African American Suffrage and the 15th Amendment

"The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude"

- 15th Amendment, Constitution of United States of America -

Voting rights for marginalized, minority, and poor communities were not guaranteed in American democracy. In the 18th and 19th centuries, many abolitionists fighting to end slavery also advocated for citizenship and voting rights for African Americans. After the 13th Amendment formally ended slavery in 1865, former abolitionists and voting rights advocates debated the merits of prioritizing the voting rights for African American men versus a strategy to ensure universal suffrage for all disenfranchised voters, which would have included women.

Prominent abolitionists, including Lucy Stone and Frederick Douglass, advocated for a strategy focused on African American male suffrage. Others, however, argued that a new amendment should ensure the right to vote for all citizens. As a result of these debates, many prominent white women in the anti-slavery movement shifted away from abolitionist organizations to focus their attention on advocating for women's suffrage.

Following a difficult and divisive political process, the 15th Amendment was ratified in 1870 in an attempt to restrict disenfranchisement of African American men. In the years immediately following the passage of the 15th Amendment, voter registration and political participation among Black men increased dramatically. However, the trend lasted only a few years before discriminatory practices and laws effectively and "legally" disenfranchised African American men.

Explore items related to the social and political climate prior to the passage of the 15th amendment, the work of abolitionists, and support and opposition to African American suffrage.

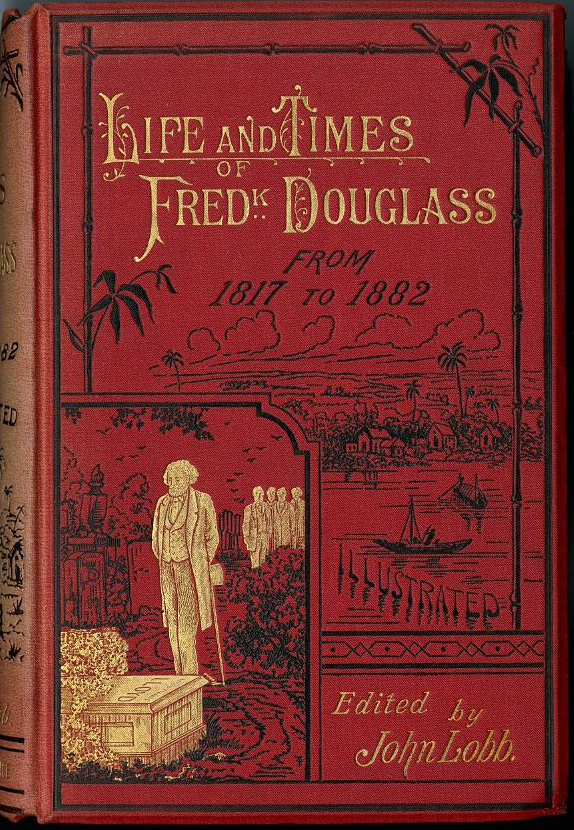

“The Fifteenth Amendment and its Results.” Drawn by G.F. Kahl. Baltimore: Lithograph by E. Sachse & Co., circa 1870.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

