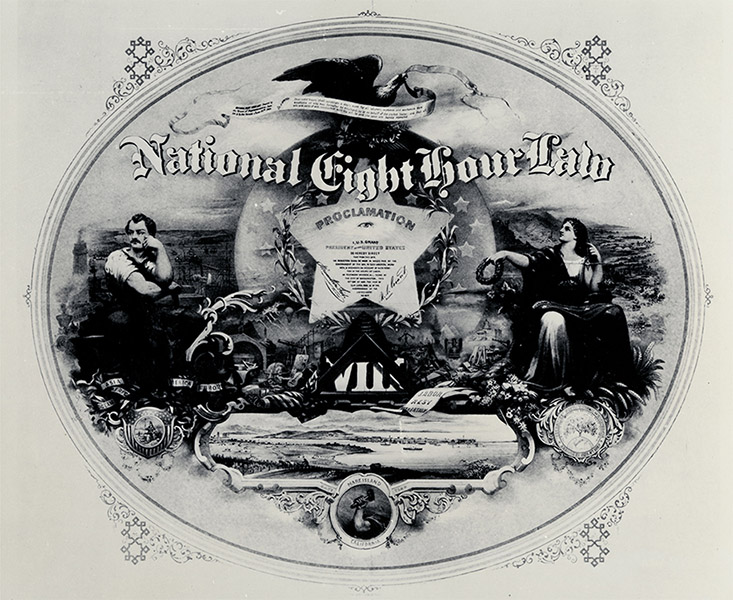

The Eight-Hour Day

Labor, Recreation, and Rest: The Movement for the Eight-Hour Day

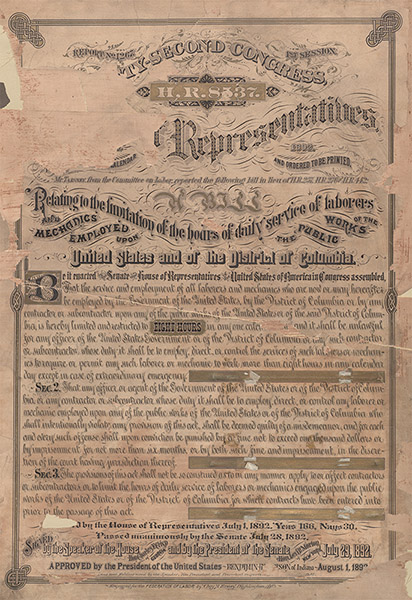

In the wake of the American Revolution, Philadelphia carpenters organized the first strike for a shorter, ten-hour workday. This strike began the American working class’ long struggle to reduce their work hours from the twelve-hour agricultural norm of sun up to sun down. In 1835, the Philadelphia carpenters again led another movement for a shorter workday by organizing America’s first city-wide general strike.

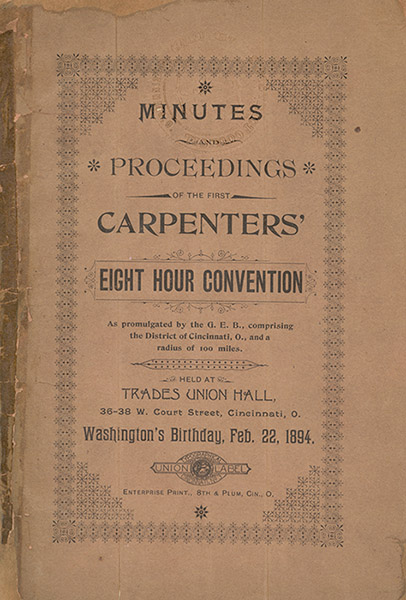

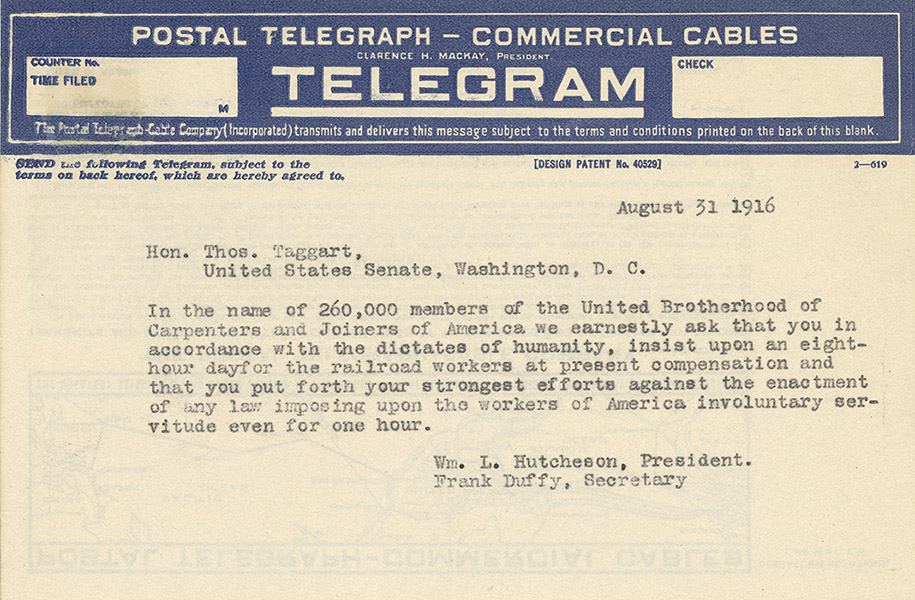

Over a half-century later, on May 1, 1886, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions called for a national strike demanding an eight-hour workday. Organized workers around the country answered the call. One resulting protest, at Haymarket Square in Chicago, led to a large police intervention and deaths on both sides. The backlash from the Haymarket affair set the movement for a shorter workday back for decades.

With the Great Depression’s severe unemployment, the labor movement revived the idea of reducing work hours and pushed for passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act, establishing an eight-hour day and forty-hour week. In the following decades, the labor movement worked to extend coverage of the law to all workers and prevent employers from forcing employees to engage in unpaid work.