Washington, D.C. was a troubled place in the 1970s, but there were reasons for hope. The corrosive effects of the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal, systemic racism, damages from civil unrest, and bureaucratic mismanagement had inflicted undeniable wounds on the city. Despite this, when the United States Congress—previously the sole governing authority of the Federal District—granted “home rule” in December 1973, DC residents were finally permitted to democratically choose a mayor and city council. Civil rights activist and DC city council member Marion Barry’s victorious mayoral campaign over incumbent Walter Washington in late 1978 particularly ushered in a “sense of hope, optimism, and possibility that many DC residents embraced,” according to historians Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove. “[Barry’s] rise from sharecropper’s son to street protester to chief executive of the nation’s capital inspired many Washingtonians to think grandly about making DC a model Chocolate City.”1

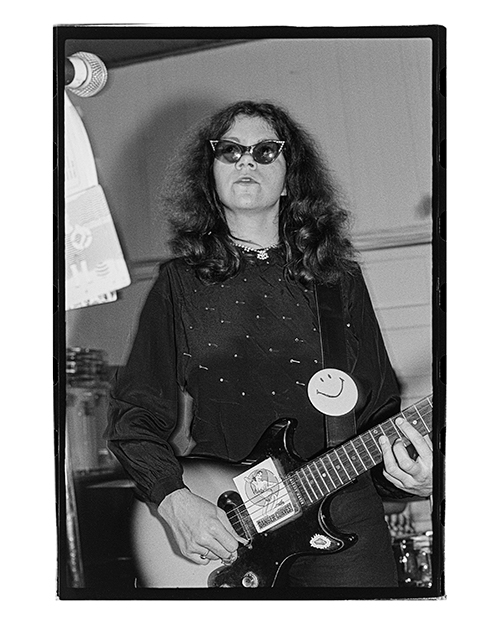

Culturally, DC continued its long history of music excellence and innovation in the 1970s. In addition to thriving jazz, folk, rock, R&B, and bluegrass communities, two new genres developed in this decade that would each become synonymous, for many, with the city itself. Go-go—a galvanic hybrid of funk, hip hop, and Afro-Caribbean musical influences—was led by genre trailblazers like Chuck Brown, Experience Unlimited, and Trouble Funk. The powerful sense of community and self-sufficiency at the core of go-go was echoed in the other emergent genre from this period: Punk rock.

...

