In 1983, conflict underpinned American life. From Reagan’s infamous "Evil Empire" speech, to the proposed laser-based nuclear defense program dubbed “Star Wars” to the invasion of Grenada and the United States' involvement in the Lebanese Civil War, America was entering into a tumultuous stretch of the decade.1, 2 The D.C. punk community, too, reflected the growing tension and frustration in American society, with the creative and ethical direction of the scene unclear at the same time that its popularity was exploding.

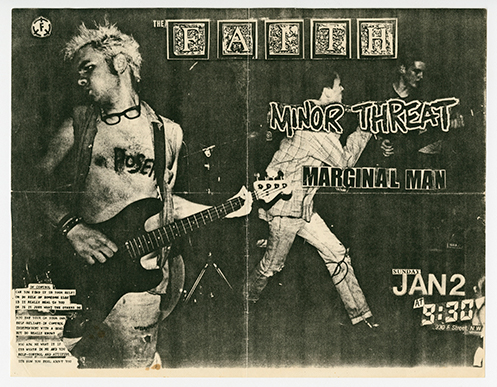

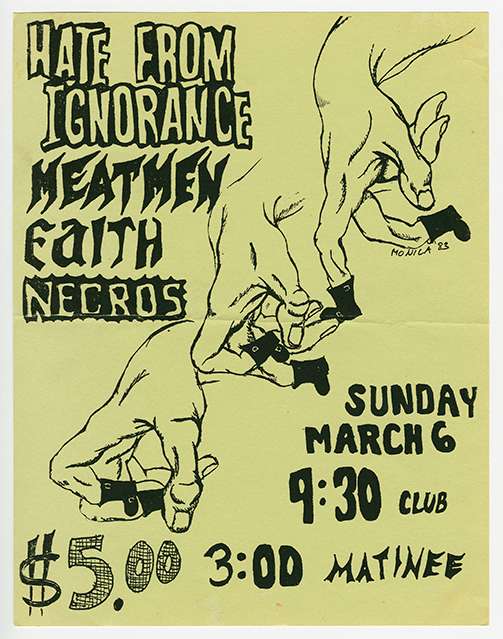

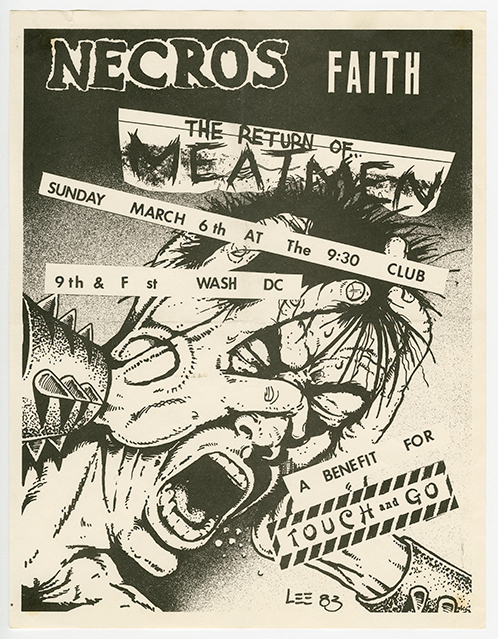

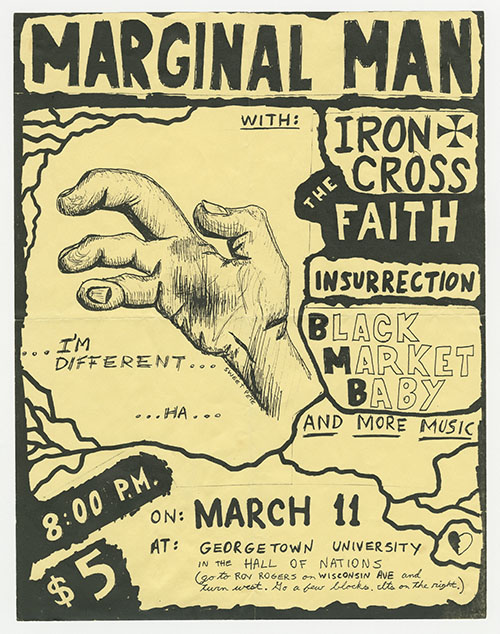

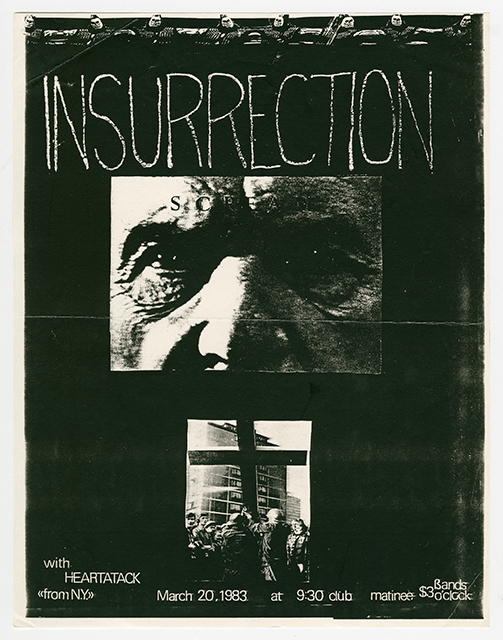

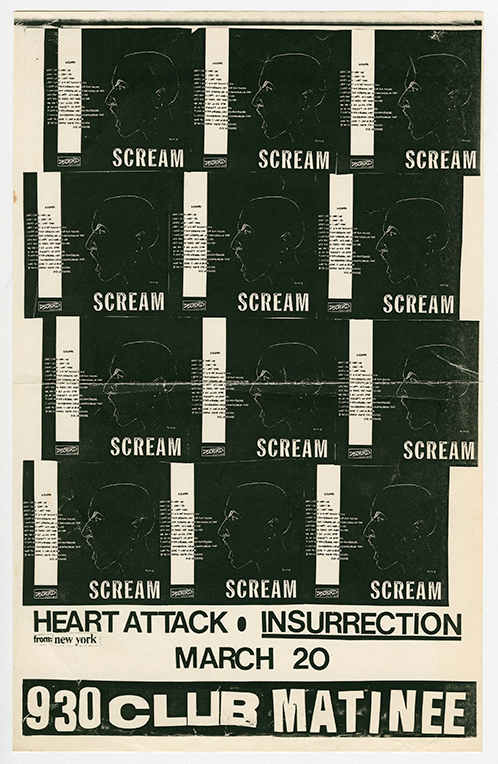

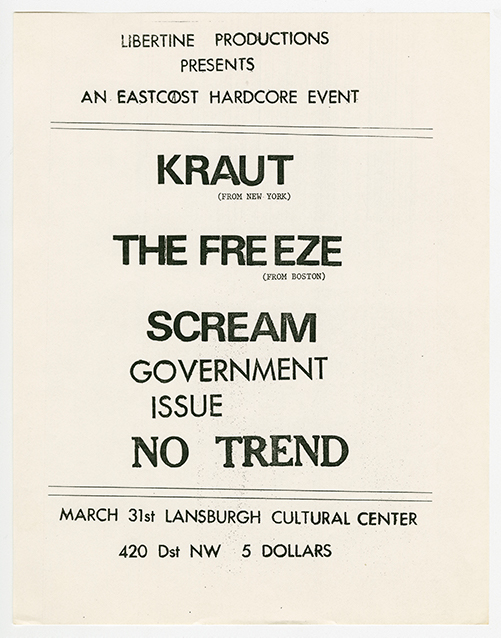

