U.S. Concert Bands in Context

By Christina Taylor Gibson

In the summer of 1965, during the Washington, D.C. American Bandmasters Association (ABA) meeting, composer and radio personality Don Gillis undertook a series of interviews with outstanding members of the organization, including founding member and circus march composer Karl King, University of Michigan band director William D. Revelli, and art music composer Vaclav Nelhybel. The interviews offer a window into concert band culture in the U.S. during the Cold War. Within the ABA, this period was embodied by a distinct turn away from professional bands that played popular music toward one centered on bands within educational institutions that aspired to art music status. This essay examines these specific concerns alongside larger cultural trends alluded to in these interviews such as national political imperatives like cultural diplomacy and space exploration, technology in the dissemination of music, and pervasive assumptions about women in professional life.

As Karl King alludes to in his interview, the ABA was formed to support and honor the professional bandmaster and his organization. Early members of the ABA were the leaders of the very best of these bands—Edwin Franko Goldman, Frank Simon, Arthur Pryor, Charles O’Neill, Karl L. King. That generation of bandmasters followed the model set forth by Patrick S. Gilmore and John Philip Sousa. The visual aesthetic tended toward the militaristic, with elaborate uniforms and patriotic musical numbers even for civilian bands performing at the circus or the minstrel show. Anxious to attract and retain an audience, the professional band tended toward musical conservatism. The repertoire included the ever-popular march, as well as transcriptions from well-known classical works. As in the symphony orchestra and the opera house of the era, there was with a special emphasis on late 19th-century material by composers like Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss. Although drawn from art music repertoire certain passages became nearly akin to popular music in their cultural ubiquity.

Despite the early membership of the ABA, the close of World War I marked the denouement of the professional band. By 1930, when the ABA first organized, the smaller professional bands began to disappear. Along with the professional band, the town band was also becoming a thing of the past. The large public bands that remained were buoyed by the star-power of their leaders and, as those bandmasters retired or passed away, the organizations crumbled. Tastes had moved toward other sorts of entertainment—big band jazz, for example—and were satisfied through radio performances and recordings as often as live performances at the local bandstand.

Nonetheless, band culture flourished by migrating into the burgeoning school system, which was responding to the increasing democratization of education. Such tendencies were already in process between the wars, but they became undeniable by the post-WWII era, as veterans relied on the GI bill to attend University while their children took advantage of well-funded suburban schools. The concert band and marching band became integral parts of this new educational system. Students learned to read music in Jr. High School, competed for division honors in High School, and served as public ambassadors through performance in University.

John Phillip Sousa, Hands Across the Sea, John Heney Papers, Special Collections in Performing Arts, UMD

Repertoire and performance practice responded to the increased alignment with the education system. The repertoire increasingly moved toward an integration of art music with more popular, crowd-pleasing music. Mid-century band culture was supported in this endeavor with compositions written especially for band. At first, such compositions tended to be in the British folk music tradition (Gustav Holst and Ralph Vaughan Williams), but soon Percy Grainger and Robert Russell Bennett also turned toward the band ensemble. In this environment band arrangements of Ferde Grofé's Grand Canyon Suite were very popular. Although the piece was originally composed for orchestra, many bands performed an arrangement of “On the Trail” by David Bennett. By 1935, Grofé had joined the ABA and was writing many compositions for band, including the Suite Hawaii presented on the second Sousa memorial program of the 1965 conference. As Grofé explained to Gillis, writing for band afforded opportunities for experimentation in front of an eager, enthusiastic audience, allowing, for example to depict the image of a volcano erupting with the use of whole-tones:

So I started very, well, almost, well, a very slow tempo, one note for each bar, one note. So that sort of tells the story and, after my way of thinking, of the sort of dormant lava of the subterranean depths . . . And as it slowly rises the band starts in a low key and it rises up just at the same way the volcano would begin to, would begin to erupt. And it rises higher and higher and higher and higher! And it finally spouts out! And that’s when I begin to have my fun! (edited for clarity)

Vaclav Nelhybel, Slavic March, ABA score collection, Special Collections in Performing Arts, UMD