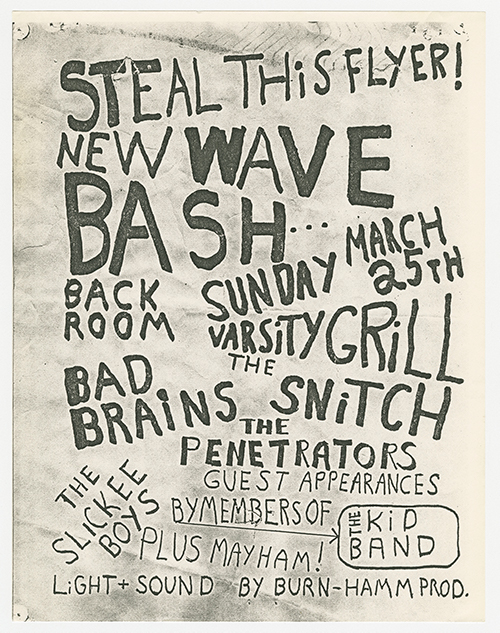

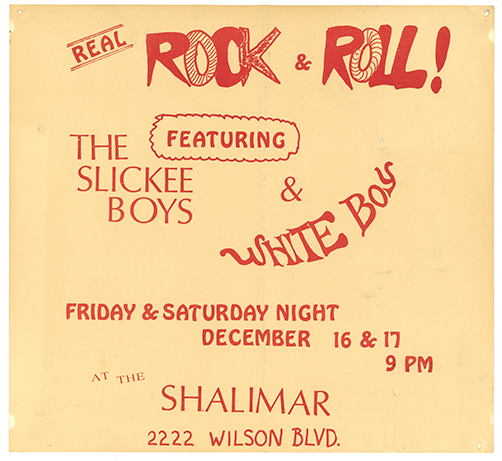

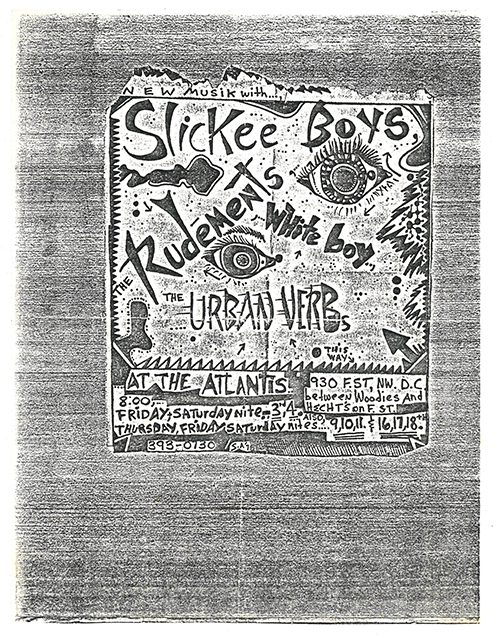

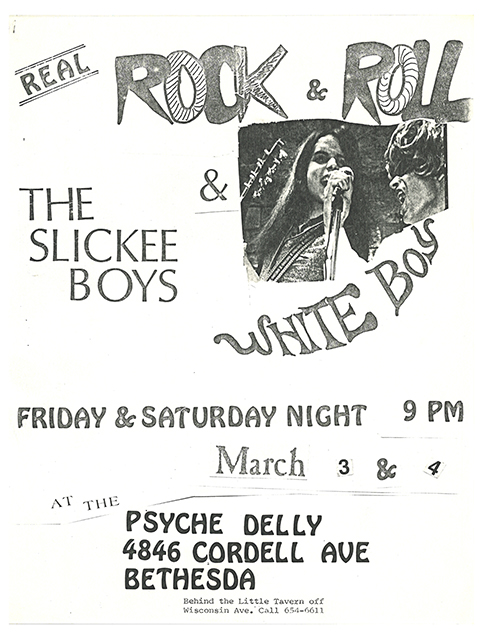

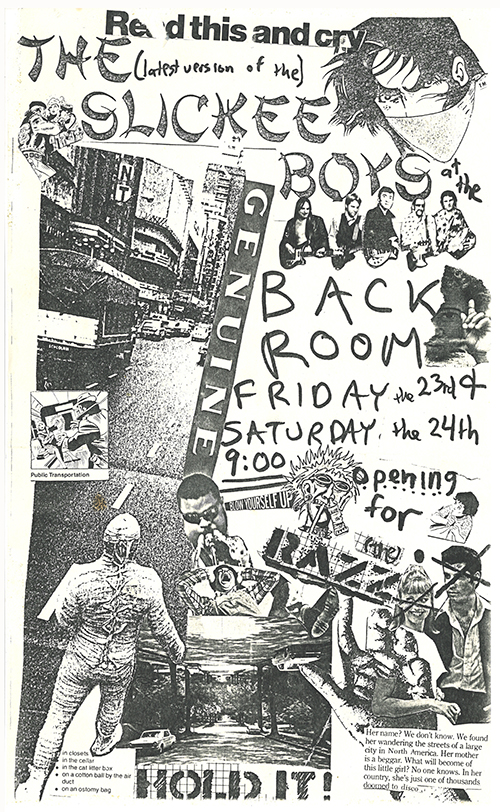

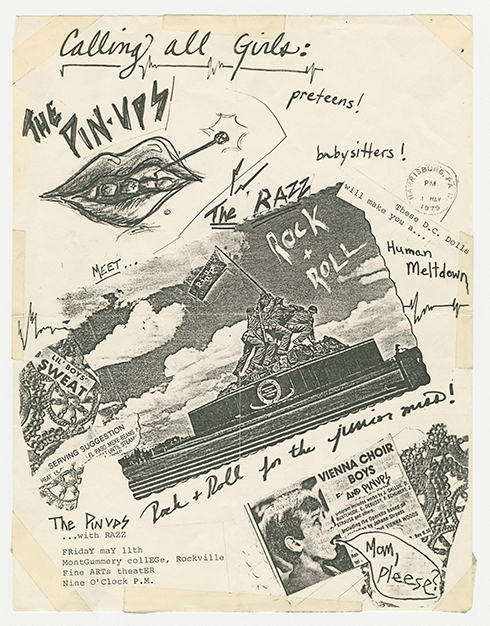

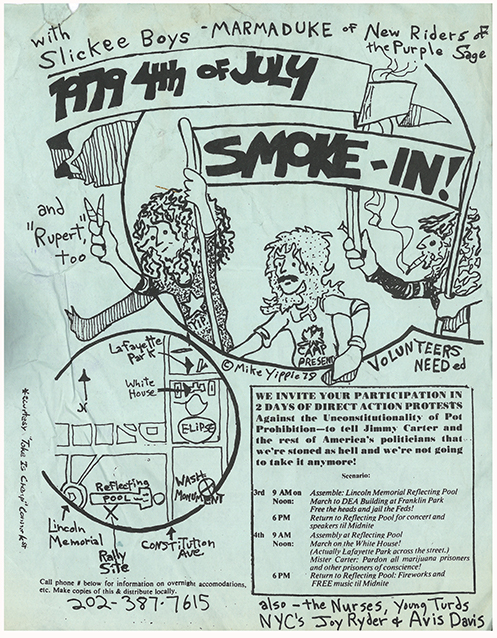

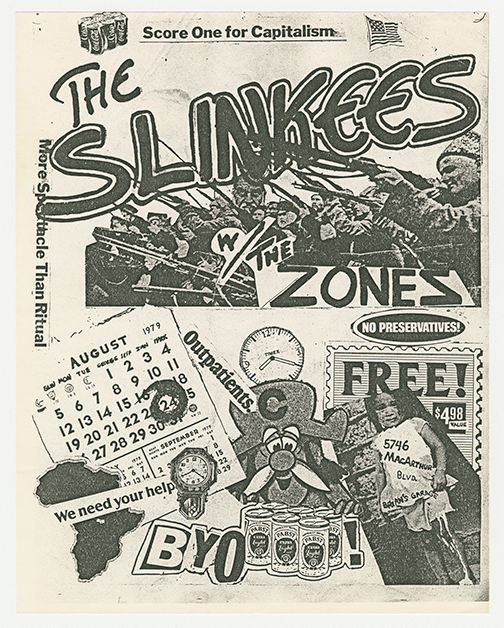

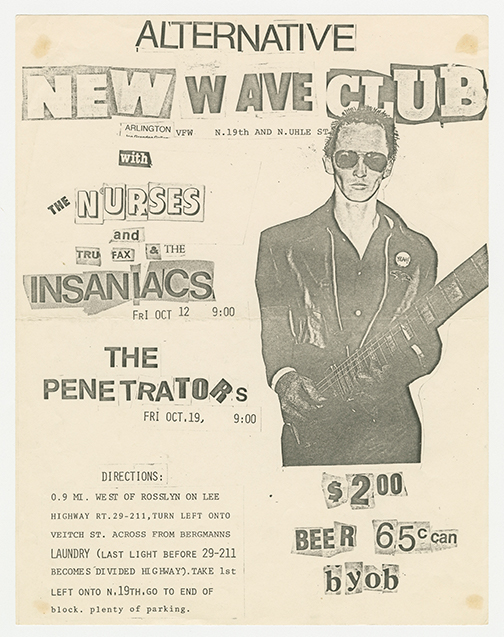

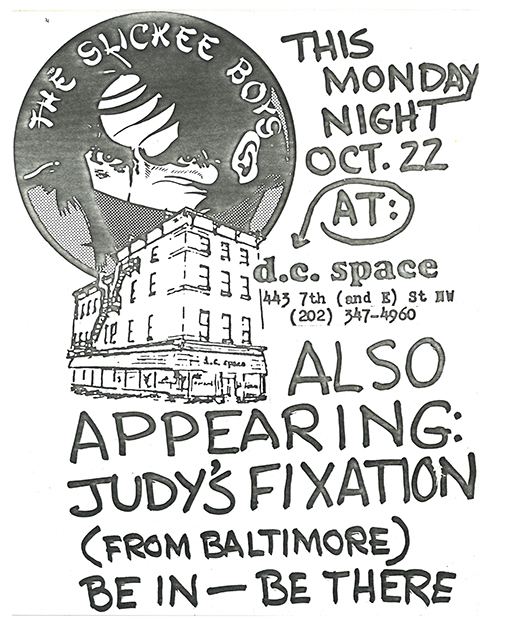

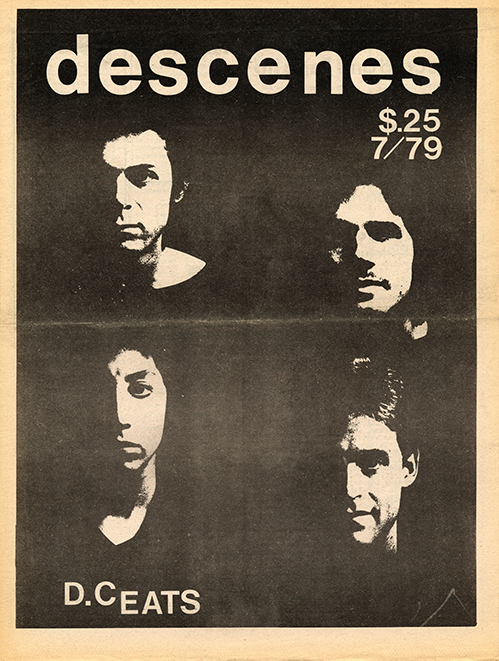

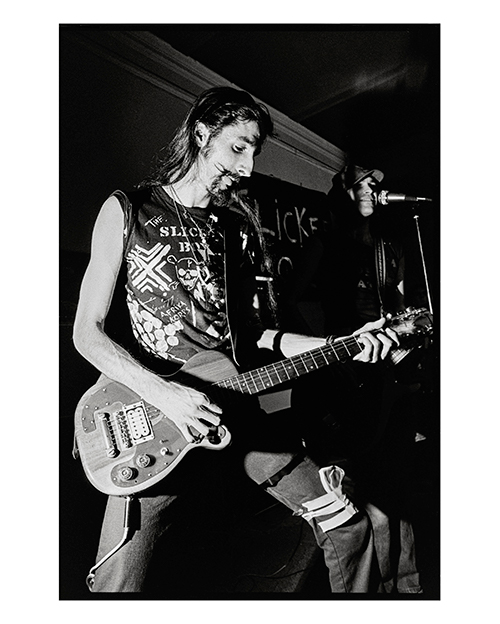

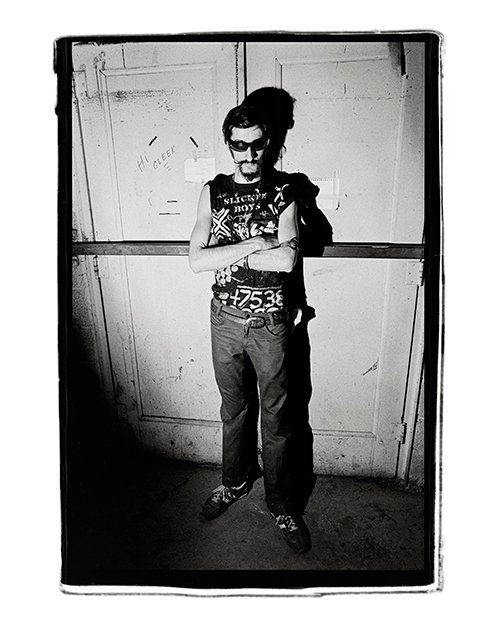

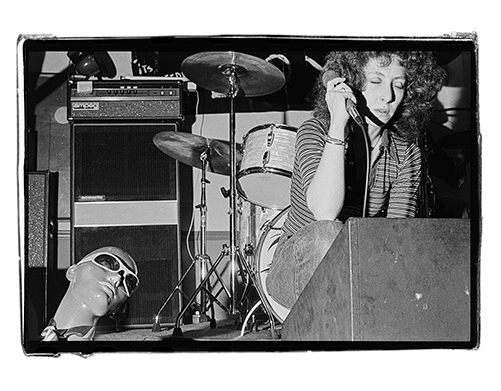

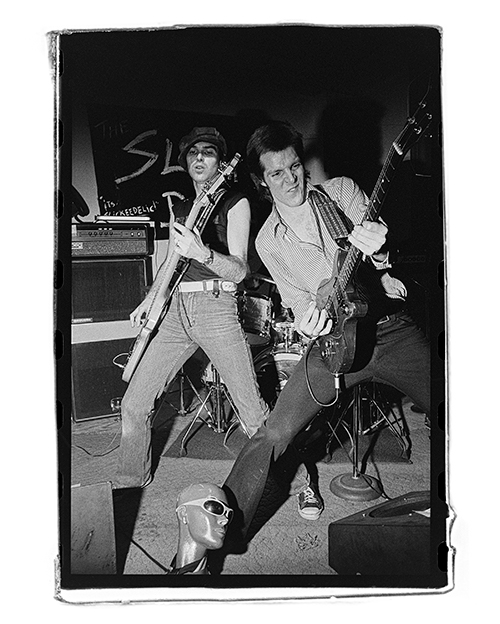

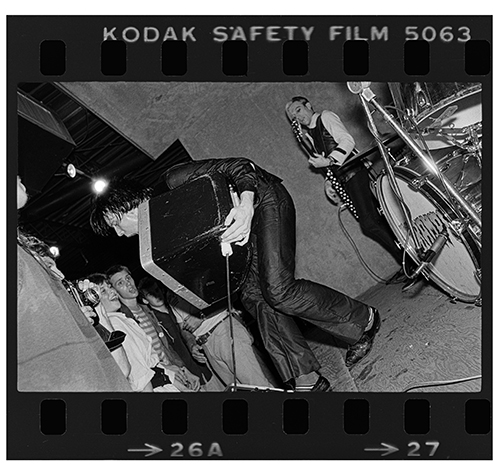

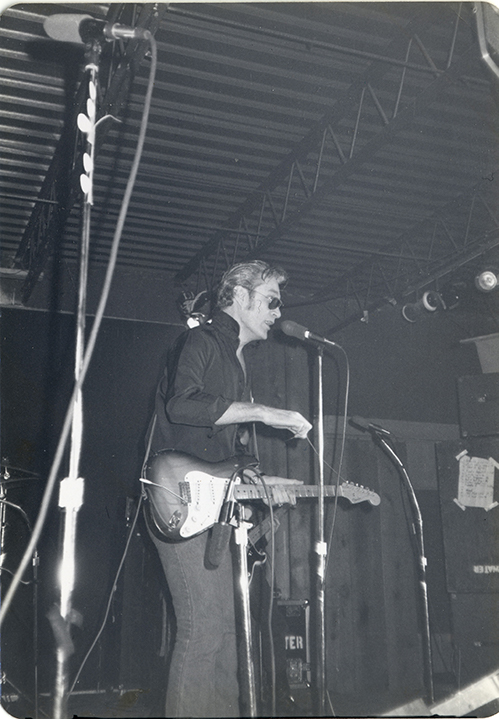

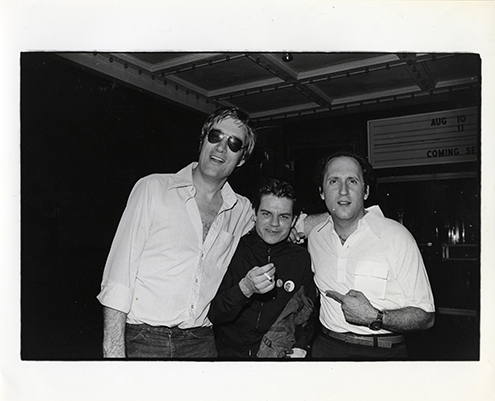

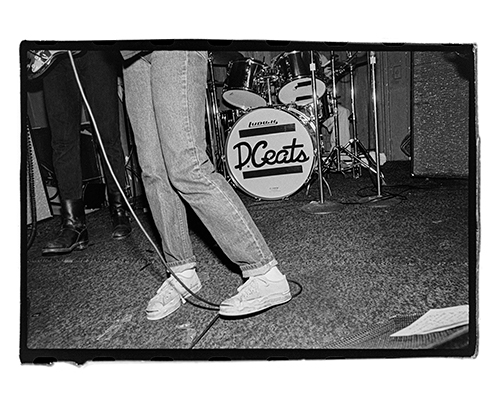

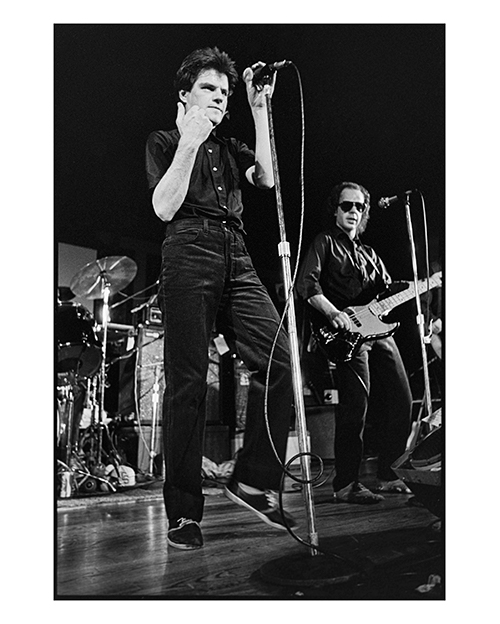

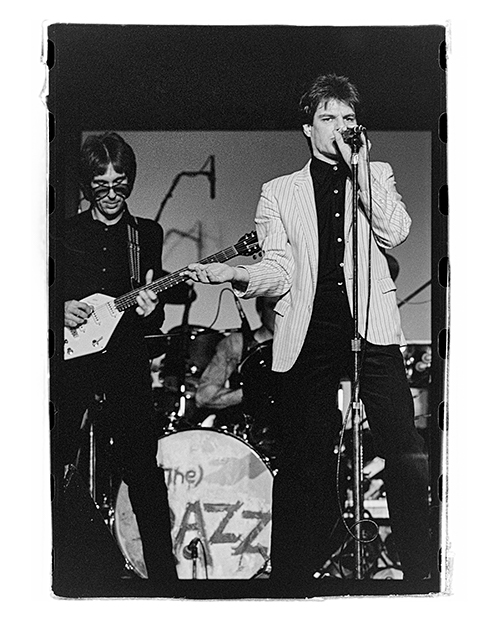

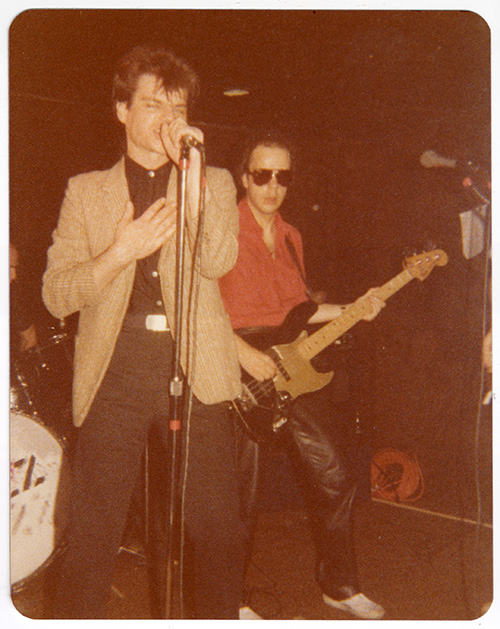

