From Friends to Foes

The Late 19th Century to 1941

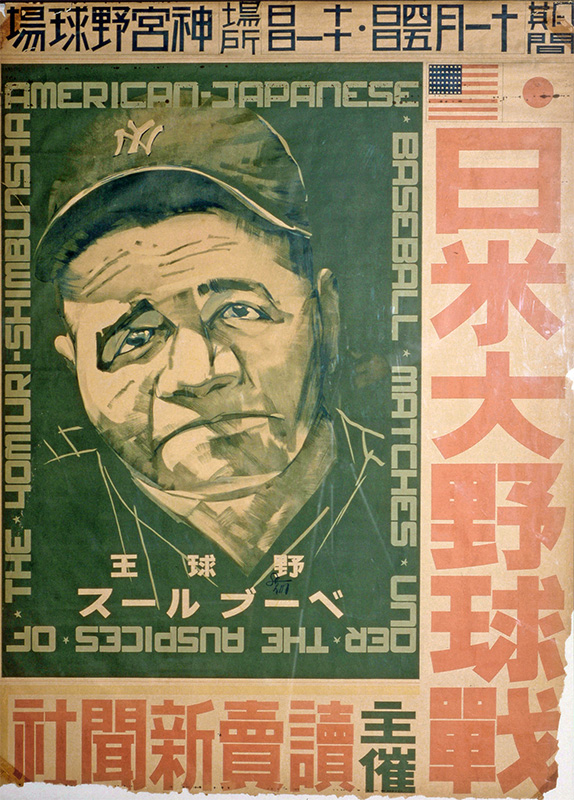

Poster for the 1934 All American Tour in Japan, Courtesy of the Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Japan

Relations between the Japan and the U.S. began in 1854, when American gunboats forced Japan to open its ports to trade. Following the Meiji Restoration of 1868, the country embarked on a vigorous program of modernization. The Japanese saw the West as the epitome of a modern society and adopted many elements of American technology, institutions, and culture. A variety of cultural exchanges strengthened ties between the two countries in the early twentieth century, including highly popular visits from sports celebrities. As Joseph Grew, U.S. Ambassador to Japan, remarked on November 6, 1934, "Babe Ruth...is a great deal more effective Ambassador than I could ever be." (Banzai Babe Ruth: Baseball, Espionage, & Assassination during the 1934 Tour of Japan, 2012)

Babe Ruth during the 1934 All American Tour in Japan, Courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, United States

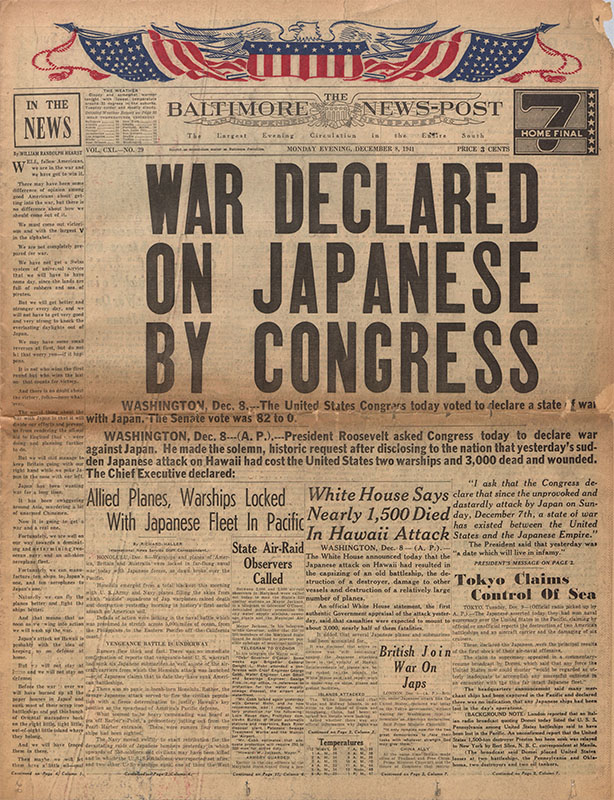

Warring Parties

Pearl Harbor Attack, December 7, 1941

Japan’s invasion of parts of China and Indochina threatened U.S. interests in the Pacific, generating political and financial conflicts between the two nations. The worsening relationship climaxed when the Imperial Japanese Navy bombed American bases at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941, after the U.S. embargo on oil to Japan. The U.S. declared war on Japan the next day.

