Battle of Bladensburg

"Here - fought Commodore Barney,

so nobly and so gallantly,

Against Britain's sons and slavery,

For a fighting man was he!

-

There - did General Winder flee,

His infantry and cavalry,

(Disgracing the cause of liberty),

For a writing man was he!"- Inscription reportedly found by a visitor to the battlefield, 1819.

Portrait of Joshua Barney, 1759-1818. By Rembrandt Peale. Ca. 1817.

Whether the blame for the American defeat at Bladensburg rests primarily with the performance of the militia who faced the British regulars or the actions of inept commanders, the Battle of Bladensburg on August 24, 1814 led to the capture of Washington and the burning of government buildings in the capital city. Antiwar newspaper editors seeking to assign blame to President Madison's administration, derisively dubbed the battle the Bladensburg Races. National honor was restored three weeks later when the British were repulsed in Baltimore. The earlier humiliation at Bladensburg gradually receded from the historical memory of most Americans.

The story of the Battle of Bladensburg has many fascinating aspects.

- The British used this new technology to unnerve the Americans.

- Colonial Marines. Escaped slaves from the Chesapeake region enlisted with the British and fought with distinction at the battle.

- Joshua Barney's Bargemen. African Americans also served on the American side as members of Commodore Barney's flotilla force, which provided artillery support during the battle. British commanders noted the effectiveness of Barney's unit.

- James Madison. The President witnessed the British attack after he was nearly captured reviewing the American positions prior to the battle.

- Military Field Hospitals in Bladensburg. British and American wounded were treated, primarily by local doctors, in the town. One of these medical men, William Beanes of Upper Marlboro, was central to the story of the composition of the "Star Spangled Banner."

One eye witness who served with Barney, perhaps best summarized the affair, when he wrote:

"If the militia regiments, that lay upon our right and left, could have been brought to charge the British, in close fight, as they crossed the bridge, we should have killed or taken the whole of them in a short time; but the militia ran like sheep chased by dogs."- Charles Ball, 1837.

Diorama of Battle of Bladensburg.

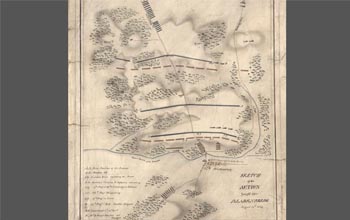

"Sketch of the action near Bladensberg [i.e. Bladensburg], Augus 24th" By Thomas Ormsby, 1816. Library of Congress

Sketch of Robert Ross, 1766-1814 by an unidentified artist. Ca 1815.

Witnesses to the Battle: the Calverts of Riversdale

Riversdale House Museum, Photo by Douglas McElrath.

George and Rosalie Calvert lived at the Riversdale plantation, located just north of Bladensburg off the Baltimore turnpike. The grand residence at Riversdale was planned by Rosalie’s father, Henri Stier, a Belgian nobleman who brought his family to the United States to escape Napoleon’s invasion of the Low Countries. After Stier returned to Europe in 1805, his daughter and son-in-law completed the building project. Riversdale was at the center of an extensive estate and is an example of the interest of moneyed investors in the Bladensburg region.

In August 1814, Rosalie Calvert described the British invasion of Prince George’s County as creating a “state of continual alarm.” She and her family could see the cannon balls and feel the artillery fire at the Battle of Bladensburg. In the aftermath, the Calverts visited the town and became acquainted with some of the British officers convalescing from wounds. They became good friend with the British agent for the exchange of prisoners, Colonel Thomas Barclay, who was living at Bostwick in Bladensburg and offered to forward letters to Rosalie’s family in Europe.