Women's Suffrage and the 19th Amendment

"The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex."

- 19th Amendment, Constitution of United States of America -

Closely tied to the abolitionist movement and inspired by the suffragettes in England, women’s suffrage leaders in America began building toward a large scale, organized effort to demand the right to vote for women. While the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848 is widely recognized as the official beginning of the movement, in reality women fought for equal rights as long as they were denied them. Over many decades, women’s suffrage organizations broke apart and reformed as debates over tactics and practices of inclusion and exclusion divided groups and individuals.

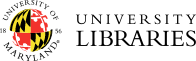

Around the turn of the 20th century, vigor in the women’s suffrage movement was reborn on a national scale, particularly with the rise of young women in the movement. Many of these new leaders believed in the importance of employing dramatic and militant practices to capture the attention of politicians and the American population. Picketing, parades, and other confrontational methods employed by organizations like the National Women's Party spurred the agitation of police and politicians. As a result, women were arrested, fined, jailed in harsh conditions, and violently force fed during hunger strikes.

After more than 80 years of fighting, these suffragists succeeded in convincing politicians to back the 19th Amendment. Passed by Congress in 1919 and fully ratified into law in 1920, it formally secured the right of women to vote in America.

With suffrage ensured, many of these same women who had become active in the movement turned towards educating and mobilizing women around their newfound political power. New women’s groups and organizations, including the League of Women Voters and the National Organization of Colored Women, focused on fighting for more expansive equal rights, ending lynching and disenfranchisement in the south, and increasing political awareness and participation among the newly enfranchised population.

Explore items related to the political and moral arguments supporting and opposing women's suffrage and items related to suffrage organizations.

Political Arguments

Objections to Woman Suffrage Answered

Alice Stone Blackwell

Just Government League of Maryland, Baltimore, c. 1910.

Maryland Book collection

This is a thorough examination and refutation of the arguments commonly made against women suffrage. The author responds to these 34 arguments, including:

- Women “don’t understand business”

- Women as voters could disrupt the established “division of labor”

- Women suffrage “will lead to family quarrels and increase divorce”

- If granted the franchise, women should also serve in military and police forces.

Address in Favor of Universal Suffrage

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

American Equal Rights Association, Albany, NY, 1867.

Women’s Studies pamphlet collection

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was a powerful and problematic advocate for suffrage rights. She began her advocacy working with groups such as the American Equal Rights Association (AERA), who focused on universal suffrage. Her racist ideologies eventually led her and professional partner Susan B Anthony to leave the AERA in order to form one focused solely on advancing women’s suffrage.

In this speech, Stanton argues that women and African Americans should be elected as delegates to the Constitutional Convention so that they might represent the interests of these groups in the revision of the New York state constitution. She points out that the previous state constitutions became more restrictive over time, securing voting rights only to those who were white, free, male and property owners.

“The simple point we now press is this: that in a revision of our Constitution, when the State is, as it were, resolved into its original elements, ALL THE PEOPLE should be represented in the Convention which is to enact the fundamental laws by which they are to be governed the next twenty years.”

Woman suffrage not to be tolerated although advocated by the Republican candidate for the vice presidency

Archer Stevenson F. & J. Rives & Geo. A. Bailey, Washington, 1872.

Maryland Rare Books collection

An early, and very expansive, argument against a proposed bill to expand voting rights to women. The opening response from a Maryland Representative states:

“Sir, who but a veritable fanatic could have believed, ten years ago, that the question, ‘Shall women be allowed to vote?’ would so soon come to be considered throughout the greater portion of our country as one to be seriously entertained, gravely pondered on, and nicely decided, by the various political assemblies, law-making bodies, and judicial tribunals of the land?...But this socio-political aspect of affairs has long since ceased to be merely funny. It has become so serious, indeed, that al who are at heart opposed to the success of the new movement must leave off regarding these innovators as mere petticoated harlequins, who, with cap and bells, and clownish grimace, once made us hold our sides with pain of laughing. A monstrous army is now coming down upon us-a hundred thousand ‘whirlwinds in petticoats’ - which we must meet firmly or be overwhelmed by storm. The little wife has attained to such size and strength that her blows now make the big man wince; the wee finger-nails have grown to talons, and tear now where they only tickled before; and if the big, good-natured fellow does not look well to the guard, he will be throttled, stretched on his back and brought to such terms as he dreamed not of a short while ago.”

Governor Ritchie’s Address to the Special Session of the General Assembly of Maryland

Annapolis, 1920.

Maryland Book collection

After the passage of the 19th amendment, the Governor of Maryland called a Special Session of the General Assembly in order to urge them to develop new procedures and legislation that would support the sudden and substantial growth of the franchise.

Universal Suffrage

Thomas W. Palmer

Washington D.C., 1885.

Women’s Studies Pamphlet collection

This statement was presented on the Senate floor in support of the proposed 19th amendment. The author begins by responding to a report submitted by the Senate minority which reflected commonly held sentiments opposing women’s suffrage at the time. He states:

“It seems to me that we should divest ourselves to the utmost extent possible of these entanglements of tradition and judicially examine three questions relative to the proposed extension of suffrage: First. Is it right?Second. Is it desirable?Third. Is it expedient?if these be determined affirmatively our duty is plain”

Moral Arguments

Report of Special Committee on Woman Suffrage

Vermont, 1869.

