On the Front

Nursing the War's Wounded

"When I realize what I have stood against"

Neither the Federal nor the Confederate government was prepared to respond adequately to the unprecedented carnage of the Civil War. Two major armies in the eastern frontier - the Army of the Potomac (North) and the Army of Northern Virginia (South) - engaged in a long series of battles, including one at Antietam Creek in Maryland on September 17, 1862, which proved to be the bloodiest single day of the war. Local civilians, especially women, were highly motivated to do what they could to alleviate the suffering. In addition, many women who lived in the District of Columbia or other regions within the Eastern Seaboard volunteered their services to the Union Army and engaged in nursing in Maryland - assisting army surgeons on the battlefield, conveying medical supplies to armies, and staffing hospitals.

Much of this work was carried out on an ad-hoc basis and not all army medical staff welcomed the presence of women in war zones. Women of the lower social classes worked for meager wages, while women of the higher social classes often worked as volunteers. The necessities of the war undermined the prevailing assumption that military battlefields and hospitals were no place for women. Lack of full recognition and acknowledgement by the Federal government of women's contributions, however, persisted throughout the war and beyond.

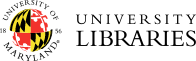

Numerous women helped provide medical care at Maryland's hospitals and battlefields. The Emmitsburg, Maryland-based Sisters of Charity overcame prejudice against women and anti-Catholic sentiment through their effective work with sick and wounded soldiers. Clara Barton left her work as a clerk in Washington, D.C., and attached herself to the Army of the Potomac. By the end of the war Barton had established a national reputation as an effective organizer of medical relief efforts on battlefields in Maryland and northern Virginia. Later in her career she was instrumental in establishing the American National Red Cross.

Harper's Weekly, October 11, 1862, Special Collections, University of Maryland Libraries.

Beyond surgery and hospital work, women were also engaged in letter-writing, the provision of refreshments, and performing miscellaneous errands for injured soldiers. These women wait outside a hospital in Hagerstown, Maryland.

Zoom in

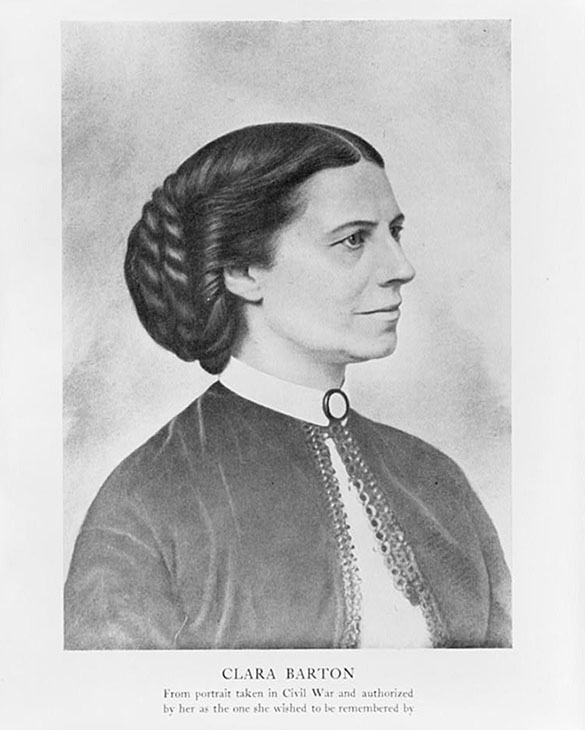

Letter from Clara Barton to Harriette Reed, 1900.

Clara Barton Papers, Special Collections, University of Maryland Libraries.

"... When I realize what I have stood against-,the props so slender, the weights so heavy, the way so dark, the fingertips so few,-the abyss so deep, & so rocky--the brain whirls as from a dizzy height-I dare not think of it-but step by step I hold my way- ..." The "Full details" button links to an entire folder of Barton correspondence with Reed. To view this particular letter go to pages 8-9 of the digital document viewer.

During the Civil War, Clara Barton formed a close relationship with Mrs. J. Sewall (Harriette) Reed of Massachusetts. Reed had served with Barton during the war and worked with her later in the American National Red Cross. In 1900 Barton attempted to secure more formal recognition by the Federal government of the American National Red Cross, including exclusive rights to use of its insignia. Writing from her home in Glen Echo, Maryland, Barton conveyed to Harriette Reed some of the emotions that came with her work in promoting the Red Cross. By extension, one could assign these thoughts to her travails during the Civil War.

