Students Fight to End Segregation

“Racial segregation must be seen for what it is, and that is an evil system, a new form of slavery covered up with certain niceties of complexity.”

—Martin Luther King Jr.

Segregation: A Difficult Truth

After dismantling slavery in the United States, a new system of oppression and dehumanization was established. The creation of state and local statutes that legalized racial segregation began in the immediate void left by ending slavery. Institutions of higher education were also not immune to these Jim Crow laws and this new form of white supremacy.

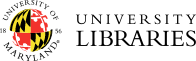

Harry S. Cummings and Charles W. Johnson became the first Black men admitted to the University of Maryland Law School in Baltimore and graduated in 1889. Unfortunately, a growing change in the political winds placed new pressure to stop the acceptance of Black students into dental, law, and medical schools in the Maryland system. Arthur Pue Gorman, Maryland representative in the U.S. Senate launched a campaign the same year these men graduated to stoke fear over the notion of Black people making too many political gains. In 1890, John L. Dozier and William A. Hawkins were expelled from the Law School after the university received several complaints from white students and the administration. A policy banning Black students was formally put into place the following year.

The flagship campus in College Park remained racially homogenous, except for a few international students. While Black students were not allowed to attend classes at the main campus, there is a long history of Black laborers affiliated with the institution's early years, such as the Dory family, whose family members worked on campus for multiple generations.

Arthur P. Gorman. The Parties and the Men, or Political issues, 1896. [Place of publication not identified]: Robert O. Law.

Man standing with barrels and watering cans, no date. Department of Entomology records.

In 1935, Donald Murray attempted to disrupt the Jim Crow system and request admission to the law school. After several rejections explicitly based on race, Murray garnered the support of the NAACP and was represented by Civil Rights attorneys Charles Hamilton Houston and Thurgood Marshall. Eventually, the Baltimore City Court issued a Writ of Mandamus requiring the university to admit Black applicants to the law school under the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. Murray began classes and graduated by 1938. Despite this ruling being upheld in the State Court of Appeals, College Park and the rest of the university system remained racially segregated.

The Fire This Time

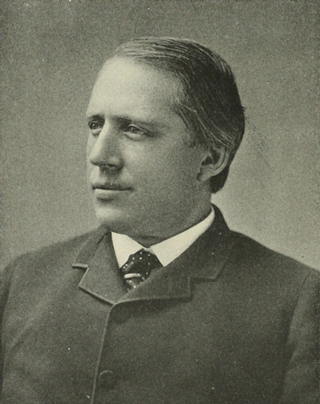

The Princess Anne Academy, located on the Eastern Shore, opened in 1886 as a preparatory institution for Morgan College. In 1919, the Princess Anne Academy was absorbed by the Maryland system in an attempt “to comply with the Second Morrill Act of 1890, which required states to provide equal educational opportunities for Black students in agriculture and the mechanic arts”, but the budget was minuscule in comparison to what the white institutions were receiving. Furthermore, the institution did not have collegiate standing, let alone the charter to provide legal studies.

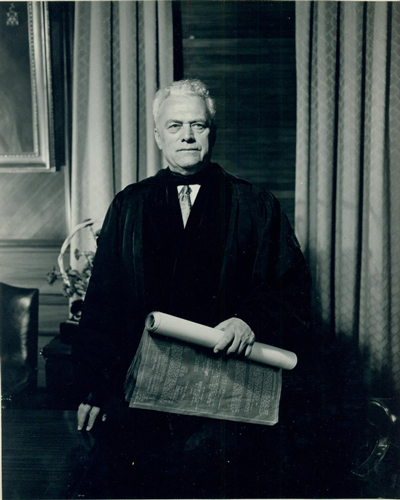

Harry Clifton Byrd served as president of the university from 1935-1954 and was instrumental in expanding the physical campus, strengthening its athletic program, and increasing its enrollment and budget, but he was also an ardent segregationist. Black students, like Donald Murray, were refused admission to UMD and encouraged to apply to the Princess Anne Academy.

The Princess Anne Academy lacked an adequate budget for sustaining a campus of its size. The buildings were made with wooden frames (a significant fire hazard) and the campus had dirt roads until 1935. On March 31, 1941, a heater in one of the rooms exploded. A total of 55 women were with their children when they became engulfed in flames. Reports indicate that women were jumping from the windows, many with their children in hand. A total of six people died, including a 3-year-old boy. After the fire, an investigation indicated that many of the campus buildings were unsafe.

As the embers from the Princess Anne Academy settled and cooled, the fight for Black students to be accepted more broadly into the Maryland system continued. Although a small number of Black students were admitted to the Graduate Studies Program in the College of Education, these students were not permitted to come to the College Park campus and were taught by professors that traveled to Bowie to provide their coursework.

Harry Clifton Byrd served as president of the university from 1935-1954 and was instrumental in expanding the physical campus, strengthening its athletic program, and increasing its enrollment and budget, but he was also an ardent segregationist. Black students, like Donald Murray, were refused admission to UMD and encouraged to apply to the Princess Anne Academy.

