Additional Correspondents

Choose from the list of individuals below to view biographical information. Or, scroll down to browse all additional correspondents. These individuals are represented in Katherine Anne Porter's correspondence. Biographical information highlights their their relationship to Porter.

JANICE BIALA

Janice Biala (1903-2000) was a Modernist painter, who was born in a small Polish town and emigrated to New York in 1913. She met Ford Madox Ford in Paris in 1930, and, though the two never married, they were together until Ford’s death in 1939.

Porter’s correspondence to Biala and the “Fords,” as she referred to the couple in her jointly-addressed letters, was written between 1932 and 1936, and all but one of them from Paris both before and after she married Eugene Pressley. Porter’s correspondence with Biala (and the Fords more generally) concerns financial matters, updates on her publications, friendships, and French politics, as well as her various residences in Paris.

Porter insightfully observed of herself in the January 15, 1936, letter to Biala: “But once this job is done I can be myself again, that is, entirely too sociable, too eager to please, too given to living by the minute, too fond of wasting time pleasantly……”

KAY BOYLE

Kay Boyle (1902-1992) was an American author and political activist who published over forty books, winning awards such as Guggenheim Fellowships, the O. Henry Award, and a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship. Boyle dedicated her 1940 collection, The Crazy Hunter: Three Short Novels (The Crazy Hunter, The Bridegroom's Baby, and The Big Fiddle), to Porter.

Porter wrote to Boyle of the collection, “It is a beautiful present, and the first book I ever had dedicated to me, and it may be the last if it likes, for it should be unique in all ways.”(KAP to Kay Boyle, February 14, 1940).

Boyle and Porter’s correspondence spans forty-five years, from 1931 to 1976. The two women exchanged admiration for one another, bemoaned the desperation for space and money in their literary careers, and, until their last exchange, expressed the aspiration to meet again.

JOHN MALCOLM BRINNIN

John Malcolm Brinnin (1916-1998) was a poet, critic, biographer, and scholar. Porter and Brinnin became friends when he was director (1949-1956) of the Young Men’s-Young Women’s Hebrew Association Poetry Center in New York City, where Porter was often a speaker.

In addition to six collections of poetry, Brinnin briefly edited the literary journal, Signatures, published three travelogues and biographies of Gertrude Stein, T. S. Eliot, William Carlos Williams, Dylan Thomas, and Truman Capote. Porter’s correspondence to Brinnin represented in the database was written between 1953 and 1976, with the bulk dating between 1956 and 1961.

In her April 10, 1956 letter to Brinnin, Porter observed of Ship of Fools, “Just the same, there will be a novel, though I never meant to write one, so help me! And you might say, I have done my best not to: the reasons for this obstinacy are very complicated, I may not even know all of them; but part of it is a combination of my deep feeling for the short story or short novel form and a resistance to publishers’ pressure to force you to go their way instead of your own. . . .”

CLEANTH BROOKS

Cleanth Brooks (1906-1994) was, with Robert Penn Warren, one of the founders of New Criticism. He was a Rhodes Scholar, chair of rhetoric in the English department at Yale University, and authored many works of literary criticism, including his foundational 1938 Understanding Poetry, multiple books on William Faulkner, and a collection, Modern Rhetoric, co-edited with Robert Penn Warren.

Brooks co-founded The Southern Review literary journal with Robert Penn Warren, where Porter’s “The Circus” was published in the journal’s 1935 inaugural issue. Two of Porter’s short novels subsequently published in her Pale Horse, Pale Rider (1939) first appeared in the review, “Old Mortality” (1937) and “Pale Horse, Pale Rider” (1938). Brooks and his wife, Tinkum, met Porter in 1937 and remained intimate friends throughout their lives.

Porter’s high regard for Brooks is apparent in her February 15, 1960, letter: “Yes, it is high time somebody wrote some sense about our Mr. Faulkner, pride of American literature, and you are the man for it. That is a book I want to see.” Brooks’s reflective article about his relationship with Porter. “The Woman and Artist I Knew” appeared in Katherine Anne Porter and Texas: An Uneasy Relationship (1990).

Cleanth Brooks inscribed this portrait of himself to Porter, September 7, 1972. Katherine Anne Porter Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Maryland Libraries.

TINKUM BROOKS

Edith Amy (Tinkum) Brooks (1911-1986) was one of Porter’s dearest friends for nearly fifty years and wife of Cleanth Brooks. Tinkum Brooks met her husband when he was a graduate student at Tulane University in New Orleans; they married in 1934, when Brooks was a professor of English at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

In August 1937, the Brookses met Porter when all were guests of Caroline Gordon and Allen Tate at Benfolly, their home in Clarksville, Tennessee. Porter and Tinkum Brooks forged their intimate relationship between 1938 and 1940 during Porter’s marriage to Albert Erksine, when both were living in Baton Rouge. Porter’s “Audubon’s Happy Land” records the April 1939 visit of Tinkum Brooks and Porter to the historic houses in St. Francisville, Louisiana.

The correspondence of Porter and Tinkum Brooks demonstrates their long friendship, and they discussed anything from literary gossip to recipes. Porter’s letters to Tinkum present a complex portrait grounded in female friendship, as evidenced by Porter’s July 15, 1958, letter, “I remember you in Louisiana so clearly; that was strange time wasn’t it, and I wouldn’t have a day of it back, and I wouldn’t have missed it for anything, either! I have always had just the most warm friendly feeling of attachment to you and Cleanth, and I shall always. . . . “

CAHILL SISTERS

Gertrude Cahill Beitel (1881-1959), Lily Cahill (1885-1955), and Helen Greenwell (1893-1972) were sisters and second cousins of Katherine Anne. Their mother, Virginia Myers Cahill, was the daughter of Eliza Jane Skaggs Myers, a sister of Catherine Ann Skaggs Porter, Katherine Anne’s paternal grandmother. Although they were distant cousins, Katherine Anne felt a familial bond with the sisters, corresponding with and visiting them when she could. Katherine Anne’s letters to Gertrude reveal that they kept up a regular correspondence throughout the 1950s in which she discussed Gertrude’s writing, her own writing, and thoughts about literature, social events, and their family connections. The letters written in 1955 also offer sympathy for Lily’s death and document Katherine Anne’s grief about Gertrude’s loss.

Lily Cahill, a younger sister of Gertrude Beitel, had a successful career as an actress, both on Broadway and in films. While only a few letters to Lily remain, they document Katherine Anne’s sympathy for Lily’s health ailments and her confidence that Lily was a fellow artist. Katherine Anne’s letters to Gertrude following Lily’s death in 1955 also describe what Lily meant to her.

Helen Greenwell is another of Gertrude Beitel’s younger sisters. In the archived letters to Helen Greenwell from the 1950s, Katherine Anne describes the gathering momentum of her career, reflects on childhood memories, and discusses family matters, including the decline of Gertrude Beitel’s health and her death. The letters often include greetings for Helen’s husband, Sam Greenwell, as well.