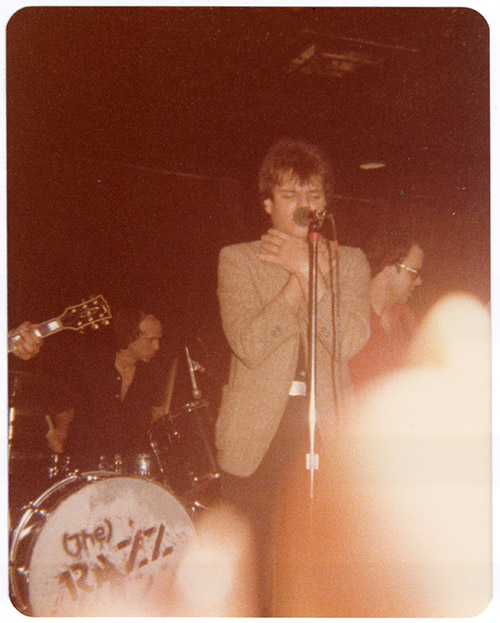

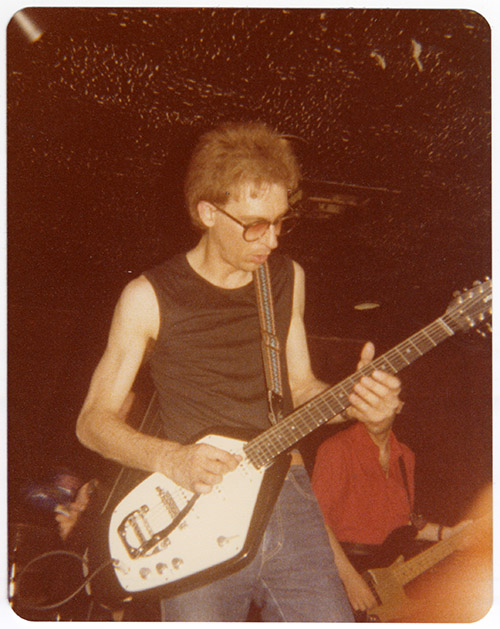

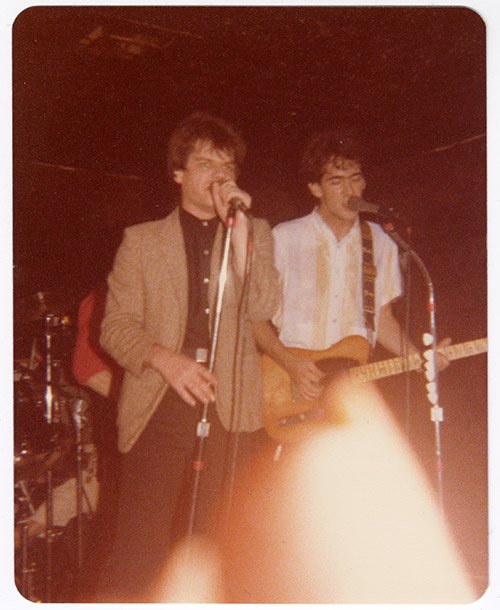

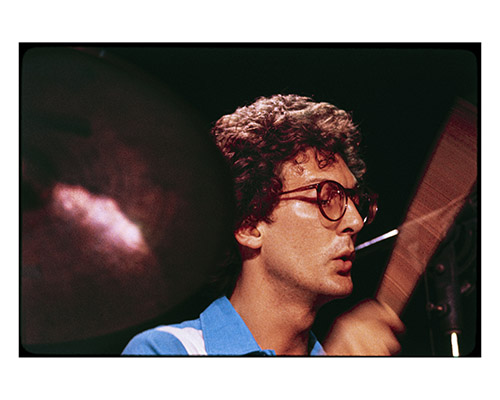

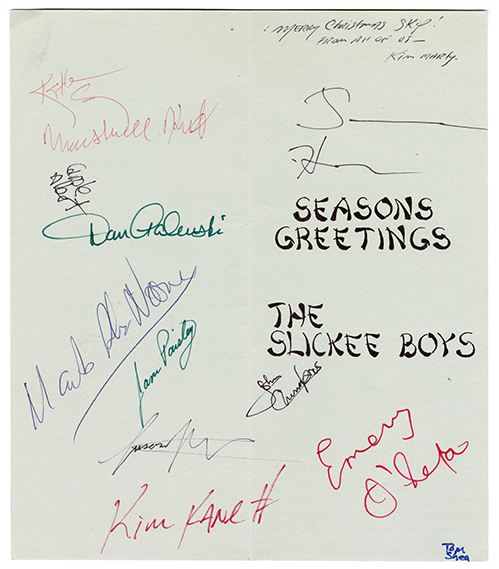

Beginning with the bands Overkill and the Slickee Boys in 1976, the Washington, DC area’s first wave of punk and new wave bands included groups like the Razz, Nurses, White Boy, Urban Verbs, the Shirkers, D. Ceats, and others. These bands forged a protean version of punk that, while generally lacking the ferocity of early punk standard bearers like the Sex Pistols from London or the Ramones from New York City, embraced eccentricity and humor to craft their own distinctive take on the genre. As Myron Bretholz of Unicorn Times—a DC arts newspaper among the earliest to cover local punk—wrote of an Overkill performance in the Summer of 1976, “in a city where a Dan Fogelberg show would probably sell out a month in advance, punk rock, my friends, is radical.”2

