A Voice Crying in the Wilderness: William Morris As Socialist

William Morris was deeply disturbed by the inequities and income disparities he observed in Victorian society. In 1883, he joined the Social Democratic Federation, the first official socialist party established in England. Like many in the movement, Morris struggled to define his vision amid the many competing views on the ideal organization of society. He advocated radical revolution and change through government reform at different times in his life.

With Eleanor Marx, the daughter of Karl Marx, and other prominent party members, Morris formed the breakaway Socialist League in 1884. Ultimately frustrated by ideological differences between anarchists and reformist party members and exhausted from his relentless schedule, he abandoned all organized political activity in the early 1890s.

Morris's enduring contribution to the cause of social equality was largely educational. He financed, edited, and wrote for the Socialist League's monthly publication, Commonweal, and was a popular speaker at party meetings and on street corners where he explained the merits of socialism. Even after resigning his Socialist League membership, Morris continued to champion socialist ideals in his writings and endeavors.

Morris agreed with fellow socialists who promoted social equality and yearned for a greater sense of communal fellowship. He was also an outspoken advocate for freedom of the press. Morris was not a politician, but an activist and agitator who brought intellectual weight and energy to the socialist cause. According to fellow party member Bruce Glasier, socialism was "integral to his genius; it was born and bred in his flesh and bone." Morris is remembered today as one of the most influential figures of England's nascent socialist movement.

Image: Header Image, Chants for Socialism, 1892.

"Nothing can argue me out of this feeling...the contrasts of rich and poor are unendurable and ought not to be endured by either rich or poor."

- William Morris, letter to C. E. Maurice, 1883 -

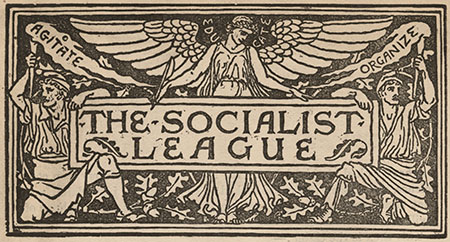

How I Became a Socialist

by William Morris

London: Twentieth Century Press, 1896

In How I Became a Socialist, Morris describes his vision of a socialist society: "... what I mean by Socialism is a condition of society ... in which all men would be living in equality of condition, and would manage their affairs unwastefully, and with the full consciousness that harm to one would mean harm to all-the realization at last of the meaning of the word COMMONWEALTH."

Manifesto of English Socialists

by William Morris

London: Twentieth Century Press, 1893

Manifesto of English Socialists provides a rare example of unity among disparate socialist parties. Co-written by Morris, Henry Hyndman, and George Bernard Shaw in 1893, this document states the ideals shared by members of the Socialist League, the Social Democratic Federation and the Fabian Society.

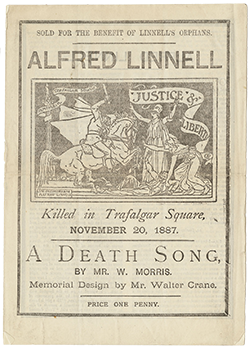

Alfred Linnell Killed in Trafalgar Square: A Death Song

Design by Walter Crane

William Morris wrote A Death Song in honor of Alfred Linnell, a radical writer who was trampled to death by a police horse during a protest in London's Trafalgar Square in November 1887. The protest, part of a series of demonstrations organized by the Democratic Federation, the Socialist League, and the Irish National League, aimed to call attention to poverty, restrictions on free speech, and English coercion in Ireland.

Chants for Socialists

London: The Socialist League, 1892

Morris was deeply affected by the police brutality he witnessed during the "Bloody Sunday" demonstrations. Attendants at Linnell's funeral - many of whom had attended the earlier demonstrations-sang Morris's "Death Song" as an act of defiance and solidarity. The text was reprinted in Chants for Socialists, a Socialist League publication.

True and False Society

by William Morris

London: Hammersmith Socialist Society, 1893

Morris spoke on street corners and in lecture halls to educate members of the public about Socialist causes.

Useful Work versus Useless Toil

by William Morris

London: Hammersmith Socialist Society, 1893

He often published his speeches as penny pamphlets affordable to working-class readers.

Many Hammersmith Socialist Society pamphlets featured an advertisement for weekly meetings held at the foot of Hammersmith Bridge. Morris also hosted Sunday morning lectures at his London home, Kelmscott House.

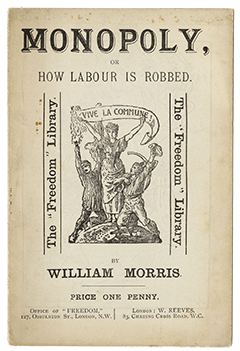

Monopoly, Or How Labor is Robbed

by William Morris

London: Office of "Freedom", [1891?]

