When interviewed by Sassy magazine, Nation of Ulysses vocalist Ian Svenonius predicted "I think D.C. will define the '90s." In the early days of 1990, that certainly seemed to be the case.1 By mid-January the FBI, the DEA, and D.C.’s Metropolitan Police Department were working together to set up a sting operation with the goal of catching D.C. Mayor Marion Barry either purchasing or consuming cocaine on camera. The agencies worked to piece together connections stemming from the arrest of Charles Lewis, an associate of Barry’s, at the Ramada Inn Central in December of 1989. They decided to use a former romantic partner of Barry’s to lure the mayor to a hotel room wired with microphones and cameras, where Barry was caught using crack cocaine.2 When images from the setup were made public, the local scandal dominated national headlines.

In the midst of the dual major crises in the District of drug trafficking and murder, Barry’s case became a bellwether touching on race, class, and the role of government. Some decried the mayor as a hypocrite who failed to address major issues gripping the city and took advantage of his office while others saw him as a foundational civil rights leader who had steered the city through the early days of home rule and who was now struggling with an incredibly addictive substance. Over the course of the year, Barry's trial remained at the center of local news, and by November, the face of local politics for over a decade was sentenced to six months in federal prison.3

Barry was succeeded as mayor by Sharon Pratt Kelly, the first African American woman to run a major U.S. city who had won with a campaign using a literal broom and shovel as props, vowing to clean up the city. However in the immediate aftermath of Barry's sentencing, it remained clear how endemic corruption had become at all levels in the city. One tragic example of this was the collapse of the Latin Investment Corporation, which offered banking to its customers—primarily Salvadoran immigrants—despite not having a bank charter or federal deposit insurance. When it went bankrupt, it took with it the savings of over 2,500 people, totalling around 13 million dollars.4

...

One possible indicator that D.C. residents were becoming inured to the violence around them occurred when local Fox affiliate WTTG canceled City Under Siege, a television program highlighting drug-related violence in the District. “It's not clear a single-issue show like this is ever going to have a happy ending," a station executive reasoned. “We wanted to go onto broader issues in the community, as well." The previous year had seen 437 murders—the highest annual total in D.C.’s history—but the statistics would only worsen in the immediate years ahead. Reflecting on the program’s cancellation and the stagnation of solutions to the persistent issue, Washington Post journalist Michael Isikoff wrote that there was “a growing consensus among law enforcement officials and policymakers that there are no shortcuts in uprooting the drug trade—and that, in fact, the solutions ultimately lie in addressing the social conditions that spawned drug use.” 5

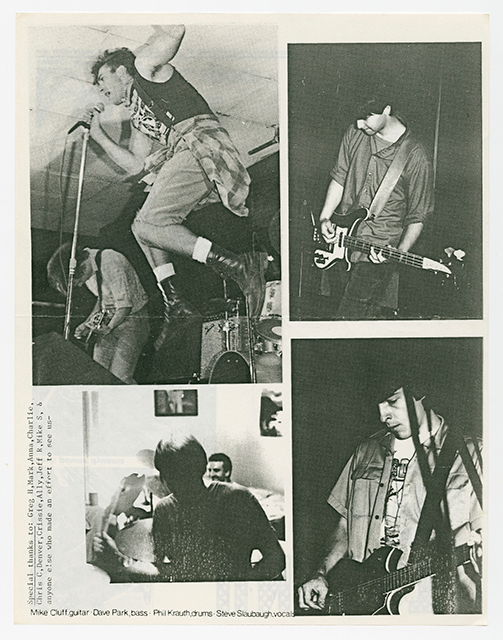

The punk community reflected the weariness and anger felt by many in the District. A concert review by Ron Winters (also the guitarist/vocalist in the recently formed Branch Manager) in Sweet Portable You fanzine included a description of the ambulance and medical examiners that raced down 16th Street NW as he waited outside the show. “The clock ran out on another murder victim, no doubt,” Winters mused gloomily.6 While the city’s punk subculture had often seemed insulated from much of what occurred in greater D.C. throughout the early 1980s, by the turn of the decade, the reality of the toll that drugs, violence, and underfunded social services had taken on the people that lived in the District was unavoidable.

