Bounties

Civil War Bounties

"Be Paid to Said Wife"

With few exceptions, women made only a marginal income during the nineteenth century. Husbands and fathers were the primary wage-earners, and their absence often placed great financial strains on families. A wife's income could only supplement, not replace, a husband's wages, and under common law wives did not control any earnings. Free African American women were especially limited in their choice of work and were often confined to domestic service.

The Civil War's call to arms left many working-class families on both sides of the conflict without a primary wage-earner. Both the Union and the Confederacy quickly resorted to drafts due to a lack of volunteers. The U.S. military employed a Federal bounty system that encouraged men to enlist, re-enlist, and to serve up to three years. In addition to the Federal bounty, state and local governments frequently allocated funds to furnish financial incentives for volunteers. This system allowed working men to leave for the duration of their enlistment without having to worry about supporting their loved ones exclusively through their meager and often irregularly paid monthly wage. However, as was often the case with compensation, African American soldiers and their families were not treated as fairly as whites when it came to bounties.

In Maryland, free black men and women often married slaves. Enslaved women who were married and had children with men who enlisted in the U.S. Colored Troops were not entitled to their deceased husband's bounty according to the February 6, 1864, Maryland bounty bill, section 4, which read: "If any person enlisted under this act shall die in service, leaving a wife or child, or children, the balance of the bounty may be due him shall, upon satisfactory evidence of his death, be paid to said wife, or to the legal representative of said infant children for their benefit; provided, that if the said wife or children be a slave or slaves, the said unpaid balance of bounty shall revert to the State."

Detail from William Still's The Underground Railroad.

Still, William, The Underground Railroad,1st ed. Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1872. Rare Books Collection, Special Collections, University of Maryland Libraries.

Detail from John Jacob Omenhausser Sketchbook

Maryland Manuscripts Collection, Special Collections, University of Maryland Libraries.

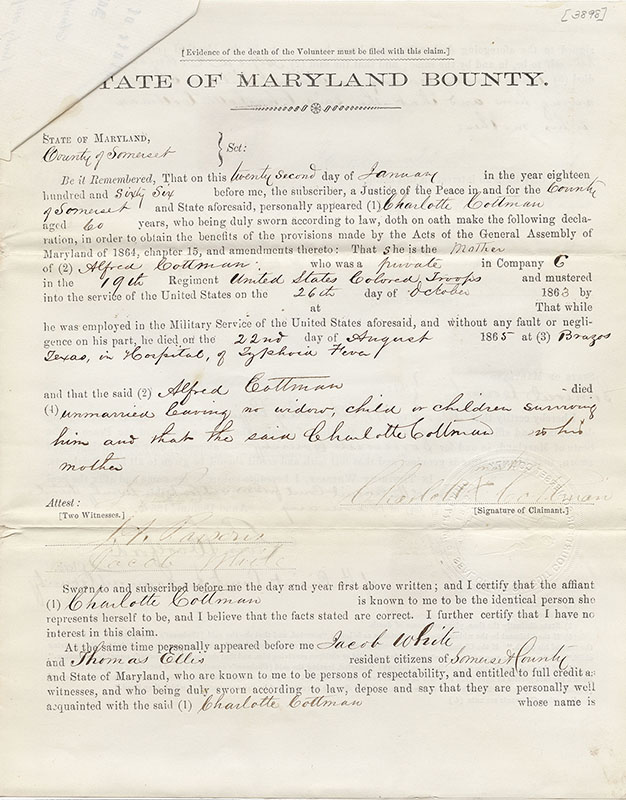

Bounty Documents, 1866

Bounty documents of Alfred Cottman (1846-1865), United States Colored Troops, January 22, 1866. In October 1863, President Abraham Lincoln called for an additional 300,000 volunteers to enlist. Alfred Cottman, an African American man from Somerset County, Maryland, enlisted in Company G of the Maryland 19th Regiment United States Colored Troops soon after Lincoln's proclamation. Cottman served for nearly two years before dying of typhoid fever in Santiago, Texas, in the summer of 1865. The remaining portion of his enlistment bounty was claimed by his mother, Charlotte Cottman.

Maryland Manuscripts Collection, Special Collections, University of Maryland Libraries.

- Research Tips -

Reading documents against the grain can lead to deeper understanding of women's experiences during the war. While bounty documents are often viewed as relating more to a particular soldier's history in the conflict (where he died, when and where he served), bounties affected women in countless, untold ways. In the bounty form shown below, Charlotte Cottman's "X," flanked by her first and last name (written in the hand of her legal, literate representative), is a reminder that this sectional conflict was not exclusively experienced by those who fought and fell on the battlefields. This bounty document represents the thousands of mothers, wives, and daughters who often claimed the final payments due to their deceased loved ones.