Notable English illustrator Walter Crane created much of the artwork for Socialist League and Hammersmith Socialist Society pamphlets.

His political cartoon featured in Monopoly, Or How Labor is Robbed illustrates the social strife inherent in a capitalist system.

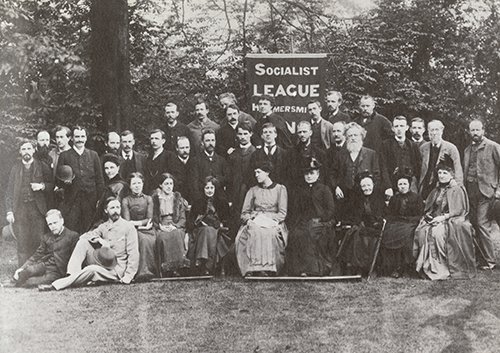

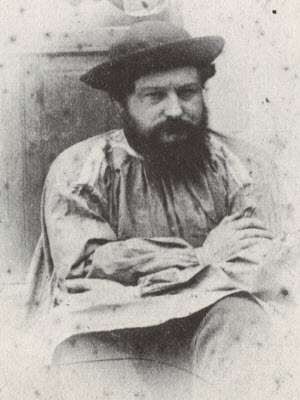

Hammersmith Branch of the Socialist League

Image

This photograph of the Hammersmith Branch of the Socialist League features Morris in the second row, fifth from the right. His daughters are seated in the front row, May second and Jenny fourth from the left.

A Dream of John Ball and King's Lesson.

by William Morris

London: Logmans, Green, 1903

Morris's literary works often incorporated socialist themes. A Dream of John Ball and King's Lesson extols the values of community, fellowship, and free labor through a narrative of a pre-industrial peasant rebellion.

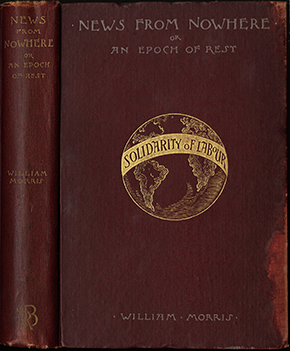

News from Nowhere

by William Morris

Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1890

In News from Nowhere, Morris envisions an idyllic socialist future for England. The narrator dreams of a 21st century Socialist utopia where private property is abolished, poverty disappears, and people find pleasure in everyday work. The design on the 1913 volume is taken from Walter Crane's 1889 International Solidarity of Labour illustration.

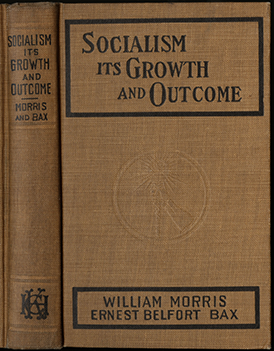

Socialism, its growth and outcome

by William Morris and Ernest Belfort Bax

Chicago: Charles H. Kerr, 1913

In addition to writing fiction, Morris kept a diary of his early involvement in the Democratic Federation and wrote commentaries on current events that were published in newspapers and journals. In collaboration with prominent intellectual Ernest Belfort Bax, Morris wrote Socialism, its growth and outcome, an analysis of socialism throughout history.

Art and Socialism

For William Morris, art and socialism were inextricably linked. Morris condemned capitalism for widening the gap between England's poor and wealthy in the nineteenth century, and also for diminishing the role of art in people's lives. Working-class laborers, given no control over what they produced, likewise had no control over the style of the items they made. Morris contrasted modern capitalist labor with labor in the middle ages. In his view, medieval workers possessed greater autonomy, including more freedom to express themselves as individuals through arts and crafts. In Morris's ideal world, true beauty was born from pleasurable work.

Every major artistic and literary endeavor by Morris was rooted in the belief that all people should have access to fulfilling work. Workers should be able to contribute their creativity and direct their physical labor. Morris tried, with only partial success, to translate his vision for a more egalitarian workplace into reality in his own workshops. Many of his Morris and Co. products were designed by artisan friends who were committed to handcrafted furnishings, though he also employed wage laborers in their production. At the Kelmscott Press, Morris and his colleagues excelled in such areas as typeface design and illustration. Numerous aspiring craftsmen applied Morris's labor model to their own work in the late nineteenth century, including members of the Art Workers' Guild, the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, and the Century Guild.

"What business have we with art unless all can share it?"

- William Morris, letter to Manchester Examiner, 1883 -

Architecture, Industry, and Wealth: Collected Papers

by William Morris

London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1902