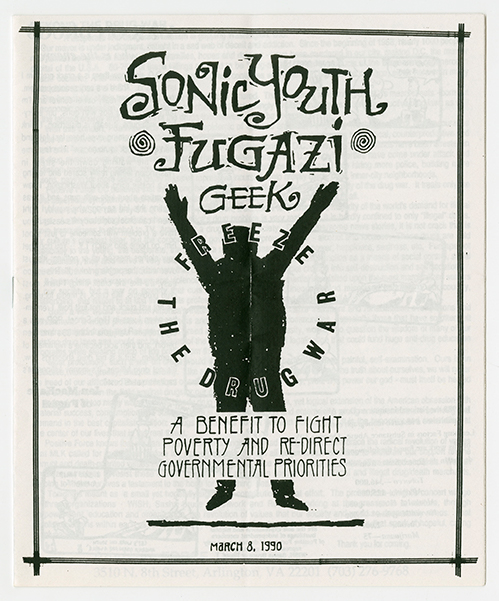

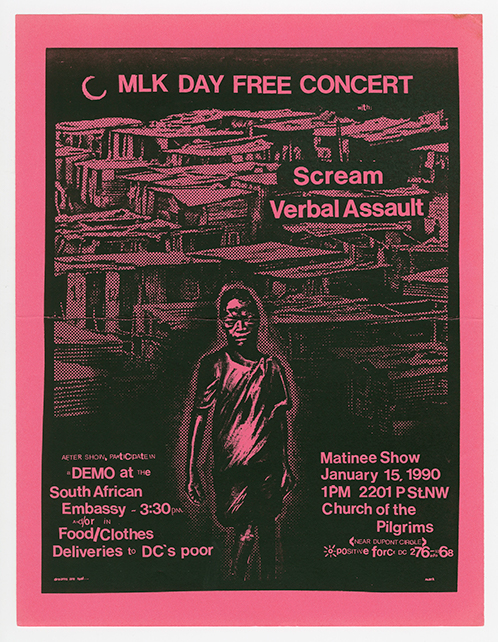

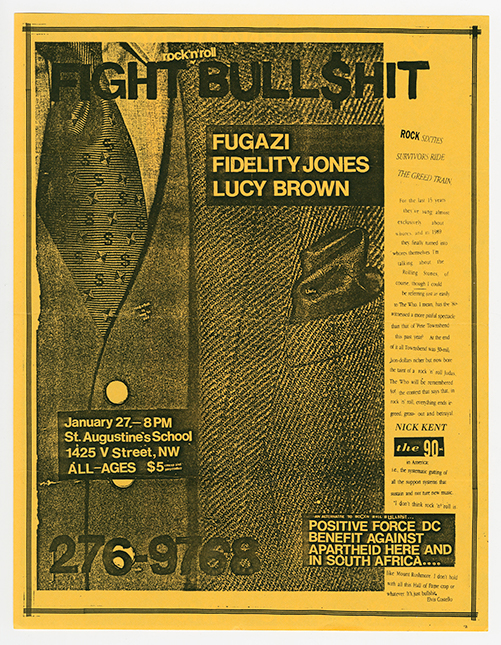

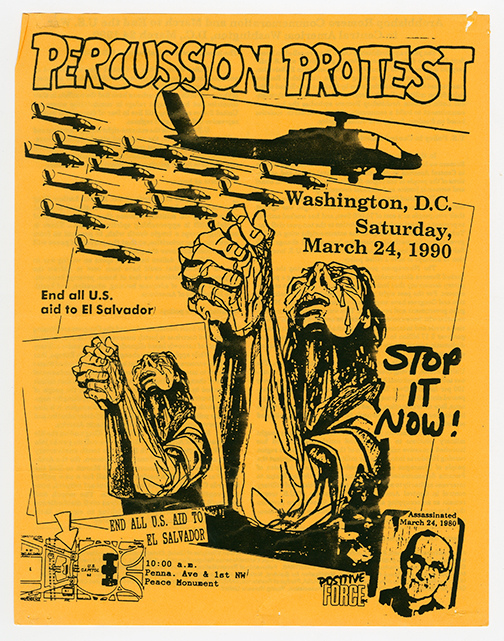

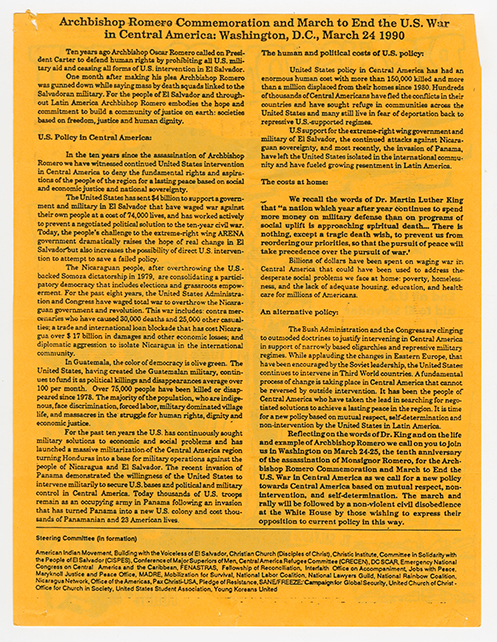

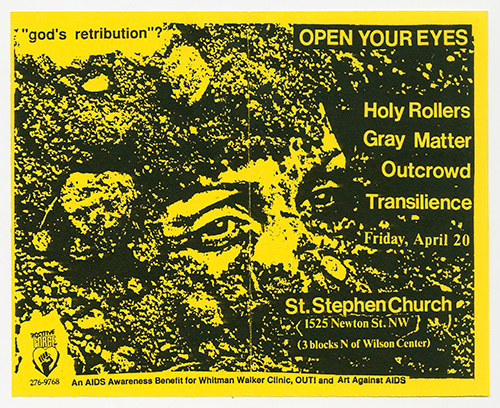

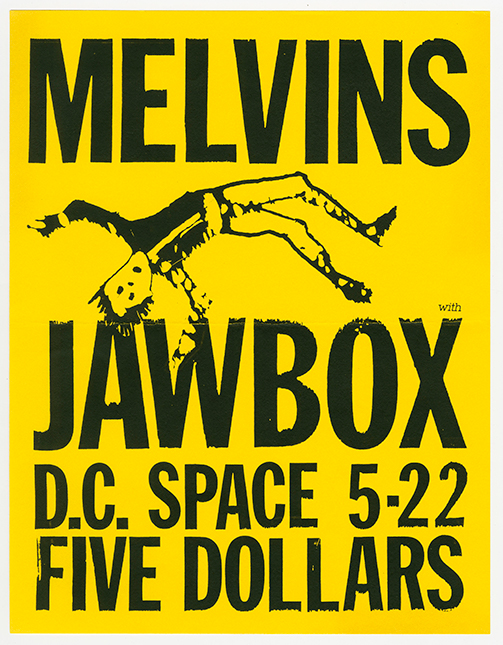

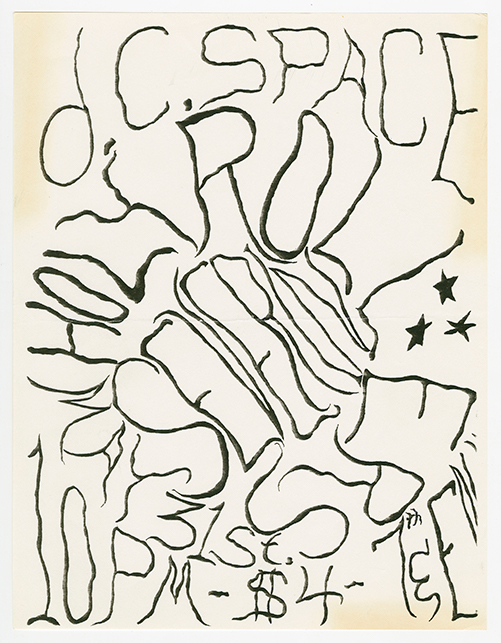

The punk scene remained focused on what it saw as the ills of American policy. Concert fliers for the year highlight how benefit shows increasingly became a way for the community to push back in a tangible way, raising both awareness of issues and funds for charities. Positive Force continued to organize concerts and protests related to a range of issues, including the ongoing global apartheid—a January 27th show featuring Fugazi and Fidelity