The Princess Anne Academy lacked an adequate budget for sustaining a campus of its size. The buildings were made with wooden frames (a significant fire hazard) and the campus had dirt roads until 1935. On March 31, 1941, a heater in one of the rooms exploded. A total of 55 women were with their children when they became engulfed in flames. Reports indicate that women were jumping from the windows, many with their children in hand. A total of six people died, including a 3-year-old boy. After the fire, an investigation indicated that many of the campus buildings were unsafe.

As the embers from the Princess Anne Academy settled and cooled, the fight for Black students to be accepted more broadly into the Maryland system continued. Although a small number of Black students were admitted to the Graduate Studies Program in the College of Education, these students were not permitted to come to the College Park campus and were taught by professors that traveled to Bowie to provide their coursework.

Princess Anne Academy, Class of 1894. University of Maryland Eastern Shore, Special Collections.

“If we don’t do something about Princess Anne, we’re going to have to educate them at College Park, where our girls are.”

—Harry Clifton Byrd

Harry Clifton Byrd standing in academic garb holding a rolled blueprint, circa 1920-1940. Sterling Byrd collection.

The title “The Fire This Time” is credited to Jesmyn Ward’s The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks About Race. New York: Scribner, 2016.

We Will Not Be Turned Back: The 1950s

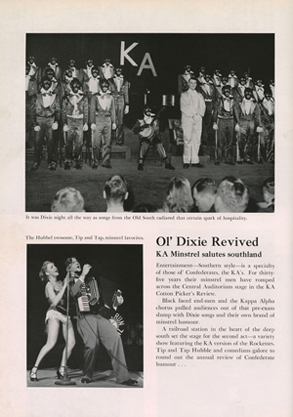

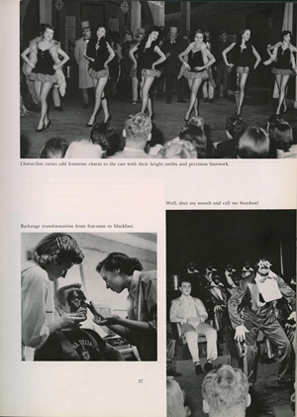

In the 1950s, the University of Maryland, previously known as MAC, continued to engage in traditions that supported racialized stereotypes. The Kappa Alpha Annual Cotton Pickers Minstrel and Review was viewed as a campus highlight. The show included comedy routines, dance, songs, and various guest performers. The mere existence of Black students on campus served as a counter narrative to racist ideas that permeated this period in the university’s history.

Donald Murray once again played a pivotal role in desegregating the campus. This time, he fought alongside Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP to end the university’s continued rejection of Black students. These applicants were pushed to out-of-state institutions with promises of scholarships. In 1949, Murray and Marshall filed a suit on behalf of Esther McCready, who had applied to the nursing program in Baltimore, Parren J. Mitchell, who applied to the graduate program in sociology, and Hiram Whittle, who sought undergraduate admission into the engineering program.

One of the final legal blows to segregation was the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education on May 17, 1954. Brown v. Board of Education was a multi-decade campaign, including five lawsuits against school districts in Kansas, South Carolina, Delaware, Virginia, and the District of Columbia. The final Supreme Court decision overturned the 1896 Plessy vs. Ferguson case that endorsed “separate but equal.”

The Kappa Alpha Annual Cotton Pickers Minstrel and Review. Terrapin, 1953 & 1956. University Publications collection.

Timeline

-

1886

The Princess Anne Academy, located on the Eastern Shore, opens as a preparatory institution for Morgan College.

-

1887

Harry S. Cummings and Charles W. Johnson become the first Black men admitted to the University of Maryland Law School in Baltimore.

-

1890

John L. Dozier and William A. Hawkins are admitted to the law school.

-

1891

After several complaints from white students and the administration, a policy banning Black students is put into place.

-

1893

John F. ‘Frank’ Dory begins his career at the MAC; the Dory family continues to work on campus for multiple generations.

-

1935

Donald Murray is denied admission to the law school and urged to attend Princess Anne Academy.

Harry Clifton Byrd inaugurated as President of UMD.

-

1941

A devastating fire breaks out in a room at Princess Anne Academy. A total of six people die, including a 3-year-old boy. After the fire, an investigation indicates that many of the campus buildings are unsafe.

-

1948

John Francis Davis, Myrtle Holmes Wake, and Rose Shockley Wiseman are admitted into the Graduate Studies Program in the College of Education.

-

1949

Donald Murray and Thurgood Marshall file a suit in 1949 for Esther McCready, Parren J. Mitchell, and Hiram Whittle.

-

1951

Davis, Wake, and Wiseman become the first Black students to attend the commencement ceremony at College Park.

-

1954

The Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education on May 17, 1954 overturns the 1896 Plessy vs. Ferguson case that endorsed “separate but equal”.

-

1958

Elaine Johnson (Coates) becomes the first African American undergraduate to graduate.