Lily Cahill, cousin of Katherine Anne Porter, New York, New York, circa May 1946. Front inscription: “For my darling/Katherine Anne/Lily.” Katherine Anne Porter Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Maryland Libraries.

MALCOLM COWLEY

Malcolm Cowley (1898-1989) was a prominent presence among the “Lost Generation,” as he lived among Stein, Hemingway, and others in France and circulated the phrase “Lost Generation.” Cowley wrote fiction, poetry, and essays, and his works include Exile’s Return, a chronicle of American literary expatriates. He also served as a translator of Gide and Valey. His work as an editor extended to his role as consulting editor at Viking Press, where he was responsible for the critical introduction to The Portable Faulkner in 1946.

Porter and Cowley met in Greenwich Village, shortly after she moved there in October 1919. Cowley and his then-wife Peggy were among Porter’s circle of friends in New York through April 1930, when Porter returned to Mexico for her last extended residence. The couple visited her in Mexico City in October 1930. Porter and Cowley’s relationship was revived at Yaddo in the 1940s. Apparently it was at Yaddo where Porter first attempted to correct Cowley’s assessment of her Mexican experiences in his Exile’s Return, originally published in 1934. Returning to that subject in 1965, Porter wrote, “It is so strange to me that my old friends, acquaintances, and colleagues, who are writing their memoirs and include some memories about me, will never consult me or ask me questions but go ahead and write their myths and mistakes” (KAP to Malcolm Cowley, March 3, 1965).

PEGGY COWLEY

Marguerite Frances Baird (1890-1970) also known as Peggy Baird or later, Peggy Cowley, was a landscape painter and mainstay of American literary and cultural circles. She was arrested with Dorothy Day in 1917 after protesting for suffrage outside of the White House, and the two were eventually pardoned by Woodrow Wilson. She was married to writer Malcolm Cowley from 1919 to 1931, when she moved to Mexico and filed for divorce. She had an affair with Hart Crane and was famously on board the ship with Crane on the day of his death. Towards the end of her life, Cowley converted to Catholicism and lived at Dorothy Day’s establishment, the Catholic Worker Farm in Tivoli, New York.

With husband, Malcolm, Peggy visited Porter in Mexico in October 1930. When she returned there in July 1931 for her divorce, Peggy Cowley joined Porter in the home she shared with Eugene Pressly and Mary Louis Doherty, until Porter and Pressly’s departure on August 21,1931. Porter’s multi-page letters to Peggy Cowley, written between December 9, 1931, and January 30, 1933, are filled with many details of her experiences and acquaintances in Berlin, Basel, and Paris. Of particular interest are Porter’s reflections on Hart Crane. “He had said so often that he would kill himself, I had begun to think he might really. I don’t know what else he could have done, he had tried so hard to destroy himself in every way short of simply ending his life at one blow.” (KAP to Peggy Cowley, January 30, 1933).

HART CRANE

Hart Crane (1899-1932) was an American poet, known for his lyric poetry. He wrote lyrics at the height of Modernism, inspired by T. S. Eliot. Crane lived as a gay man, though he was not entirely open about his sexuality due to the potential for danger that living as an openly gay man in the early twentieth century entailed. He also had an affair with Peggy Cowley – his only known heterosexual affair – shortly before his death. Crane died by suicide at the age of 32, and he has been celebrated as a leading voice of twentieth century poetry.

Porter and Crane shared the same circle of friends in Greenwich Village and became acquainted circa 1927. When Crane came to Mexico on a Guggenheim Fellowship in April 1931, he spent two weeks with Porter, Eugene Pressly, and Mary Louis Doherty in the house they shared in Mixcoac, then a separate municipality south of Mexico City. A letter Porter marked “An unsent letter June 22, 1931” outlines the events that led to the collapse of their relationship and concludes, “Your emotional hysteria is not impressive, except possibly to those little hangers-on of literature who feel your tantrums are a mark of genius. To me they do not add the least value to your poetry, and take away my last shadow of a wish to ever see you again. . . . Let me alone. This disgusting episode has already gone too far” (KAP to Hart Crane, June 22, 1931).

BARBARA THOMPSON MUEENUDDIN DAVIS

Barbara Davis (1933-2009) was a writer, journalist, two-time Puschart Prize winner, and advocate for the arts. Davis encountered Porter after covering Porter’s October 1956 reading at the Library of Congress for the Washington Post. Davis’s two pieces on Porter published in the Washington Post (November 25, 1956; October 5, 1958) led to Porter’s agreeing to extensive interviews with Davis. Porter and Davis became friends during the period that led to the publication of “Katherine Anne Porter: An Interview” in the Paris Review in 1963.

Porter was godmother to Davis’s younger son, Pakistani-American writer Daniyal Mueenuddin. The two women’s friendship was strong during Porter’s life, and Davis served as the trustee of Porter’s literary estate from 1993 to 2009, succeeding Isabel Bayley. In a letter to Davis, Porter offered advice for a woman writer: “Think for a moment of the lives of women writers worth mentioning . . . , and you will find that the conditions of being an artist for a woman are not so very different from that of a man. . . . Just work to be a good artist, and life will take care of itself.” (KAP to Barbara Thompson Mueenuddin Davis, October 11, 1958)<.

Barbara Thompson Mueenuddin Davis with her son Tamur, 1962. Katherine Anne Porter Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Maryland Libraries.

MARY LOUIS DOHERTY

Mary Louis Doherty (1896-1995) was an expatriate American who lived in Mexico for nearly seventy years of her life, working for Mexican government officials as well as for private institutions and individuals. She met Porter in Mexico City in 1921. Doherty and Porter lived together in Mexico City in 1931 and in Washington, DC, in 1944. She served as one of the models for the character of Laura in Porter's short story, "Flowering Judas."

Porter’s letters to Doherty are significant, as they chronicle her Mexican and European experiences and acquaintances. In a letter to Doherty written in 1943, Porter reflected on their time in Mexico: “Here you are, the lone survivor or friend of that incredible time and place. I never thought I would heave a sigh for the good old days, for I remember them as mostly hell, but still, I will say, must say, they had something, mysterious, indefinable, that made them better than the present, in that country and a good many others. . . . They had hope. . . .” (KAP to Mary Louis Doherty, November 1, 1943).

KENNETH DURANT

Kenneth Durant (1889-1972) was a writer and journalist. He served as the first correspondent for the American branch of Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS), a Soviet press agency, of which he served as director from 1923 to 1944. Durant was first married to Ernestine Evans, and, following their divorce, he married poet Genevieve Taggard in 1935. After Taggard’s death in 1948, Durant worked with Dartmouth College for seven years to collect and archive Taggard’s works. Porter had a cordial correspondence with Durant, and she had once been an intimate friend of Taggard.

The relationship between Porter and Durant ended on a sour note, following Porter’s discovery of Durant’s decision not to return her letters to Taggard but, instead, to restrict them from the public for twenty-five years. Porter’s characterization of her correspondence in a letter to Durant was prescient: “I have been a frightfully indiscreet letter writer, and that by the hundreds and hundreds of letters to quite hundreds of persons; all thrown off at top speed with the throttle open and the foot on the gas, if that is not mixing my machinery! and God knows I fear I may more often look like a fool than a criminal, or even just a woman of scandalous life—which, let’s face it, at intervals I was.” (KAP to Kenneth Durant, November 20, 1954).