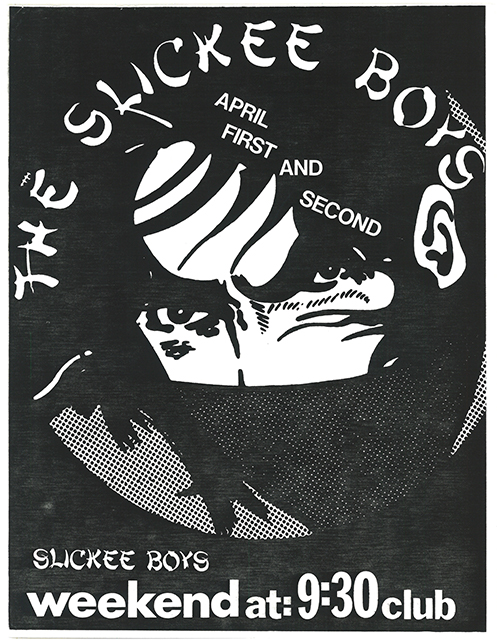

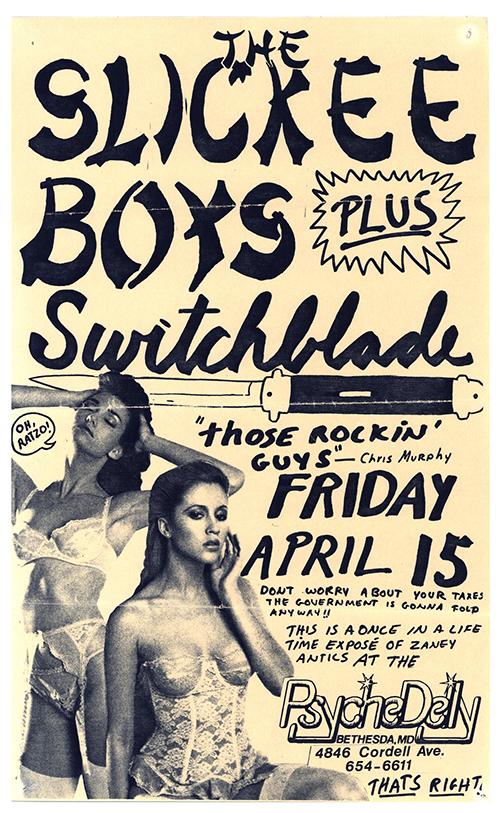

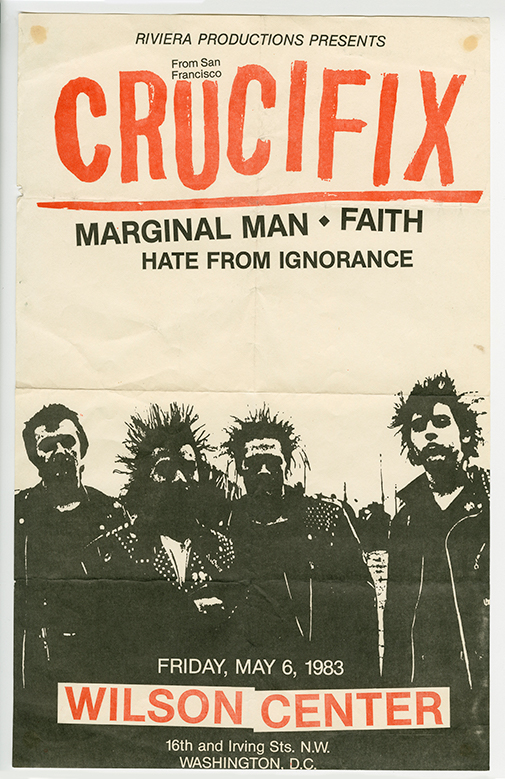

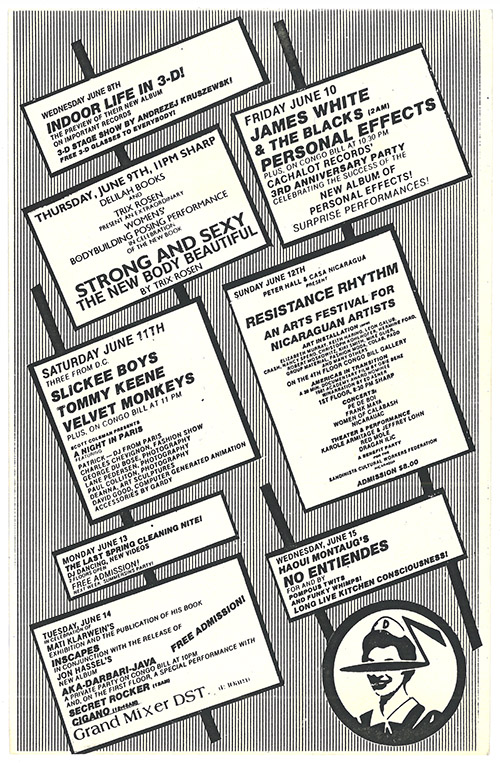

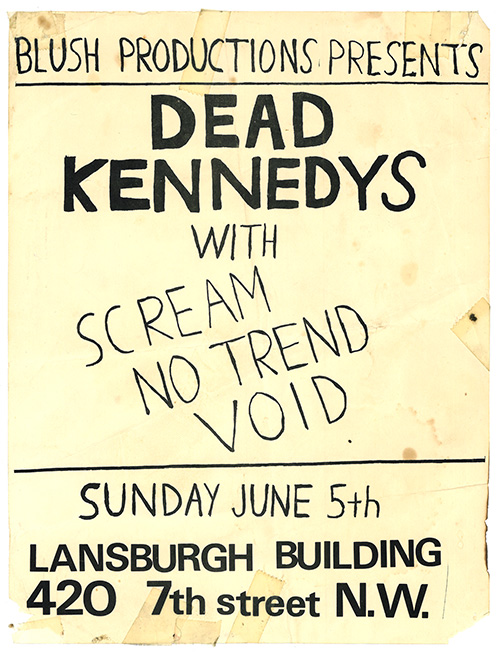

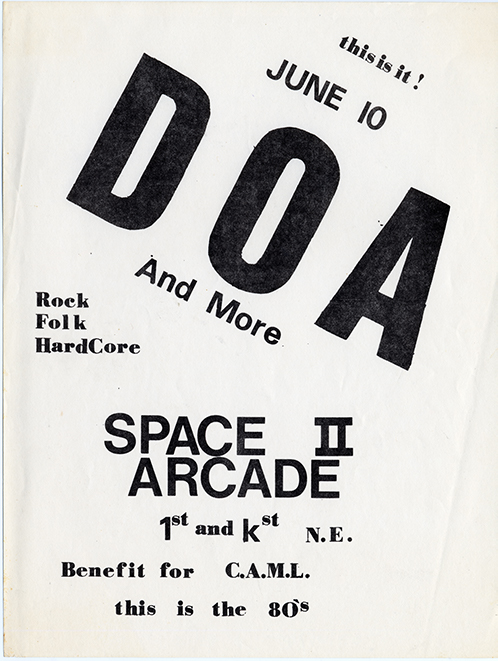

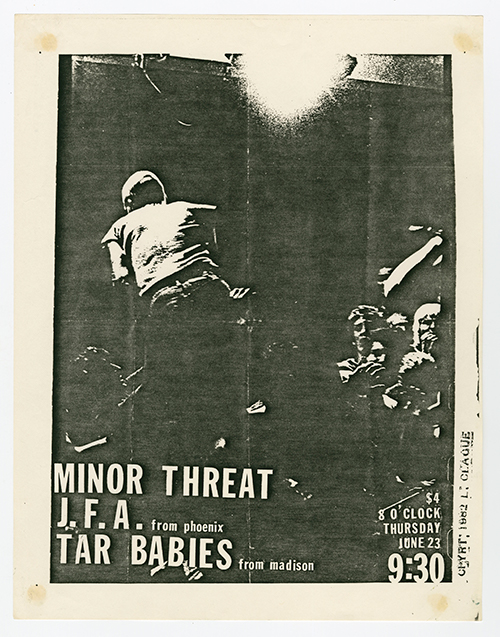

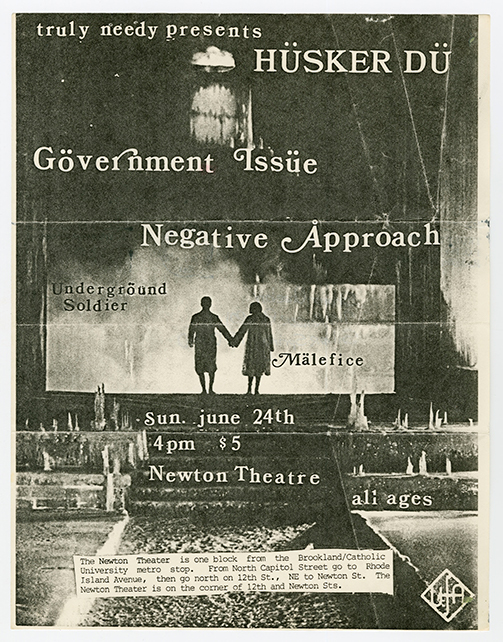

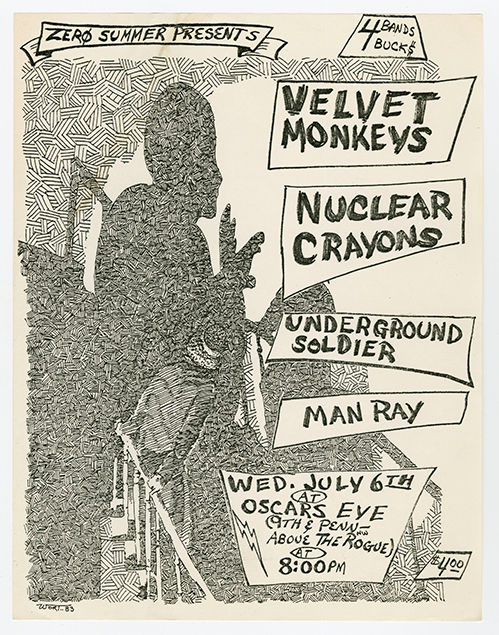

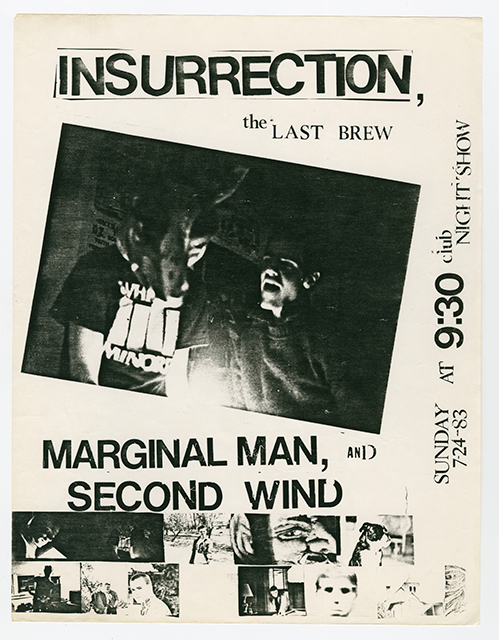

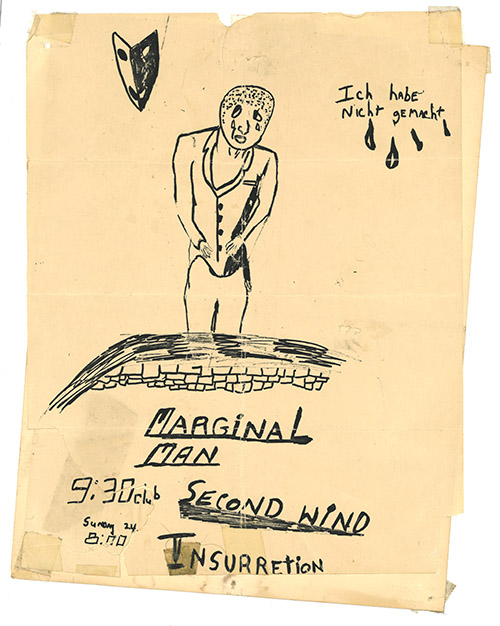

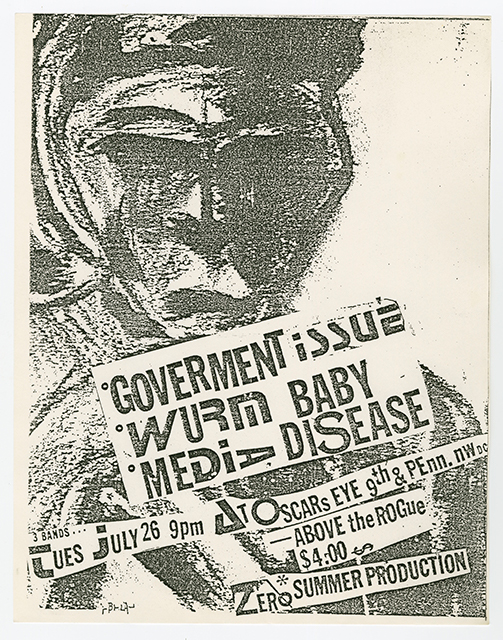

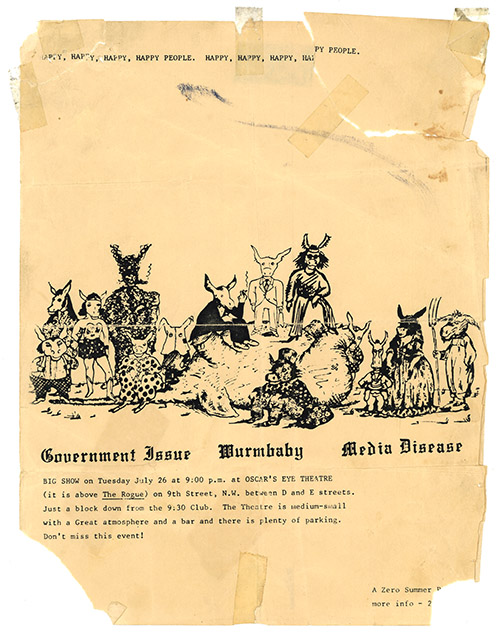

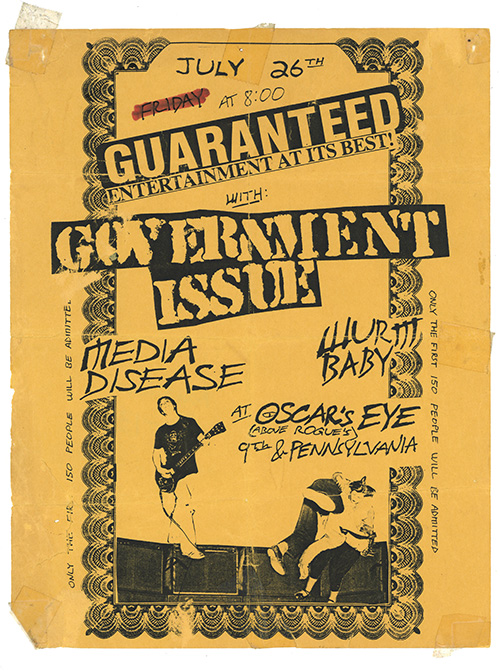

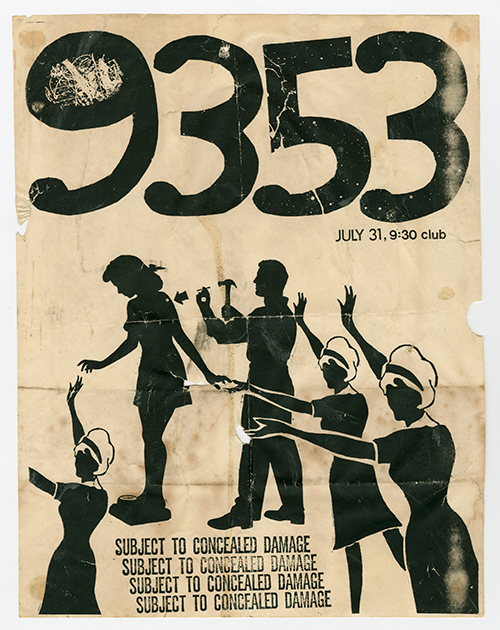

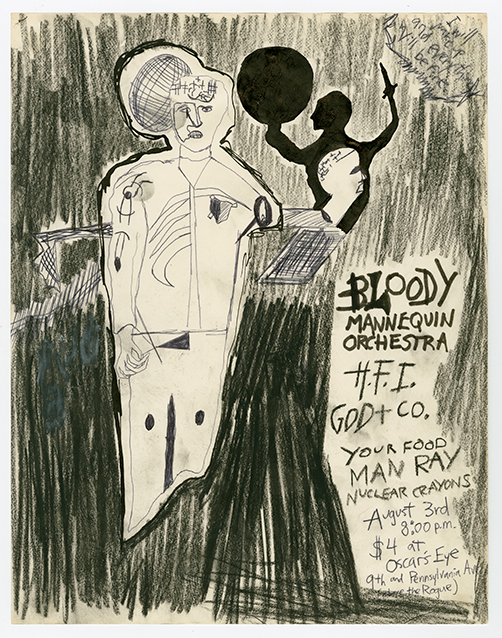

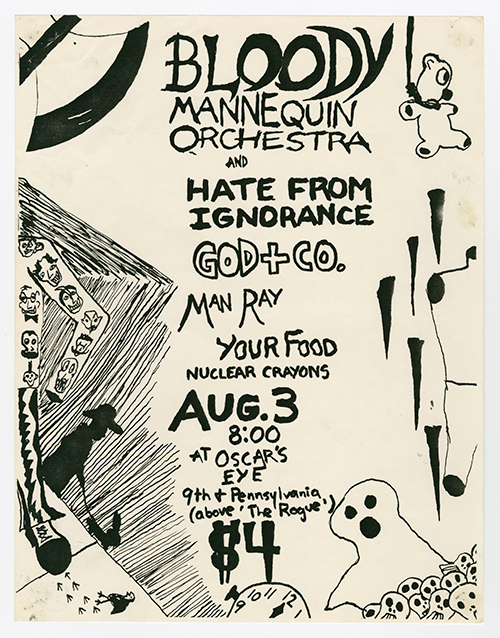

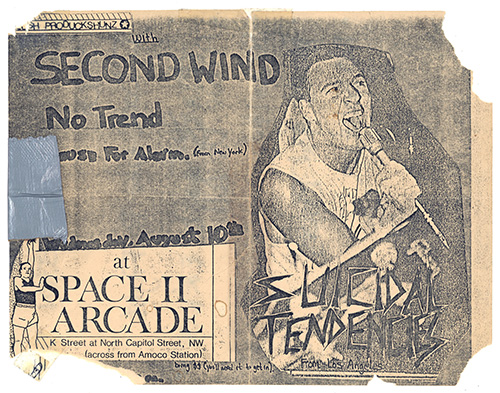

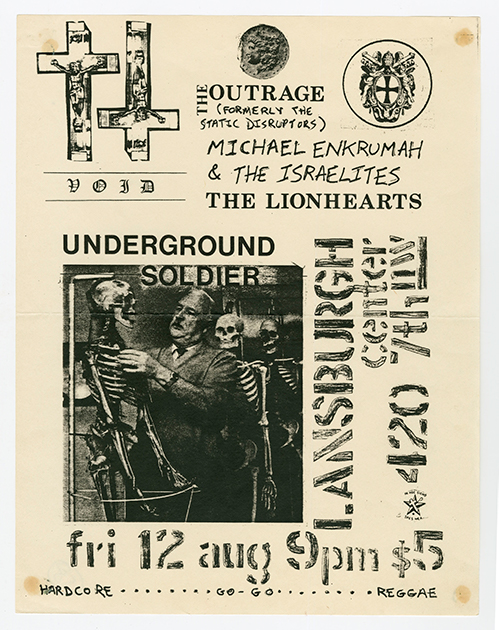

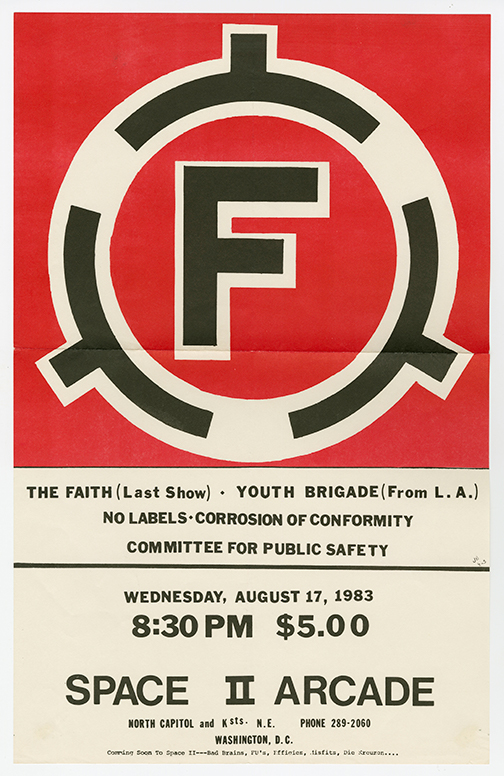