- Research Tips -

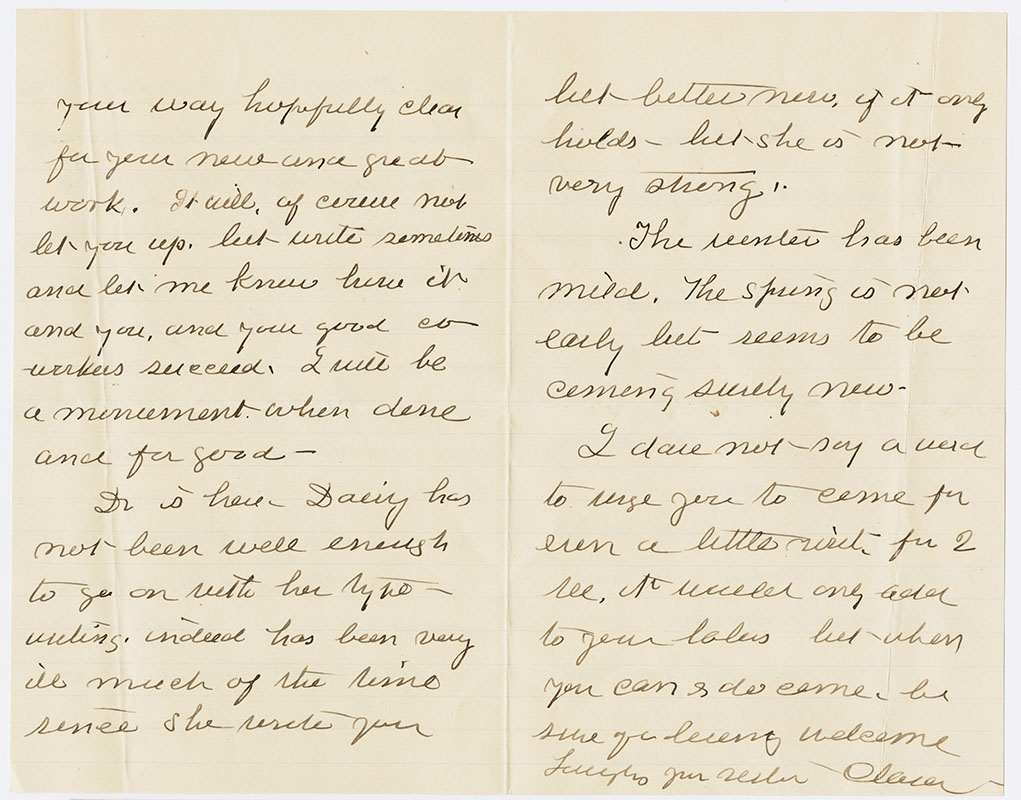

Nursing is probably one of the best-known contributions by women to the war effort. Popular images of the Civil War recurrently depicted women as nurses. Illustrations of the day romanticized white, middle and upper-class women's contributions to nursing, including writing letters for incapacitated, wounded soldiers; sitting for long hours by soldiers' bedsides; and supplying them with baskets of comforting food. While these illustrations provide some historical evidence, they also overlook other women's contributions. Poor women and African American women frequently worked as laundresses or cooks in support of hospital operations, but we do not often see them depicted in images from the time period. Critically examining and evaluating images, especially illustrations and staged photographs, is an important part of historical inquiry.

Image from Louisa May Alcott's Hospital Sketches, 1885

Rare Books Collection, Special Collections, University of Maryland Libraries.

" ... He never spoke again, but to the end held my hand close, so close that when he was asleep at last, I could not draw it away. Dan helped me, warning me as he did so that it was unsafe for dead and living flesh to lie so long together; but though my hand was strangely cold and stiff, and four white marks remained across its back, even when warmth and color had returned elsewhere, I could not but be glad that, through its touch, the presence of human sympathy, perhaps, had lightened that hard hour."

Louisa May Alcott, best-known for her literary career including her famous work Little Women (1868), volunteered as a nurse late in 1862. She served in the Maryland region, tending to wounded soldiers, until she was diagnosed with typhoid pneumonia the following year. Her book Hospital Sketches documents this period of her life. "John" was a soldier who died in Alcott's presence.

Zoom in

Correspondence with Members of Congress, circa 1890

Clara Barton Papers, Special Collections, University of Maryland Libraries.

The Women's Relief Corps, an auxiliary to the Grand Army of the Republic, proposed Federal government pensions for women who served as army nurses in the Civil War. The image link at right leads to various responses from members of the U.S. Congress to proposed legislation in 1890. Several of these Congressmen had personal recollections of having been nursed back to health by women during the Civil War. See page 31 of the collection in the link before.

Women as Soldiers and Spies

"...I am other than my appearance indicates"

Women served on the battlefield in various roles: nurses, doctors, vivandières (canteen carriers), daughters of regiments, flag bearers, laundresses, cooks, prostitutes, seamstresses, scouts, soldiers, and spies. Examples of women in Maryland volunteering as soldiers and spies during the war exist, but accounts of such feats by women are often difficult to confirm.