Grofé's sense of adventurousness was surely emboldened by the broad, wide-ranging aesthetic of mid-century concert band programs. The first of the Sousa memorial programs presented during the 1965 meeting epitomized this approach. It included an arrangement of the national anthem by Edwin Franko Goldman and a Sousa march alongside Aram Khachaturian’s “Gallop” from Masquerade Suite, Emmanuel Chabrier’s “España Rhapsody”, Gustav Holst’s “Jupiter”, Paul Yoder’s “Arkansamba”, and the newly composed “Trittico” by Vaclav Nelhybel. The breadth of repertoire reflects the range of interests of the membership of the ABA of this era. Hubert Henderson was the conference host; correspondence in his collection reveals that featured conductors worked with the planning committee to choose which pieces to present. Naturally Lucien Cailliet, known for his arrangements of classical work and his association with Leopold Stokowski (a practitioner of dramatic, post 19th century conducting style), chose the Chabrier. Similarly, Major Arnald Gabriel of the U.S. Air Force Band conducted the national anthem. William D. Revelli, who was director of bands for the University of Michigan, chose Vaclav Nelhybel’s "Trittico". This too was a declaration of style and an acknowledgement of the ABA’s ambitions. Although Revelli’s marching band was known for its incredible stagecraft, in his interview with Gillis, the conductor focused on repertoire and the future of band repertoire:

…current interest among the great composers in the band is continuing to increase and I would predict that now in the not-too-distant future, that you will hear a great many of our concert and symphony bands playing music by the greatest of composers and music which is not geared actually to the entertainment, but to the aesthetic and cultural development of our people. The band, as you know, for many years was looked upon as an entertaining medium. I think today it is looked upon as a cultural medium of expression in music.