DONALD ELDER

Donald Elder (1913-1965) was a writer and editor at Doubleday, Doran and Co., Inc., beginning in 1935; he rose through the company's ranks to become Vice President in 1946. Elder apparently met Porter at the writers’ conference at Olivet College in July 1940. A writer in his own right (his Ring Lander: A Biography was published in 1956), Elder and Porter cemented their friendship working on Eugene Pressly's translation of the Mexican novel The Itching Parrot (written by José Joaquín Fernández de Lizardi, 1816) that Doubleday published under Porter's name in 1942. The Project’s collection of their correspondence spans from 1940 to 1963, ending two years before Elder’s early death.

In one of Porter’s lively letters to Elder, she discussed the role popular magazines such as Esquire and Harper’s play in setting literary taste: “Everything they touch they turn in-to something chic, smart, fashionable, good window dressing, that is to say, vulgar. Their mission is to reduce everything to the level of the fashionable-ignorant, and I say simply they are not the ones to judge me or my work, or any one like me. . . . My life and my books are not subject to their pretensions; I have a very secure place, I have had it for a long time, it cannot be taken away from me by any one, least of all such Johnny-Jump-Ups as write ‘literary’ criticism for Esquire.” (KAP to Donald Elder, August 10, 1963).

ERNESTINE EVANS

Ernestine Evans (1889-1967) was a journalist, author, editor, and literary agent, who served in the federal government during the New Deal (Resettlement Administration) and World War II (Office of War Information). Before Evans met Porter in 1919, she had been a foreign correspondent in Europe, including Russia to cover the revolution, and was involved in the suffrage movement, writing for the organ of the National Women’s Party. In 1929, Evans authored Frescoes of Diego Rivera, a work influential in spreading Rivera's fame in the English-speaking world. Evans was married to Kenneth Durant before his marriage to Genevieve Taggard, and both were part of Porter’s circle in Greenwich Village in the 1920s.

It was through Evans, who was features editor at the Christian Science Monitor, that two of Porter’s earliest pieces on Mexico were published in 1921 and 1922. Evans may also have been directly or indirectly responsible for Porter’s early publications in Asia, Century, the Nation, and Equal Rights. Friends for more than forty years, Evans and Porter exchanged correspondence documenting their experiences and travels. One of Porter’s letters describes her approach to her Fulbright assignment in Belgium: “Yesterday, after having fairly got here, I threw off the sheepskin and revealed my true nature, teeth and claws. I announced that I was not a teacher, not even a lecturer, I was simply a working artist, and I was here to talk to them informally about how my native literature and life appeared to me, from the artist’s view: that I was not capable of doing anything else. . . . (KAP to Ernestine Evans, November 5, 1954).

FORD MADOX FORD

Ford (1873-1939) was a British novelist, editor, critic, poet, and biographer, who founded the English Review and was an editor of the Transatlantic Review. Porter met Ford in Greenwich Village in 1927, when her friend Caroline Gordon was serving as Ford’s secretary. Porter reconnected with Ford when she came to Paris in early 1932; she briefly occupied the Paris apartment that he had shared had with his companion, Janice Biala, before they went to the south of France in April 1932. Ford and Biala witnessed Porter’s marriage to Eugene Pressly on March 11, 1933, and hosted the reception that evening in their apartment.

There was frequent contact between Ford and Biala and Porter and Pressly during the period in which Pressly typed the manuscript for Ford’s It Was the Nightingale (1933). Most of Porter’s 1932-1936 correspondence with Ford is jointly addressed to Biala and ranges over various subjects, both personal and professional. In a letter addressed solely to Ford, Porter wrote, “I don’t trouble at all about my place. Writing seems to me to be my private occupation, my way of living. I want to write and I shall keep on with it, and the reputation may fall where it shall fall. I have nothing to do with it” (KAP to Ford Madox Ford, December 3, 1935).

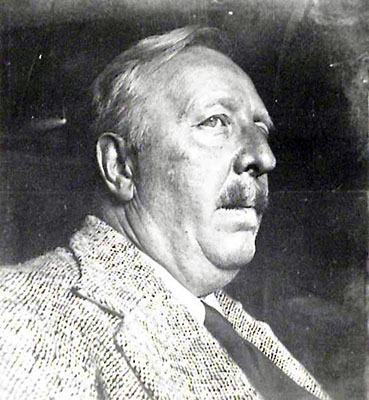

Ford Madox Ford, 1932, Basel, Switzerland. Photograph by Katherine Anne Porter. Katherine Anne Porter Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Maryland Libraries.

Caroline Gordon, 1937, Benfolly, Clarksville, TN. Katherine Anne Porter Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Maryland Libraries.

CAROLINE GORDON

Caroline Gordon (1895-1981) was a writer of short stories, novels, and criticism, winning O. Henry and Guggenheim awards. She married fellow writer Allen Tate in 1925. She is associated with the Southern Agrarian writers because of her connection to Tate and her friend Robert Penn Warren, her roots in Kentucky, and her fiction set in the South.

Gordon and Porter most likely met in 1925 when both were living in New York City, as they shared the same circle of literary friends. They became more intimate friends in 1927 when both were living at 561 Hudson Street in Greenwich Village; at the time, Gordon was serving as secretary to Ford Madox Ford. Close proximity to Gordon and Tate fostered Porter’s turn toward her Texas upbringing as a subject for her fiction, as Robert Penn Warren and Andrew Lytle, also Southern expatriates, were guests of the Tates. Porter and Gordon remained friends and supportive colleagues for many decades.

The long letter Porter wrote Gordon documenting her August to September 1931 voyage from Vera Cruz, Mexico, to Bremen, Germany, provided the materials and inspiration for Porter's only full-length novel, Ship of Fools. Porter met her fifth and last husband, Albert Erskine, at Benfolly, the home of Gordon and Tate in Clarksville, Tennessee, in August 1937. Porter’s last letter to Gordon in Porter’s papers provides insight into their long friendship: “Oh my dear, my good friend from so many years back, why am I writing all this to you who know it in your blood stream, except for the joy of talking to you about things we know and love, and just now, when we are on the eve of a great change, to set down what we felt and thought about certain things in this time of our life.” (KAP to Caroline Gordon, November 5, 1964).

WILLIAM GOYEN

William Goyen (1915-1983), editor, teacher, and author of multiple novels and short stories, was, like Porter, a native of Texas. They met in California in 1947, and Porter served as Goyen's mentor, writing a positive review of his 1950 debut, The House of Breath. Their correspondence in Porter’s papers is dated from 1950 to 1962. Porter’s letters contain literary advice but also document their affair, begun at Yaddo in January 1951. Although the affair ended by November 1951, their correspondence continued. Her letters to Goyen written in France in June-July 1952 include insightful observations on her fellow participants and the activities of the International Congress for Cultural Freedom, a month-long series of literary and artistic events in Paris.

