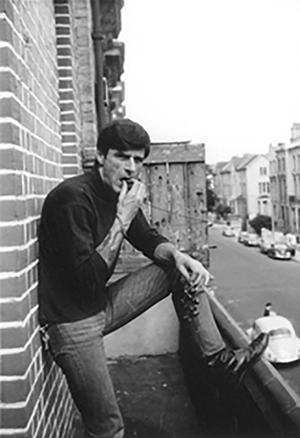

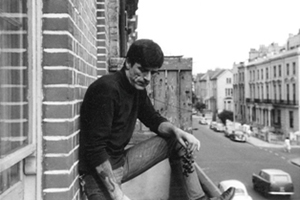

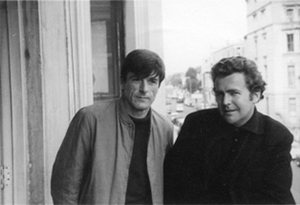

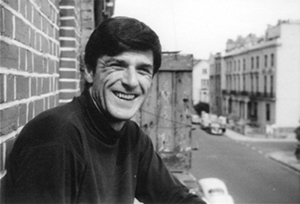

Photographs, circa 1964-1965

Reminiscences by Marcia Tanner

Thom Gunn's 1964-1965 London sabbatical leave from University of California, Berkeley, coincided with my first year in England. I arrived in April 1964 from California to join my fiancé Tony Tanner, a Fellow of King's College, Cambridge. Thom came later in the year. That fall I moved from Cambridge to London to work as an editorial assistant at Encounter, a journal of ideas and literature that was ultimately outed as a CIA front. My boss, the poet Stephen Spender, was Encounter's literary editor.

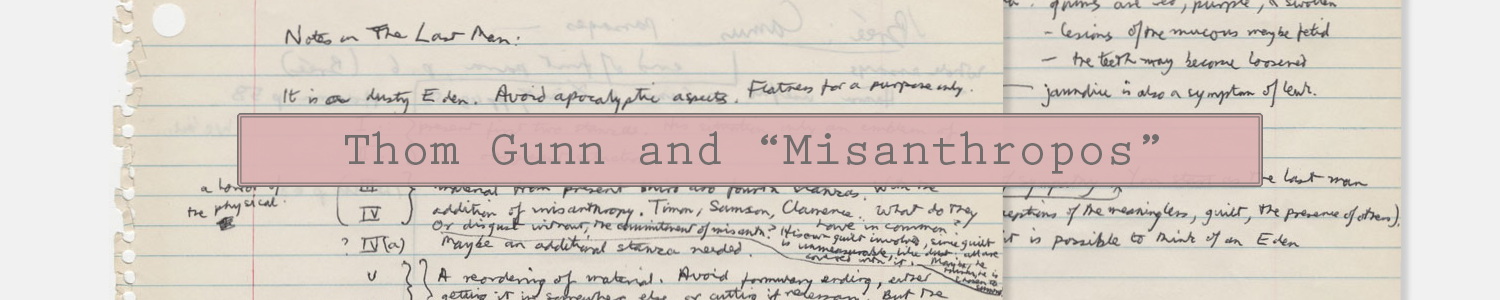

During that year, Thom completed his poem "Misanthropos," having submitted drafts for comment to Tony Tanner and Tony White, his close friends and trusted literary advisors. In 1965 Thom sent the finished poem to Encounter for publication. Stephen, constantly traveling, was seldom in the office. Thom's manuscript sat on Stephen's desk for months. I had read the poem, thought it was brilliant and significant, and kept moving it to the top of the pile to no avail. Finally I confronted Stephen about it on one of his rare appearances and asked him how he would feel if he had been the editor who rejected Eliot's The Wasteland? It was easy to make Stephen feel guilty—he had much to feel guilty about—and this worked. The poem appeared in the next issue of Encounter.

