Postcard Eras

Pioneer Post Cards (1861-1898)

"Pioneer" cards are post cards that were published before the May 19, 1898 Act of Congress, which allowed privately-printed cards to be mailed for the same one-cent postage as government-issued cards.

Lipman Card Era: 1861-1893

Government-Issued Postals: 1873-1893

The Precursors to View Cards

Pioneer View Card Era (1893-1898)

Source: Ryan, Picture Postcards in the United States. Pages: 1-14.

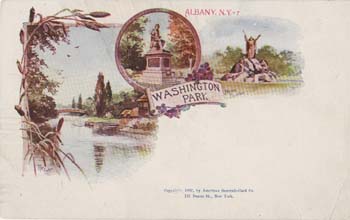

Although privately-issued postcards had been in circulation in the United States since 1861, and government issued cards since 1873, the first picture postcards in the U.S., known as viewcards, were sold and popularized in 1893 at the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois. Illustrations on small “postal” cards with room for a mailing address on the reverse were printed with a one-cent stamp by the U.S. postal service. Privately printed cards were sold as “souvenir cards” and required a two-cent stamp for postage. (Tips for determining when a U.S. postcard was published). “Official cards” were created even before the fair and were sold in vending machines at a cost of two for five cents. Pre-fair sales went well enough to create sets of ten and twelve souvenir cards for purchase during the Exposition (Burdick 22). The success of the postcard sales during the Columbian Exposition was well noted, provoking postcard publishers to print views featuring America’s attractions, including historic sites and resorts, meant to attract tourists and act as travel souvenirs (Burdick 15).

Washington Park, Albany, New York

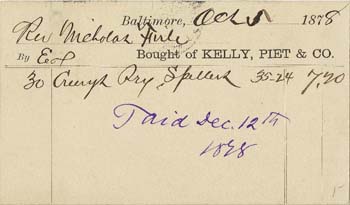

Kelly, Piet & Co. Receipt

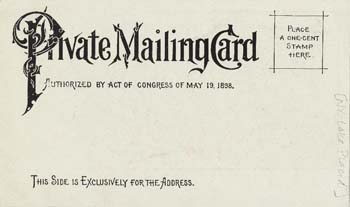

Private Mailing Card Era (1898-1901)

Bogdan and Weseloh, Real Photo Postcard Guide: The People’s Photography.

In 1898, Congress passed a bill that halved the cost of postage for commercially produced cards from two cents to the one cent required for government issued postals. In return, these non-government cards were required by law to be identified by the words, “Private Mailing Card, Authorized by an Act of Congress of May 19, 1898” printed on the back. This law allowed postcard publishing companies to more easily compete in the picture postcard market, causing many new publishers to enter the scene and subsequently, bringing postcard production to new heights (Burdick 16).

Wilmington Falls, Adirondacks, New York

Hotel Ausable Chasm, Victoria Falls, New York

Crow's Nest, Asbury Park, New Jersey

Hotel Ausable Chasm, Victoria Falls, New York

Private Mailing Card

Real Photo Postcards (1899-1920) and Cyanotypes (18__-?)

Bogdan and Weseloh, Real Photo Postcard Guide: The People’s Photography. Pp 8-9.

Real Photo Postcards, or RPPC’s, as they are commonly called, are true photographs, chemically produced on photographic paper from a negative, with a printed postcard back. 1899 was the first year that real photo postcards, as we know them, were produced. It was in this year that Velox, the first commercial photographic postcard stock, complete with photographic paper in the standard postcard size with a printed address back, was produced and sold (Bogdan and Weseloh, 16-17). A few years later, beginning in 1903, the Kodak model 3A folding camera was introduced. The camera utilized postcard-size negatives, thus allowing for even easier processing of the photographed images onto photographic postcard stock. Nevertheless, it took the popularity of the general postcard-collecting craze, especially apparent in 1906, to convince photographers to create real photo postcards in earnest.

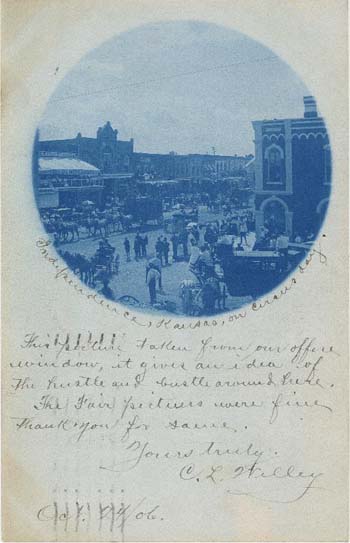

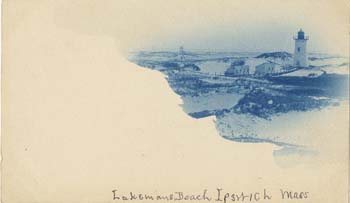

The earliest real photo postcards were created as cyanotypes. Cyanotype processes were popular among amateur photographers who produced an estimated 90% of these blue postcards. The ease of developing cyanotypes was the driving factor, with only sunlight required to develop the images, and no chemicals needed to stabilize them (Blake and Lasansky 19). The blue tones of the process work especially well on landscape views, though personal portraits were taken as well. Journals like Camera and Darkroom and American Amateur Photographer printed articles outlining for their readers techniques for creating photo postcards from their own negatives.

