corrick is typical of the newer crop of newspaper women in Washington," the article noted. "Extremely grateful to the past women of the press who battled for their rights, they are determined to do a man's job but still look like a woman in feminine suits and dresses." 5

However carefully attired, her regular beat covering the House of Representatives included interpreting the intricate tax proceedings and covering the House on Unamerican Activities Committee's hearings on communism in Hollywood. In 1945, Corrick also covered President Roosevelt's funeral and Vice President Truman's subsequent swearing-in for Transradio. 6

The first sign of her acceptance by the men of the Washington press corps, she said in a 1956 profile, was when they began opening doors to let her go first into news conferences. "Then I knew they were accepting me, not as a woman, but as a working colleague," she said. 7

After Transradio folded in 1951, Corrick worked as a producer for two NBC radio and television programs, American Forum, a public affairs panel discussion, and Youth Wants to Know, a variation with high school and college students on the panel. She left that job a year later and continued as a freelance journalist. 8

Corrick then wrote for CBS news reporter Eric Sevareid's radio program. She was a correspondent for WLW and WLWT in Cincinnati and also worked for the Washington-based newspaper Roll Call, reporting legislative news and covering congressional elections nationwide. In 1952, Corrick was elected treasurer of the Radio-Television Correspondents Association, representing reporters covering Congress. At that time, she was the first and only woman elected to the association's governing board. 9

By 1955, she worked for an enterprising radio and television station in New Orleans, WDSU, reporting on Congress. She produced Dateline Washington, a television program the station aired locally. In 1956, she provided WDSU with live radio coverage and commentary from the Senate gallery and filmed interviews for the television station's Sunday Supplement program. The live coverage was the first time a single station carried hearings direct to local listeners. It also marked the first time a woman originated a broadcast from the Senate Caucus Room. 10

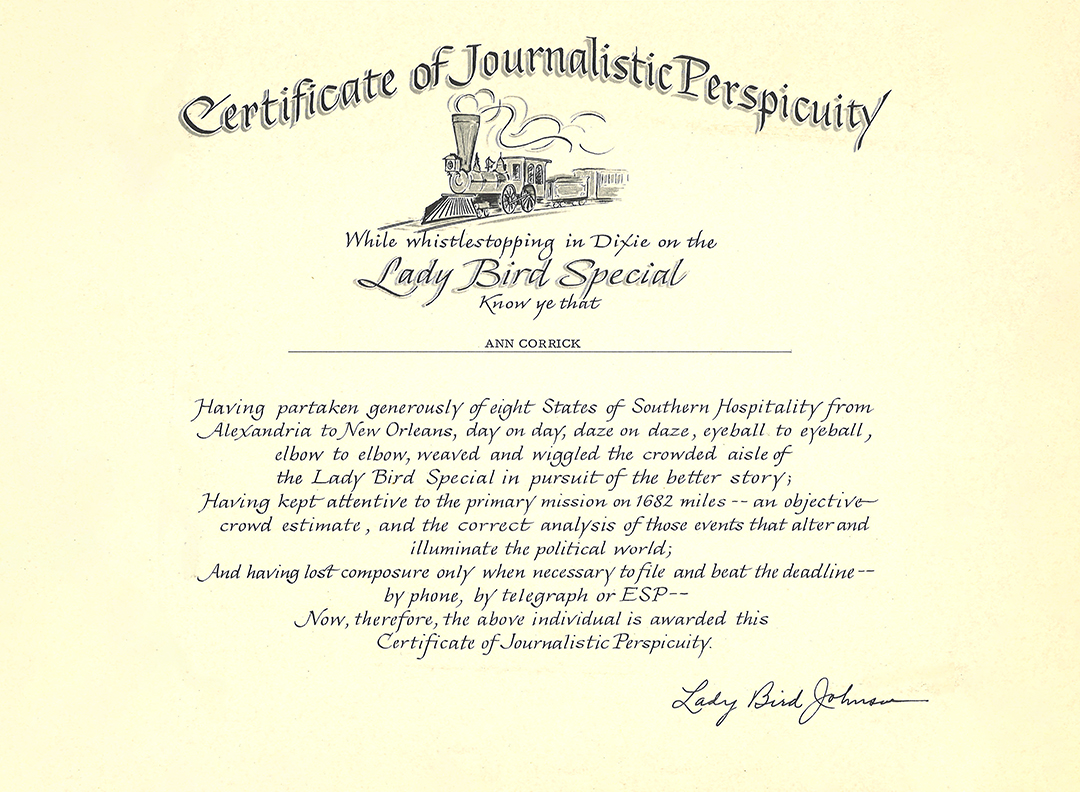

Corrick had worked freelance for Westinghouse News for a year when Rod MacLeish, Washington bureau chief, hired her as assistant bureau chief in 1958. In addition to writing and broadcasting daily spot news, she produced and moderated a half-hour weekly interview program – Washington Viewpoint. Special assignments included traveling with presidential candidates Kennedy and Nixon during the 1960 campaign and with Mrs. Lyndon Johnson on the "Lady Bird Special" train in 1964. 11