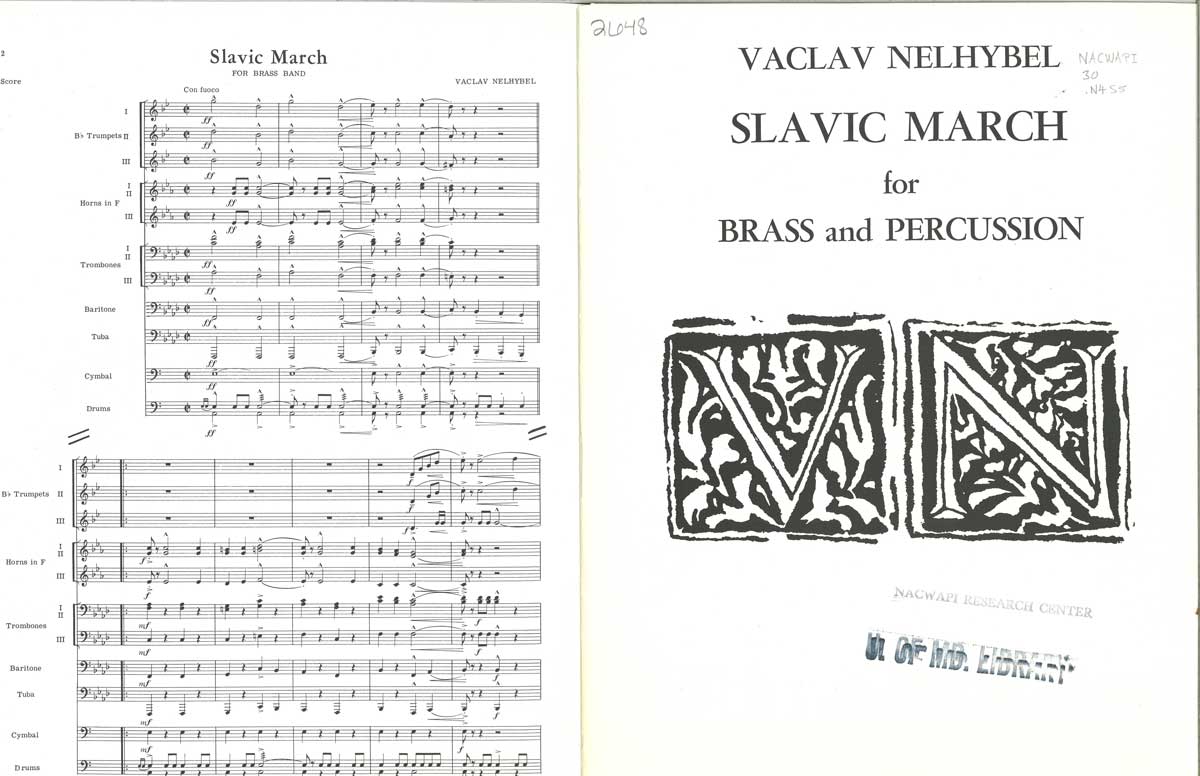

Lieutenant Colonel Curry Conducting U.S. Army Band, Gilbert H. Mitchell Collection, Special Collections in Performing Arts, UMD

The interest of composers like Paul Hindemith in writing for band was a point of pride among most of the interviewees. Lt. Col. Hugh Curry (former conductor, U.S. Army Band, Ft. Meyer), described his role conducting the premiere of Hindemith’s Symphony in B-Flat for Band as the “greatest single experience” of his career, and relayed with some pride his participation in commissioning the work and communicating with the composer about it. Similarly, as Nelhybel describes in his interview, Revelli courted and encouraged the composer’s work for band, allowing him to come to Michigan for a read-through of his first score and subsequently commissioning Trittico. But, as Nelhybel realized, although he might gain a few performances from his association with Revelli, there were many opportunities to write for Jr. High School and High School students. For that reason, Nelhybel explained to Gillis, he had spent the last several years working with students, guest conducting on their programs or running contests. Still, it is clear that Nelhybel’s aim is to write challenging art music for the best of these performers to aspire to play. Grofé's sense of expansive possibility with band repertoire was reflected by many of the interviewees, especially those conducting and writing music for students and educational institutions. Karl Holvik commented that,“ …in the short time that I’ve been in this business, we’ve seen a magnificent growth of repertory, technical facility, musical facility on the part of our students, and beautiful instruments which they have to play, and marvelous music, which is now available for band.”

As one might expect, the market for method books and “grade-one” compositions exploded, enlarging the types of available music. Some interviewees, like Arthur Brandenburg and Paul Yoder, shaped their careers specifically around the youth market. As Yoder explains,

Every band has to start. They don’t all reach the peak of perfection. And all of our students don’t stay with it. But they all start. And they all have that wonderful enthusiasm that you find in the junior high school, and that’s such a wonderful place to approach these students with new music and with something that they can perform, something that will appeal to them and still something that you hope has a high enough standard to keep raising their ideals in music a way as they go along.

Yoder’s career was founded on this idea: the broadest possible market is in the beginning band level and, should the composer be able to write well for that audience, he is assured a steady living. Indeed, the Yoder piece included on the 1965 ABA program was Arkansamba, which was also included in Rubank’s Elementary Method for Drum. The attitude and aesthetic typifies Yoder’s approach. It is slightly exotic and humorous, combining concepts like “samba” and “Arkansas” ordinarily thought to be distinct; it is challenging rhythmically, but not beyond the reach of a disciplined high school band; and therefore it is appealing to students and their parents alike. On the ABA program, the work was conducted by R.B. Watson, the director of the Pine Bluff High School Band from Pine Bluff, Arkansas.

Paul Yoder, Relax!, International Clarinet Association Score Collection, Special Collections in Performing Arts, UMD

The change from professional bands to school bands had not been painless. It required the creation of new infrastructure, including the publication of method books and the foundation of competitions or contests in order to satisfy parents of the worth of this educational endeavor. Several of the interviewees spoke at length about this process. Arthur Brandenburg, director of municipal bands in Elizabeth, New Jersey, and the publisher of several Rubank method books, notes the importance of the competitions in generating interest in school or recreational bands, "I would throw a great emphasis on the competitive field though, and I mean this in the proper light, to the extent that when students, both in solo and ensemble contests, and in the regular, larger groups, when they would go to contests, competitive festivals, if you please, and be evaluated by outstanding musicians, I think the band directors then had the support of the professional man who could come in and say the same thing to the students and the students would make remarkable progress." Similarly, Revelli remembered preparing for and winning contests as a key element of his success in creating a new band program in Hobart, Indiana:

Revelli and Brandenburg All-State Band Competition, 1949, Arthur Brandenburg Papers, Special Collections in Performing Arts, UMD

The first one was held in Fostoria, and perhaps the Joliet band was there, but I recall very vividly it being held in Joliet in 1927, and Mr. [A.R.] McAllister was, of course, a pioneer in this field. I think that the line, tracing it in the way it developed, Mr. [Albert Austin] Harding of Illinois held the first band clinic in the United States, and Mr. McAllister more or less copied his program from the Illinois program. So you see there was an evolution here. And then later on, there was a contest movement developed all over the United States. In fact, the prize winners of each state assembled to the national band site. My first experience in the national band contest was in Denver, Colorado, 1929 where we participated, and then each year it grew larger and bands would be in this locale, in this site of the contest for five days. You do a preliminary performance, and then they would select the five best bands to play it off as they do in the finals of a sports event and this would be held on the final evening in the, in the session, and believe me it was a real inspiring, marvelous experience for these children.

Most of the interviewees were, like Brandenburg and Revelli, active participants in the new band culture described above, and expressed enthusiasm about the present and optimism about the future. Karl King had a different point of view. He had made his career as a professional bandsman and was presently running a town community band in the old style. As a result, King expressed both regret and foreboding in his interview:

When I started in the business, you know, was in the old days of the town band and the municipal band and there were no school bands at all, there just was no such animal, and there were no university and college bands that I was conscious of except here and there out of some college a small band with twenty--twenty-five pieces like you’d call a pep band now, that’d play a little at a game or something, but there were no educational bands. The town band was king when I started. Each community had one. But this whole thing has changed, you know, the school bands, God bless ‘em, they help run some of the town bands out of business, that’s the only thing I have against them, but some of the smaller communities didn’t see fit to keep both of them going and, I think the old town band was really a part of Americana that should never have been allowed to vanish.

John Paynter, director of bands at Northwestern University enjoyed the educational environment of the university, but worried about the musical future of band members who would not go on to professional careers. Like King, he advocated for the return to something like a “town band”, now reformatted as “community bands” for city and suburban dwellers. He advertised his own efforts in this area, “I have experimented some in my own area there around Chicago with a community band and. . . [it has been] one of the most exciting experiences that I have had to make music with adults who have no incentive for playing other than the love music and the joy of playing good music.” Paynter’s idea was prescient. Over the ensuing decades, the community band movement did grow. Within a few decades most metropolises contained at least one such organization. The repertoire, however, never did return to the marches and transcriptions of King’s youth. It remains a mixture of genres, including original compositions and transcriptions, and, apart from sports games and parades, it has stayed in the concert hall and out of the town square.

The marching bands of the Civil War era were usually gendered masculine, but as the professional band grew in popularity at the end of the 19th century, women musicians became increasingly interested in the ensemble and its repertoire. They often formed bands of their own, such as the Ladies’ Cornet Band of Ashland, Oregon; the Lady Hussars of Watsonville, California; or the Butler Girls’ Band of Butler, Indiana. Well into the 20th century, a mixed gender band was unthinkable. After WWI, as the school band movement began to accelerate, most towns invested in boys-only bands or in separate boys and girls bands, but when WWII encouraged young men to turn their attention away from music and toward war, bands quickly became gender-inclusive for practical reasons. In his interview Brandenburg describes the phenomena, as it affected the Elizabeth, New Jersey Bands:

This particular city saw fit to have an all-boys high school, which opened in 1929.The city had an academic high school formerly co-ed in which there were just six girls, but on the opening of the new school, the principal of the girls’ school said, “we must have a girls band”. I shuddered at the thought because there’d been no experience of this type at all . . .