A later letter to Goyen among Porter’s papers concludes, “With my love,” but also includes the following observation about her New York apartment, “Your nostalgia about the house in East 65th Street astounds me: I can’t imagine what for, what about. But it can’t have any connection with me, for when I lived there you certainly never showed a liking for the place. I remember it, and everything that happened there with horror, I never want to see it or think of it again. The whole thing is simply hideous to me, I can’t bear to be reminded of it.” (KAP to William Goyen, July 11, 1952).

DAVID PORTER HEINTZE and DONALD BOONE HEINTZE

David Porter Heintze (1952-) and Donald Boone Heintze (1954-) are Katherine Anne’s great nephews, the sons of her niece Ann Hollaway Heintze. Katherine Anne was charmed to be named the godmother of David, and, when David and Donald were young children, Katherine Anne often sent them postcards documenting her extensive travels and greeting cards to commemorate holidays. These frequent notes capture the warm affection Porter held for her great nephews and her desire to participate in their upbringing and education.

WALTER T. HEINTZE

Walter T. Heintze (birth and death dates unknown) was the second husband of Katherine Anne’s niece, Ann Hollaway Heintze. He was an industrial designer who emigrated to the United States from Sweden. Ann and Walter Heintze wed in 1950, and their sons David and Donald were born in 1952 and 1954. Katherine Anne often addressed Walter warmly in the family correspondence and sent him individual cards to accompany those she sent to his wife and sons. In her letters to Ann, however, Porter criticizes Walter and assures her niece she deserves better treatment.

WALTER MERRITT HEMMERLY, JR.

Walter Merritt Hemmerly, Jr. (1910-1980) was the first husband of Katherine Anne’s niece, Ann Hollaway Heintze. Ann and Walter Hemmerly were married from 1940 to 1949. They met when both were members of the San Carlo Opera. During World War II, he was a member of the armed forces and served in Europe. Katherine Anne did not correspond with him frequently, but Ann did preserve one letter Katherine Anne sent to the couple and one letter she wrote to Walter while Ann was in Europe.

JOSEPHINE HERBST

Josephine Herbst (1892-1969) was a novelist, essayist, and political activist. Porter and “Josie” shared a fascinating friendship. The two met in Greenwich Village shortly after Porter moved to Greenwich Village in late 1919. They eventually became intimate friends and confidantes and shared correspondence about their literary accomplishments and perspectives, politics, and loves. At the height of their friendship, Porter wrote to Herbst: “Josie darling, I suppose if my family and friends were celebrating my own funeral, and a letter of yours arrived in the middle, I’d rise up to read it and if possible answer it. . There’s no such thing as answering really such letters as yours, but still I love trying. . .” (KAP to Josephine Herbst, November 30, 1931). The two discussed Communist politics through the rise of the Nazis and fascism in continental Europe, as well as the bloom and then dissolution of their respective marriages.

Porter and Herbst’s relationship is a compelling study of women’s literary friendship across the twentieth century, as their letters include Porter’s plans to place reviews of Herbst’s works, strategically keeping in mind when other friends like Caroline Gordon, for example, would be publishing their own reviews. In her August 3, 1934, letter to Herbst, Porter describes her process of making use of actual experience and individuals in her fiction: “I never used anybody I ever knew or any story about anyone, complete. My device is to begin more or less with an episode from life, or with a certain character; but immediately the episode changes and the original character disappears. I cannot help it. I find it utterly impossible to make a report, as such. I like taking a certain kind of person, and inventing for him or her a set of experiences, which I feel to be characteristic, which might well have happened to that person. But they never did happen, except in the story. Or if I take one episode as a starting point, it always leads to consequences which did not occur really. I believe this is what fiction-writing really means.”

Josephine Herbst and John Herrmann, February 1929, Erwinna, PA. Katherine Anne Porter Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Maryland Libraries.

JOHN HERRMANN

John Herrmann (1900-1959) was a fiction writer and political activist. At the time he met Josephine Herbst in 1924 in Paris, he was a Communist sympathizer, but he subsequently joined the Communist Party. During the New Deal, he helped deliver classified information to the Soviet Union. It was he who introduced Whittaker Chambers to Alger Hiss in 1934.

Porter and Herbst became mutually supportive friends after Herbst and Herrmann returned from Europe in October 1924. In Summer 1926, Porter and Ernest Stock and Herbst and Herrmann rented residences in Merryall Valley, CT. Herbst and Herrmann married in September 1926, and, in early 1928, bought a home in Erwinna, Bucks County, PA. Porter stayed on a farm nearby in Summer 1928 and subsequently visited the couple in February 1929.

In a letter jointly addressed to both Herbst and Herrmann, Porter encouraged Herrmann to publish: “I hope to heavings, Mister Herrmann, that you do get down to brass tacks and do something definite for poor Ole Man Literature, who is languishing, according to some of our best critics. Don’t, Mister Herrmann, leave him languish any longer. I think your ‘Woman of Promise’ is a beautiful book, and I wish you could get it published . . . .” (KAP to Josephine Herbst and John Herrmann, February 20, 1931).

MARY ALICE "BABY" PORTER HILLENDAHL

Mary Alice Porter Hillendahl (1892-1973), most frequently called “Baby” by her family members, was Katherine Anne’s younger sister. She married Herbert Lee Townsend in 1913, but he died a year later, prior to the birth of their son, Breckenridge. She married Julius Arnold “Jules” Hillendahl in 1916.

In her letters to Baby, Katherine Anne often describes the details of her own life and discusses their immediate family members. The tone of the archived letters is generally friendly and affectionate, but Katherine Anne’s criticisms of Baby are well documented in her other family letters, especially those written to their sister Gay Porter Hollaway. The complaints Katherine Anne had long made against Baby are documented in the last remaining letter she wrote to her younger sister in 1969.

Mary Alice Hillandahl, younger sister of Katherine Anne Porter, Mission, Texas, Spring 1928. Katherine Anne Porter Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Maryland Libraries.

JULIUS "JULES" ARNOLD HILLENDAHL

Jules Hillendahl (1884-1954), also known as Kuno, married Katherine Anne’s younger sister, Mary Alice “Baby” Porter Hillendahl, in 1916. Apparently members of the Hillendahl family were friends of the Porter family, as Katherine Anne’s sisters arranged for her to stay at a Hillendahl family farm in Spring Branch outside Houston in 1913, details from which surfaced in her short story, “Holiday.” Jules/Kuno was not a frequent correspondent of Katherine Anne’s, but she sometimes included well wishes for him in her letters to Baby.

MARY ALICE HOLLAWAY

Katherine Anne was very attached to her first niece, Mary Alice Hollaway (1912-1919), born to Gay and Thomas Hollaway in 1912. Katherine Anne lived with Gay and helped to care for Mary Alice following her birth and again after the birth of Gay’s second child, Thomas. When Mary Alice died of spinal meningitis at age 6, Katherine Anne was devastated. Katherine Anne later wrote “A Christmas Story” (1946) about Mary Alice.