Corrick became the Radio and TV Correspondents Association president for the 1961-62 term, the first woman to hold that position. At the annual dinner following her election, Vice President Lyndon Johnson escorted her to the head table where President John F. Kennedy and Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn were waiting to congratulate her. Later, at a reception, she was serenaded by the Harvard Glee Club and invited to tea at the White House by Mrs. Kennedy. 12

In 1962, the Association for Women in Communications honored Corrick with the National Headliner Award for her work in radio and television. She was also appointed to the National Association of Broadcasters’ Freedom of Information Committee.13

Passed over twice for the Washington news bureau chief, her opportunities may have seemed limited – even as Westinghouse radio stations adopted 24/7 news formats. When she eventually left Westinghouse in 1967, she had reported on every Democratic and Republican national convention since 1944. 14

After Journalism

Corrick then joined the United States Information Agency's foreign service. She first served as a congressional liaison officer in the Office of Protocol at the U.S. Pavilion at the 1967 World's Fair in Montreal. She then spent two years in Saigon working for CORDS (Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support), a "pacification" program during the Vietnam War. 15

Her exact duties are difficult to pin down. Corrick's later resume describes her job as "assistant information officer." The 1969 Foreign Service List, published by the Department of State, lists Corrick as a "psychological operations officer." Whatever her duties, she reported directly to Ambassador William Colby, who later became Director of the Central Intelligence Agency.

The years in Vietnam took a heavy toll, according to her niece. "She arrived home malnourished and shell-shocked and looked quite exhausted," she said. "She was a different person after she returned to Washington." Corrick likely had difficulty relaunching her career as a broadcast journalist. She freelanced for several years, finally leaving the city in 1974 and moving to California.

"My dad had health problems, so she agreed to move near my parents," her niece told us. "She spent more time with family. Eventually, she worked in my father's office in Santa Cruz but appeared physically weak. My Mom passed away and Dad and Ann saw each other regularly and both retired in the 1990s."

When Corrick later had a stroke, she never fully recovered and died in January 2000 at the age of 78. "Ann never married and devoted her life to her career," her niece said. "She was self-made for sure."

Items from the Ann Corrick papers

Pass for First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt's women-only press conferences.

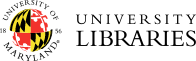

Ann Corrick on the set of Youth Wants to Know

Newspaper article "The 9th Column"

Certificate for participation in the “Lady Bird Special,” a a whistle-stop tour across several states by First Lady Lady Bird Johnson in October 1964. It was a four-day, 1,628-mile train ride across eight Southern states to campaign for her husband, Lyndon Baines Johnson.

The Vietnam Civilian Service Award was presented to employees of the United States Foreign Service for sustained superior performance while under threat of physical attack or harassment.

Created by Jim Baxter (jmbaxter@umd.edu) of Special Collections in Mass Media and Culture, University of Maryland Libraries.

1 The opening paragraph of a guest commentary signed only "AB" for "The Ninth Column" in the Austin American, May 10, 1961

2 Ann Corrick, interview fragment, undated, found among the Group W audio tapes

3 "Radio News Services," Broadcasting Magazine, July 10, 1944; "It Was Tough, She Says," New Orleans Item, January 4, 1956

4 "It Was Tough, She Says," New Orleans Item, January 4, 1956

5 Sutherland, Liz. "First Lady’s Weekly Press Conference Gave Capital Newspaperwomen First Real Chance," Austin American, March 19, 1944

6 "It Was Tough, She Says," New Orleans Item, January 4, 1956

7 Ibid

8 "Air-Casters," Broadcasting Magazine, Sept 3, 1951; "Air-Casters," Broadcasting Magazine, Sept 9, 1952

9 Logansport Pharos-Tribune (Indiana), Dec 4, 1952; Broadcasting, March 2, 1953; Television Digest, January 2, 1954; Congressional Record, June 14, 1956; Lexington Advertiser (Mississippi), June 7, 1962; Isabelle Shelton, "News Beat Scored by Ann Corrick," Washington Star, January 19, 1958

10 "WDSU Marks ‘Firsts’ in Hearing Coverage," Radio Daily, April 6, 1956; "WDSU-AM-TV Coverage of Senate is Intense," Broadcasting, April 16, 1956

11 Broadcasting, April 7, 1958; "Radio Stations," Sponsor, April 12, 1958

12 "First Woman Elected By Radio, TV Writers," Fort Worth Star-Telegram, January 12, 1961 (Newspapers.com); Television Digest, January 16, 1961; Broadcasting, January 29, 1961; "The 9th Column," The Austin American, May 10, 1961; "Short Tales from Longhorns," The Alcade (University of Texas at Austin alumni magazine), October 1961

13 "Journalism Unit Gives 3 Awards," Baltimore Sun, June 7, 1962; "National Theta Sigma Phi Meet to Begin Wednesday," San Antonio Express And News, June 17, 1962; "News Women Honor Headliners," San Antonio Light, June 22, 1962; Television Digest, June 25, 1962; Smith, Hazel Brannon, "Through Hazel Eyes," Lexington Advertiser, June 28, 1962; "Broadcasters Seek Widening of Rights," New York Times, November 22, 1961

14 Lexington Advertiser, June 7, 1962.

15 Broadcasting, July 17, 1967; Foreign Service List, U.S. Department of State, 1969; The Biographic Reporter, U.S. Department of State, July 1970; The Alcade, May 1968; December 1970.