Scandal and Hope

“Desolation was Bladensburg to look at, and low-lived wickedness to know.”-George Alfred Townsend, 1873

Manufacturing in an Early Federal Town

Bladensburg's decline after the economic panic of 1819 was rapid and long lasting. By the 1830s a traveler described the town as a "wretched, decayed village on the Eastern Branch." Its once fashionable inns and taverns, now became the haunts of drunkards, gamblers, and worse. Murders, riots by railroad workers, and financial peccadilloes often were the themes of newspaper stories about Bladensburg. Reflecting the racist attitudes of the time, the town was regarded as a place where illicit activities, such as cock fighting, caused a promiscuous intermingling of black and white residents.

Yet in this image of a community gone to seed, there were hopeful signs. In the 1850s and 60s, a school for young women operated just to the north of town, and prominent individuals living in Bladensburg included William Pinkney, Bishop of the Protestant Episcopal Church in Maryland. Soldiers stationed in the nearby defensive works protecting Washington during the Civil War found the town quaint and the waters of its spa refreshing. In the aftermath of the war, local African Americans supported a school, churches and the emergence of a black town in North Brentwood.

Bladensburg in 1912

The centennial of the War of 1812 was the occasion for publications that included images of Bladensburg. In this scene from a biography of Joshua Barney, Main Street (Alt. Route 1 today) appears to have changed little in the century since the battle.

William Frederick Adams. Commodore Joshua Barney. Springfield, Massachusetts: Privately Published, 1912. MD E353.1 .B26A2 1912

The Parthenon

“The author of “Parthenon” has been lately represented in the Pan-Electric controversy, as an ignorant and vulgar person, but the following extracts, which we take from his New York publisher’s notice appended to the second edition of his “Greek Slave,” will indicate that his political enemies have, perhaps, underrated him.”- Publisher’s Notice, Parthenon 1886.

Built in the 18th century, the Parthenon occupied a prime location on the heights overlooking Bladensburg. In the 1880s it was the base of operations for the Rogers family whose Pan-Electric Telephone Company briefly challenged Alexander Graham Bell on the validity of his patents for the telephone. The father-son team of James Webb Rogers and J. Harris Rogers championed their case, but the elder Rogers’ aggressive courtship of Washington politicians led to charges of bribery, corruption, law suits, and eventually a congressional investigation.

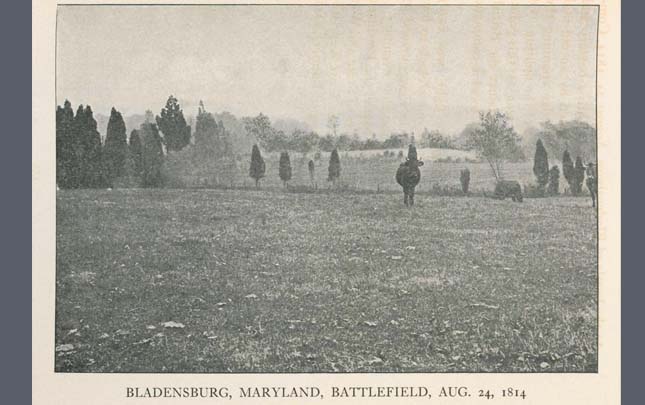

The celebrated cartoonist Thomas Nast lampooned members of President Grover Cleveland’s political circle during the scandal. In this cover of Harper’s Weekly, Nast shows Attorney General Garland ensnared while the symbols of justice lie broken at his feet.

According to the New York Times, the symbolism in the image consists of the following:

“Cartoonist Thomas Nast plays on the attorney general’s name by drawing a garland, which has slipped from his brow to his eyes, blinding him to the evil intentions of the Pan-Electric Telephone Company. The telephone cord he holds is a snake, while the smiling telephone box is topped by demonic horns. The telephone is marked with “influence” and “stock,” and the fishing net beside Garland is filled with “stock.” For the artist, the attorney general’s notion of justice is fishy: fish heads appear on the symbolic sword (which is broken) and scales of justice.”

However, James Webb Rogers was not just a lawyer who aided his son during the Pan-Electric Scandal, he was also a writer. He published several pamphlets of poetry, one titled “Parthenon,” which seemed to be popular around the time of its publication as some evidence has suggested. In the beginning of the 1886 edition, however, the publisher (who may have been Rogers himself) mentions the Pan-Electric Scandal and politely, yet pointedly, defends the author’s reputation, as shown above.

Later in the 20th century, a murder at the Parthenon further darkened its reputation. A shooting fueled by gang warfare erupted inside the “Old Colonial Tea House,” as it was then called, killing one and injuring many. During the murder investigation, the authorities discovered that the house served as a brothel that was part of a prostitution ring that spanned the East Coast. It was such a huge discovery that J. Edgar Hoover cited it as a case study in his report on “The White Slave Trade” (pg 481)

Parthenon Manor and the Pan-Electric Scandal

Built in the 18th century, the Parthenon occupied a prime location on the heights overlooking Bladensburg. In the 1880s it was the base of operations for the Rogers family whose Pan-Electric Telephone Company briefly challenged Alexander Graham Bell on the validity of his patents for the telephone. The father-son team of James Webb Rogers and J. Harris Rogers championed their case, but the elder Rogers’ aggressive courtship of Washington politicians led to charges of bribery, corruption, law suits, and eventually a congressional investigation.

The celebrated cartoonist Thomas Nast lampooned members of President Grover Cleveland’s political circle during the scandal. In this cover of Harper’s Weekly, Nast shows Attorney General Garland ensnared while the symbols of justice lie broken at his feet. Later in the 20th century, a murder at the Parthenon further darkened its reputation. The house was demolished to make way for a shopping center in the 1940s.

Private Collection. Harper’s Weekly, February 13, 1886.

Murder at the Parthenon

In Depression-era Bladensburg, Parthenon Manor was known as the Colonial Tea House. This innocuous name hid a more sinister purpose. In reality it was a house of prostitution, and a dispute between rival gangsters led to a murder in November 1931. This Baltimore Sun photograph of the house was published as the shooting evolved into a multi-state vice investigation by the FBI.

Private Collection, Baltimore Sun, November 27, 1931