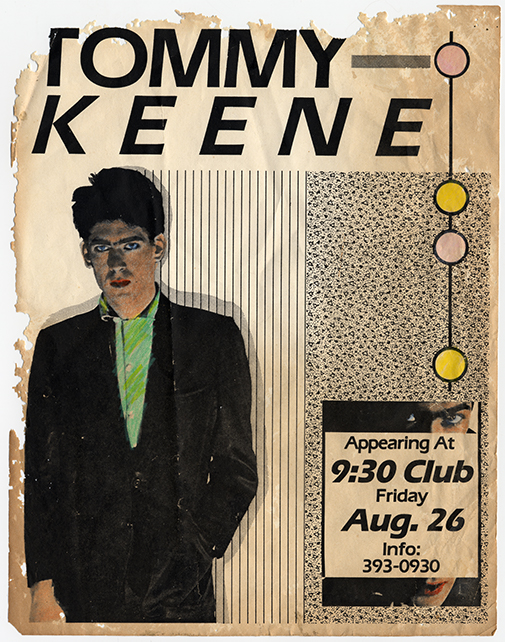

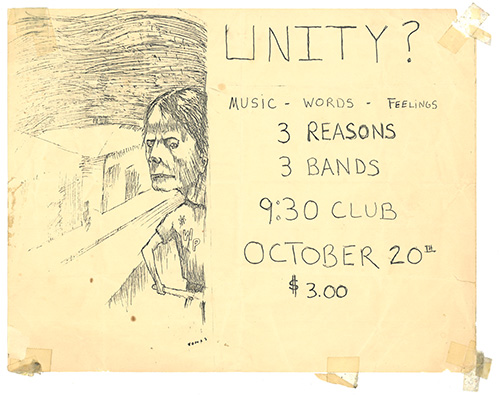

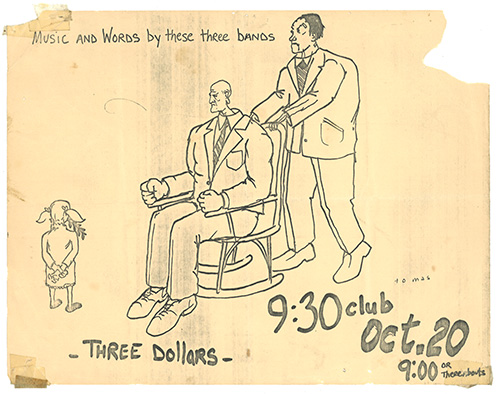

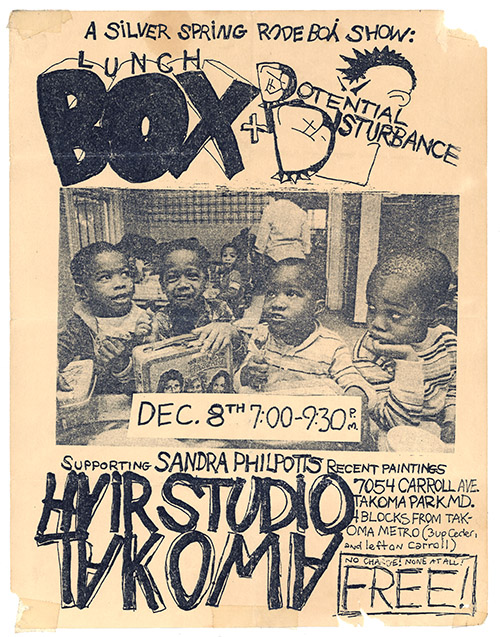

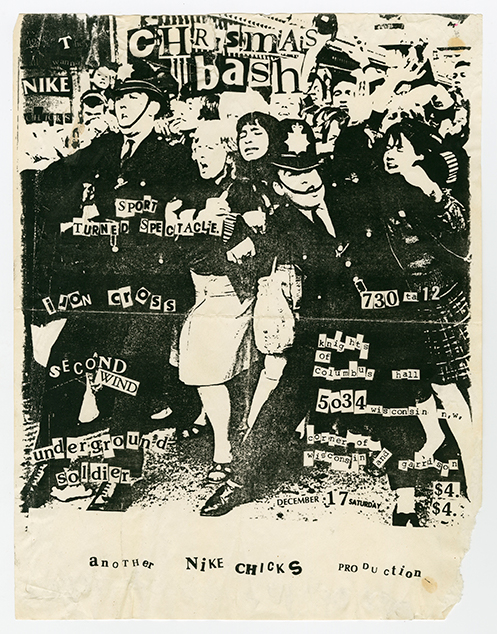

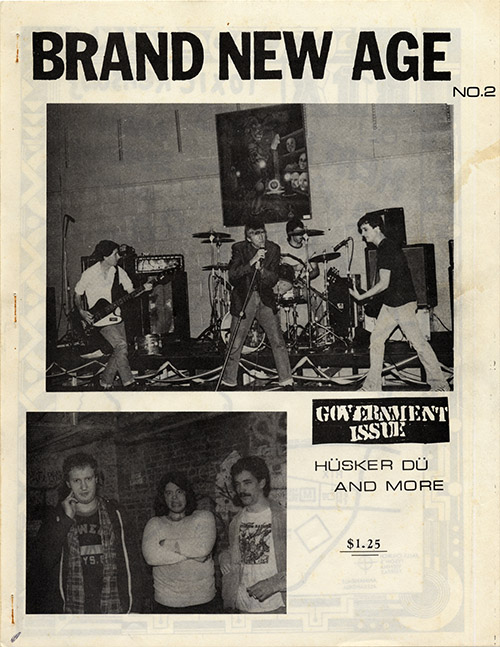

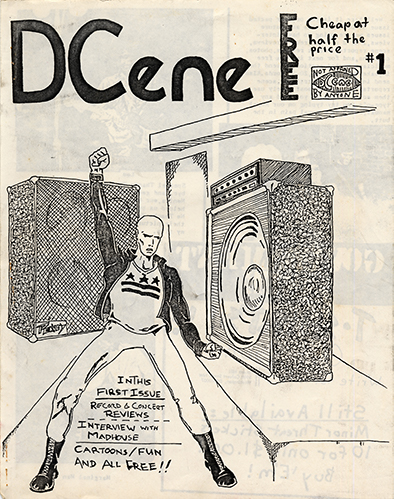

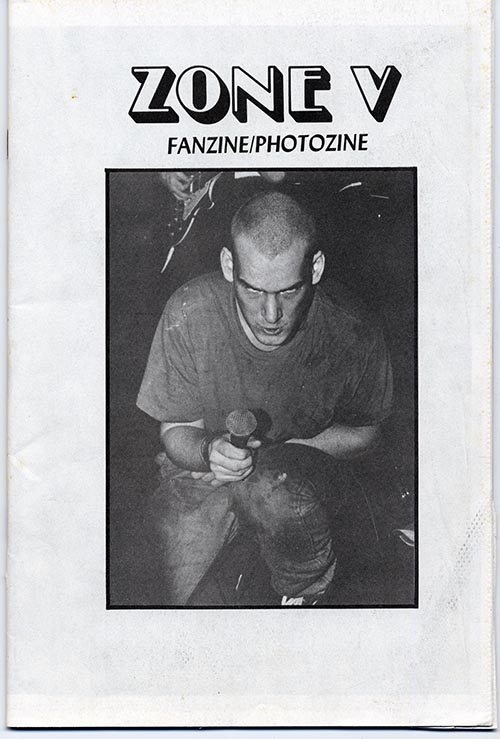

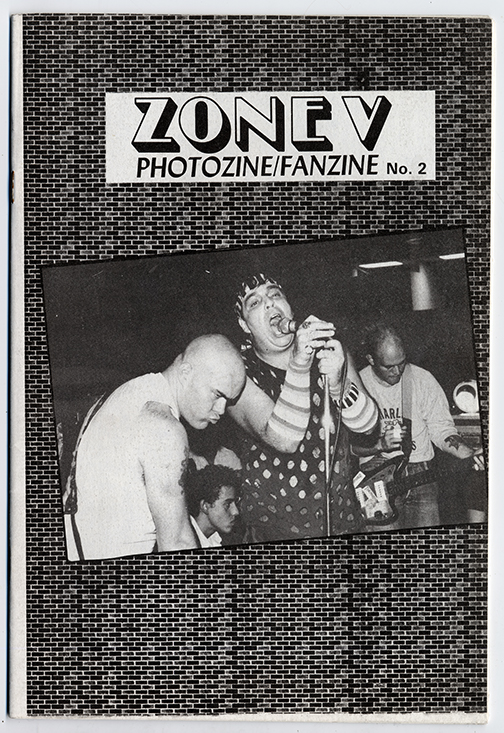

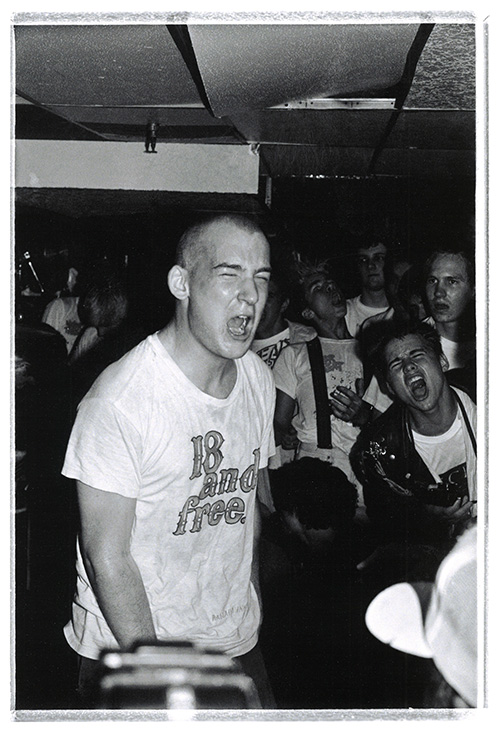

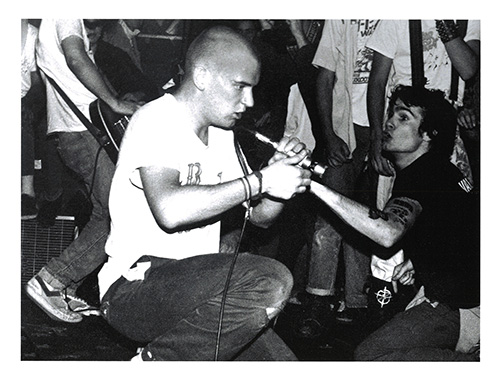

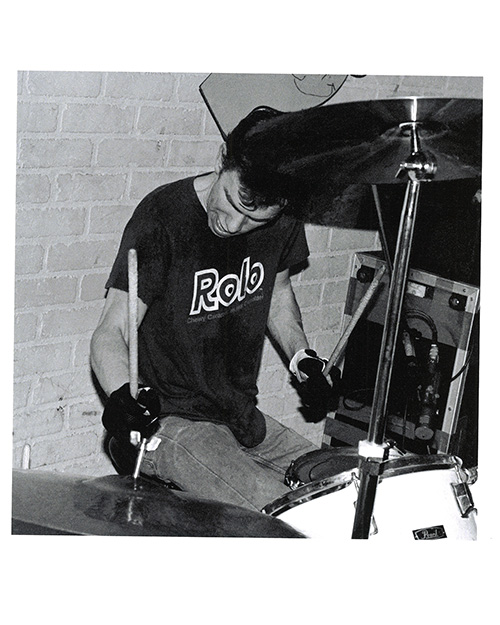

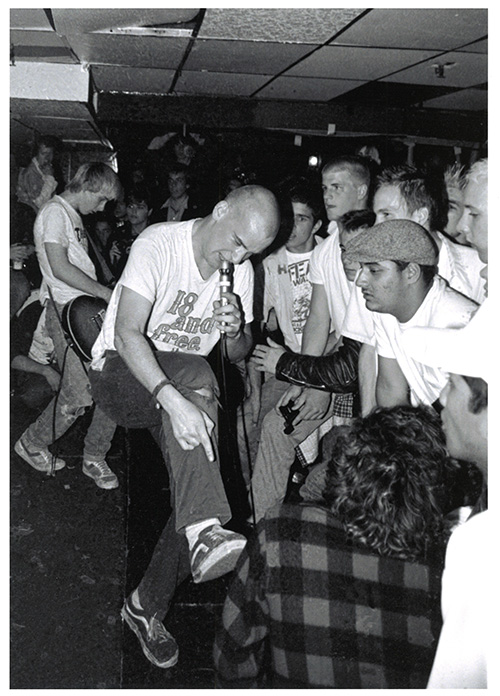

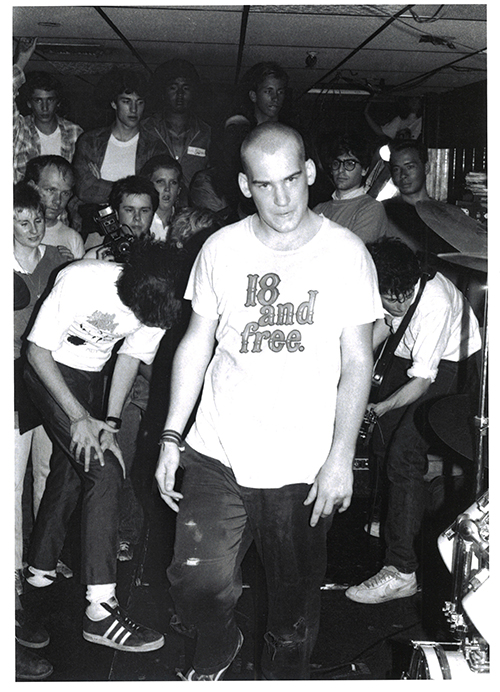

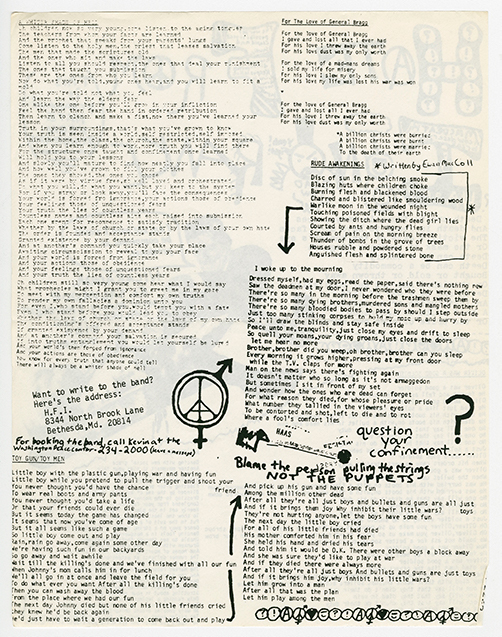

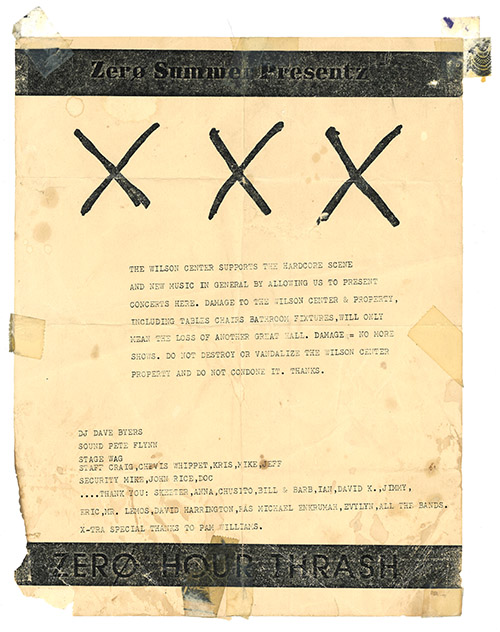

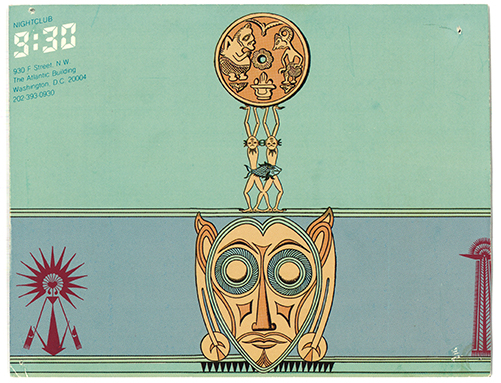

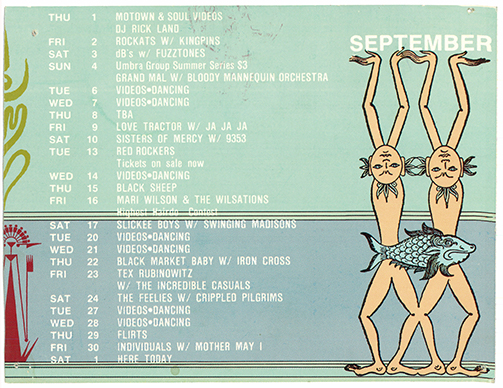