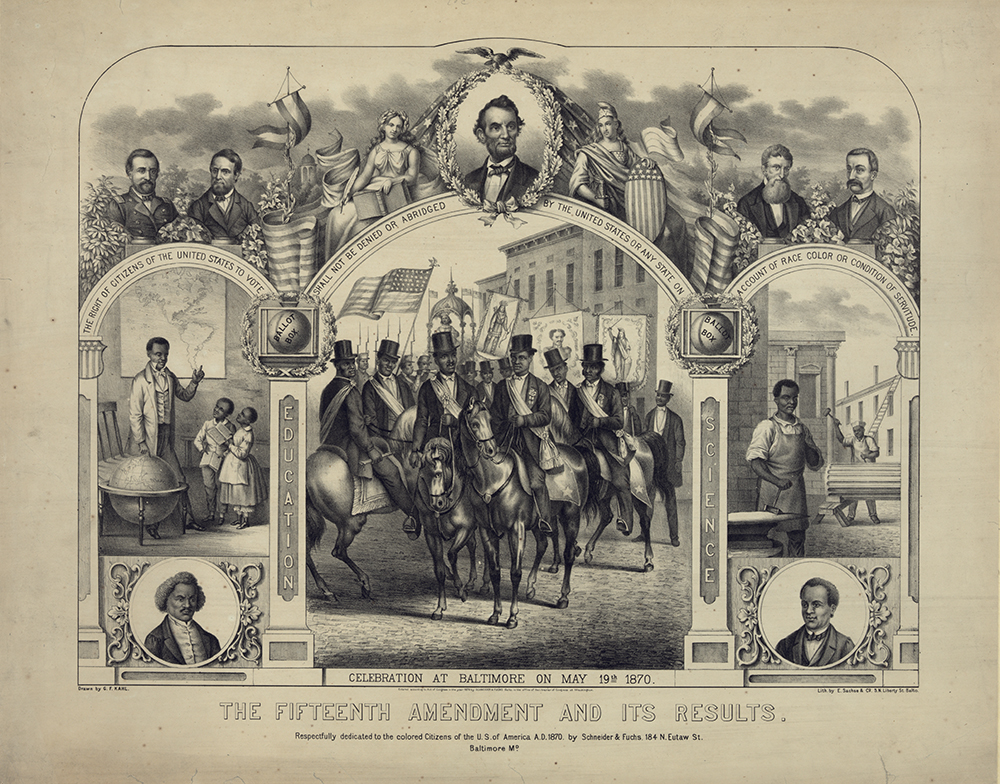

"The first vote." Drawn by A.R. Waud. Harper's Weekly, 16 November 1867.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

WARNING

Offensive LanguageThe archival resources in this exhibition contain offensive and outdated language. We chose not to censor these items in order to accurately represent the bias and prejudice of the time. We strongly condemn the use of such language and ask exhibition visitors to engage with this material carefully and critically. Explicit warnings have been provided for those items with the most offensive language.

Prior to the Amendment

The Democrat’s Almanac, and Political Register

New York, Office of the Evening Post, 1859.

Rare Books collection

The “Naturalization and the Right of Suffrage” section outlines the suffrage requirements by state on pages 21 through 24.

No Compromise of Human Rights: No Admission in the Constitution of Inequality of Rights, or Disfranchisement on Account of Color

Charles Sumner

Washington, Congressional Globe Office, 1866.

Rare Books collection

Charles Sumner argues against a proposed amendment that would base political representation on the eligible voting population as opposed to the entire population of a state, including those who had no voting rights.

He argues that the inclusion of African Americans in the elective franchise was unequivocally decided with the abolition of slavery.

It is clear from Sumner’s argument that the 13th amendment did not go far enough to ensure that African Americans would be protected from discriminatory legislation and that further protections would be needed to solidify their rights.

Address of the Democratic Executive Committee for Baltimore County

Baltimore, Maryland, 1865.

Maryland Rare Books collection

Disenfranchising legislation was debated for a variety of reasons.

This opinion against the Registry Law argues that there is no need to further the disenfranchisement of former Confederate supporters. The author further argues that a person should not be denied the right to vote based on a judgement of their character.

The Constitutional Amendment

1864.

Rare Books collection

This document provides an argument for why the 13th amendment is needed after it was rejected by the House of Representatives. The author argues that one of the main tenets of our Constitution is the right to a republican government that derives its power from the people, all people.

Abolitionists

States were slow to ensure that the rights of the newly freed African Americans. Abolitionists did not rest after the passage of the 13th amendment, but continued to work to ensure voting rights for African Americans.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was an abolitionist, women's rights activist, and acclaimed poet born in Baltimore in 1825. Born to free parents and orphaned at three, Watkins was raised by her maternal uncle Rev. William Watkins, an abolitionist and civil rights activist, and his wife Henrietta. She was educated at her uncle's school, the Watkins Academy for Negro Youth.

Watkins published her first book of poetry, Forest Leaves, at the age of 20. She went on to publish another book of poetry, many short stories, and several novels, including her most popular work Iola Leroy, or Shadows Uplifted. Watkins' writing often addressed issues of race, gender, and their intersections.

