The Tale Saith: Morris as Translator

William Morris began publishing translations of the Icelandic sagas in 1869. The sagas, composed after Iceland was settled by Norse immigrants in the 9th century, combine history with folklore. Just as Homer's Iliad and Odyssey provided ancient Greeks with mythical accounts of their forebears, the sagas provided Scandinavian people with dramatic stories of Iceland's first settlers. For Morris this mixture of history and mythology fit his vision of employing art to interpret and understand the past.

To create the translations Morris first recruited his friend Eirikr Magnusson to teach him the basics of Icelandic. Magnusson then translated the original prose tales into English, and Morris in turn rewrote the stories taking on the persona of a medieval troubadour. He crafted active and dramatic tales in poetic form.

In addition to the numerous Icelandic tales that Morris translated with Magnusson, Morris translated medieval French tales. His Kelmscott Press published three small format editions of these tales. Morris also produced translations of Homer's Odyssey, Virgil's Aeneid, and Beowulf. Critics panned Morris's classical translations and the Beowulf, but his goal was never to please the scholars. Translations, for Morris, were meant to capture the spirit of the original text without undue reliance on the actual words.

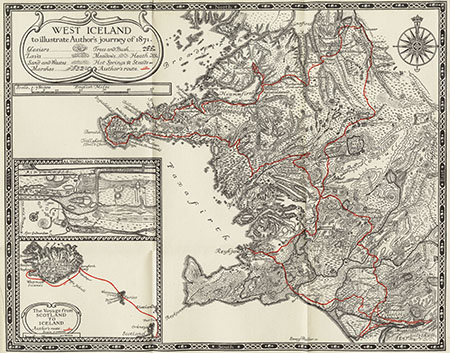

Image: Map of William Morris' 1871 journey through Iceland.

"I can't be bothered with grammar...I have no time for it...

I want the literature, I must have the story. I mean to amuse myself."- William Morris, in conversation with Eirikr Magnusson, c. 1869 -

Volsung Saga: The story of the Volsungs and Niblungs, with certain songs from the Elder Edda

London: F.S. Ellis, 1870

The translation of Icelandic sagas fits perfectly with Morris's personality. The sagas were written in Morris's idealized Middle Ages allowing him to immerse himself in his favorite period as he studied the tales. Additionally, by choosing to translate Icelandic mythology, Morris was keeping to a somewhat familiar genre of Norse mythology, but it was different enough from what was currently popular (classical mythology and Arthurian legend) to have an air of novelty about it.

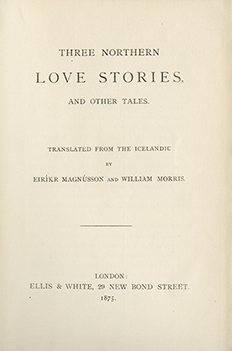

Three Northern Love Stories, and other tales

London: Ellis & White, 1875

The fact that these tales had not already been repeatedly translated allowed Morris to emphasize the portions of the sagas that suited his interests. In all Morris and his partner Magnusson published 11 Icelandic translations.

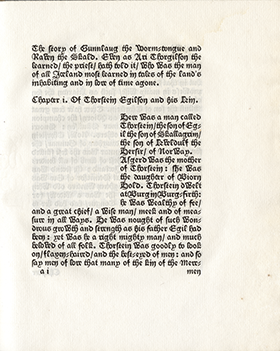

The Story of Gunnlaug the Worm-tongue and Raven the Skald

by Ali Thorgilson

Printed at the Chiswick Press for William Morris, 1891

This edition of The Story of Gunnlaug the Worm-Tongue and Raven the Skald demonstrates the attention that Morris devoted to his translated works. In addition to translating the story, Morris also designed and commissioned the creation of an original typeface which he thought best suited the tone of the work. Only a very limited test run of the text was commissioned. The project was abandoned because the typography was deemed illegible.

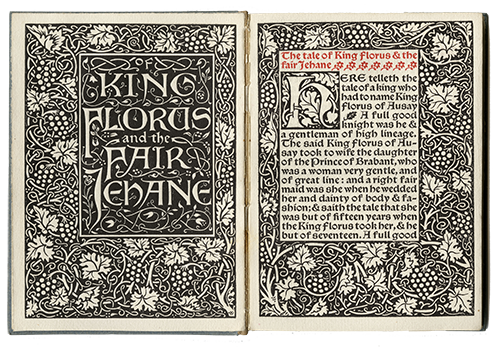

Of King Florus and the Fair Jehane

Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1893

Morris translated four medieval French tales into English from a volume called "Nouvelles Francoises en Prose du XIIIe siecle," in the 1890s. These were published together in three volumes by the Kelmscott Press and as a single volume, Old French Romances Done into English at George Allen, Ruskin House.

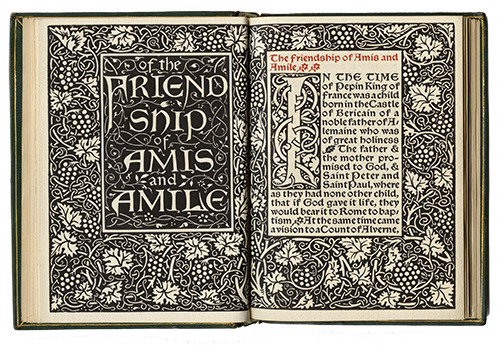

Of the Friendship of Amis and Amile

Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1894

Morris's translations were well received but garnered gentle criticism for their unique word choice.

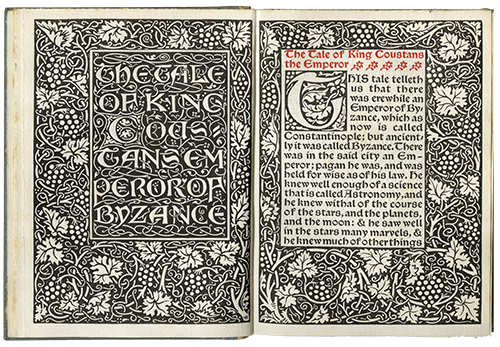

The Tale of the Emperor Coustans and Of Over Sea

Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1894

The criticism arose from the issue that they were neither a direct translation of the medieval French nor a translation into 'modern' English. Morris rewrites the stories in his imagined medieval English vernacular.

The Tale of Beowulf

Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1895

Morris's decision to translate Beowulf fits well within the scope of both his translations and his works printed at Kelmscott Press. Like most of his previous translations, Beowulf is a medieval text. Morris's translation of Beowulf received the same negative critical reaction as his Odyssey and Aeneid. The high regard with which Morris held the text he was translating caused Morris to stay too near the original text for the translation. The end result was not readily accessible to the average Victorian reader.