Towards the end of 1982, the future of hardcore shows at the 9:30 Club was uncertain, due to violence and property damage at concerts. Following a community meeting that included members of Minor Threat, WMUC-FM (the University of Maryland's campus radio station), and 9:30 Club staff, among others, the club promoted a series of Sunday hardcore matinee shows in 1983. The matinee concert on January 2 featured Minor Threat, the Faith, and the recently formed Marginal Man.3, 4 Comprised of guitarist Kenny Inouye, bassist Andre Lee, and former Artificial Peace members Mike Manos, Pete Murray, and Steve Polcari, Marginal Man employed a two-guitar lineup which, alongside the band’s stylistic variety and textural contrasts, put them at the scene's vanguard. As more bands formed and the community grew, additional venues hosted punk concerts in 1983, such as the Lansburgh Cultural Center, Oscar's Eye, and Space II Arcade.5 Likewise, new fanzines proliferated in 1983, with titles like Truly Needy, Thrillseeker, Zone V, DCene, Brand New Age, and several others documenting the scene in increasing detail.

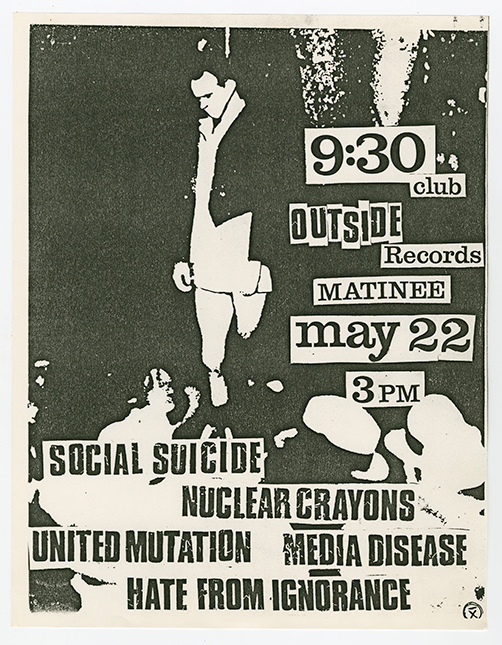

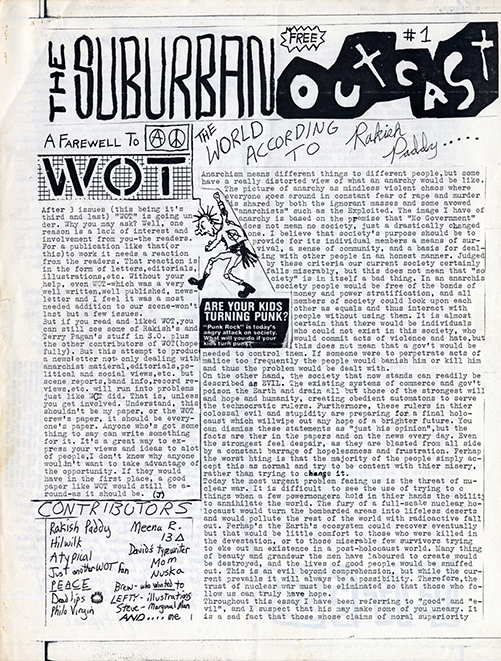

Marginal Man was not alone in its efforts to broaden the D.C. sound beyond what was then labeled "thrash" by some but is now broadly referred to as "hardcore." Nuclear Crayons, which formed in 1981, performed regularly in 1983, their theatrical and dissonant approach would later be identified as an outlier and influence in the queercore scene.6, 7, 8 Vocalist Lara Lynch had launched a new record label, Outside, noting that "we're aiming to get the local bands that Dischord won't take. The Georgetowners seem to think that their bands are the only ones worth recording."9

...