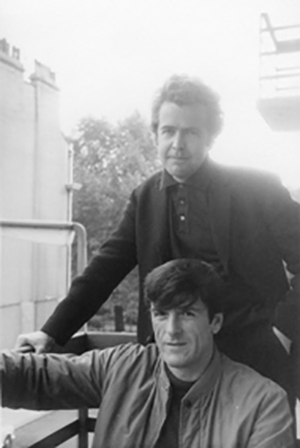

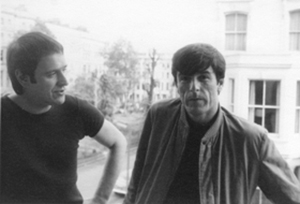

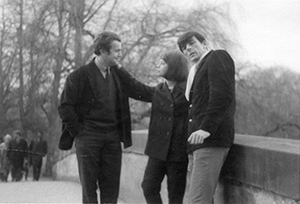

These photographs are from that period and were taken either on the balcony of Thom's London flat on Talbot Road or at King's College. The first shows Tony Tanner (TT) in his University gown with me (then Marcia Albright) and Thom at King's on the day TT was awarded his PhD degree from Cambridge. It was made by Shawn Gordon, an Englishman who had introduced Tony to me in Berkeley. Back in England, Shawn became a successful commercial photographer and one of our dearest friends. The next three show Tony Tanner, Tony White, Thom Gunn, and myself, each taking snapshots of the other three in turn, on a cold winter's day at King's. I'm in my charcoal gray flannel pants suit, one of the first worn in London. As is obvious, I was happy to be in the company of these extraordinary men.

Tony White (TW) is with Thom in the first of the seven Talbot Road images. TW was a complicated person: mysterious, paradoxical, charismatic and engaging, of ambiguous sexuality. He and Thom became close friends and soul mates as undergraduates at Cambridge, a bond that continued until TW's premature death in 1976. TT and TW became friends through Thom and I was ultimately included—if provisionally, as a woman—in this coterie.

TW studied literature at Cambridge, was attracted to the Existentialists (as was Thom), and with his thrilling deep baritone voice and arresting presence had been a promising young actor. He was being groomed by the Young Vic as "the next Richard Burton," when he defected from the theater entirely. The scion of an upper middle class family, raised to rule a dwindling empire, TW opted out of all that and earned his living as a construction worker and translator of contemporary French literature. (His mother was French, and he was bilingual.) It amused him that his graceful translations of Colette's fiction were attributed to the novelist Antonia White; he never tried to correct this error.

I'd met Tony Tanner in 1960 in Berkeley where I was an undergraduate English major at UC and he was a few weeks shy of finishing two years postgraduate work in American fiction on a Harkness Scholarship. We were both instantly smitten and spent his final days in Berkeley in an intense whirlwind of exhilaration and dread, the excitement of getting to know each other mitigated yet made more urgent by our impending, inevitable goodbye. Tony wanted me to know all the friends he'd made during his Berkeley stay, who ranged from academic literary scholars to beatniks (it was the beatnik era), jazz musicians, journalists, and poets like John Berryman, who was visiting the campus then. We spent a lot of time in bars during these long rituals of leave-taking.

The friend Tony revered most was Thom Gunn, whom he'd met not in England but in California. As if I weren't intimidated enough already by the prospect of meeting this famous English poet, Tony spent considerable time preparing me by feeding me far too much information. By the time I sat down for coffee with Thom and Tony in the squalid faculty cafe in Dwinelle Hall, I was all but paralyzed with anxiety and awe.

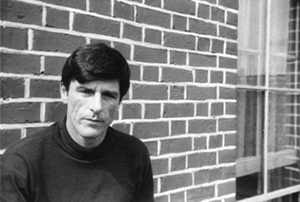

Thom was handsome and impressive-looking in that weathered way of his, with thick black hair, dark eyes and bushy eyebrows, an assertive nose, and deep vertical lines incising his cheeks. I liked his voice, pleasantly nasal and hesitant. He surprised me by acting as awkward as I felt. I remember him giggling and making silly remarks, like a young adolescent. It seemed ridiculous to ask him about his poetry under the circumstances, so I didn't. I was tongue-tied.

Knowing Thom was gay, I wondered if he felt uneasy around all women or just me, or was masking dismay that Tony actually had a girl friend. When we got up to leave, Thom tossed his key chain, comb and change into the trash bin and started to pocket his used napkin. This was my turn to giggle, and Tony's. Thom's abashed response once he'd realized what he'd done—he had tried to appear so cool—and his ability to laugh at himself endeared him to me forever after that.