THOMAS H. HOLLAWAY

Thomas H. Hollaway (birth and death dates unknown) married Katherine Anne’s sister Gay Porter Hollaway in 1906, in a joint wedding with Katherine Anne and her first husband, John Koontz. He is the father of Mary Alice Hollaway (1912-1919), Thomas Harry Hollaway (1914-1951), and Ann Hollaway Heintze (1921-1987). Katherine Anne wrote her brother-in-law announcing the birth of his daughter Mary Alice. Gay eventually divorced T.H., a serial philanderer, and Katherine Anne’s disdain for him is well documented in her letters to Gay.

WILLIAM HUMPHREY

William Humphrey (1924-1997) was a novelist and short story writer who also produced works of nonfiction, including a memoir and sporting and nature stories. Like Porter, Humphrey was born in Texas, and he also left Texas in early adulthood. In 1949, Humphrey married artist Dorothy Feinman (1916-2003) and took a position at Bard College.

He was successful in getting his short stories published in the New Yorker and other mass market and literary publications, which led to the publication of The Last Husband and Other Stories in 1953. His works include his successful debut novel, Home from the Hill (1957), which was made into a motion picture in 1960, and Farther Off from Heaven (1977), the memoir that is centered on his father’s death in a car accident when Humphrey was thirteen.

Their relationship apparently foundered in the aftermath of the publication of Porter’s Collected Essays and Occasional Writings, as she resented her publisher’s recognition of the “help and guidance” of Humphrey and others in its publication. Porter’s correspondence to the Humphreys includes postcards and holiday greetings to both but primarily consists of her letters to Humphrey filled with discussions of their work and other literary topics. A recurring subject is Porter’s struggle to complete Ship of Fools: “Me, I am afraid I am not living up to my own rules very well—I am drawing out this book too long. (Maybe! How can I tell? It all seems to want to be written!) but maybe I told you, it began as the fourth of the four projected short novels, oh God, how I wish people wouldn’t call them novelettes or worse, novellas—and it simply got away from me, determined to be a long book, and so it will be, and soon, I hope.” (KAP to William Humphrey, February 14, 1958).

MARIANNE MOORE

Marianne Moore (1887-1972) was an influential Modernist poet whose work merited numerous awards, including the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, and the National Medal for Literature. Moore was the editor of the literary magazine The Dial, which published work from William Carlos Williams, Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, and Gertrude Stein during her tenure from 1925 to 1929.

Porter and Moore most likely met in the 1950s when Porter returned to New York from California. From Porter’s letters to Moore, it is clear that Monroe Wheeler and George Platt Lynes were friends to both women. Porter’s admiration for Moore’s poetry is clear in Porter’s letter acknowledging Moore’s gift of Like a Bulwark: “Oh what fine spare athletic noble poetry it is—some of your very best things are here; you are a better poet than you were, even.” (KAP to Marianne Moore, January 1, 1957).

Katherine Anne Porter and Flannery O’Connor, April 1958, Milledgeville, GA. Katherine Anne Porter Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Maryland Libraries.

FLANNERY O'CONNOR

Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964) was a renowned American writer, known for her Southern Gothic fiction, notably her short stories, including the infamous “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” Porter and O’Connor met initially at O’Connor’s Georgia home in April 1958, where Porter encountered O’Connor’s peacocks. Both also participated in a panel on recent Southern fiction at Wesleyan College, Macon, Georgia, in October 1960.

Porter recalled her impressions of O’Connor in a letter to Caroline Gordon: “Flannery I saw on exactly three days, rather spaced if I remember, and the impression she made upon me is all I can tell about. I have really no idea what she thought or felt about me, and except it was courteous and gentle, as she was in everything she did that I saw: and I believe and always have believed that she was a genius if I ever saw one, and the profundity of her vision of the world and its relation to eternity is mysterious and almost appalling. . . .” (KAP to Caroline Gordon, November 5, 1964).

O'Connor and Porter expressed appreciation for each other’s literary gifts directly via their correspondence. In her August 12, 1963, letter to O’Connor, Porter recounted the reply of a French bookseller to her question about the sale of O’ Connor’s books, “And he said, ‘Very nicely, nothing sensational, it is just that she has her readers!’ And Flannery, I glowed with pleasure, for what honest artist could ask for more? And I know, because from my first book I had my readers, and I still have them, and my unchanging affection for them and delight in them; I never expected or wanted more. . . .”

DOROTHY RAE PORTER PARRISH

Dorothy Rae Porter Parrish (1918-1997) is the first of Paul Porter, Sr., and Connie Porter’s four children was a niece of Katherine Anne. Katherine Anne’s single surviving letter to Dorothy thanks her for the fresh moss she sent to decorate the nativity nephew Paul was making for her.

BRECKENRIDGE PORTER, SR.

Breckenridge Porter, Sr. (1914- 1999), was the only child born to Katherine Anne’s younger sister, Mary Alice “Baby” Porter Hillendahl. Breckenridge’s father, Herbert Lee Townsend, died before he was born. Katherine Anne visited Baby to help care for her and her son after his birth. Breckenridge was later adopted by Katherine Anne’s brother, Paul Porter, Sr. Katherine Anne’s 15 April 1930 letter mentions her sisters and asks sixteen-year-old Breckenridge to write to her.

CONSTANCE EVE INGALLS "CONNIE" PORTER

Connie Porter (1892-1971) was the wife of Porter’s brother, [Harrison] Paul Porter, Sr., and the mother of [Harrison] Paul Porter, Jr., and his three siblings. In the only remaining letter Katherine Anne wrote to Connie, she discusses works of Durer and her health as well as her regret about having been unable to attend the wedding of Charles Boone Porter, Connie and Paul Sr.’s younger son.

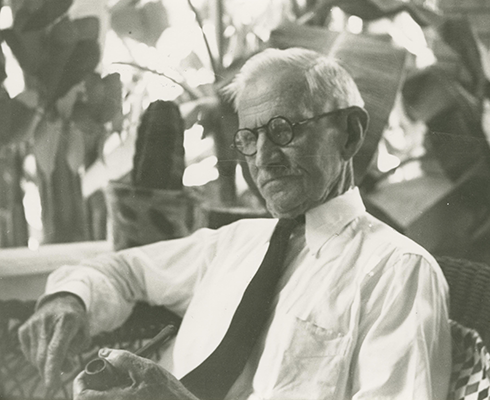

Harrison Boone Porter, father of Katherine Anne Porter, seated in a wicker chair dressed in shirt and tie, Texas, circa June-July 1937. Katherine Anne Porter Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Maryland Libraries.