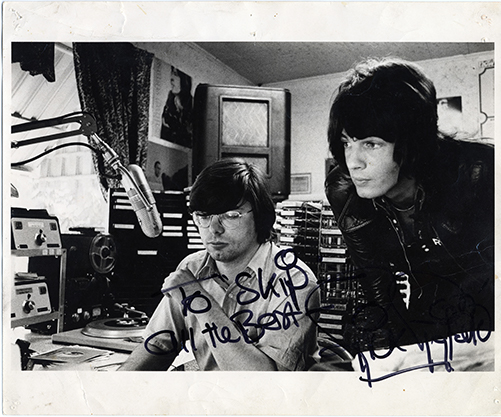

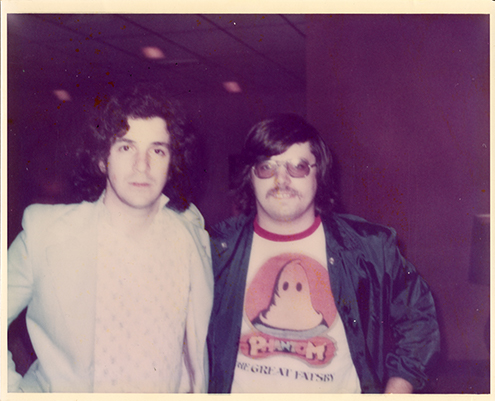

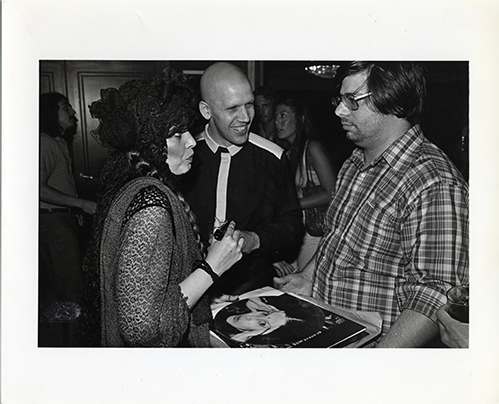

No record label was more central to the nascent punk scene in DC than Limp Records. Operated by Skip Groff, Limp provided the DC punk community with its first proper record label, which Groff ran out of his Rockville, Maryland record store, Yesterday & Today. Rather than a label centering around the efforts of a single band—as most other new DC punk labels were—Limp issued singles for several groups, often collaborating with the fledgling Dacoit and O’Rourke labels (the respective homes of the Slickee Boys and the Razz). Yesterday & Today, which opened in September 1977, was also a place where DC punks could purchase rare British punk singles, which Groff would handpick on buying trips to England, giving participants in the new subculture access to otherwise unavailable music.