Women’s Studies Pamphlet collection

Remonstrant View of Woman Suffrage

1884.

Women’s Studies Pamphlet collection

This pamphlet takes a stand against women’s suffrage, arguing that

“modern thought and feeling are a sure guarantee for the future against women’s ‘wrongs;’ that the power of good for the best women would be lessened by the ballot; that the collective vote of the sex would be a great injury to the country in general, and the sex in particular; that whatever unnecessarily impairs the efficiency of government is a pure invasion of the rights of all.”

The Centennial Situation of Woman

Alexander H. Bullock

1876.

Women’s Studies Pamphlet collection

Right and Strength in Equal Suffrage

Plainfield, New Jersey, 1910.

Women’s Studies Pamphlet collection

Some Rights and Exemptions Given to Women by Massachusetts Law

Boston, 1911.

Women’s Studies pamphlet collection

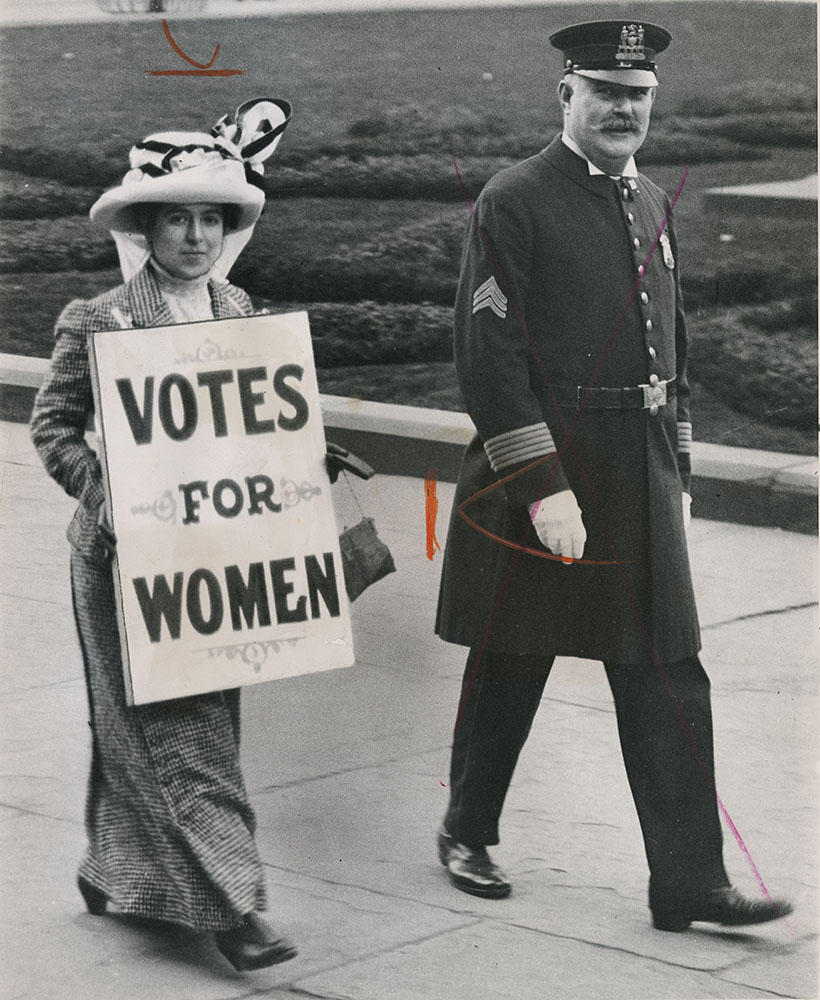

Suffrage Organizations

The Revolution

New York, 1868.

Women’s Studies Pamphlet Collection

The Revolution was established by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton in New York City between 1868 and 1872. While its primary focus was on women’s suffrage, the newspaper also covered other gender issues like divorce and employment, labor issues, finance and politics, and race-- though these opinions were often racist in tone and content. The Revolution notoriously opposed the Fifteenth Amendment; Stanton and Anthony opposed the passage of any suffrage amendment that did not enfranchise women.