In her discussions of intersectionality, Watkins alienated many white suffragists. She criticized the racism and selfishness of their refusal to support the 15th Amendment.

In response, she helped found the American Woman Suffrage Association, which actively supported the 15th Amendment. She was also active in the "Colored Section" of Philadelphia's Woman's National Association of Colored Women (NACW). The NACW focused on both black and women's issues such as women's suffrage, lynching, and Jim Crow laws, and became the most prominent organization of the African American Women's Suffrage Movement.

Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects

Frances Ellen Watkins

Philadelphia, Merrihew & Thompson, printers, 1857.

Maryland Rare Books collection

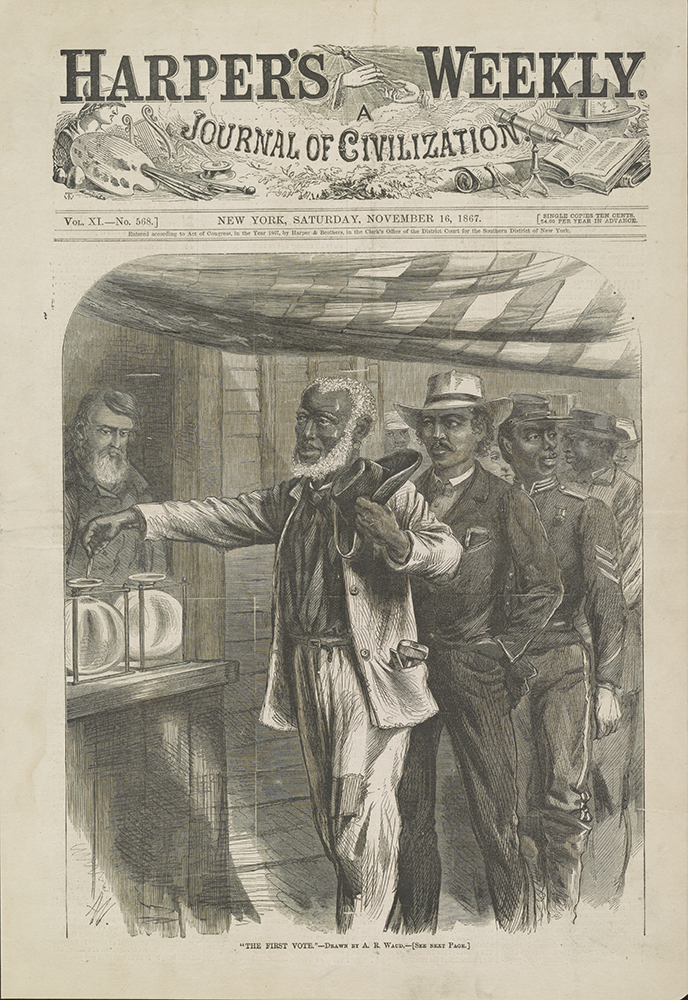

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass was an influential abolitionist, author and social reformer. Douglass was born into slavery circa 1818 in Talbot County, Maryland. He escaped to Philadelphia in 1838 with his partner Anna Murray, who he had met in Baltimore the previous year. They eventually settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts, an abolitionist center, and began their family. In New Bedford, Douglass regularly attended anti-slavery meetings and became a preacher. In turn, he developed impressive oratorical skills.

For the rest of his life, Douglass was a champion of equal rights. In addition to his anti-slavery work, he fought for women's rights and equal rights for Native Americans and Chinese immigrants. In 1848, Douglass attended the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women's rights convention in the U.S. At Seneca Falls, Douglass spoke in favor of women voting before the suffrage movement has even truly begun. In his speech, he noted that he could not accept suffrage as a black man if women could not vote too.

However, after the Civil War, his feelings shifted. Debate over the 15th Amendment, which guaranteed suffrage for black men, caused Douglass to split with some women suffragists. While Douglass argued that tying women's suffrage to black men's suffrage would hinder both movements, many white suffragists refused to support any legislation that divided them. Douglass still passionately supported women's suffrage, though, and never abandoned the cause.

