From Amos n’ Andy to Civil Rights:

The Inclusion of Blackness in Commercial Radio Broadcasts

Researching the history of racial representation in commercial radio is challenging. Records documenting radio history, particularly airchecks (recorded broadcasts), are scattered, incomplete, or entirely lost. Until recently, comprehensive radio historiographies have given little voice to people marginalized or excluded from the industry. The thousands of audio reels preserved in the Library of American Broadcasting collections, however, provide a more complete account of this history, which enables us to explore patterns of biases and inequality, and trace the development of more inclusive practices. The audio clips below illustrate how the inclusion of Blackness slowly evolved in commercial network radio in various guises between the 1930s and 1960s. These recordings also invite further inquiry into many related subjects, people, and events of their respective eras.

Contextualizing the recordings

Since commercial networks first developed in the late 1920s, their station boards, staff, and on-air talent were overwhelmingly white and male. The majority of their nationally syndicated programming targeted white middle-class audiences. Primetime favorites of the 1930s such as The Jack Benny Program, The Baby Snooks Show, The Shadow, Gangbusters, and The Fred Allen Show garnered big ratings and plenty of sponsorship, becoming mainstays for their respective networks. If Black characters appeared on these programs at all, it was usually in the form derived from minstrel tradition in which they were portrayed as "mammies," servants, simpletons, or criminals. Race was a subject mined for white entertainment and little more.

U.S. involvement in WWII heralded a significant shift, and the white supremacist regimes in Europe that they were fighting against forced Americans to take a harder look at their own attitudes towards race. The networks also realized that Black support was essential to the war effort, so they created some special programs designed to raise awareness of racial inequalities in the U.S. and highlight Black contributions to American culture. After WWII, commercial networks reported on racial issues in their national news broadcasts with more regularity, which increased dramatically during the Civil Rights era. While these broadcasts were still aimed at white listeners and primarily reported by white male voices, the industry signaled their acknowledgment that racism wasn't just a Black problem but an American problem.

United States. Office of Education. Freedom's People advertisement, ca. 1941.

W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.

Listen to the audio

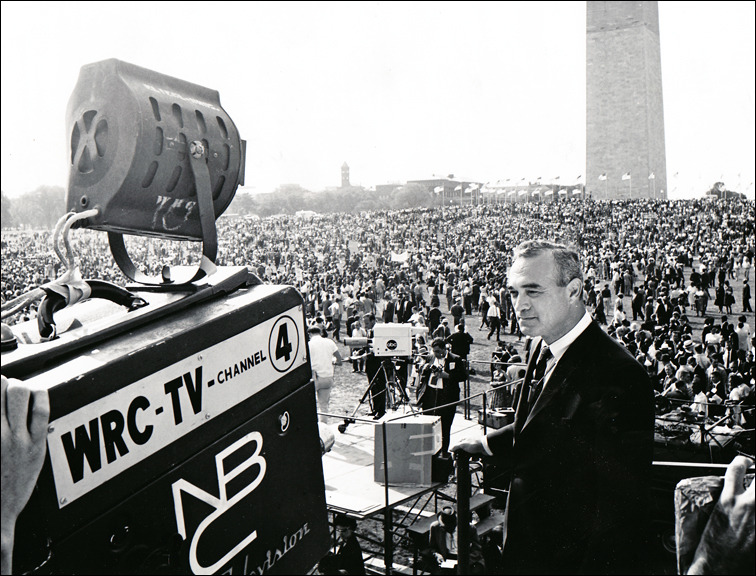

Amos 'n' Andy, 1929

Black musicians often appeared on local radio programs in major cities, and performers like Ethel Waters and Duke Ellington were among the rare exceptions who had syndicated programs on network radio. But it was Amos' n' Andy, the most popular radio program during the late 1920s and early '30s, that ostensibly portrayed Black culture for most of America. The show was created, written, and voiced by two white actors, Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll. Through “vocal minstrelsy”, Gosden and Correll played a variety of Black characters on the program, relying on racial stereotypes for humor but also casting them in sympathetic light. The show was even popular among some Black audiences because it was as close as they could get to representation on primetime radio. Others denounced it as crude and offensive. Amos n’ Andy eventually ran for 32 years, from 1928 to 1960, and also as a television program (with Black actors) from 1951 to 1953. Pressure from the NAACP and other groups was the primary factor in the show's eventual cancellation.

Freedom's People episode 1, 1941

Freedom's People in 1941 was an 8-part series on NBC radio exploring Black history and contributions to science, industry, sports, music, arts, and the nation more generally. Created by Ambrose Caliver, a Black official with the U.S. Department of Education, Freedom's People featured leading Black intellectuals, artists, and activists. This audio is the first episode, which dealt with African-Americans' contributions to American music, and featured appearances by W.C. Handy, Josh White, Paul Robeson, and Noble Sissle.

