The Recording Ban of 1942

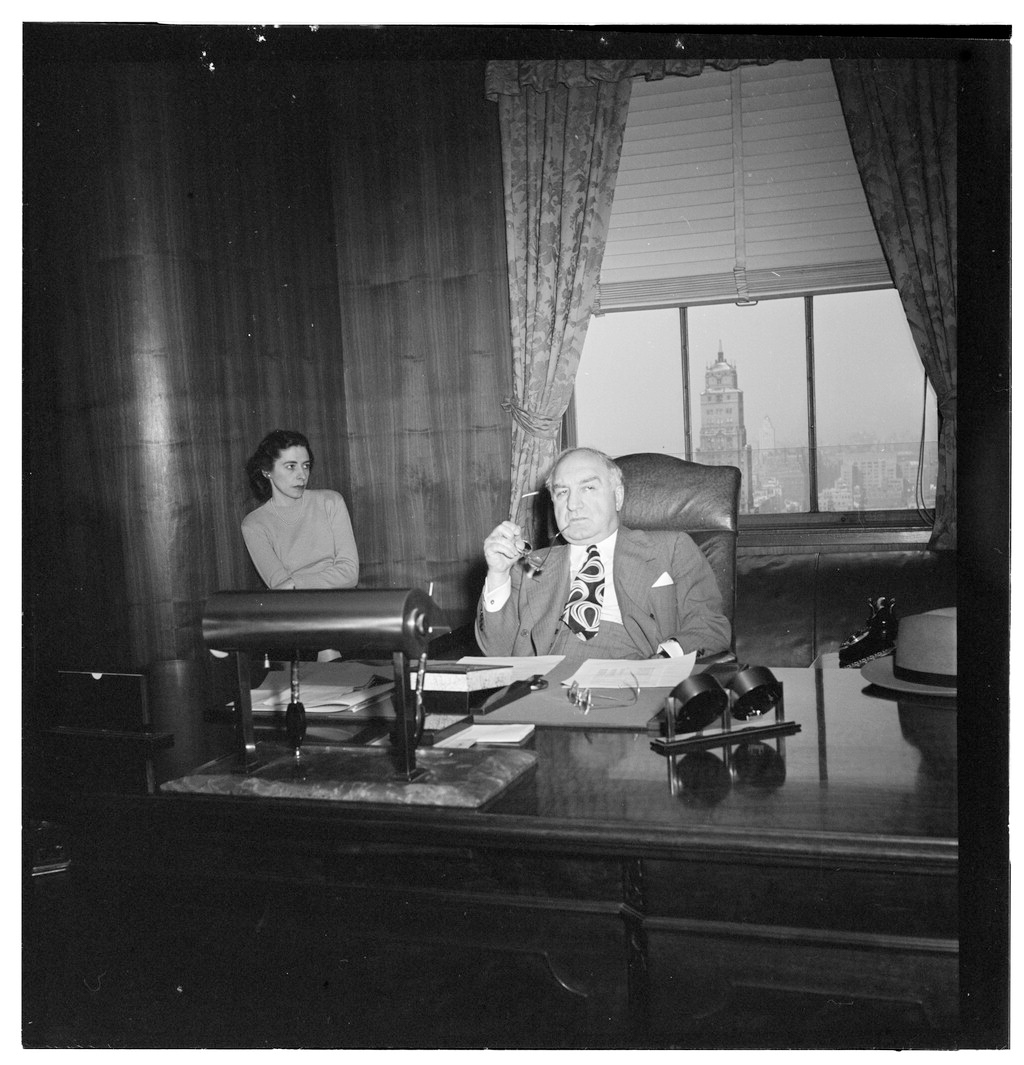

James Petrillo in his office, 1947 by William P. Gottlieb

Spanning the heart of the Second World War from August 1st, 1942 to November 11th, of 1944 the strike and its constituent recording ban greatly shaped the musical landscape of Wartime America and the history of popular music to come. The strike was organized and instituted by the American Federation of Musicians (AFM), the largest union in the world representing professional musicians. The main issue at stake in the strike was the payment of royalties on recorded performances, and because a settlement could not be reached, James Petrillo, president of the AFM (pictured above), instituted a total ban on AFM members participating in any recording session for commercial sale. Recording companies feverishly stockpiled recordings in the weeks leading up to the ban, and combed through back-catalogs for potential hits.

By 1943, then-smaller record labels such as Capitol and Decca had reached settlements with the AFM but RCA Victor and Columbia continued to hold out. The back-and forth grew so contentious that the case went before the National Labor Relations Board and moved President Franklin D. Roosevelt to write the AFM pleading "what you regard as your loss will be your country's gain."

The strike had innumerable effects. The AFM-admissable "V-Records" became notable tastemakers as these recordings were distributed extensively to troops oversees. Since the ban only pertained to commercial recordings, a great number of musicians devoted more time to radio, cementing the importance of the medium. Conversely, many musicians could not find work and indeed smaller-format groups prevailed in post-war years with the decline of big-bands and the rise of vocalists and small jazz combos.

Gottlieb, William P. "Portrait of James Petrillo in his office, New York, N.Y., ca. Feb." 1947. Monographic. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress.