"Misanthropos"

History and Context

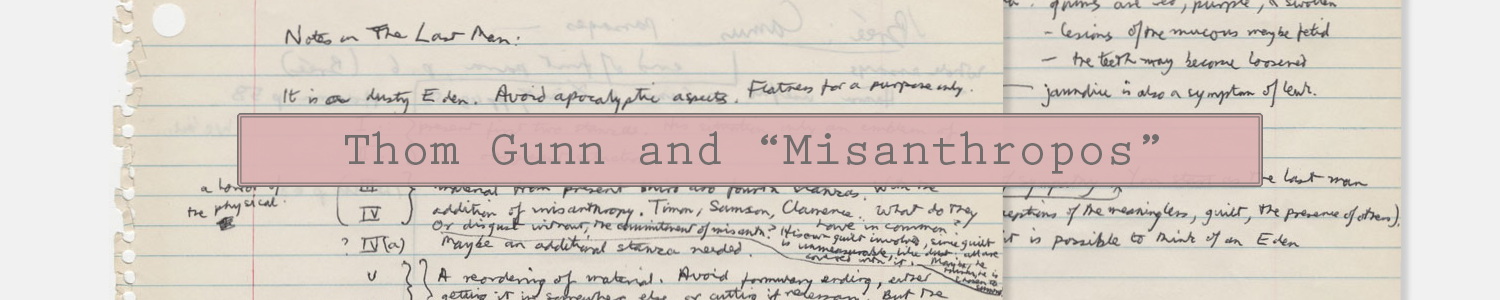

"Misanthropos," which critics have called Gunn's most ambitious poem, grew out of a work he began to draft in 1960 about the survivor of a global war. Originally a single short poem, Gunn realized it would have to extend into a long poem in order to fulfill his desire to express "a complete attitude to experience" (At the Barriers, p. 106). The poem was initially titled "For the Survivor." Other titles Gunn considered were "In the City of Kites and Crows" and "From the Green Tower." Although Gunn began work on the poem while he was residing in San Francisco, he completed it while he was in London from mid-1964 until mid-1965. It was first published in the August 1965 issue of Encounter and subsequently appeared in Gunn's next collection of poems, Touch (1967).

"Misanthropos" consists of a series of seventeen linked poems divided into four sections: "The Last Man," "Memoirs of the World," "Elegy on the Dust," and "The First Man." Weiner describes "Misanthropos" as "the story of a man who has served as a courier in a global war; he has escaped battle, and, having journeyed to a distant part of the world, and, not having encountered any other people, thinks of himself as the sole survivor" (p. 111).

Most of the items in this exhibit are drawn from the Libraries' holdings of Gunn's notebooks. Weiner asserts that they "are not personal diaries, but working notebooks, in which he explores ideas, begins essays, speculates, questions himself, and reflects on poetry and its place in his life" (p. 302). These early-1960s notebooks provide insight into his thoughts and attitudes leading up to the publication of "Misanthropos." They reveal a "preoccupation" common to his entire oeuvre— "his perception that modern poetry had lost ground to the novel, and his attempt to restore to poetry some of the relevance he valued in the novel and modern drama" (p. 106). To accomplish that, Gunn realized "he would need a 'transatlantic movement' of mind," opening up his work, previously located "within an English tradition of poetry," "to an American tradition, to nonconformism and more unpredictability" (p. 109). "Misanthropos" is "transatlantic" because it incorporates "more open 'American' rhythmic form, a meter loosened from a traditional accentual-syllabics." It also synthesizes "narrative and lyric form, to increase the capacity of lyric," opening the "lyric to include new rhythms and new verbal experiences" (p. 119).

Weiner concludes: "'Misanthropos' is a poem [Gunn] never stopped criticizing, so never stopped thinking about; it was a touchstone, a reminder; a spring chapter in the story of his effort to renew poetry after the formal and ethical exhaustion of modernism. It's not just the story of a poet, though, but of a man who wanted to live the one life given to him. The poetry is not the life, never can be; yet the reader does find a life in it, that is both more and less than the life the poet lived" (p. 126).