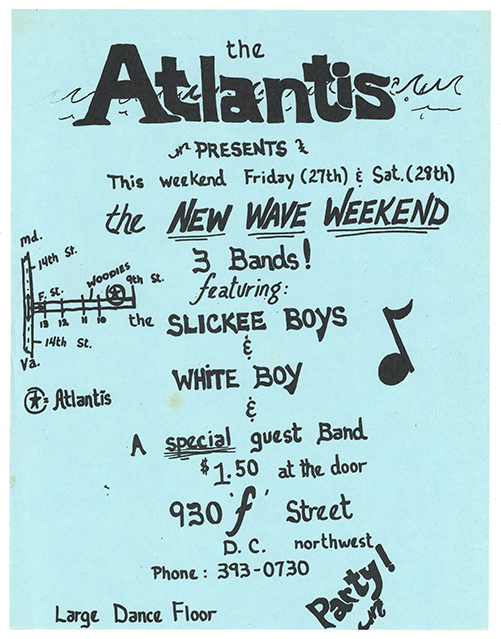

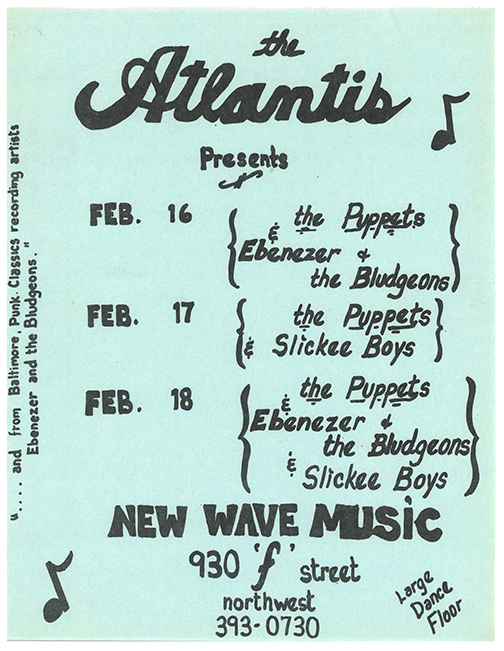

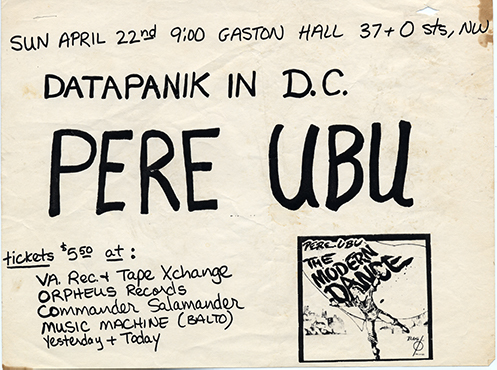

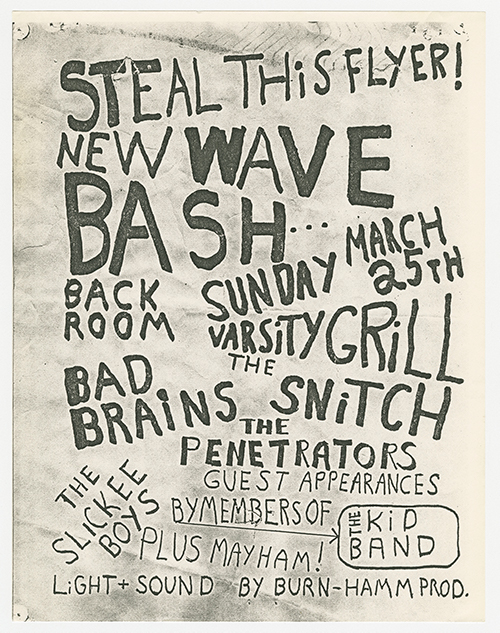

Another significant step in the scene’s evolution occurred in January 1978 when punk and new wave bands began performing regularly at the Atlantis, a club located at 930 F Street NW in DC. Before the Atlantis existed, DC punk and new wave bands scratched out gigs at rock bars around town like the Keg, Psyche Delly, My Friend’s House, or the Varsity Grill Back Room. With their bookings often relegated to sparsely attended off-nights, DC punk bands needed a venue that could serve as a reliable hub. The Atlantis was the first club in the DC area to forge its identity around “new wave,” punk’s less menacing sibling genre. Tension between club management and punk bands increased throughout the first half of 1978, however, primarily due to arguments over the Atlantis’ business practices. Many bands and patrons from the punk subculture engaged in a boycott of the Atlantis, with the conspicuous exception of Urban Verbs. Club management capitulated to terms of the boycott and some bands returned to the Atlantis stage, but the venue shuttered in early 1979.

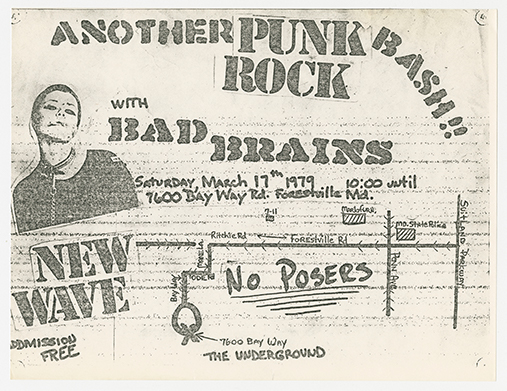

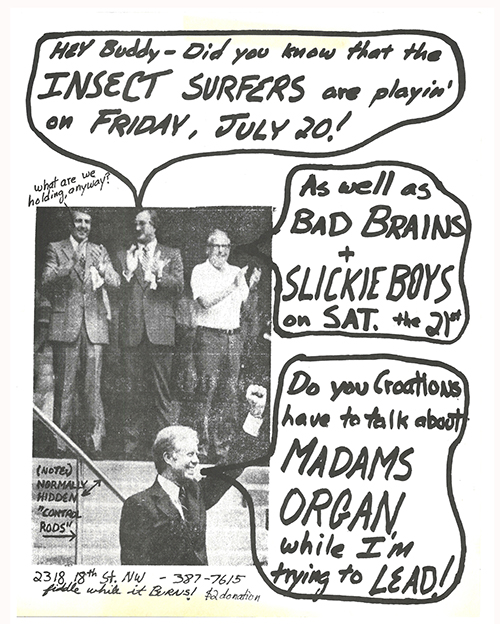

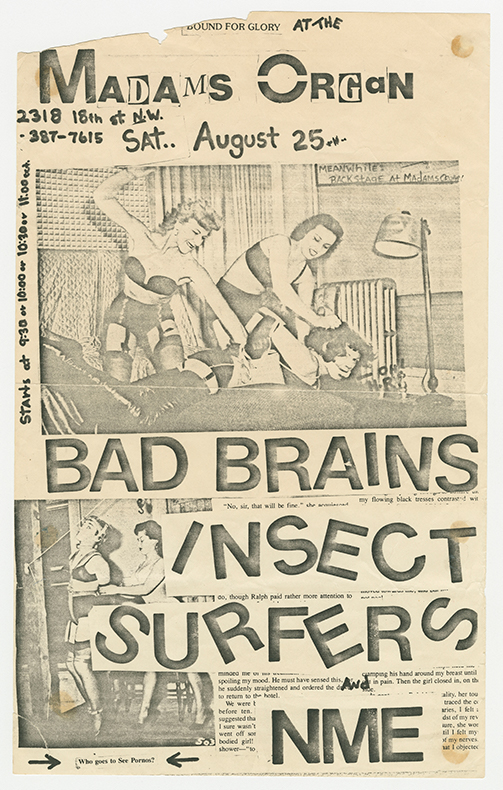

That year was key in the development of the DC punk scene. The Slickee Boys and the Razz each released their best music in 1979, though the latter would disband by year’s end. Two new bands—Bad Brains and the Teen Idles—debuted and, wielding a faster and more aggressive take on punk, took the first steps toward transforming DC’s scene into one of international influence. Bad Brains made themselves known locally throughout 1979 as a band whose ferocious tempos, positive lyrics, and kinetic performances combined to move them to the scene’s vanguard. Musician and author Henry Rollins, then known as Henry Garfield, described seeing Bad Brains open for the pioneering British punk band the Damned at the Bayou in DC on June 24, 1979: “When they all walked offstage, we all looked at each other and said ‘That’s the best band in the world.’”3

DC punk would not have taken shape the way it did without Groff’s efforts, particularly considering his connections with Bad Brains and the Slickee Boys and his musical and entrepreneurial influence on Ian MacKaye and Jeff Nelson of the Teen Idles, who would heed Groff’s advice to co-found Dischord Records in 1980, the scene’s flagship record label for decades to come.