HARRISON BOONE PORTER

Harrison Boone Porter (1857-1942), the father of Katherine Anne, married Mary Alice Jones Porter in 1883. In addition to Katherine Anne (1890-1980), Harrison and Mary Alice had four other children: Gay (1885-1969), Paul (1887-1955), Johnnie (1889-1890), and Mary Alice “Baby” (1892-1973). When his wife Mary Alice died in 1892, Harrison moved his family from Indian Creek, TX, to the home of his mother, Catherine Ann Skaggs Porter, in Kyle, TX, and relied upon her help to care for the children. Harrison read widely and worked as a teacher for a period of time. He also worked for a railroad, as a salesman, and as a farmer.

Katherine Anne’s archived letters to her father are often long, warm and affectionate in tone, and give detailed accounts of her recent experiences. At times Katherine Anne was anxious for his approval, and at other times she could be exacting in her criticisms of his shortcomings, especially in her letters to Gay.

IONE FUNCHESS PORTER

Ione Funchess Porter (circa 1880-1953) was Katherine Anne’s aunt by marriage to Newell Porter, the brother of Katherine Anne’s father, Harrison. Katherine Anne’s partial draft of a 1933 letter to “Tante Ione” shares fond recollections of her aunt, discusses family history, and provides updates on her life and work.

[HARRISON] PAUL PORTER, SR.

Born Harry Ray Porter before changing his name, Harrison Paul Porter, Sr. (1887-1955), was Katherine Anne’s older brother. He and his wife Connie had four children: Dorothy Rae Porter Parrish (1918-1997), Constance Elita “Patsy/Pat” Porter McClughan (1925-1996), Charles Boone Porter (1933-), and Katherine Anne’s beloved nephew, Paul Porter, Jr.

In the only surviving letter to her brother, written in 1932, Katherine Anne describes her life in Paris and her marriage to Eugene Pressly.

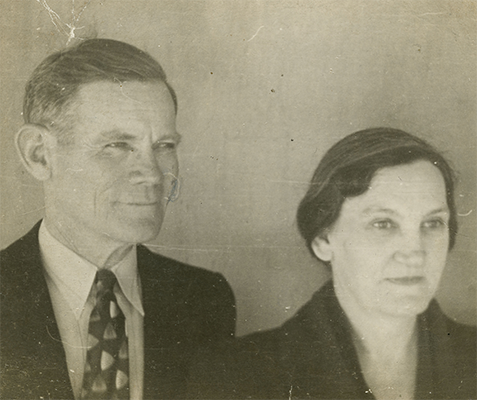

Paul Porter, Sr., brother of Katherine Anne Porter, and his wife Constance Eve Ingalls Porter, at the time of the marriage of their daughter Constance Elita, who was known as Pat, Houston, Texas, July 1942. Back inscription: “When Patricia was married.” Katherine Anne Porter Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Maryland Libraries.

LEO PORTER

Leo Porter (1887-1970), a first cousin of Katherine Anne, was the son of her father’s brother Alpha Porter. When Leo wrote her after the success of Ship of Fools, Katherine Anne responded to inquire about his life and to discuss their shared family history.

CORA ADDISON POSEY

Cora Addison Posey (1869-1963) was an Indian Creek friend of Katherine Anne’s mother, Mary Alice Jones Porter. Katherine Anne writes “Miss Cora” about memories of her from childhood, about the family letters that Cora returned to Katherine Anne and her siblings, and about her work.

EZRA POUND

Ezra Pound (1885-1972) was a Modernist American poet, often associated with T. S. Eliot as a canonical representative of Modernist expatriate poetry. Pound was part of the Imagist movement and expressed intense devotion to style and aesthetics. He also expressed support for fascist European government leaders during his time in Italy and faced imprisonment for his views following the second World War. Porter was one of Pound’s supporters after he was awarded the first Bollingen Prize in 1949; the resulting controversy led to an investigation into the prize committee.

The correspondence between Porter and Pound was prompted by Porter’s sending a copy of The Days Before to Pound in September 1952. His letter in response took issue with her review of The Letters of Ezra Pound, 1907-1941, reprinted in the volume. Porter subsequently visited Pound at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, DC, in March 1953. In Porter’s October 21, 1952, response to Pound’s critique of her review, she expressed her admiration: “Still, I must even now say one thing: I have known your work, and loved and respected it, for more than thirty years: and did not in the beginning need any one to tell me what to think about it: you came just at the right moment for a lot of us, and so many of us discovered you each one for himself.”

THEODORE ROETHKE

Theodore Roethke (1908-1963) was an American poet born and raised in Michigan. Roethke is one of the most influential poets of the twentieth century, given the long list of his former students who became successful poets in their own right. He married Beatrice O’Connell, a former student, in 1953 and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1954 for The Waking. Porter and Roethke apparently met at the Olivet College Writers Conference in Summer 1937. From evidence in Porter’s correspondence with Roethke’s wife, it appears that Roethke also entertained Porter in University Park at some time during the time he taught at Pennsylvania State University (1936-1943, 1947).

The only Porter letter to Roethke in her papers is a transcript of a letter she wrote to him on March 10, 1941. In the letter, she responded to his of March 7, which had been enclosed with a copy of his first volume of poetry, Open House. “There is this about us, dear Ted: No matter what happens, we have no place to run to, here and now we must make our stand and see things through. I for one am most grateful for this: we must put an end to this flight of the human race before the spectre of its own evils, from the consequences of its own weaknesses and complicity in world guilt. Here we must live and die; and we none of us can escape the responsibility of what life is in this place shall become.” The remaining Porter letters in the Roethke file were written, in 1965, to his wife who was gathering his letters for posthumous publication.

EDITH SITWELL

Edith Sitwell (1887-1964) was a British writer, poet, and critic famous for her eccentric poetry, including famous verses like her World War II poem “Still Falls the Rain,” about the London Blitz. Sitwell was a member of an aristocratic family, and she and her writer brothers, Oswald and Sacheverell, were famously active critics of art and literature. Porter’s admiring review (New York Times, September 25, 1949) of Edith Sitwell’s Canticle of the Rose (1949) initiated their relationship. In January 1950, Sitwell wrote Porter thanking her and expressing admiration for Porter’s work. They corresponded for the remainder of Sitwell’s life and met at least once in New York City.

Porter was delighted to receive an inscribed copy of Sitwell’s Collected Poems (1954) and especially charmed that one poem, “A Sylph’s Song,” was dedicated to her: “The splendid Collected Poems came to me in Liege at a moment of the utmost darkness, the morning star suddenly shining through the cold and murk of that dullest of towns, and my long slow giving way to illness. So imagine! The book would have been enough, but your inscription and above all the dedicated poem, —such a gift would make happiness happier, but in that special time it worked miracles of healing! And my little song—I’ll never believe it is not one of your diviner lyrics—delights me to the heart. . you could never have chosen one for me that I could like better and altogether, it was a gay surprise: I had never dreamed of such a thing. So bless you forever!” (KAP to Edith Sitwell, March 24, 1955).