Professional photographers on the other hand, created postcards for profit and preferred to send their negatives to a high-speed, commercial printer for mass production of their photographic images onto sensitized postcard stock (Blake and Lasansky 19). While printed view cards were the postcard of choice in urban areas, local photographers would sell their photographic postcards to merchants in low-density areas. Many of these cards focused on rural landscapes and small town life, documenting a culture that might otherwise be forgotten. (Bogdan and Weseloh, Real Photo Postcard Guide: The People’s Photography. P.48)

Cyanotype Postcard

Lakemans Beach, Ipswich, Massachusetts

Long View Park, Rock Island, Illinois

South Jefferson, Maine

Coronado Hotel

Undivided Back Era (1901-1907)

Bogdan and Weseloh, Real Photo Postcard Guide: The People’s Photography.

In December of 1901, Order no. 1447 was issued by the U.S. Postal Service, allowing the formal “Private Mailing Card” title to be dropped from the back of commercially printed cards and replaced with the simple, “Post Card.” At this time, only the name and address of the postcard recipient were permitted to be written on the backs of postcards. The “Undivided Back Era” is so named in opposition to the subsequent “Divided Back Era,” illuminating the importance of the regulatory change that would designate more space for correspondence.

It is during this era that large postcard publishers, like the Detroit Publishing Company, The Rotograph Company, and Curt Teich established a name for themselves in the American postcard market. Mostly producing “viewcards,” or images of downtowns, civic buildings, and sites of historical importance, the publishers added photographers to their payrolls who were responsible for providing the company with images of their assigned geographic areas. Thousands of different view cards were printed by each firm. Areas that were not photographed by the major publishing companies looked to the local druggist, who would send photographs taken by local photographers to Germany for printing, where printing processes were inexpensive and of high quality. (Ryan, 145-6).

Yachting on the Pacific, Santa Cruz

Tall Buildings, Lower New York

Public Library and Reading Room, Bristol, Connecticut

Beach at Hough's Neck, Quincy, Massachusetts

St. John's Hospital, Joplin, Missouri

Concordville, York Beach, Maine

Divided Back Era (1907-1914)

A new law, passed March 1, 1907, allowed for the inclusion of correspondence on the back of post cards, separated from the address information by a vertical line. Now the postcard fronts could be used exclusively for the image, with no need for blank space (Bannister 14). This law helped bolster postcard sales, giving this already inexpensive and convenient method of correspondence more space to carry news, good tidings, or business notes. Postcard collecting during the Divided Back Era had become a national passion, and over half the cards sold at this time went straight into personal collections without even being mailed (Bannister 14). Although postcard collecting had become trendy, sending postcards was still popular, and eight times as many postcards as people in the United States went through the mail in 1908 (Bannister 14). Postcards hit their peak popularity at this time.

Postcard sales could not keep increasing much longer, and indeed 1909 marked the beginning of the decline. The Payne-Aldrich Act imposed a tariff on imported postcards during this year, which had the unintended effect of reducing the price of postcards. Because American postcard dealers anticipated the tariff, they had already acquired large quantities of higher-quality, foreign cards. The dealers discovered they could not afford to keep a large inventory of postcards on hand, so they sold them to consumers at a reduced cost. Many American postcard publishers went out of business as a result (Bannister 14).

Albertype postcards (1890-1952). [Ours are all date from 1907-1914.]

http://www.hsp.org/files/findingaidv18aalbertype.pdf

http://www.loc.gov/rr/business/BERA/issue2/wittemann.html

Made through a photomechanical process, Albertype postcards were essentially collotypes. Photographic negatives were used to create plates with an exact image of the photograph that was then used to make prints on a large scale. The Albertype Company of Brooklyn, New York was the first American company to take advantage of the new technology of collotypes, which was an inexpensive and effective way of making realistic images. Joseph Albert, discovered ways to improve the collotype printing system, allowing his work to earn the title of “albertype.” The company produced 25,000 collotype images over its sixty years in business, which were sold as postcards or printed in viewbooks. (http://www.hsp.org/files/findingaidv18aalbertype.pdf) Some of these postcard images were beautifully hand-colored, adding novelty to postcards valued by collectors.