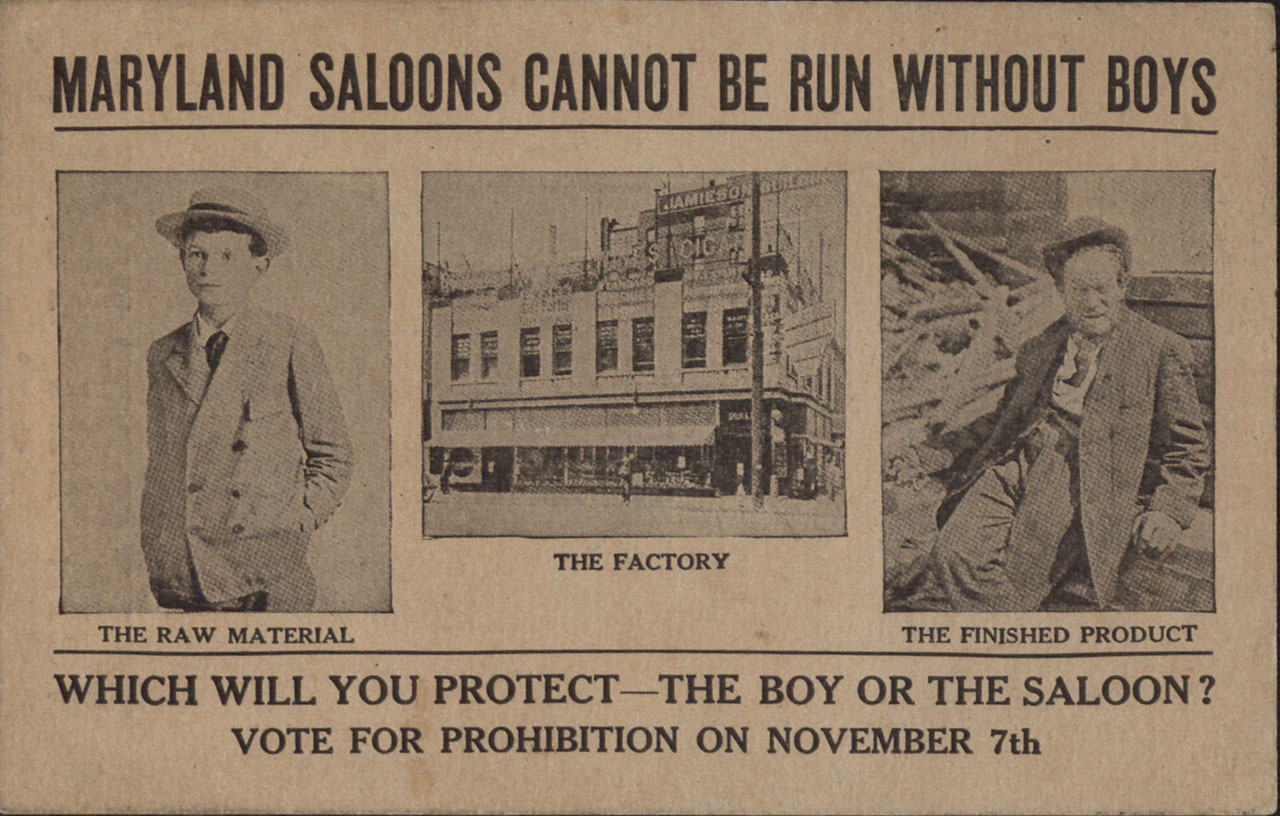

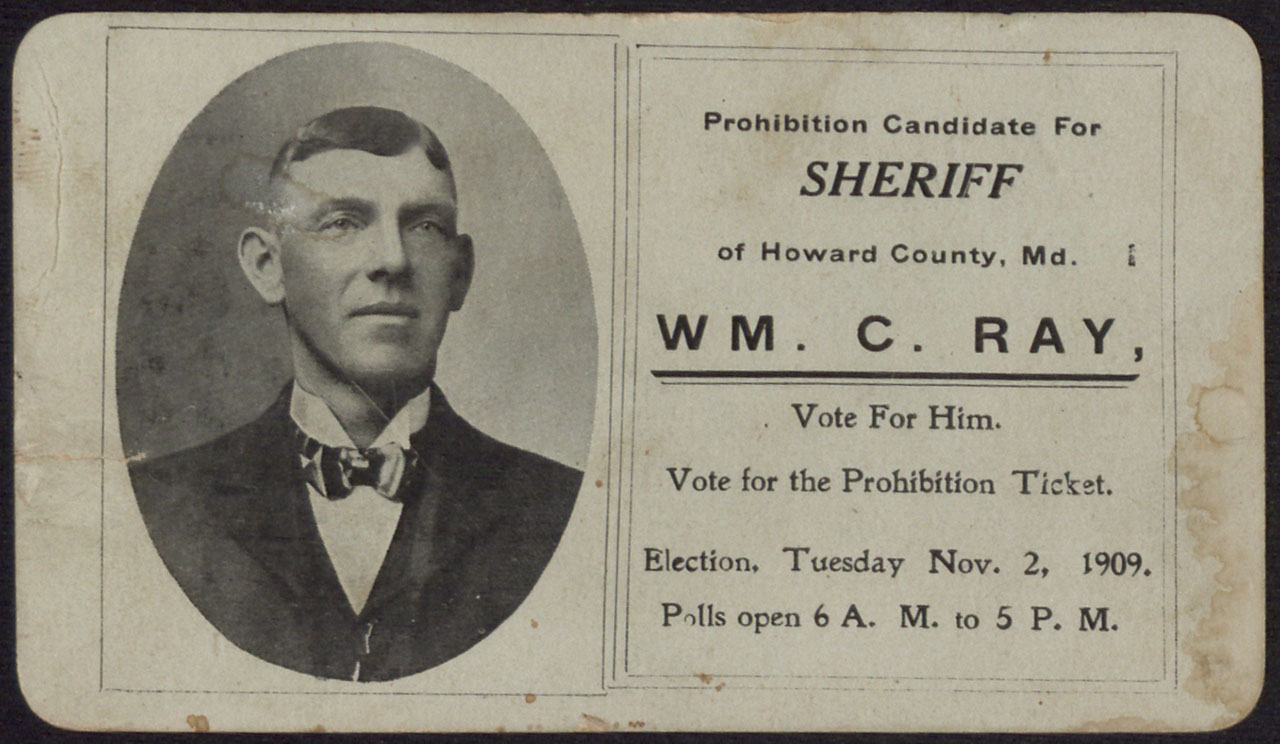

Woman’s Christian Temperance Union

The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) formed in Cleveland in 1874. Its platform encouraged the prohibition of alcohol, tobacco, and illegal drugs in the U.S., driven partially by a desire to protect wives and children from the physical, emotional, and economic consequences of living with men who were dependent on alcohol. Under the leadership of Frances Willard in 1879, the WCTU became one of the most influential women’s organizations in the country. White, protestant women made up the majority of members. Some regions formed “Colored Sections,” which gave women like Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, a notable black activist, a voice in the movement.

At the turn of the century, assumptions about women’s moral superiority increased society’s comfort with their presence in the public sphere. Accordingly, the WCTU expanded its platform to include progressive reforms such as labor legislation, prison reform, and women’s right to vote. As to voting rights, WCTU members argued that suffrage would cure America’s moral ills. In 1891, Frances Willard argued that “an organized movement of women will best conserve the highest good of the family and the State.”

Though controversial, the WCTU’s efforts were crucial to the passage of the 19th amendment. Membership decreased sharply following Prohibition, but the WCTU remains active today as the oldest continuous women's organization in the world.

Constitution of the Maryland Woman’s Christian Temperance Union

Maryland, 1886.

Maryland Temperance collection

WCTU Annual Reports

Union Bridge, Maryland, 1889.