WILLIAM JAY SMITH

Primarily remembered as a poet, William Jay Smith (1918-2015) had a career that included creative writing, translation, academia, and politics. Smith served a two-year term in the Vermont House of Representative, from 1960 to 1962, and also served as a poetry consultant to the Library of Congress from 1968 to 1970. Institutions at which he taught or served as poet in residence included Williams College, Columbia University, and Hollins College. Porter and Smith met at a University of Connecticut writers conference in summer 1953. The file of Porter-Smith correspondence, which spans the period from 1955 to 1978, includes letters from Smith as well as from his two wives, poet Barbara Howes Smith (married 1947-1965) and Sonja Haussmann Smith (married 1966).

Porter and Smith socialized often during 1964-1965 when he was in residence in Washington, DC, at Arena Stage on a Ford Foundation grant and during his tenure as poetry consultant. Evidence of both their renewed friendship and his admiration for Porter is the poetic tribute he wrote for Porter’s birthday: "A Rose for Katherine Anne Porter On her Seventy-fifth Birthday, 15 May 1965." In their correspondence, Smith and Porter shared news on literary projects, travel, common friends and health. The last of Porter’s letters in the file is valedictory: “As I look back I see my themes have not been particularly merry, but then, I have not found this life or world particularly merry. Funny sometimes, amusing now and then, grotesque, brutal, beastly, ugly as the devil and sometimes so brilliant and joyous I have hardly been able to take it after all the evil I have witnessed and suffered from.” (KAP to William Jay Smith, February 8, 1977).

DELAFIELD DAY SPIER

Grace Delafield Day Spier (1901-1980) was a political activist, before devoting her life to her husband and children. Della, the name by which Spier was known throughout her life, was the younger sister of Dorothy Day, who is best known for her role in the Catholic Worker Movement. Before her 1928 marriage to Franklin Spier, founder of an advertising agency for the publishing trade, Della Day worked for the Fellowship for Reconciliation, a Quaker organization, and Margaret Sanger and became an apostle spreading the gospel of birth control. It was through her sister Dorothy that Della connected with the literary circles of Greenwich Village, where she met Porter sometime after 1925. Della and Porter became fast friends. In August 1927, they were among those who demonstrated in Boston prior to the executions of Sacco and Vanzetti. In early March 1929, Porter joined a group of four expatriate New Yorkers vacationing in Bermuda, two of whom were Della and Franklin Spier. After the Spiers departed Bermuda in mid-March, Porter wrote Della frequently.

Porter’s letters to Della included in the Project range over many topics, their common friends, music, Porter’s progress on her biography of Cotton Mather, reviews of Flowering Judas, her changing view of Mexico as well as intimate personal subjects. One of the very few references in all of Porter’s correspondence to the stillbirth that Porter experienced in 1924 appears in her February 17, 1931, letter to Della. In it, Porter reacted to the news that Della was expecting a second child: “It was lovely news and it is even better to know you have changed your doctor, and will have decent care. I know Dr. Mary—she was called in to look me over after I came home from the midwife, after the still-birth, and she came in wearing a tomato red coat and hat, and was the merriest sight a sick-room could behold.”

JAMES STERN

James Stern (1904-1993) was an Anglo-Irish writer whose work encompassed short stories, non-fiction, book reviews, and translations. Born in County Meath, Ireland, he met and married his German wife Tania Kurella in 1935, while living in Paris after residences in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), London, and Frankfurt. The Sterns lived in New York City for about a decade, beginning in 1939. The remainder of their lives, the couple lived in south west England. Together they translated the works of German authors including Thomas Mann, Franz Kafka, and Bertolt Brecht. In 1933, Stern sent Porter a copy of his first short story collection, The Heartless Land (1932), when both were living in Paris. They began a friendship that endured for the remainder of Porter’s life and came to include his wife.

Although their correspondence stretched from 1933 to 1977, few of Porter’s letters to Stern are in the file of their correspondence in Porter’s papers. The bulk of those letters were written in Europe after the publication of Ship of Fools and include discussion of her travels, common friends and acquaintances, and health. Many of the letters are concerned with the anthology of short stories Porter had been contracted to complete. In her July 23, 1963, letter to Stern, Porter wrote an insightful self-assessment: “I write so cheerfully and energetically on anything I thought up for myself, and so long as I haven’t promised to finish it for any magazine: and the minute I do promise, I fall into a catatonic state vis-à-vis that work, abandon it and go do something else that nobody is trying to get away from me! Jimmy, this must be something awful in my past, and I don’t care, and I’m glad I don’t know, and I’ve got simply hundreds of the most idiotic inhibitions and complexes, and I have earned them all honestly and I need them, and I enjoy them, and they certainly do help my work.”

GENEVIEVE TAGGARD

Genevieve Taggard (1894-1948) was an accomplished poet, who lived and worked in Greenwich Village at the beginning of her career, after earning her B.A. from University of California, Berkeley, in 1919. With Maxwell Anderson, she founded Measure: A Journal of Poetry in 1921. Her first marriage in 1921 to Robert Wolf produced a daughter, Marcia, but ended in divorce in 1934. She married Kenneth Durant in 1935. Between 1929 and 1947, she held teaching positions at Mount Holyoke College, Bennington College, and Sarah Lawrence College. Taggard was involved in socialist circles throughout her career, and she served as contributing editor for the socialist magazine New Masses. In addition to her many collections of poetry, Taggard also wrote a biography of Emily Dickinson, The Life and Mind of Emily Dickinson (1930).

Porter’s early correspondence to Taggard concerns poems Porter submitted to Measure. Porter’s letters to Taggard are both professional and intimately personal. Porter trusted Taggard with the story of her pregnancy that ended in stillbirth in 1924. She also shared accounts of her life with Ernest Stock at Taggard and Wolf’s Connecticut farm in summer 1926. The friends reconnected after Porter returned from Europe in late 1936.

During her tenure teaching at Sarah Lawrence College, Taggard taught Porter’s work, to which Porter wrote: “You can imagine how it pleases me that your freshmen are reading my story, and I shall have others soon, and I hope they will like reading them, too. I love the young ones, and believe in them, mystically, perhaps, but I still hope. This summer I lectured and taught for the Conference at Olivet, and am going back next year. It was an odd experience, and I felt rather a fraud, but the kind of fraud I don’t mind being really, because I really felt I had something to say, and only failed to say it as well as I might have. . . .” (KAP to Genevieve Taggard, October 28, 1937).

Allen Tate, circa 1937, Benfolly, Clarksville, TN. Katherine Anne Porter Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Maryland Libraries.

ALLEN TATE

Allen Tate (1899-1979), a significant literary man of letters in the first half of the twentieth century, was a poet, critic, biographer, novelist, editor, and teacher. One of the “Fugitives” at Vanderbilt University as an undergraduate, Tate, a native of Kentucky, is often associated with the Southern Agrarians but also with New Criticism. During his lifetime, he received many awards and fellowships. He was Poetry Consultant at the Library of Congress from 1943 to 1944. The longest tenure among his teaching positions was at the University of Minnesota, where he served from 1951 to 1968. Tate had a troubled relationship with Caroline Gordon, as the two married, divorced, remarried and divorced again.