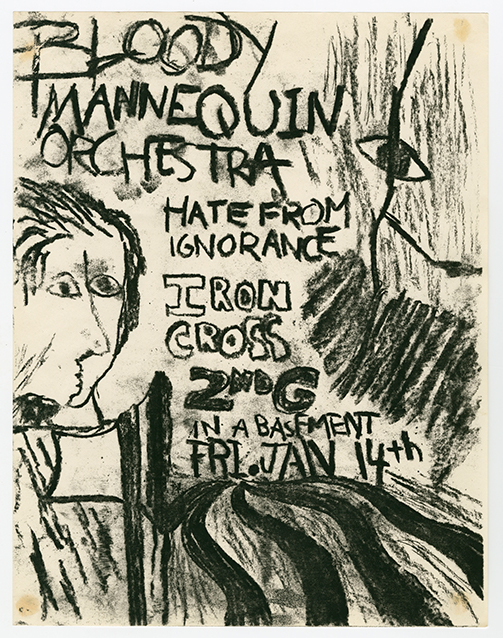

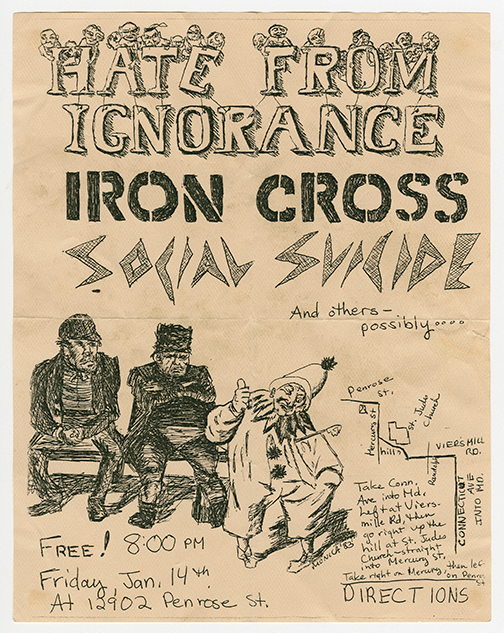

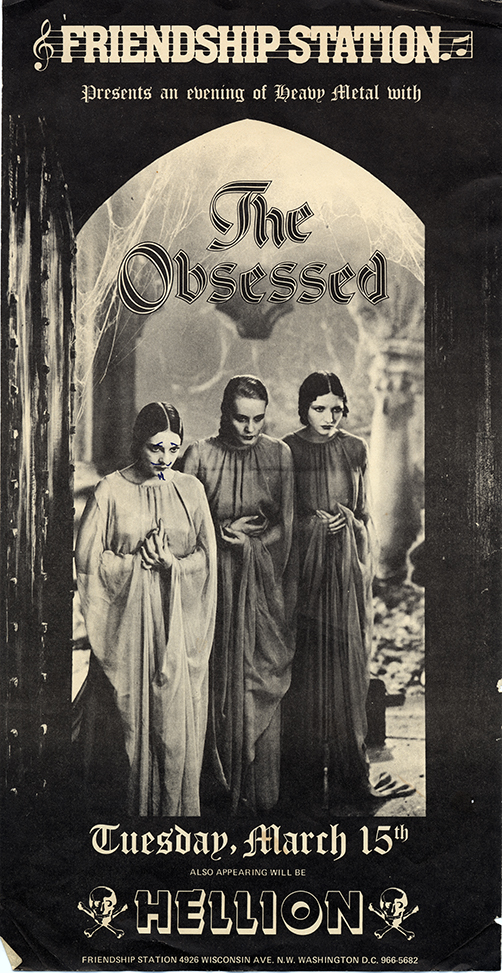

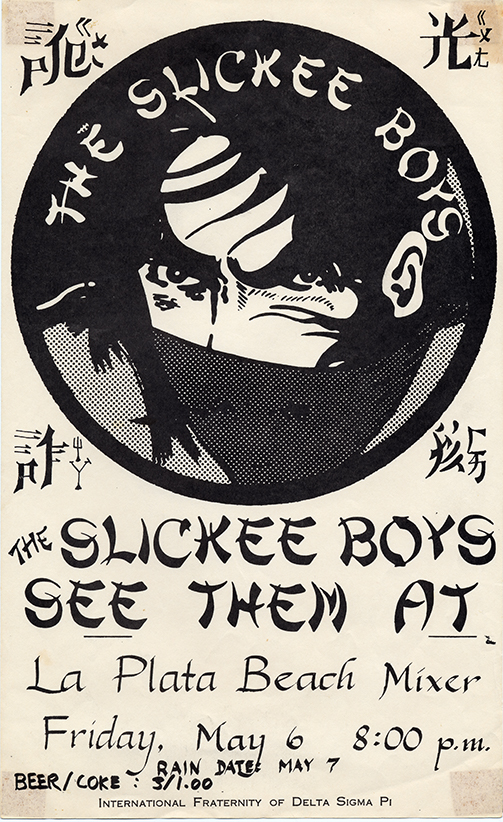

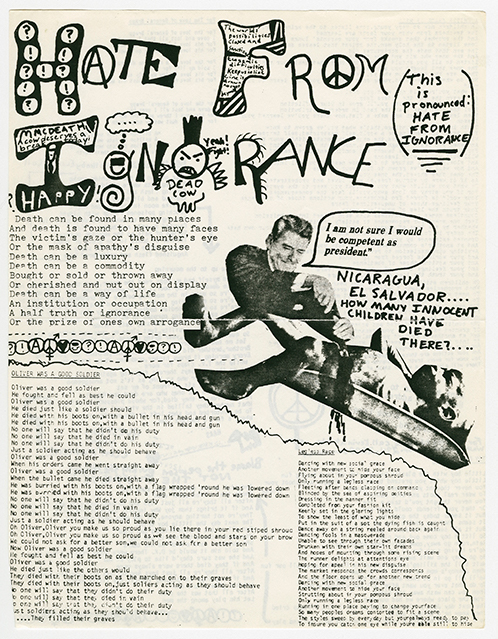

Following up on the 1982 release of Nuclear Crayons' Nameless EP, Outside Records issued the Mixed Nuts Don't Crack compilation in 1983, a crucial snapshot of many of the D.C. punk bands that had not released music on Dischord. Nuclear Crayons were joined on the compilation by Media Disease, Hate From Ignorance, Chalk Circle, Social Suicide, and United Mutation (members of whom would launch their long-running record label, DSI, in 1983). Fountain of Youth was another new label to join the scene during this period, releasing an interesting cross-section of music from the D.C. scene. Velvet Monkeys, Artificial Peace, Black Market Baby, and Government Issue all worked with the label this year, with Dischord co-releasing the latter’s Boycott Stabb EP.

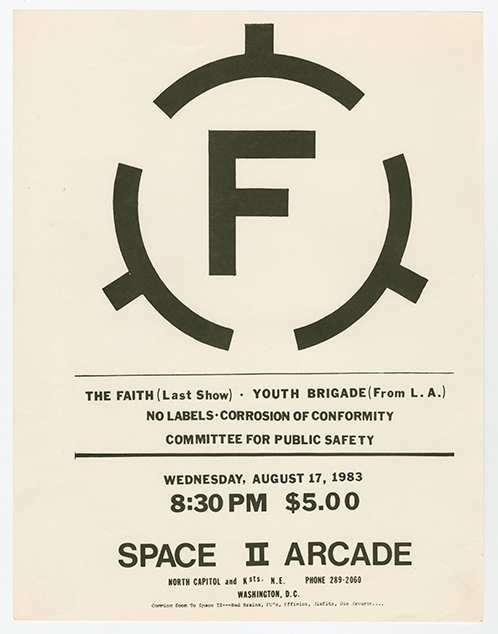

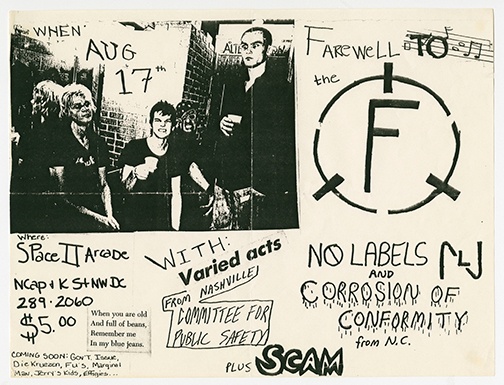

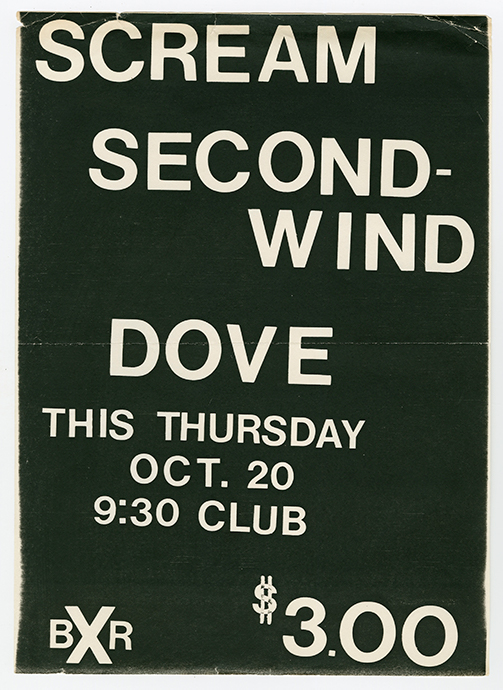

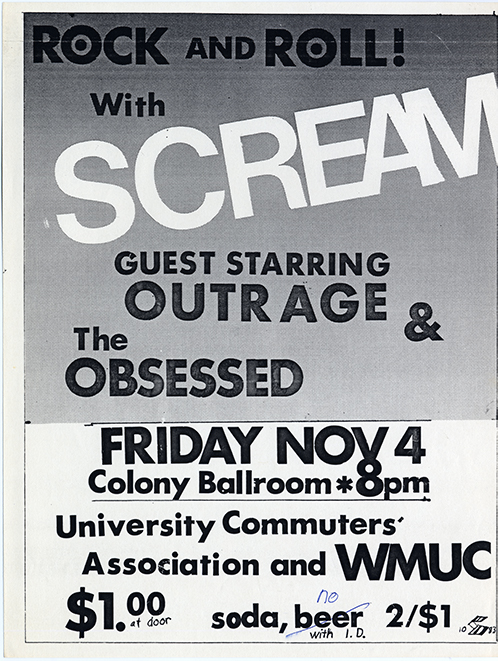

Dischord struggled to keep up with the demand for its earlier releases, but was still able to add a few new titles to its discography in 1983. The Northern Virginia hardcore band Scream released Dischord’s first full-length album, Still Screaming, while Minor Threat released another landmark EP, Out of Step. The Faith, having expanded to a quintet with the addition of second guitarist Eddie Janney, followed up their split LP with Void with the Subject to Change EP, which Ian MacKaye would cite years later as one of his favorite Dischord releases.10 Ever prolific, Dischord also collaborated with R&B Records to co-release a self-titled EP by Double-O and with DSI to co-release United Mutation’s Fugitive Family EP. Maximum Rocknroll dubbed Fugitive Family “a truly amazing record” with “the scariest vocals I’ve heard in a long time.”11

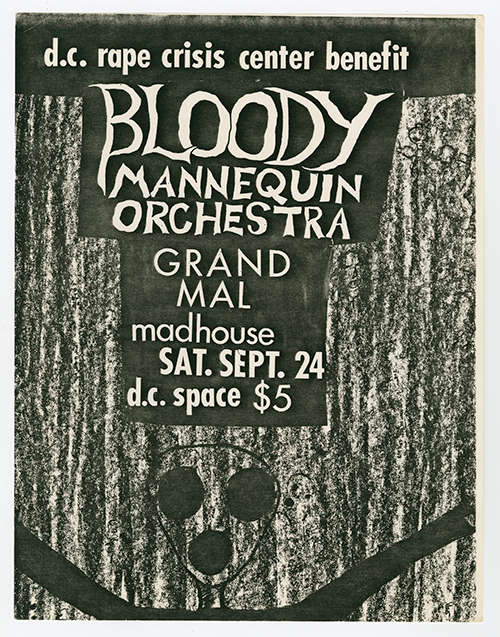

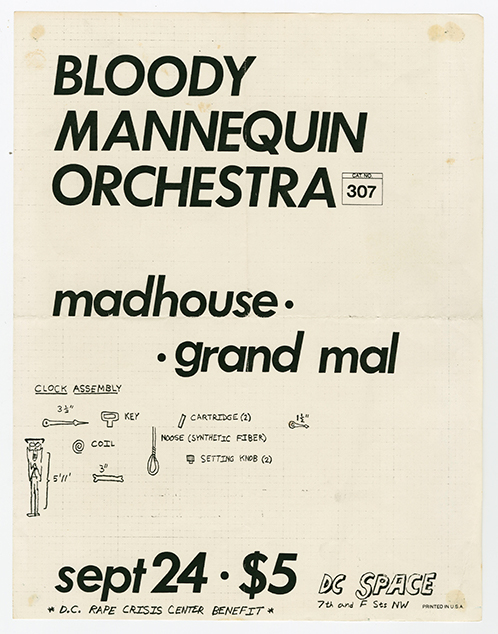

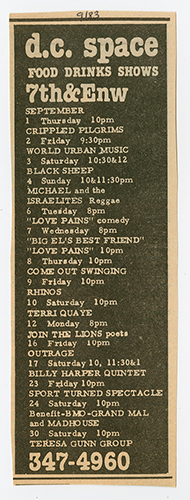

The D.C. punk scene was about more than hardcore in 1983, despite the burgeoning national profile of Dischord and Minor Threat. Two former members of Hate from Ignorance, vocalist Monica Richards and bassist Eugene Bogan, joined with drummer Danny Ingram (of Social Suicide, Youth Brigade, and the Untouchables) and guitarist Norman van der Sluys to form Madhouse, who worked outside of the dominant hardcore sound. Madhouse was often the recipient of what band members considered unfair comparison to goth groups like Siouxsie and the Banshees, which they felt was largely due to being one of the few bands in the scene with a woman at the front.12 They were a major presence in the scene during this period, despite not fitting neatly into what had become musically common for the scene. In an interview with DCene (co-edited by future Shudder to Think bassist Stuart Hill), Ingram and Richards described their desire to transcend the calcifying norms of hardcore punk:

Ingram: We want to have a unique sound…

Richards: Like ourselves.