“What the Well-Dressed Men in Harlem Will Wear”, 1943

"What the Well-Dressed Men in Harlem Will Wear" was a song-and-dance number from This Is The Army, an all-male touring revue designed to boost morale in the U.S. during World War II. Warner Brothers later filmed it, and the number on film includes a cameo by champion boxer Joe Lewis. The Black performers are dressed in military uniforms, while the backdrop behind them features more stereotypical characters in zoot suits. "Well-Dressed Men in Harlem" was the only number in the show in which these performers appeared (watch a video of the performance). However, earlier in the show, there was a full-scale minstrel number with white soldiers in blackface.

"Open Letter on Race Hatred", 1943

"Open Letter on Race Hatred" was a special CBS radio program in response to race riots in Detroit, Michigan, on June 21, 1943, where 35 people were killed, 600 injured, and 1800 arrested. The program, written by William N. Robson, stressed that the German and Japanese press used these riots for propaganda purposes. The program closed with 1940 Republican presidential candidate Wendell L. Wilkie, who emphasized the "rights of the Negro” and the need to eliminate fascism at home and abroad. The program later won a Peabody Award.

WTOP program on racial relations, 1947

After WWII ended, Black veterans found that their sacrifices did not entitle them to equal opportunities in peacetime. "Racial Relations – a Preliminary Report" was a special radio program in response to the recently-released report of the President's Committee on Civil Rights on Washington's WTOP-AM. Henry Mustin, the station specialist in District affairs, sought comments from officials about specific issues cited in the report, including segregation in education and housing. Most of those interviewed were reluctant to make any comment, and others refused to respond.

WRC program on Montgomery bus strike, 1956

Sparked by Rosa Parks' arrest, the Montgomery bus boycott was a 13-month mass protest against racial segregation on the public transit system of Montgomery, Alabama. Washington's WRC radio, owned and operated by NBC, celebrated its 45th anniversary with a series of short segments on the station's news reporting history. This clip features highlights from the year 1956, which includes an odd juxtaposition of Doris Day singing "Que Sera, Sera" with Martin Luther King, Jr. announcing the bus strike's successful resolution. It suggests a still-evolving approach to treating racial issues with appropriate gravitas.

Freedom Riders news reports, May 24 and 25, 1961

Freedom Riders were civil rights activists who rode interstate buses through the southern states in 1961 to protest segregated bus terminals. On May 24, "The World Today" on the Mutual radio network reported on Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy's request for a "cooling off" period in Southern conflicts with the Freedom Riders, followed by an eyewitness account from reporter John Jay in Mississippi. On May 25, John Scott in New York described the response to the Attorney General's request from the NAACP and the Mississippi governor, and reporter Chuck Elliott gave an eyewitness account from Alabama.