It is likely that Porter met Tate in Greenwich Village in 1925, as they were members of the same literary circle. As Caroline Gordon became one of Porter’s intimate friends, Tate and Porter also developed an enduring relationship. Tate and Gordon arranged for Porter’s first invitation to the Olivet College Writers Conference in Summer 1937, after which Porter joined the couple at Benfolly, their home in Clarksville, TN. During that visit, Porter met Albert Erskine, who was to become her fifth husband.

It was also through Tate’s intervention that Porter was appointed to fill the position of Fellow of Regional American Literature at the Library of Congress in 1944. During his tenure as editor of Sewanee Review, Tate published the first excerpt from the novel that became Ship of Fools. Porter and Tate were also members of the American delegation to the International Congress for Cultural Freedom held in Paris in 1952. In their correspondence, Porter and Tate exchanged literary gossip, commented on each other’s work, and discussed their personal lives. In the aftermath of the publication of Ship of Fools, Porter wrote: “My novel is a mystery to me, too; I don’t quite know how I did it, I only know what I was aiming for, meant to do. It is astounding the long gamut from extreme admiration, belief, to extreme hatred and even personal insult the critics and reviewers have run, waving laurel wreaths and flourishing butcher’s cleavers as they go.” (KAP to Allen Tate, November 21, 1962).

EUDORA WELTY

Eudora Welty (1909-2001) was an American writer whose oeuvre includes short stories, novels, essays, a best-selling autobiography, and photographs. Born in Jackson, MS, where she lived most of her life, Welty set her fiction primarily in the South. During her lifetime, Welty garnered numerous honorary degrees, fellowships, and awards. Porter and Welty met in Baton Rouge in 1939, when Porter was married to Albert Erskine.

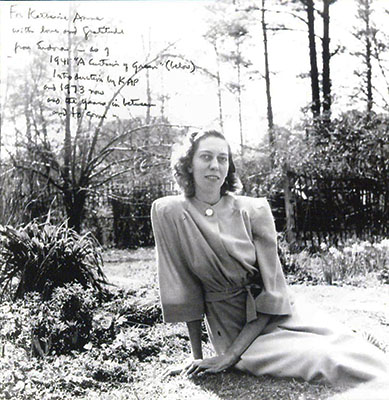

Porter was a mentor to Welty early in her career, and the two became close friends when they were assigned the same lodging at Yaddo in Summer 1941. Porter wrote the introduction to Welty’s first collection of short stories, A Curtain of Green (1941). Although Porter often expressed regret that she and Welty did not see each other more often, Porter did enjoy a stay in Jackson with Welty and her mother in March 1952. Welty also participated in the short-lived Katherine Anne Porter Foundation (1967-1973), established to support creative writers. It is also telling that Porter was chosen to present Welty the Gold Medal for Fiction of the National Institute of Arts and Letters in May 1972.

In 1990, Welty wrote about her relationship with Porter and how their time at Yaddo began their friendship: “a long life of correspondence started between us, easygoing and as the spirit moved us—about reading, recipes, anxieties and aspirations, garden seeds and gossip” (Georgia Review, vol. 44, no. 25, Spring/Summer 1990). The two women maintained a lifelong friendship, buoyed by their wide-ranging correspondence, though the two often shared their thoughts about regionalism, the literary marketplace for women, and the challenge of writing about the work of friends: “Maybe we are wrong to be uneasy about writing about the friends whose work we like. I love to praise what I love, and I don’t for a minute believe that love is blind—indeed, it gives clearness without sharpness, and surely that is the best light in which to look at anything.” (KAP to Eudora Welty, April 15, 1952).

Eudora Welty, 1941, Jackson, MS. Katherine Anne Porter Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Maryland Libraries.

Barbara Harrison Wescott and Monroe Wheeler, Spring 1934, Davos, Switzerland. Katherine Anne Porter Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Maryland Libraries.

BARBARA HARRISON WESCOTT

Barbara Harrison Wescott (1904-1977) was a publisher and philanthropist. Her father, Francis Burton Harrison, served as a U. S. Congressman and was subsequently appointed Governor-General of the Philippines during the administration of Woodrow Wilson. Her mother, Mary Crocker, a railroad and banking heiress, died in an automobile accident when Barbara Harrison was a young child. By 1928, when Glenway Wescott and Monroe Wheeler met her, the inheritance from her mother had enabled her to purchase and furnish an apartment in Paris and a country place outside of Paris. She and Monroe Wheeler founded the fine press Harrison of Paris in 1930. Shortly after the press ceased publishing in 1934, Barbara Harrison met Glenway Wescott’s younger brother, Lloyd, and they married in April 1935. Barbara and Lloyd Wescott purchased a farm estate in western New Jersey, where pioneering work in the artificial insemination of dairy cows was conducted. Both Barbara and Lloyd Wescott were philanthropists of various civic, cultural, and scholarly causes throughout their married life.

Porter’s friendship with Barbara Harrison grew from their work on Katherine Anne Porter’s French Song-book (1933). Porter often socialized with her and Glenway Wescott, Monroe Wheeler, and George Platt Lynes in Paris from late 1932, when she returned from Basel, until 1934-1935, when the others relocated to the United States. The warm friendship between the two women was forged when Barbara Harrison financed Porter’s month’s stay at Park Sanitorium in Davosplatz, Switzerland, with herself and Monroe Wheeler in Spring 1934. Porter also enjoyed Harrison’s generosity on a trip to Salzburg and Munich in summer 1934. Barbara Harrison Wescott continued to provide emotional and financial support to Porter until the publication of Ship of Fools in 1962. Porter expressed her gratitude for her friendship and support with the dedication to the novel: “For Barbara Wescott/ 1932: Paris, Rambouillet, Davosplatz, Salzburg, Munich, New York, Mulhocaway, Rosemont: 1962.”

Porter’s letters to Barbara Wescott cover a wide variety of topics including music, books, health, common friends, and Porter’s struggles to complete Ship of Fools. Porter and Barbara Wescott remained dear friends until the latter’s death in 1977. Reflecting on their friendship, Porter wrote, “You have been a source of good luck and good fortune and strength to every one who ever came near you, I do believe, and I hope in your perfect goodness you will not mind my praising you to your face, as a kind of anniversary remembrance, and something surely to be said at least once in a life time between friends.” (KAP to Barbara Harrison Wescott, March 9, 1941).

TENNESSEE WILLIAMS

Tennessee Williams (1911-1983) was an American playwright, best known for his popular dramas, A Streetcar Named Desire and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. The Correspondence Project holds one letter from Porter to Williams, in which Porter expresses gratitude for Williams’s positive review of the Broadway production of Pale Horse, Pale Rider. Porter writes, “What I have always liked best about you is the boldness and obstinacy (please understand that for me that’s a good word for an admirable trait) with which you stand by your point of view.” (KAP to Tennessee Williams, January 25, 1958).

SALLIE CRAWFORD WILLSON

Sallie Crawford Willson (1889-1978) was the daughter of Loula Andrews Crawford, who was an Indian Creek friend and music student of Porter's mother. Katherine Anne responded to a letter from her in 1965 to describe her life and her family members.