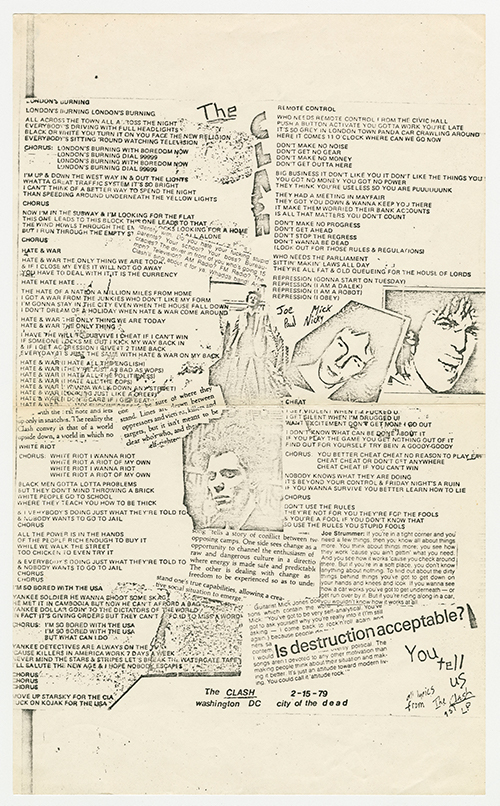

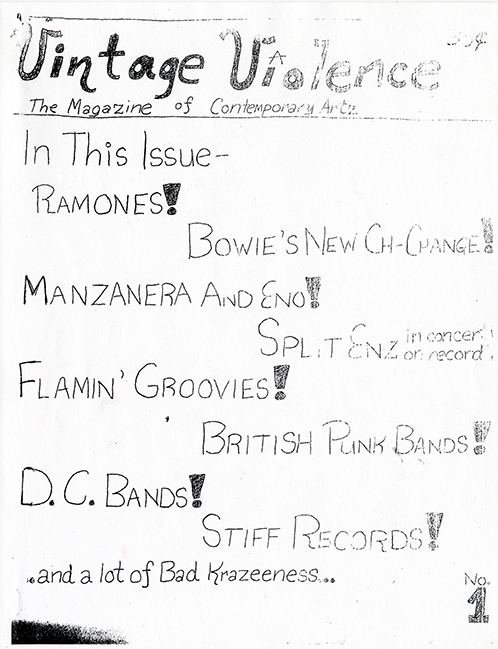

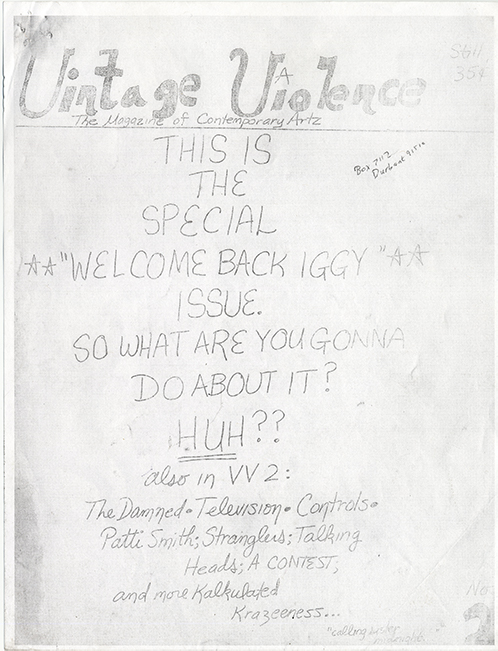

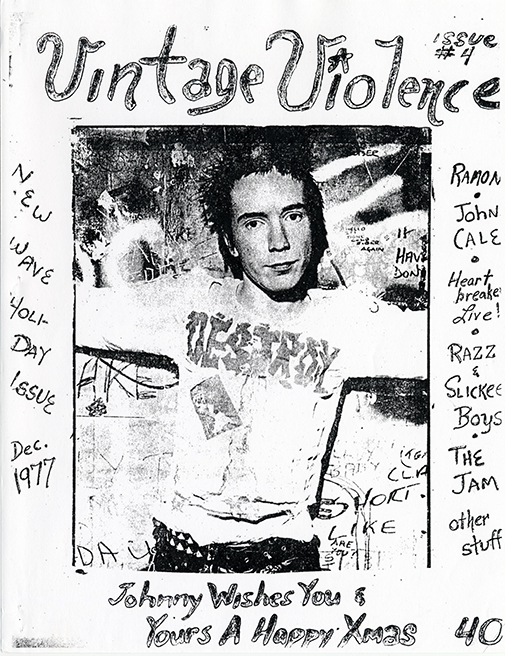

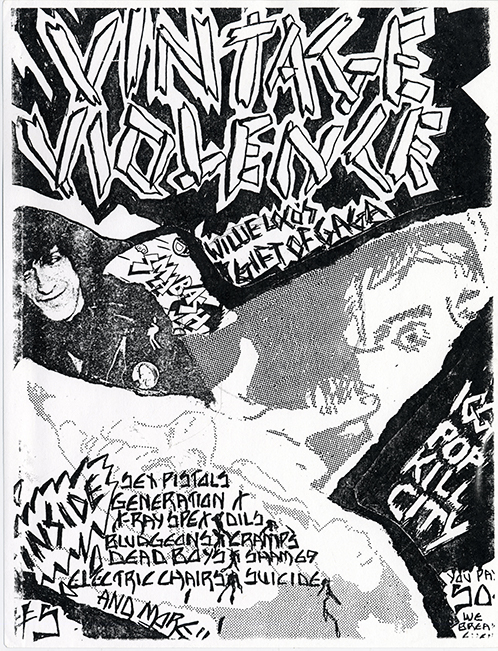

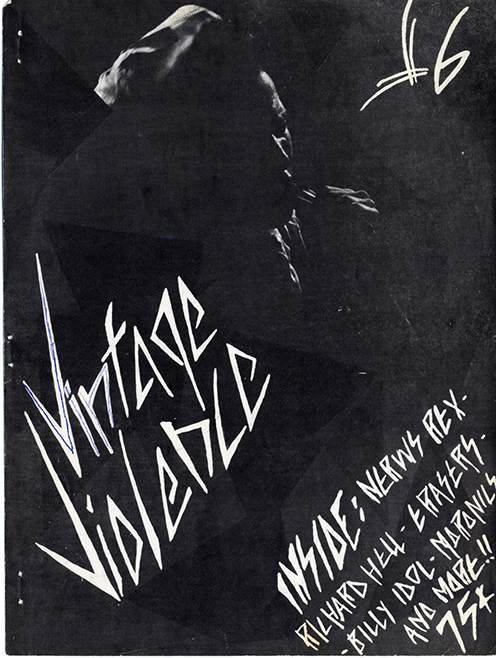

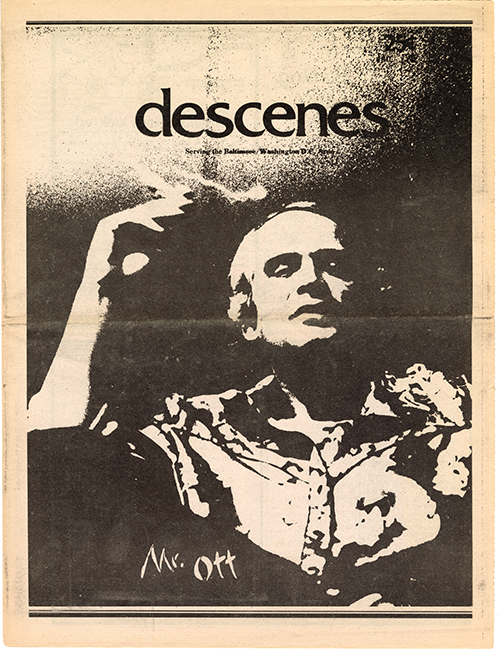

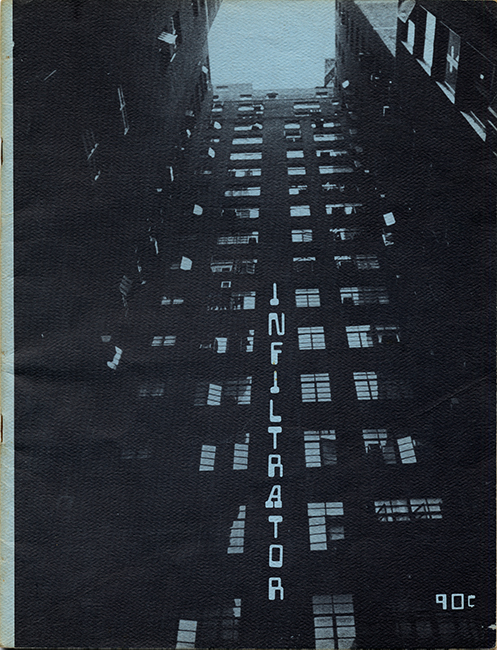

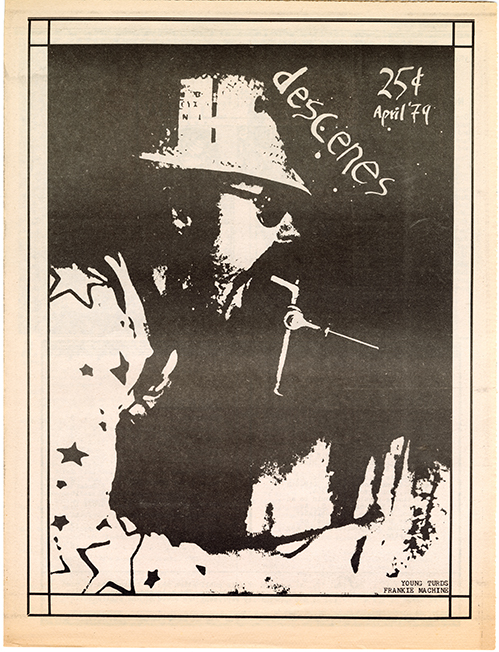

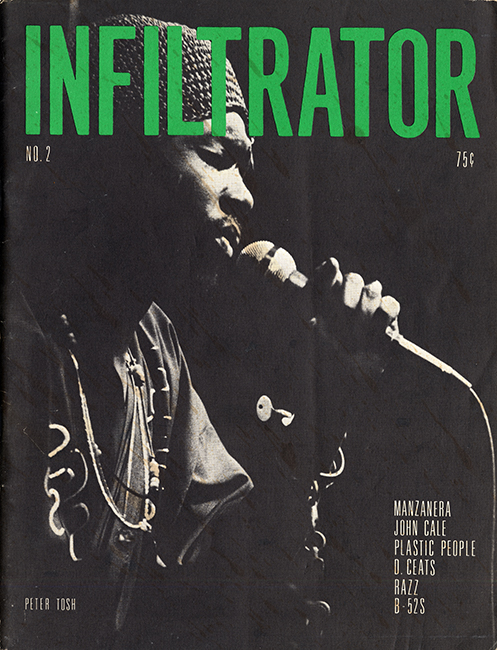

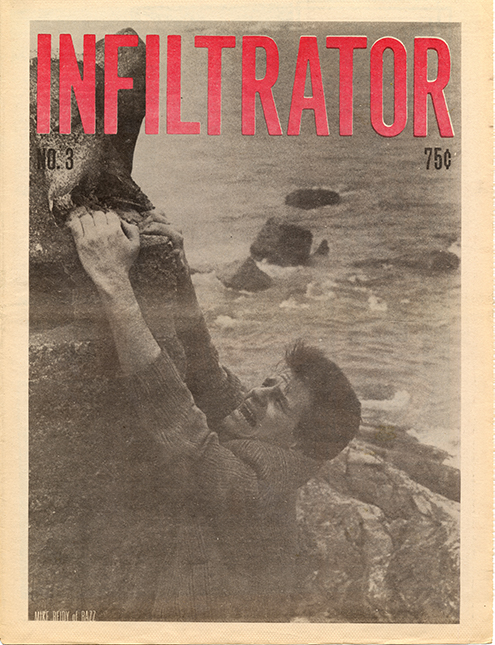

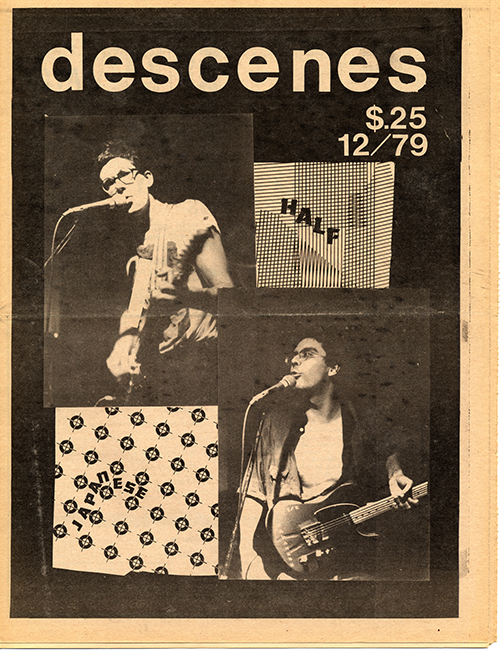

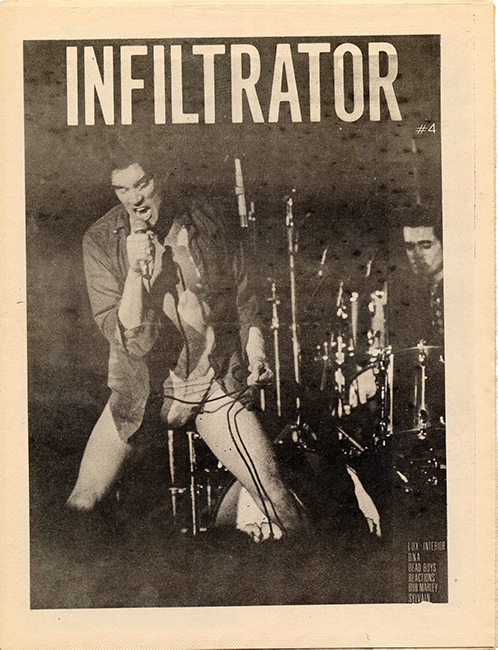

Along with airplay on college radio stations like Georgetown’s WGTB and the University of Maryland’s WMUC, fanzines and concert fliers were critical methods of communication within punk scenes, which generally received scant coverage from mainstream media outlets. The earliest DC-area zines to develop under the influence of punk were It’s Only a Movie and Vintage Violence, which debuted in Fall 1976 and March 1977, respectively. Vintage Violence, in particular, was the first local zine to offer extensive coverage of the Slickee Boys and other founding DC punk groups—none of whom ever released recordings—like the Look and the Controls. Vintage Violence developed into a sharply