The U.S. Naval Base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii in flames, 1941, National Archives and Records Administration

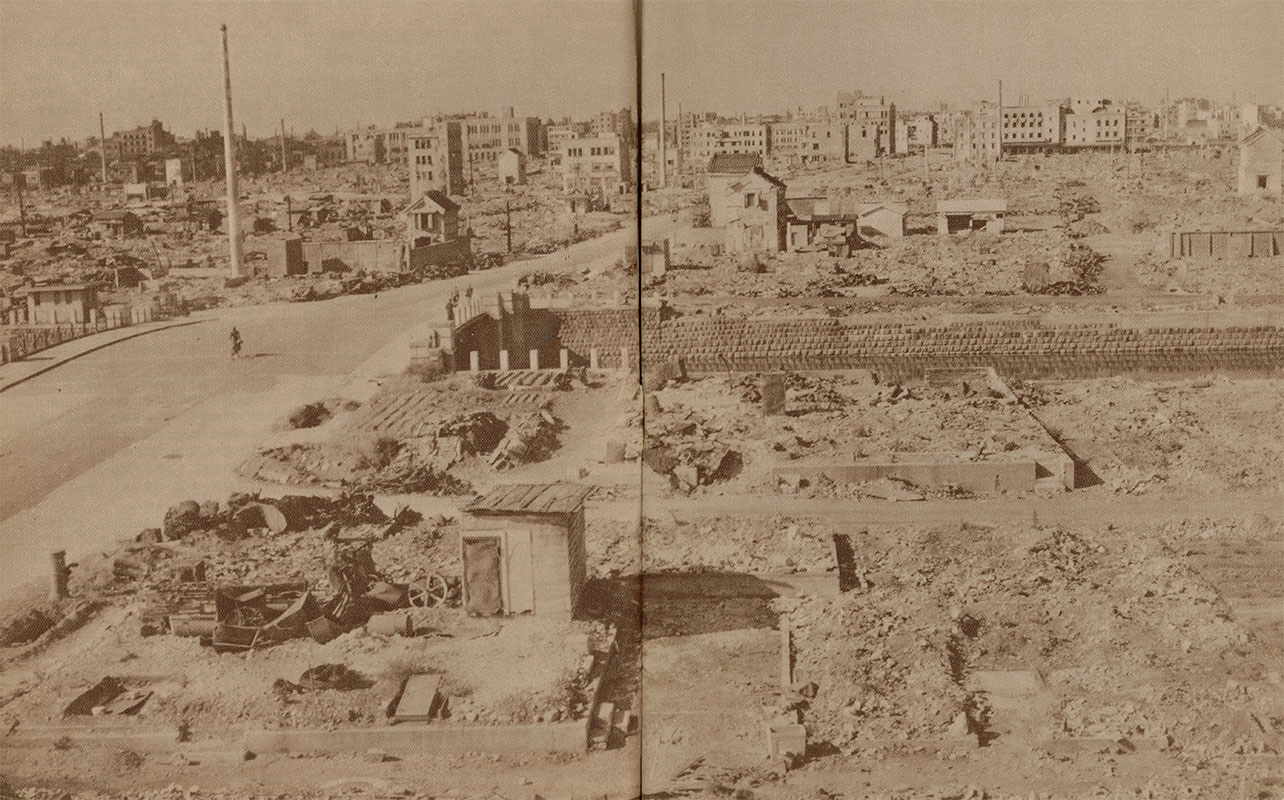

1945

Devastation

During the spring and summer of 1945, American firebombs devastated Tokyo and 66 other Japanese cities. Then on August 6 and 9, the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s unconditional surrender to the Allied Powers one week later. In his four-minute radio address, he asked his physically and spiritually exhausted subjects to “endure the unendurable and bear the unbearable” by accepting defeat.

In the wake of Japan’s defeat, U.S. service members and their families flooded into Tokyo and built “Little America” enclaves that were off limits to unauthorized Japanese. Within these self-contained communities, they enjoyed an American middle-class lifestyle amidst the poverty of the war-torn city.

The Ningyo area of Tokyo from Kiyosu bridge in the fall of 1945, Tokyo Fall of 1945, 1946

And Hope

Recreating an American way of life in devastated Tokyo would not have been possible without Japanese ingenuity and labor. Ordinary Japanese were employed in a variety of ways to satisfy the daily needs of American families. Japanese employees were enthusiastically involved in the enterprise as they translated their hopes for a new Japan into their interactions with the American occupiers.

By recovering the voices of the Japanese in this moment of encounter, Crossing the Divide explores how Japanese people participated in building an American Dream for the occupying military personnel and how through this experience the Japanese began to rebuild their lives and construct a new nation.