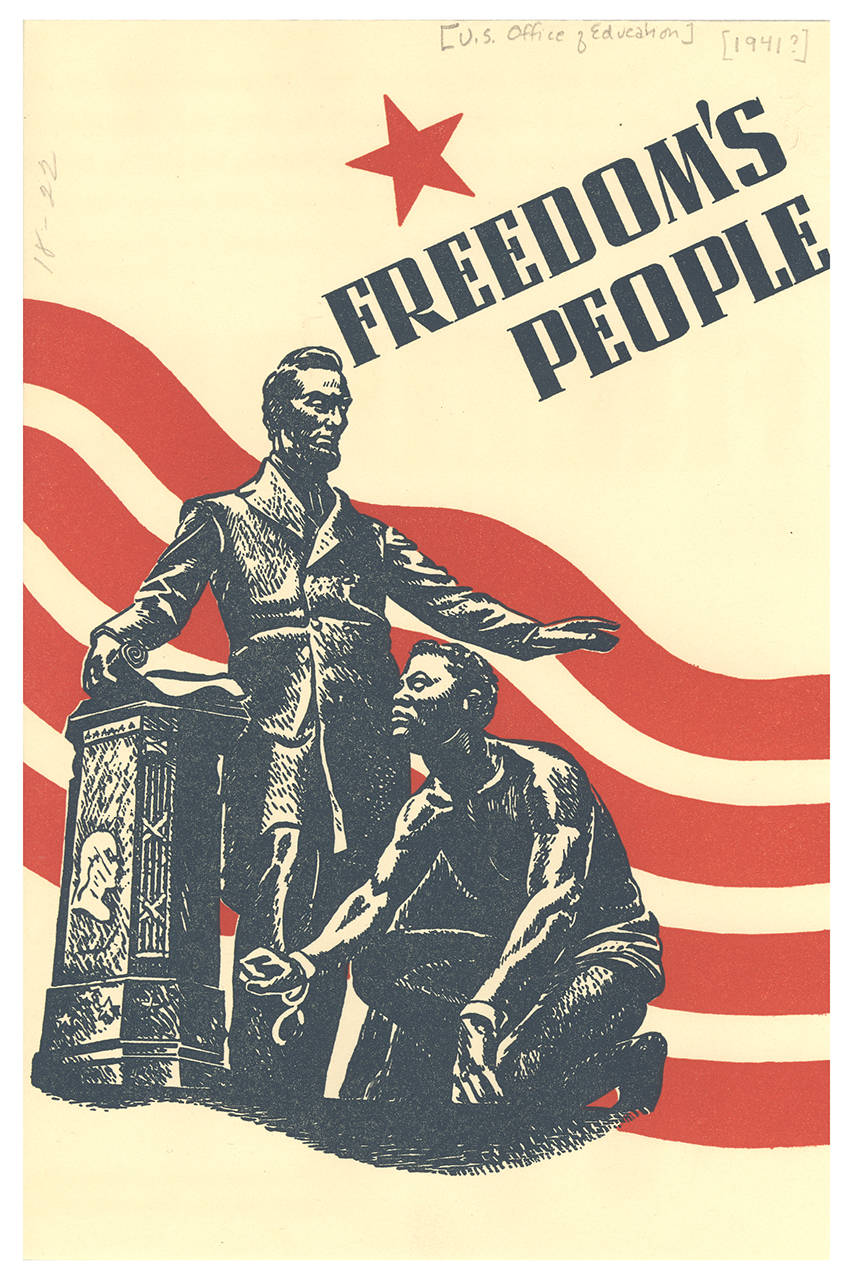

March on Washington coverage, 1963

The Mutual radio network's Sid Davis reports from the Lincoln Memorial, describing the speakers and the enthusiastic crowd at the August 28 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Marian Anderson sings "He's Got the Whole World in His Hands," followed by speeches from John Lewis, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and Walter Reuther, President of the United Automobile Workers of America. A portion of a speech by Floyd McKissick, National Chairman of the Congress of Racial Equality, is heard at the end of the audio.

Malcolm X comments on civil rights bill, 1964

On March 25, 1964 the Senate voted 67-17 to formally take up the civil rights bill. The following day, African-American Muslim minister and Black nationalist Malcolm X observed their debates from the visitor's gallery. In the first of two news conferences afterward, he remarks that the proceedings seemed to him to be "just some more political chicanery." He corrects one reporter, "It’s not 'the Negro cause' when you try to bring about independence for all people in this country. Any thinking person is working for the so-called American cause. You’re not working for my cause when you try and practice what you preach."

Sen. Dirksen interview after Civil Rights Bill passage, 1964

Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen (R-IL) played a vital role in the politics of the 1960s. Here, he answers questions from reporters after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which he helped write. This landmark bill – first proposed by President John F. Kennedy and signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson – ended segregation in public places and banned employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. assassinated, 1968

African-American clergyman and civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. was fatally shot at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968. This audio includes: a brief radio announcement on April 4 that the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. has been shot and killed; Vice-President Hubert Humphrey interrupts a congressional dinner to make a spontaneous speech on the tragedy, Mutual reporter Hal Sessna reports until President Lyndon Johnson is ready to speak from the White House.

1963 March on Washington, over the television news crew’s shoulder, NBC News’ Martin Agronsky. The event was broadcast on both radio and television.

LAB Collections, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Maryland Libraries.

NBC television correspondent Ray Scherer overlooks the vast crowds attending the 1963 March on Washington as he speaks into a camera provided by WNBQ. The event was broadcast on both radio and television.

LAB Collections, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Maryland Libraries.

Additional Resources

An academic blog on African Americans And Early Radio was created in the early 2000s by Donna Halper of Emerson College in Boston, MA.

One of the largest and richest archival collections of Black music and culture is housed at Indiana University: Archives of African-American Music and Culture

The University of Florida news blog has an article on how Black Radio Played a Strong Role in Shaping Civil Rights.

An outstanding audio documentary on the history of Blacks in radio, produced by Public Radio Exchange (PRX) sourced much of content from the AAAMC at Indiana: Black Radio: Telling It Like It Was, 25th Anniversary Edition radio documentary.

A digital magazine on public history called Not Even Past, created by academics in 2010, published a piece on Eddie Anderson, the Black Film Star Created by Radio.

African-American Intellectual History Society, a blog founded by scholars in 2014, published an article about History, Memory, and the Power of Black Radio.

Online magazine and travel company Atlas Obscura posted an article on How America Got Its First Black Radio Station.

New York Public Radio Archives & Preservation published an article about One of the County's Earliest African-American Radio Programs on WNYC 1929-1930.

American Public Media produced a 50-minute audio documentary on Blacks’ increasing involvement in radio during WWII called Radio fights Jim Crow.

Radio performers Freeman Gosden (left) and Charles Correll (right) reading a script for their situation comedy Amos 'n' Andy.

NBCU Photo Bank/AP

Screen capture of “What the Well-Dressed Men in Harlem Will Wear” from the 1943 film version of the stage show This Is the Army.

This was the only integrated WWII company in the armed forces, although the cast was still segregated, and this was the only number performed by the Black men.

Created by Laura Schnitker (lschnitk@umd.edu) and Jim Baxter (jmbaxter@umd.edu) of Special Collections in Mass Media & Culture, University of Maryland Libraries