stylized punk zine before publishing its final issue in 1978. Two more DC punk zines—Descenes and The Infiltrator—debuted in 1979, broadening the scope of the scene’s writing and design acumen while offering substantial interviews with many of DC’s central punk and new wave bands.

Further Listening

The Chumps - "Air Conditioner" - 7-inch single - Round Raoul Records, 1979.

D. Ceats - Monumental - 7-inch EP - Limp Records, 1979.

Nurses - "Hearts" - 7-inch single - Round Raoul Records, 1979.

The Razz - Air Time - 7-inch EP - Limp Records/O’Rourke Records, 1979.

The Razz - "You Can Run" - 7-inch single - Limp Records/O’Rourke Records, 1979.

The Shirkers - "Drunk and Disorderly" - 7-inch single - Limp Records, 1978.

The Slickee Boys - Hot and Cold - 7-inch EP - Dacoit Records, 1976.

The Slickee Boys - Mersey Mersey Me - 7-inch EP - Limp Records, 1978.

The Slickee Boys - Third- 7-inch EP - Limp Records, 1979.

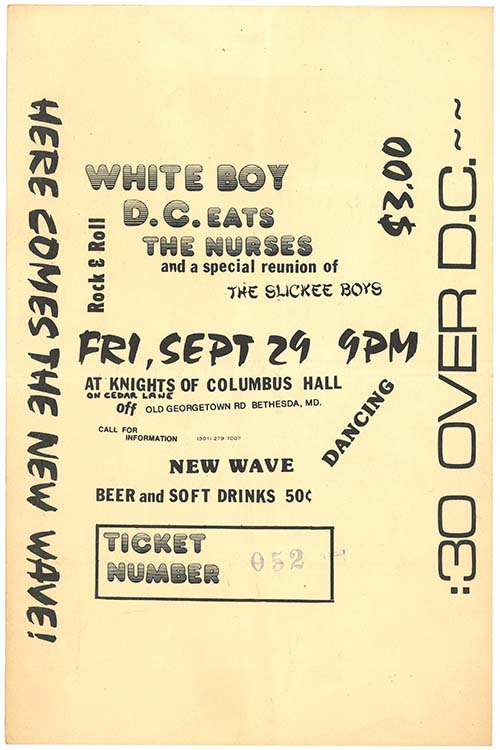

Various Artists - :30 Over DC: Here Comes the New Wave (featuring the Slickee Boys, Nurses, Half Japanese, Penetrators, and others) - compilation LP - Limp Records, 1978.

White Boy - "Sagittarius Bumpersticker" - 7-inch single - Doodley Squat Records, 1977.