Maryland Temperance collection

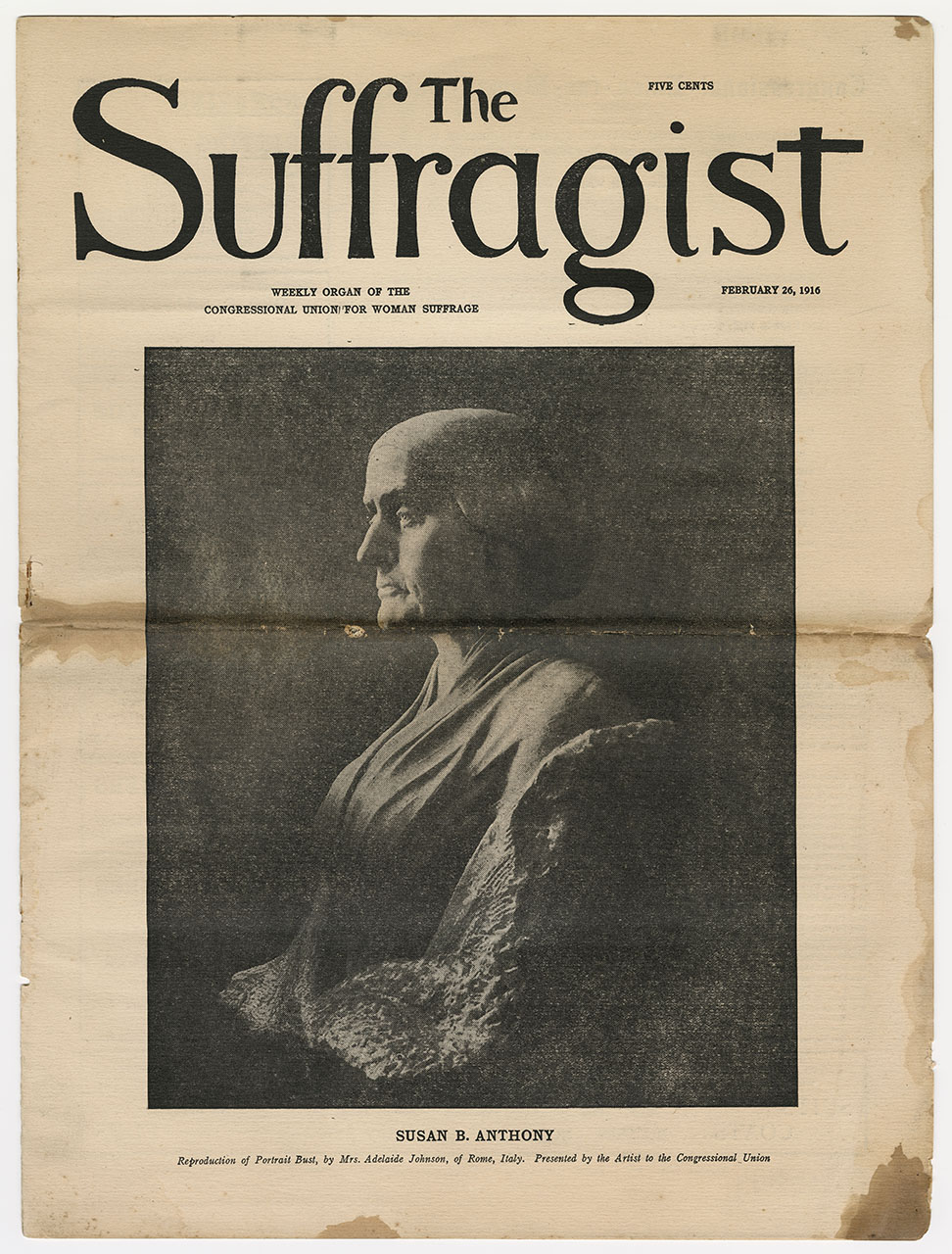

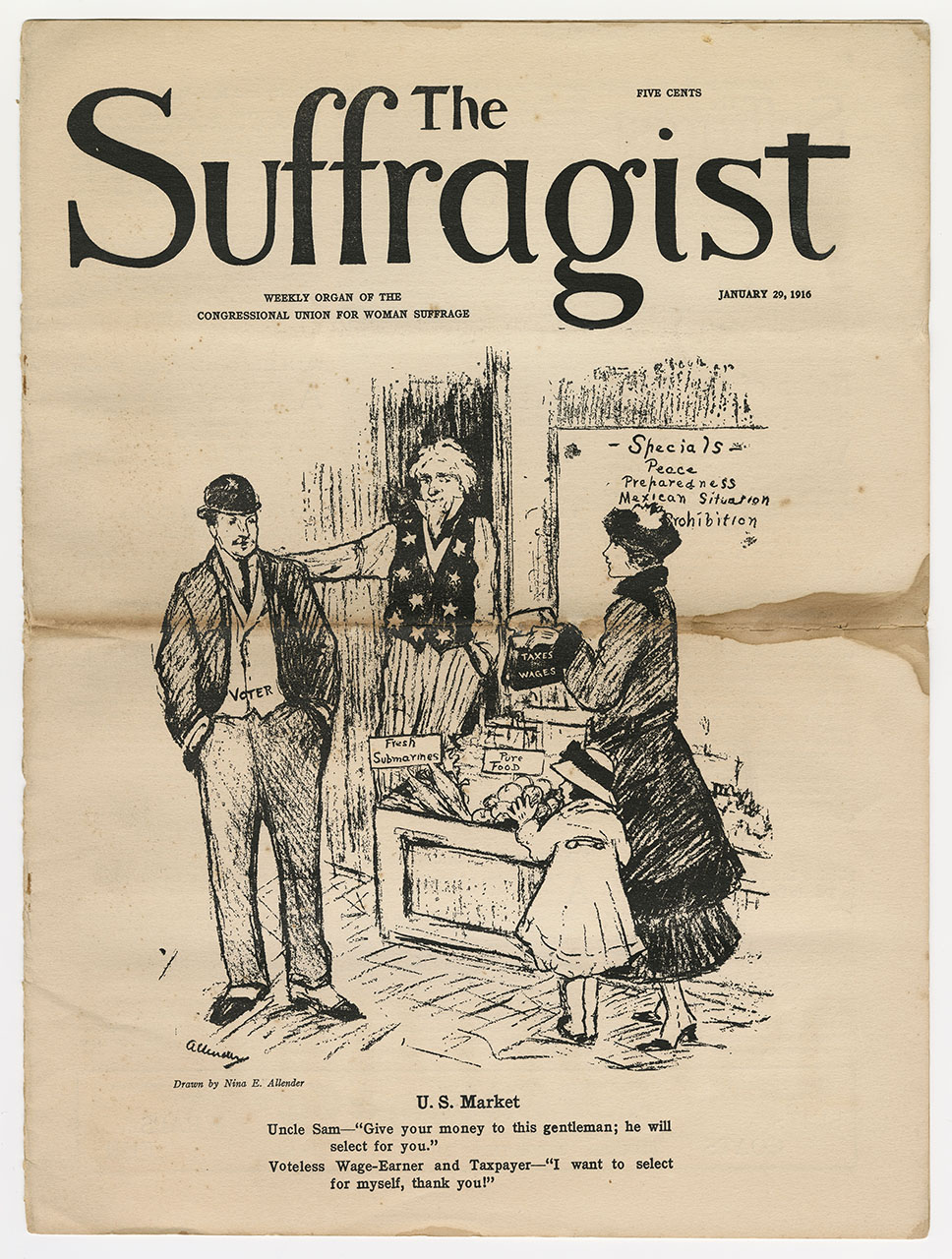

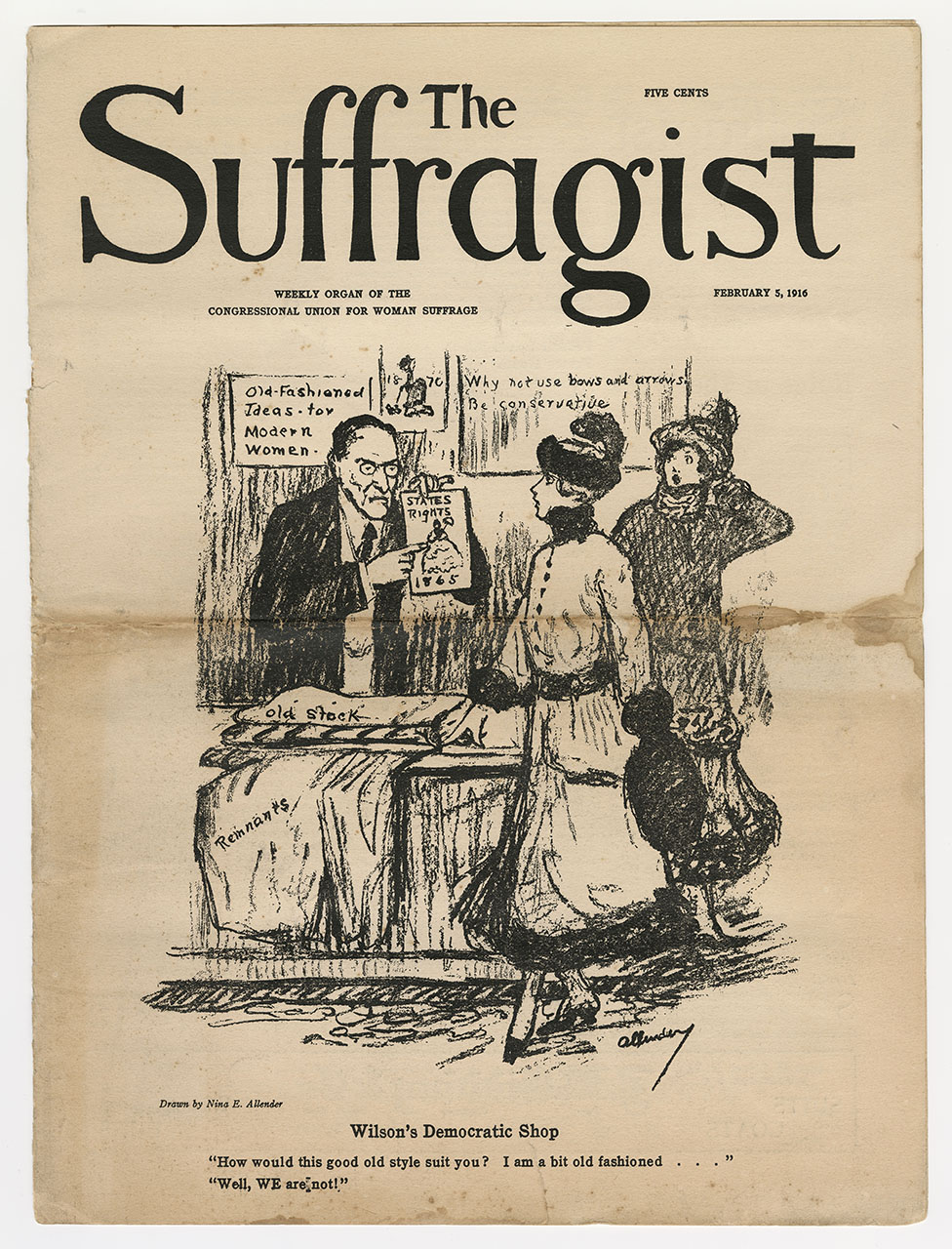

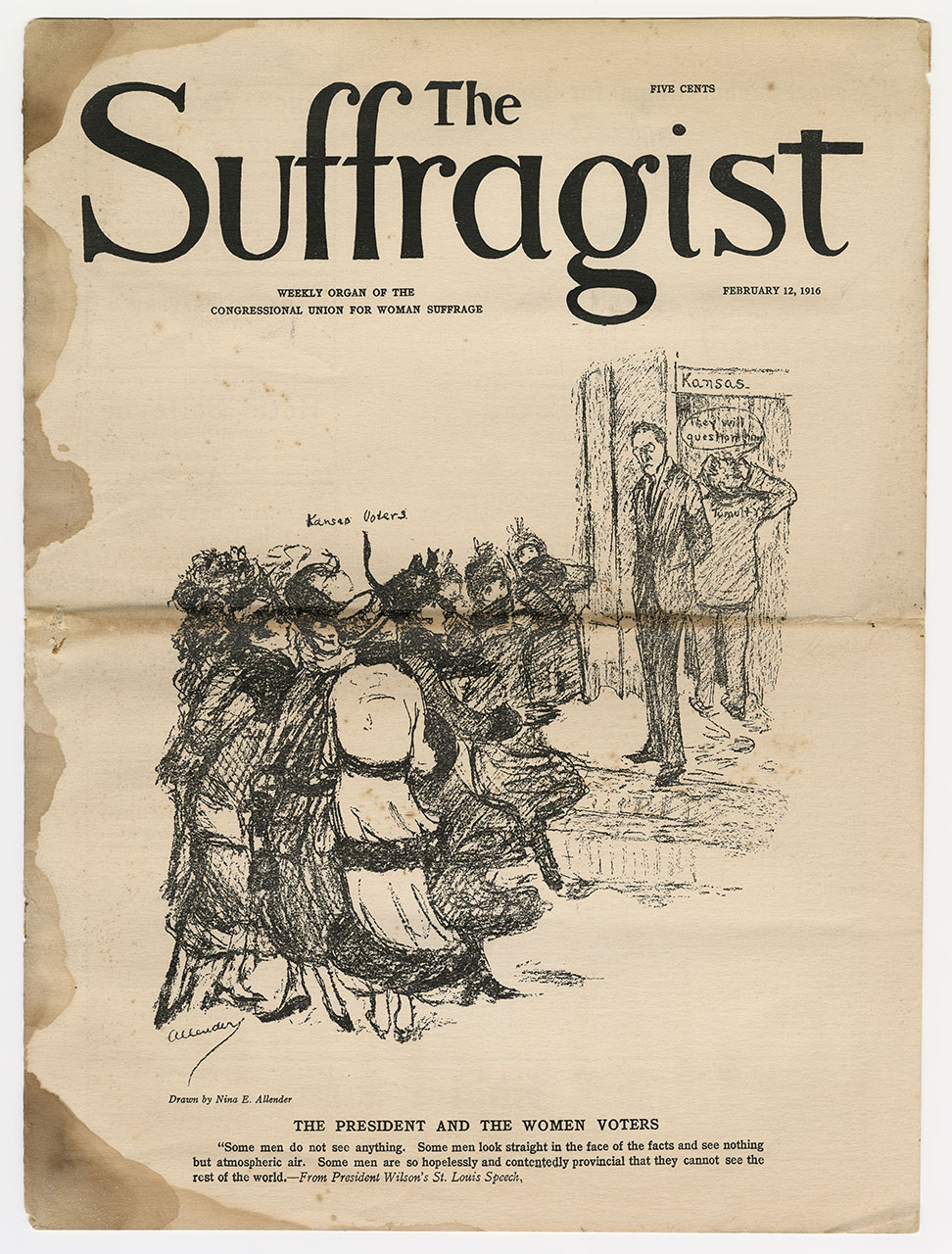

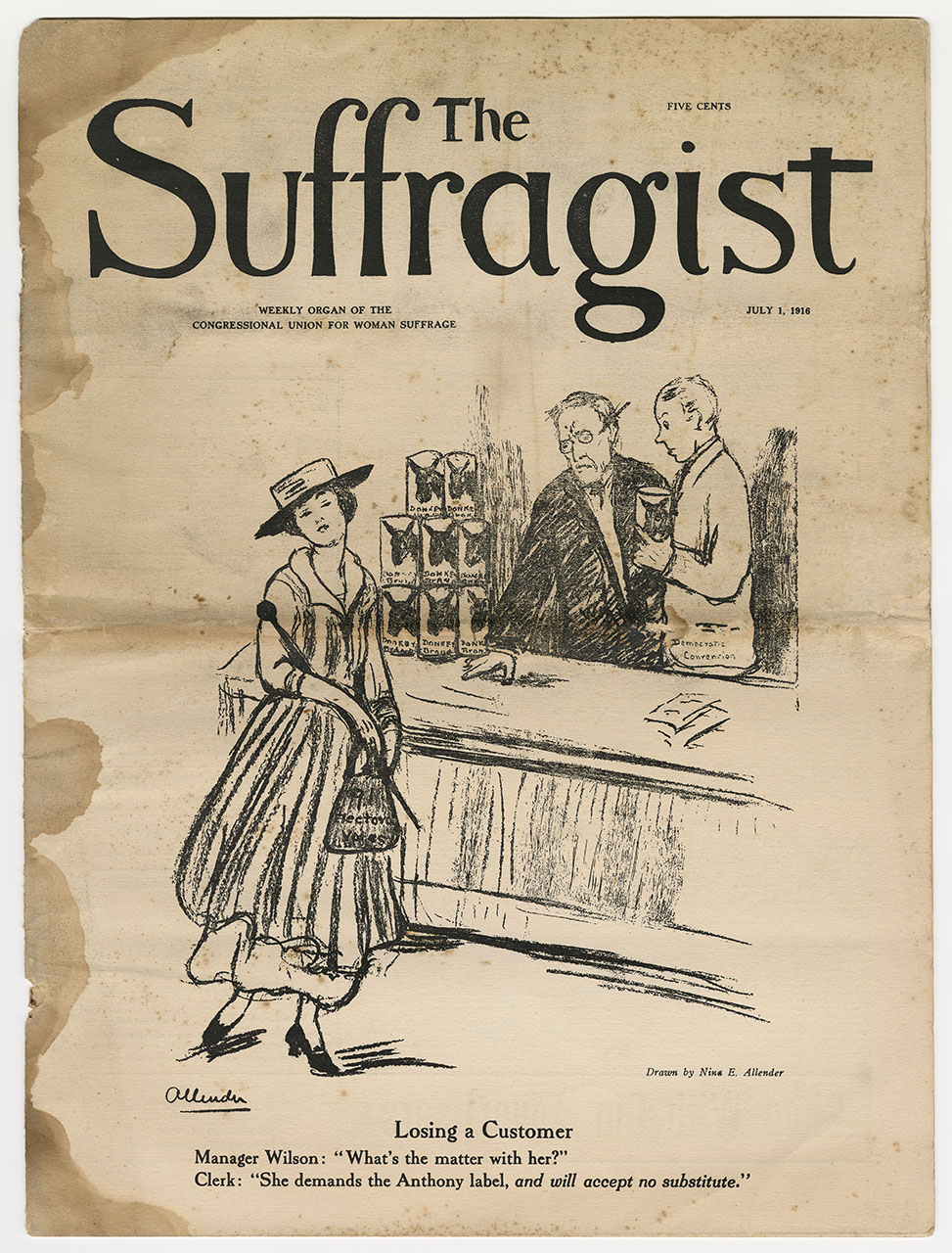

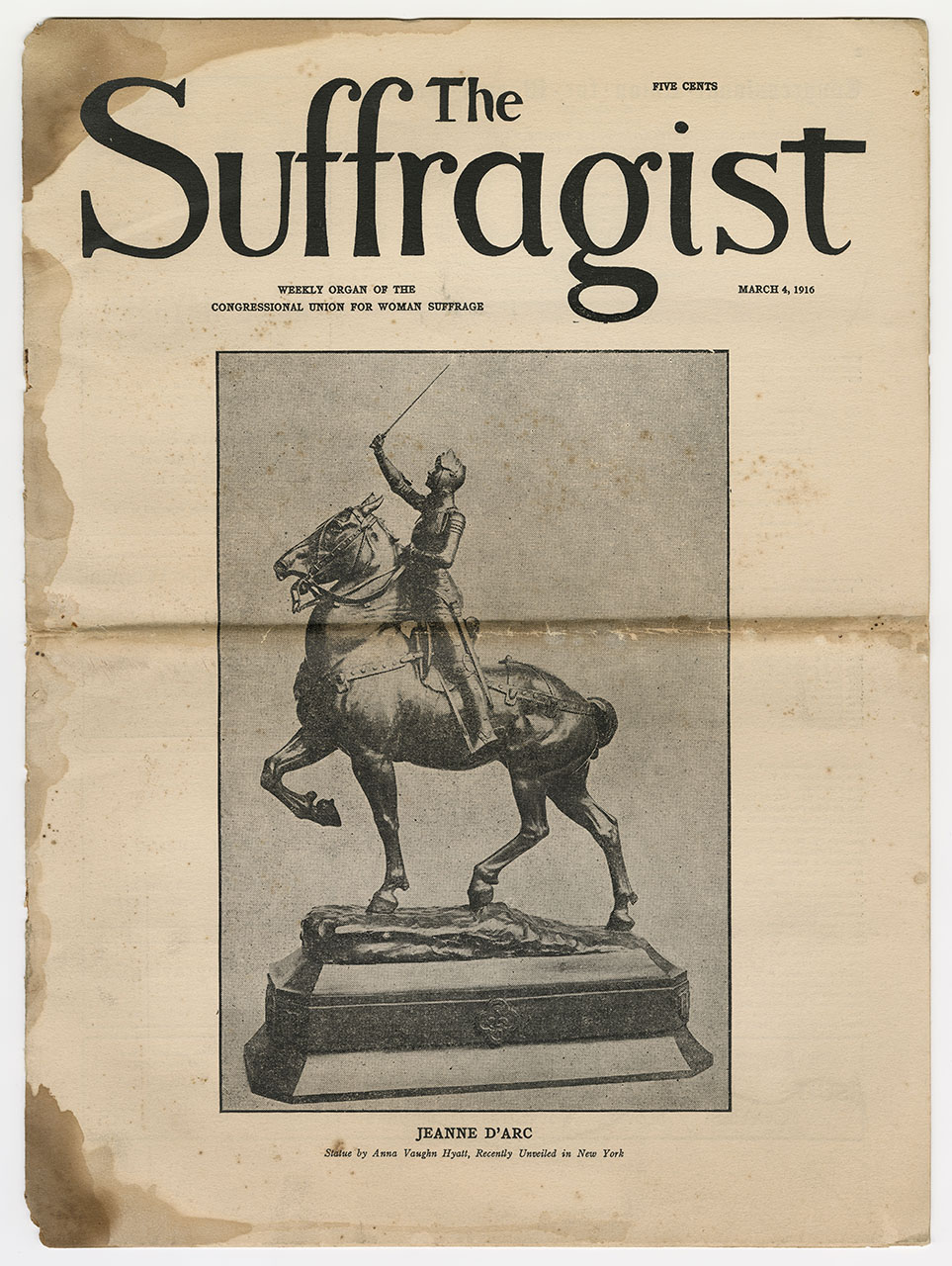

The Suffragist

The Suffragist, first published in November of 1913, was a weekly newspaper published by Alice Paul and the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (later the National Woman’s Party).

Suffragist and muckraker journalist Rheta Childe Dorr was the newspaper’s first editor. Baltimore suffragist Edith Houghton Hooker, who was the founder and editor of Maryland Suffrage News, took over the role in 1917. Artist Nina Allender illustrated its popular cover-art and political cartoons. Allender’s portrayal of suffragists was new and influential, which depicted suffragists as “New Women:” young, conventionally attractive, intelligent, and courageous.

When Alice Paul and other members of the National Woman’s Party began picketing the White House in 1917, the newspaper used its non-mainstream status to expose the harsh treatment of protesters as political prisoners to the public, gaining suffragists nationwide sympathy.

The Suffragist ceased publication shortly after the passage of the 19th Amendment. In 1923, it was reintroduced as Equal Rights, the official publication for the National Women’s Party.