Ingram: We don’t want to sound like the 20,000 or so “thrash” bands. I hate the term thrash and I hate the term hardcore. Anyone that walks up to me and says “hey do you like hardcore music?,” I just automatically assume that they don’t have enough intelligence to tie their shoelace. We’re trying to do something a bit different, without compromising our integrity.13

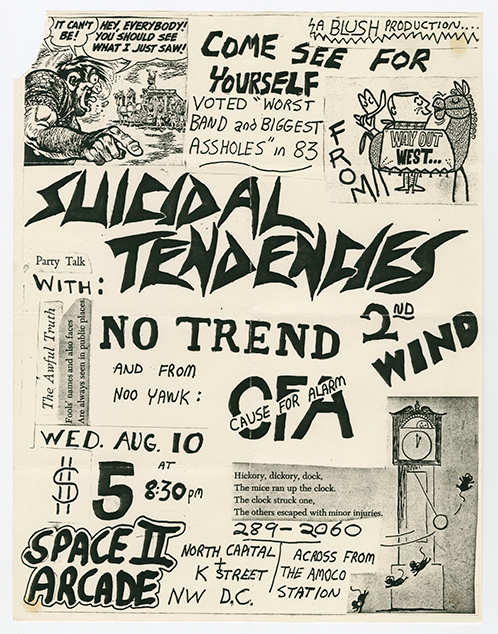

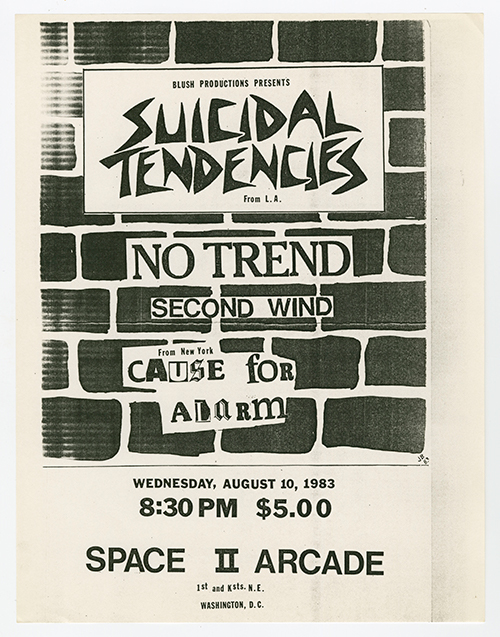

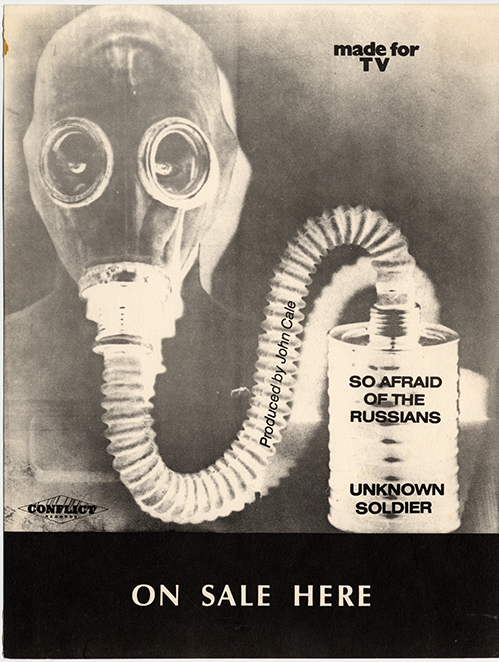

Much as Psychodrama was the hardcore scene’s brackish foil in 1982, a new band stepped up in 1983 to take that role. No Trend materialized from the distant D.C. suburb of Ashton, Maryland with the Teen Love EP and the Too Many Humans… LP, which they released on their own eponymous record label. Harsh, hostile, and atonal, the group “proudly describe[d] its music as ‘unbearable’,” according to The Washington Post14. No Trend’s identity dripped with resentment and spite. Band members took to trolling the Dischord scene by stuffing fliers that said “No Trend, No Scene, No Movement” into the vending machines that the straight edge punks routinely bought their sodas from in Georgetown.15 The band soon found no shortage of enemies. “No Trend, what a fucking joke,” Madhouse drummer Danny Ingram seethed. “I hate No Trend and it has nothing to do with their music. I hate them personally.”16

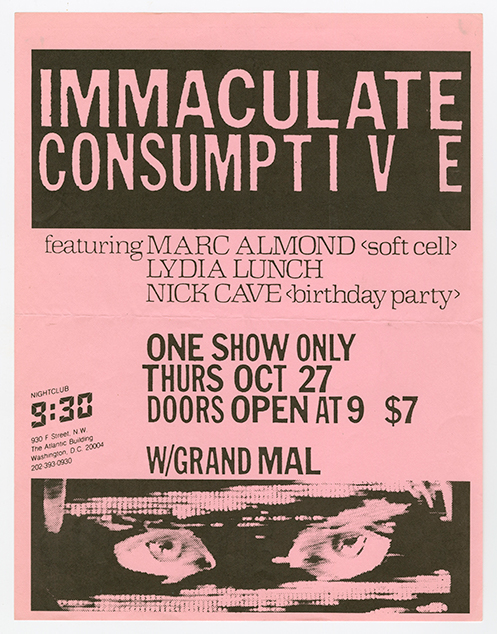

Conversely, they also built a small following of punks who appreciated the pushback on their more popular elements of the D.C. scene. In the years ahead, the group would perform with several of the national punk scene’s leading musicians, like Dead Kennedys, Lydia Lunch, and Butthole Surfers. Writer and musician Sam McPheeters referred to No Trend as “the ultimate DC outsiders,” noting that, while the band is generally remembered for their antipathy toward the hardcore scene, “what they should be remembered for is their unrelenting misanthropy.” To McPheeters, the group’s music and lyrics resonated deeply, speaking to his “young adult fears” of “the unknown,” “annihilation,” and “insanity.”17 Never mind inter-scene squabbling, under the shadow of the Cold War and the growing threat of nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union, No Trend’s scabrous music could reasonably be considered the most rational response possible.

In histories of the scene, 1983 often centers on the final tour and breakup of Minor Threat. In the year prior, Minor Threat begrudgingly began contending with their new status as the figurehead of the D.C. scene and as one of America’s leading hardcore bands. By 1983, the personal credo laid out in their song “Straight Edge” had become a nascent clean living movement popular in Boston and elsewhere, centered on strict abstinence of psychoactive substances and hedonistic behavior. The straight edge movement had gotten to the point where members of Minor Threat felt the need to reiterate their intentions with the song, as this excerpt from an interview in the D.C. punk zine Brand New Age demonstrates:

Ian MacKaye: "Straight Edge" is an anti-obsession, pro-positive song and it’s not telling people what to do. It’s not a set of rules. "Straight Edge" is not a movement. "Straight Edge" is just an idea.

Jeff Nelson: Or, at least, we’re not the leaders of the movement, if there is one. We’re not intent on leading it at all. It’s just one of our songs.18

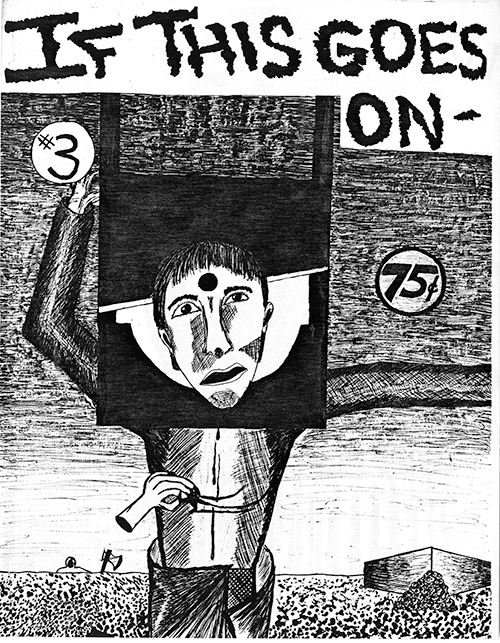

This new standing was paired with increased criticism, often fueled by some D.C. punks' perceptions that Minor Threat dominated the scene at the expense of other acts. The success of Minor Threat broadened an unintentional gulf between band members and other participants in the scene. When Sharon Cheslow and Colin Sears interviewed Minor Threat for their fanzine, If This Goes On, MacKaye reflected on his frustrations with the expectations put on Minor Threat as they grew in popularity and worked to maintain their status as a D.C. band foremost:

See, the point is now that it used to be we were buddies. We could all talk, everyone in the scene or whatever. But it's gotten big, fine, but there’s no way I can talk to everyone. There's no way I can make everybody happy and I wish I could make everybody happy, but I can’t. The lack of communication is like really, really twisted and misinterpreted and fucked up, as far as our relationship with Washington. We still maintain we’re a Washington band. We’re proud as shit of being part of Washington.19