Early Co-ed Band, undated, Arthur Brandenburg Papers, Special Collections in Performing Arts, UMD

Early Co-ed Band, undated, Arthur Brandenburg Papers, Special Collections in Performing Arts, UMD

In 1944, when the second World War broke out, naturally the boys high school felt the extreme effects of alumni and so on, going off to service. . . . So we cleared it with the school authorities, merely put an announcement in the paper and we had forty-five people report with instruments at the first rehearsal. Quite complete as far as instrumentation was concerned, except for the instruments that we borrowed from the school rehearsal facilities. At the second rehearsal, fifty-five people reported, largely young ladies because the men were in service.

After WWII, many school and community bands retained a coeducational structure, and, as school band programs exploded in size, women also supported the programs through fund-raising booster activities. Revelli acknowledges the parental role when he recounts a reunion with students from his early career as a school bandmaster in Hobart, Indiana: “In fact, thirty years later, this was one of the joys of returning to Hobart the other night, these mothers are just as active today. In fact, it’s their children who are now the band mothers. And they raised sufficient funds to buy our instruments, our uniforms, our library. They paid for all of the trips to visit the district, the state, and the national contests, and it was a marvelous experience.”

Within the ABA, women also played a crucial supportive role. Although no women were yet accepted as bandmasters, the wives of the bandmasters formed their own auxiliary, the “Band-Aids” in 1954 (motto: “we stick”). The women organized their own social activities as well as helping to organize the conference. Several members of the mid-1960s “Band-Aids” were professional musicians, including Gladys Wright (band director), Elizabeth Verran (piano teacher), Edith Swartley (cellist), Virginia Sperry (piano teacher), Margaret Shepard (music administrator), Eleanor Meuser (pianist), Peggy Kerr (vocalist), Cordonna Graham (organist), Beryl Falcone (music teacher), Jessie Buchtel (violinist, violist), and Margaret Bowles (organist).

Don Gillis concluded almost every interview by asking the interviewee to predict the future of bands in the U.S. The answers to this question revealed some of the dominant hopes and fears of the day, with some wishing for a return to an earlier cultural norm and others radically optimistic about the future. Predictably, King was the most wistful of the respondents, asking to “come back a little ways towards more of a traditional band music and not quite so much of this wild type of thing.” In a similar vein, several interviewees expressed concern about the increasing emphasis on math and science during the space race. Brandenburg issued a cautionary wish to keep, “the arts as part of the entire educational system,” and Holvik advised, “All I would ask is that we don’t forget two things: we don’t forget that we play for people, and we don’t forget that we conduct people.”

But at the same time that the emphasis of educational and cultural institutions was shifting, the concert band community was experiencing an enormous expansion of art music repertoire composed especially for the band. It was this phenomena that prompted Curry’s unfettered optimism:

I think that the band will continue going upwards as it has, with finer performers, with finer music, especially music written especially for band. It has to. It wasn’t so many years ago that the school band movement was pretty much in the Mid-West and it has proliferated throughout the entire country now. I know my own bailiwick, New England, was primarily a vocal stronghold and now the high school band program is moving up there. And I think it’s moving all throughout the country, and there can be nothing, nothing at all but improvement and, as I said before, onward and upward.

In many ways, the predictions of both optimists and pessimists have been confirmed by more recent trends. Concert band music has continued to be varied, attracting folkloric and avant-garde composers alike, as seen by the recent Sousa-Ostwald award-winning compositions. Half a century later, public school bands continue to provide first exposure to music for thousands of school children each year. Nonetheless, funding for arts programs has faltered since the mid-20th century, stretched anew with each budget cut, and out-of-reach for poorer school districts. Meanwhile despite the growth of community bands, the town band has not revived to supplant faltering school programs, leaving many children without meaningful instrumental instruction during their formative years.

These histories serve as reminders of roads traveled and others we might anticipate. Certain themes seem dated by contemporary standards, such as the expressions of anxiety about women in instrumental ensembles or the nostalgia for the town band. Other ideas still resonate, like those about balance math and science with arts and humanities educational institutions, or the pursuit of new repertoire for the band. Most of all, the interviews give insight into the variance of human navigational strategies during times of professional transition.

All quotations edited for clarity.