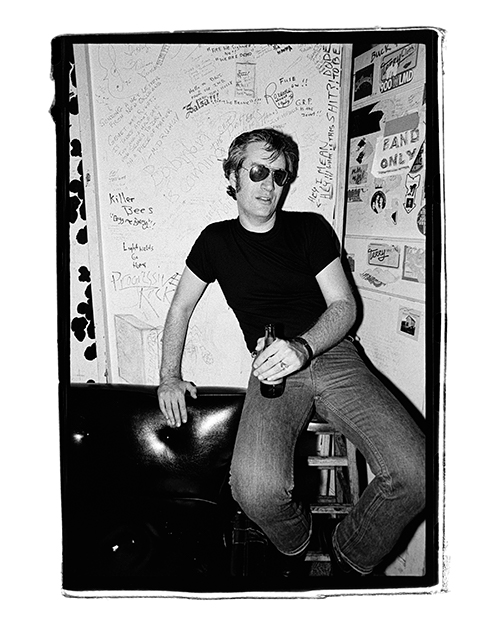

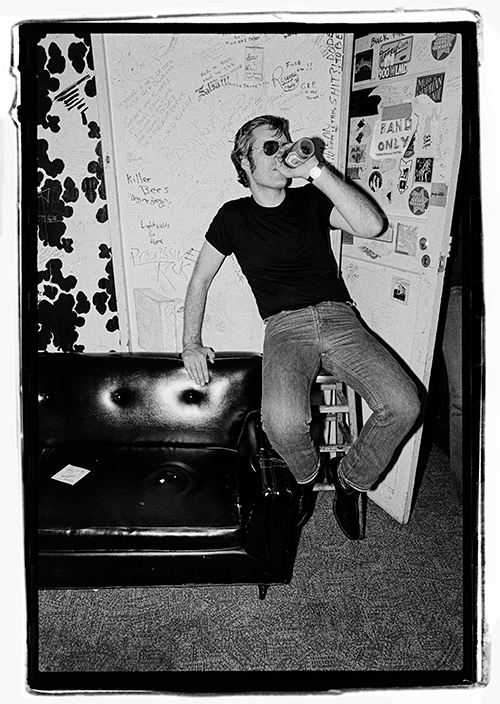

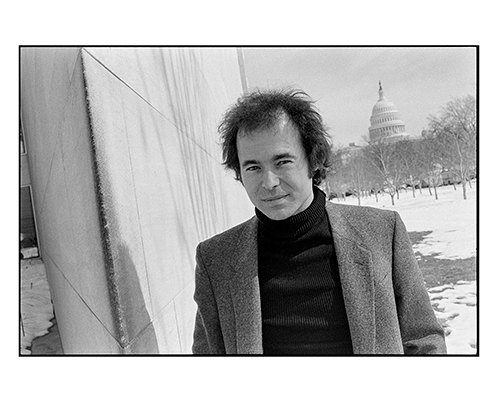

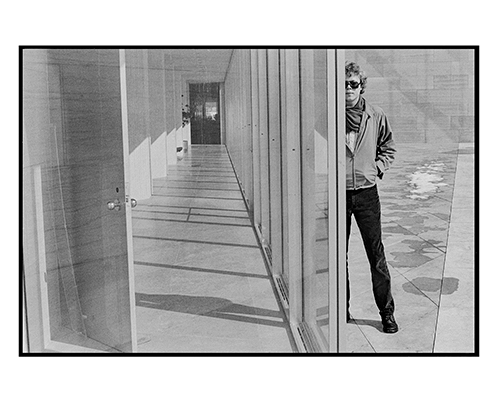

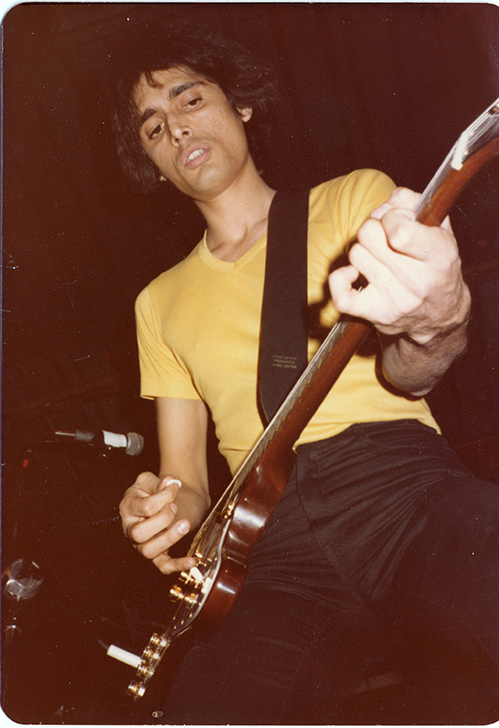

Materials are drawn from the Paul Bushmiller collection on punk, the Sharon Cheslow punk flyers collection, the Skip Groff papers, the Don Hamerman collection of performing arts photographs, and the Robbie White collection on the Slickee Boys.

Tap or hover over an image to learn more.

FLIERS

ZINES

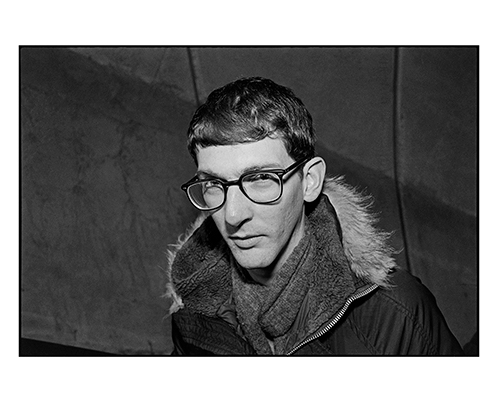

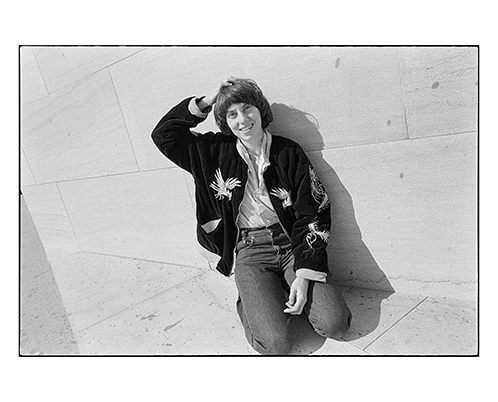

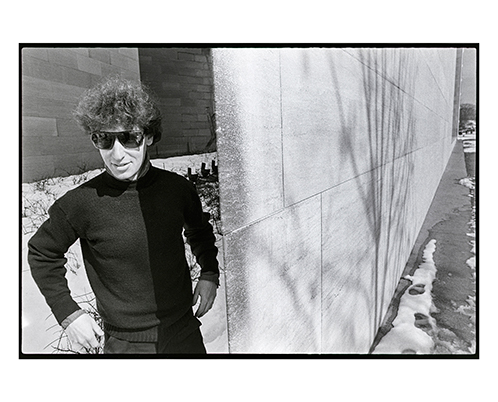

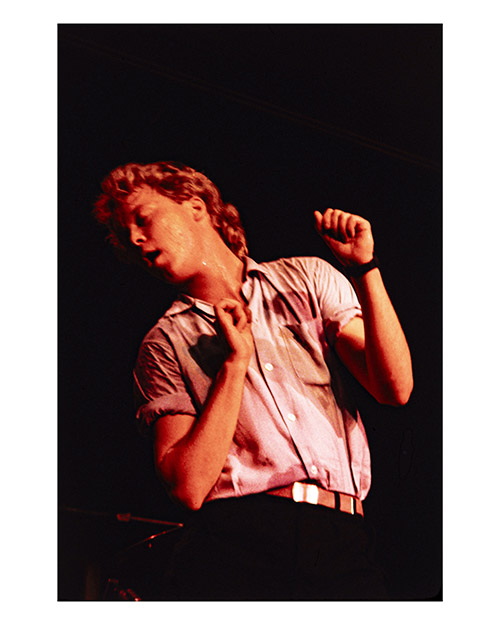

PHOTOS

EPHEMERA

RECORDINGS

Oral history interview with Michael Heath of Vintage Violence (1977-1979), recorded 2019

Tiny Desk Unit, performing at d.c. space, October 8, 1979

Insect Surfers interview and radio aircheck tape, November 1979