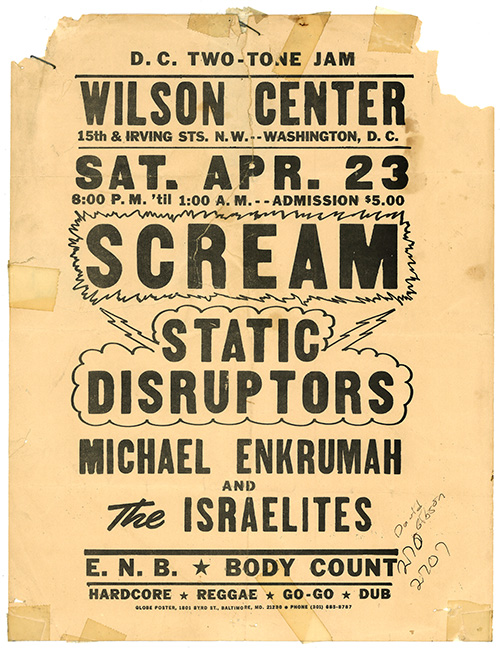

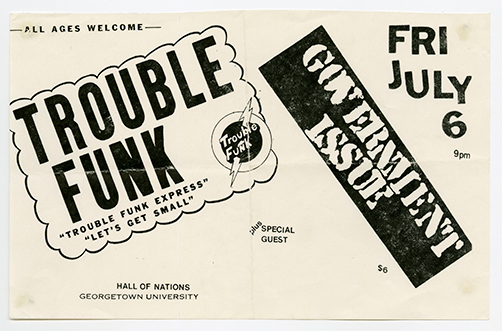

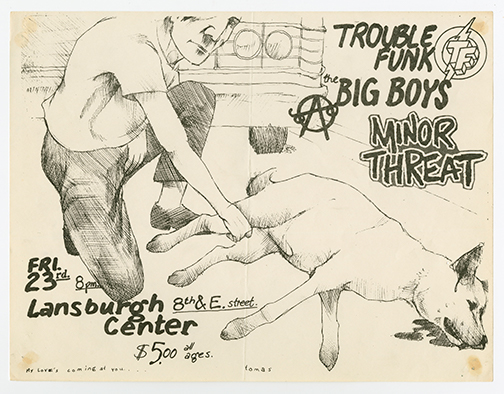

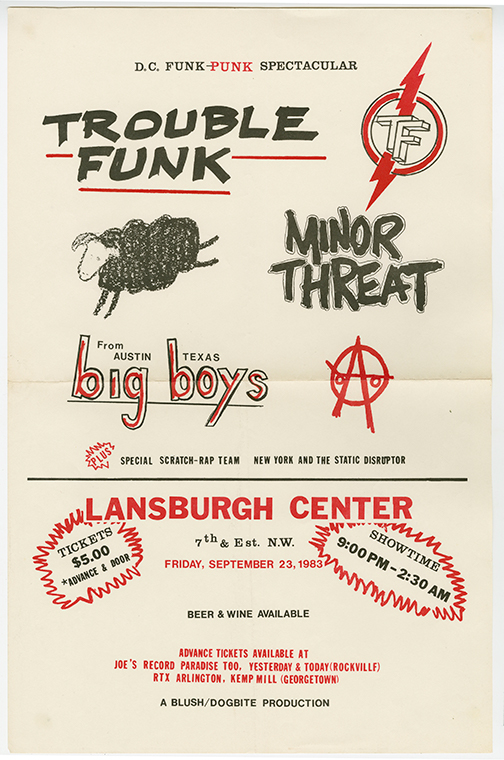

Following Minor Threat’s national tour, the D.C. punk scene was among the most prominent in the United States. Minor Threat continued to serve as an example of a music forged in idealism and committed to accessibility through affordable, all-ages shows. The group managed its own touring, promotion, merchandise, and recordings, demonstrating that punk bands did not need to move to a large media center like New York or Los Angeles, nor work with a major record label, to succeed and reshape the subcultural landscape. On September 23, Minor Threat played its final concert, sharing the bill at the Lansburgh Cultural Center with Big Boys—a funk-inspired punk band from Austin, Texas who were influential to both skate punk and later queercore artists—and the go-go group Trouble Funk. The night was branded on posters as “The D.C. Funk-Punk Spectacular” and was an early example of the joint punk and go-go concerts that occurred intermittently over the next few decades in the D.C. area.

This show was an important one for both being Minor Threat’s last and also as one of the higher profile points of crossover between two integral sounds of D.C.—punk and go-go. Go-go is a galvanic, percussion-propelled offshoot of funk, which increasingly incorporated elements of hip-hop throughout the 1980s. Eye-catching, Day-Glo posters used to promote go-go concerts were a distinctive hallmark of the go-go community, dotting the city like “fluorescent flags” that “asserted a territory of black economic, cultural and political power,” as author and academic Natalie Hopkinson wrote.20 Pioneered by groups like Chuck Brown & the Soul Searchers, Trouble Funk, and Rare Essence, go-go remains “the beating heart of the ‘Chocolate City.’”21

Another significant development for D.C punk that occurred in 1983 was the break-up of the Faith following their final concert on August 17 at Space II Arcade. While their presence on the scene was brief, the more melodic approach to hardcore that the Faith developed on Subject to Change would become a major influence in the coming years. “I always thought the Faith were the most ‘core’ of the hardcore,” Sonic Youth guitarist Thurston Moore remarked. “Seeing the Faith [in concert] was like seeing Led Zeppelin at Knebworth in ‘79 for me.”22

With both the Faith and Minor Threat defunct, it was unclear which bands might fill the void they left behind. “As far as I’m concerned, everything started going downhill after Minor Threat broke up,” Marginal Man guitarist Kenny Inouye stated. “It’s not the result of them breaking up that made it bad. It was just the timing. Things were getting too big for their own good.”23 Meatmen vocalist and Touch & Go fanzine editor Tesco Vee, concurred somewhat, noting that "1983 felt like the end of something to me.”24 Indeed, the first and most consequential wave of D.C. hardcore was ending, but a new phase of D.C. punk would soon emerge, one creatively and politically more progressive than its predecessor. First, however, the scene would have to navigate what lay ahead: 1984.

Further Listening

Black Market Baby. Senseless Offerings. Fountain of Youth Records, Album.

Double-O. Double-O. Dischord Records/R&B Records, 7-inch EP.

The Faith. Subject to Change. Dischord Records, 12-inch EP.

Government Issue. Boycott Stabb. Fountain of Youth Records, 12-inch EP.

Minor Threat. Out of Step. Dischord Records, EP.

No Trend. "Teen Love." No Trend Records, 7-inch single.

No Trend. Too Many Humans… No Trend Records, Album.

Scream. Still Screaming. Dischord Records, Album.

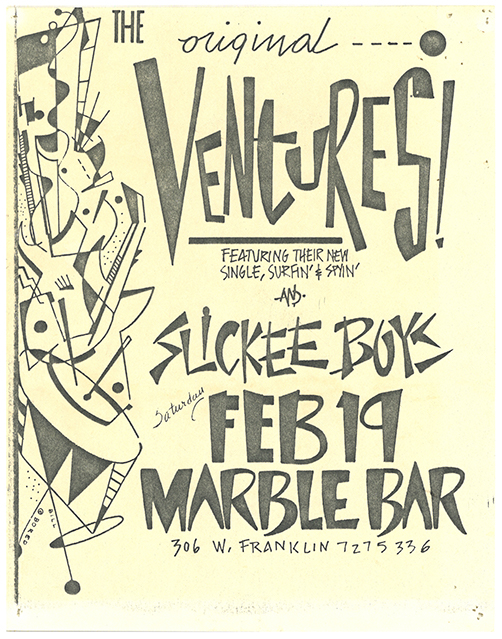

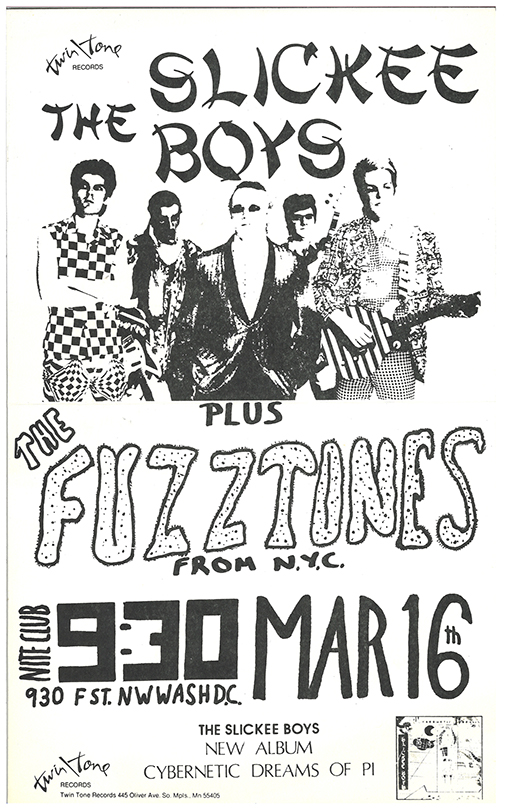

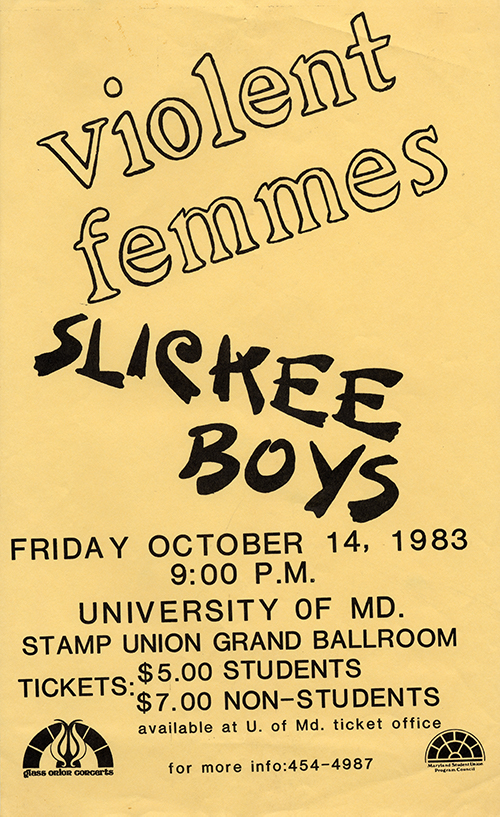

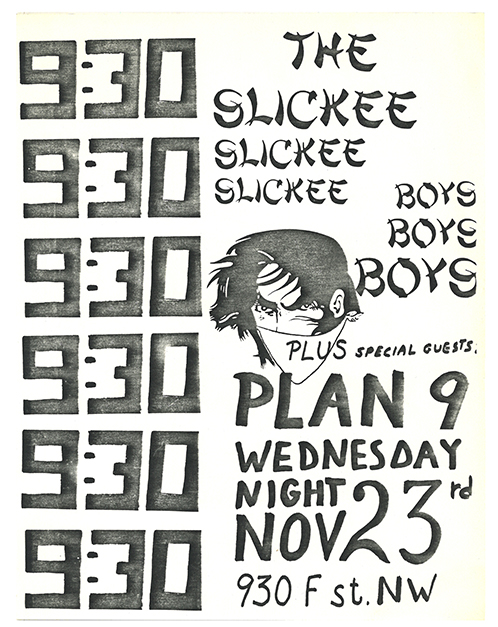

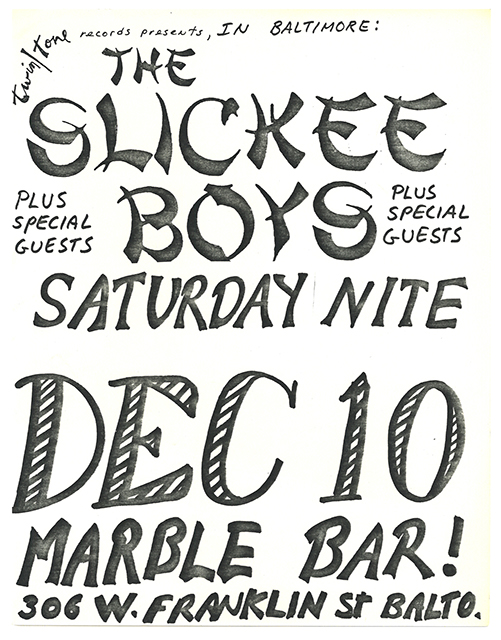

Slickee Boys. Cybernetic Dreams of Pi. Twin/Tone Records, Album.

United Mutation. Fugitive Family. DSI Records/Dischord Records, 7-inch EP.

Various Artists. Mixed Nuts Don't Crack. Outside Records, Compilation album.

Velvet Monkeys. Future. Fountain of Youth Records, Album.

Materials are drawn from the Chris Baronner digital collection on D.C. punk, the Paul Bushmiller collection on punk, the Sharon Cheslow punk flyers collection, the D.C. Punk collection, the D.C. punk and indie fanzine collection, the Kevin Salk collection of D.C. punk photographs, and the Robbie White collection.

Tap or hover over an image to learn more.