Entrance to the Ormond

Wappello County Court House, Ottumwa, Iowa

High Street, Belfast, Maine

Divided Back postcard

Divided Back postcard

Divided Back postcard

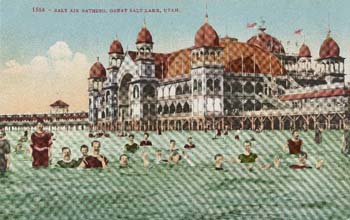

Salt Air Bathing, Great Salt Lake, Utah

Interior View Butterfield Museum, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire

White Border Era (1915-1930)

Postcard imports from Germany came to a halt during World War I, allowing American publishers to take advantage of the void in the market. American printers did not have the lithographic technology that Germany used, and as a result, the postcards of this era are of lower quality than the previous eras. The white borders that characterize these postcards were due to the cost-saving measures of the war effort. Postcard images were smaller, so less ink was utilized in the printing of the postcards, and less precise techniques for cutting large sheets of factory-produced postcards were required when the borders were used. (Bannister 15).

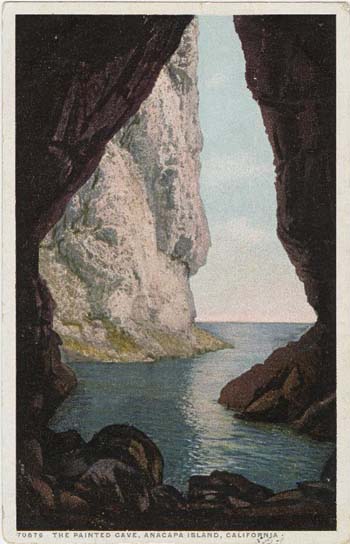

The Painted Cave, Anacapa Island, California

Australian Pines Ave, Palm Beach, Florida

Where the Fisherman Land, Miami, Florida

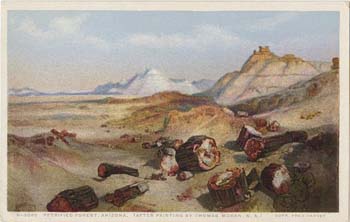

Petrified Forest, Arizona

Lee and Gordons Mills, Chickamauga, Georgia

Linen Era (1930-1944)

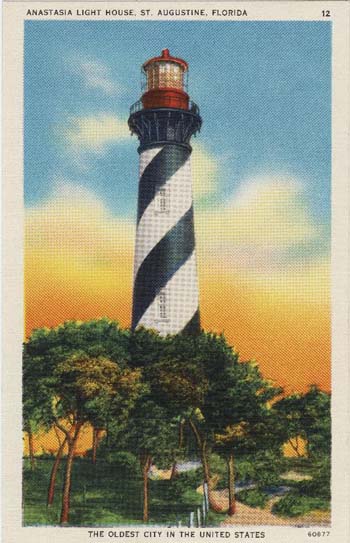

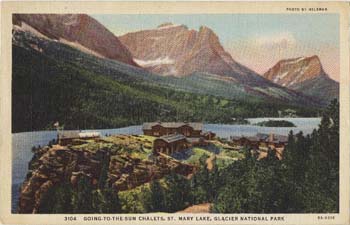

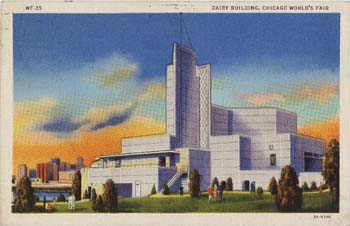

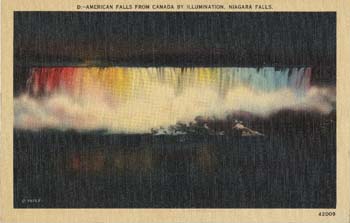

While some Linen Era postcards continue to use a white border, these cards are distinguished from their White Border Era predecessors by the high rag content used in the postcard stock. A woven, “linen-like” finish is very apparent in these cards, which are many times also characterized by the use of bright dyes and eye-catching color schemes. (A Brief Guide to Identifying… and Tips for Determining…).

Anastasia Light House, St. Augustine, Florida

Going-to-the-Sun Chalets, St. Mary Lake, Glacier National Park

Dairy Building, Chicago World's Fair

American Falls from Canada by Illumination, Niagara Falls

Hutchinson Court at the University of Chicago, Illinois

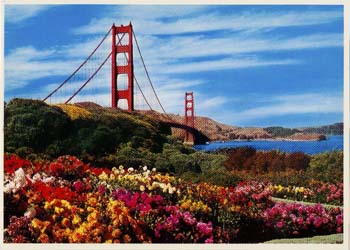

Photochrome or Chrome Era (1945-present)

The “chrome” era postcards are mostly the cards that are currently produced and sold. By utilizing a high-quality printing process that creates an image by staggering and mixing colored dots, photochromes are many times confused for real photographs, though early examples showed some blurred features.

A “Not so Concise History of the Evolution of Postcards in the United States.”

http://www.metropostcard.com/metropchistory.html

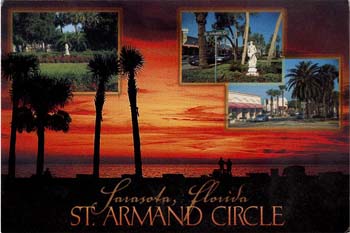

St. Armand Circle, Sarasota, Florida

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House

The Sunken Garden, The Butchart Gardens