Annual Report of the Philadelphia Female Anti-slavery Society

Philadelphia Female Anti-slavery Society, 1838.

Rare Books collection

Many American women suffragists began their activism by supporting abolition and African American suffrage, including Susan B. Anthony.

She, and many others like her, failed to continue to support African American suffrage after it became clear that politicians were disinclined to support universal suffrage, prioritizing African American males’ suffrage rights.

This bitter rift is marked by racism and resulted in the exclusion of black women suffragists from many parts of the women’s movement.

Annual Report of the Philadelphia Female Anti-slavery Society

Philadelphia Female Anti-slavery Society, 1856.

Rare Books collection

The Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society was formed by women who had been denied positions in the American Anti-Slavery Society. This group is often pointed to as one of the only racially integrated abolitionist groups of the time. Over the years, members included notable abolitionists including Charlotte Forten and her three daughters, Harriet, Sarah, and Margaretta, Lucrieta Mott and Angelina Grimké.

Annual Report of the Philadelphia Female Anti-slavery Society

Philadelphia Female Anti-slavery Society, 1857.

Rare Books collection

Annual Report of the Philadelphia Female Anti-slavery Society

Philadelphia Female Anti-slavery Society, 1859.

Rare Books collection

Annual Report of the Philadelphia Female Anti-slavery Society

Philadelphia Female Anti-slavery Society, 1863.

Rare Books collection

Support for African American Suffrage

The Equality of All Men Before the Law: Claimed and Defended

William D. Kelley, Wendell Phillips, and Frederick Douglass, et. al

Boston, Press of Geo. C. Rand & Avery, 1865.

Maryland Rare Books collection

Three speeches by prominent abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass, who said: “What I ask for the negro is not benevolence, not pity, not sympathy, but simply justice.”

The African's Right to Citizenship

Philadelphia, James S. Claxton, 1865.

Rare Books collection

This pamphlet provides an example of a progressive argument in support of Black citizenship. The author argues for expansive human rights, regardless of race or country of origin, declaring that all humans are equally capable and deserving and that any differences routinely pointed to as signs of inferiority, were only brought about by the systemic maltreatment of African Americans at the hands of Whites.

The Great Question for the People! Essays on the Elective Franchise; or, Who Has the Right to Vote?

John Hancock

Merrihew & Son, Printers, 1865.

Rare Books collection

Some arguments that supported the inclusion of African American voters still argued for the exclusion of certain populations. This argument pushed for an exclusive educated electorate, regardless of race.

Hon. W.D. Kelley, of Pennsylvania, on the Constitutional Regulation of Suffrage

Washington, D.C., 1866.

Maryland Rare Books collection

Opposition to African American Suffrage

A Fair Statement, The True Issue: Negro Suffrage No Part of the Union Platform

c. 1866.

Rare Books collection

This statement supports the proposed 14th amendment, which would expand the legal definition of citizenship. The 14th amendment also requires that Congressional representatives be apportioned based on the total number of eligible voters in a given state, as opposed to being based on the total population.

The author argues that this amendment does not grant African Americans the right to vote, but rather allows states to dictate their own rules for who can vote. The proposed amendment challenges the “three-fifths compromise” that enabled slave holding states to count the population of enslaved people toward their population count used to allocate Congressional representation.

Letter from Edward a. Lynch, Esq., Whig Candidate for the Legislature of Maryland

Edward A Lynch

1840.

Maryland Rare Books collection

Racism is often utilized as a political weapon. Lynch was hoping to appeal to voters by declaring his opponent a supporter of African American suffrage.

Gov. Swann's Speech at the Conservative Mass Meeting, in Monument Square, Thursday, June 21, 1866

Thomas Swann

Baltimore, 1866.

Maryland Rare Books collection

Maryland’s geographical position in the mid-Atlantic, between the Union and Confederacy, was reflected in it's politics. Governor Swann declared himself and his policies progressive, while supporting the racist policy of President Johnson. This speech effectively displays the defensive politics of Maryland.