Women in Maryland with Southern sympathies were occasionally accused of spying and suffered the consequences. Federal forces and informants carefully watched the homes and families of known Confederate soldiers. In Baltimore in 1863 any secessionist activity was taken seriously. Confederate flag-waving, selling secessionist sheet music, writing letters to Confederate soldiers, and entertaining wounded Confederates, were all punishable offenses. At one point, Union General Robert C. Schenck reportedly rounded up women who appeared to be spying and sent them to live behind Confederate lines. Euphemia "Effie" Goldsborough of Talbot County and Baltimore, Maryland, suffered this fate. Goldsborough worked as a Confederate nurse at Antietam and at Gettysburg and was later accused of spying. She was forced to live in Virginia until July 1865, when her father brought her back to Baltimore.

In 1866, S. Emma E. Edmonds, a Unionist, described her escapades on battlefields behind enemy lines in her popular book, Nurse and Spy in the Union Army: The Adventures and Experiences of a Woman in Hospitals, Camps, and Battle-fields. While Edmonds was not from Maryland originally but rather a Canadian, she wrote of her experiences in Maryland, especially at the battle of Antietam. During the aftermath of the battle, Edmonds, who was herself dressed in soldier's garb, found a dying soldier on the battlefield. She quickly realized that the soldier was actually a woman, gave her comfort, and did not reveal the soldier's gender to others taking care of the wounded and the dead. Whether Edmonds's work is fact or fiction is uncertain.

Nurse and Spy in the Union Army, 1866

Rare Books Collection, Special Collections, University of Maryland Libraries.

S. Emma E. Edmonds with a dying female soldier in the aftermath of the battle of Antietam, from her book Nurse and Spy in the Union Army.

Zoom in

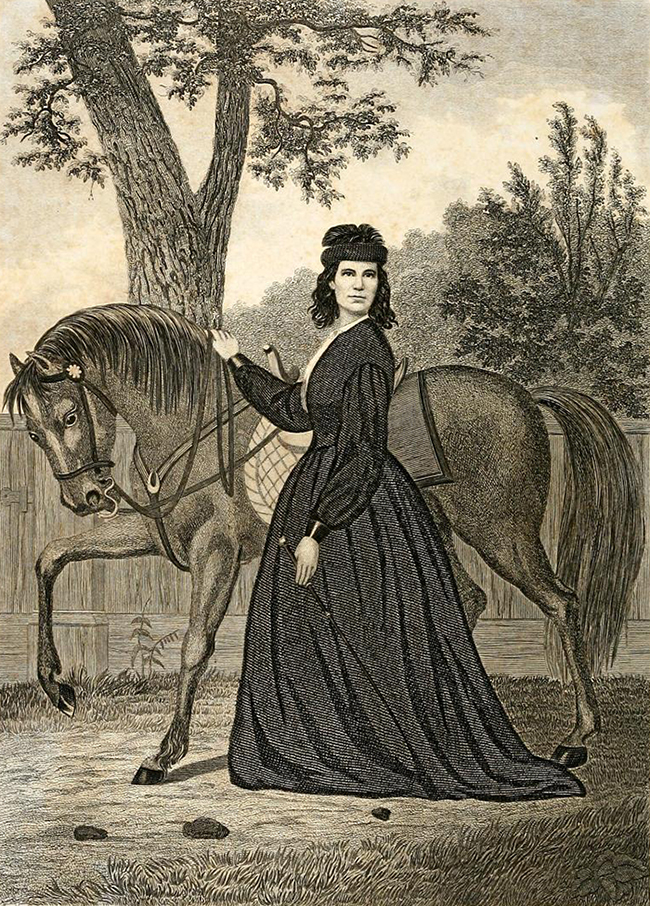

Nurse and Spy in the Union Army, 1866

Rare Books Collection, Special Collections, University of Maryland Libraries.

According to her book, S. Emma E. Edmonds, shown here dressed as an upper-class white woman during the Civil War, took advantage of the war to cross gender and racial boundaries. On various occasions in her narrative Edmonds purports to have disguised herself successfully as a white, male soldier; an African American, male slave; and an African American, female slave.

- Research Tips -

Nursing is probably one of the best-known contributions by women to the war effort. Popular images of the Civil War recurrently depicted women as nurses. Illustrations of the day romanticized white, middle and upper-class women's contributions to nursing, including writing letters for incapacitated, wounded soldiers; sitting for long hours by soldiers' bedsides; and supplying them with baskets of comforting food. While these illustrations provide some historical evidence, they also overlook other women's contributions. Poor women and African American women frequently worked as laundresses or cooks in support of hospital operations, but we do not often see them depicted in images from the time period. Critically examining and evaluating images, especially illustrations and staged photographs, is an important part of historical inquiry.