Jones—and the fight against AIDS, with a show headlined by Holy Rollers and Gray Matter benefitting D.C.’s Whitman-Walker Clinic. As with before, fliers were a primary medium for voicing dissent, with one Positive Force handbill for a March 24th percussion protest against the continued United State military intervention in El Salvador reading:

A Fundamental process of change is taking place in Central America that cannot be reversed by outside intervention. It has been the people of Central America who have taken the lead in searching for negotiated solutions to achieve a lasting peace in the region. It is time for a new policy based on mutual respect, self-determination, and non-intervention by the United States in Latin America.

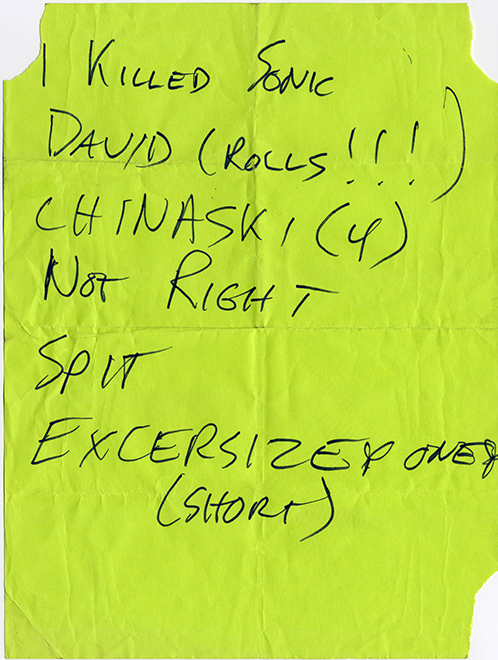

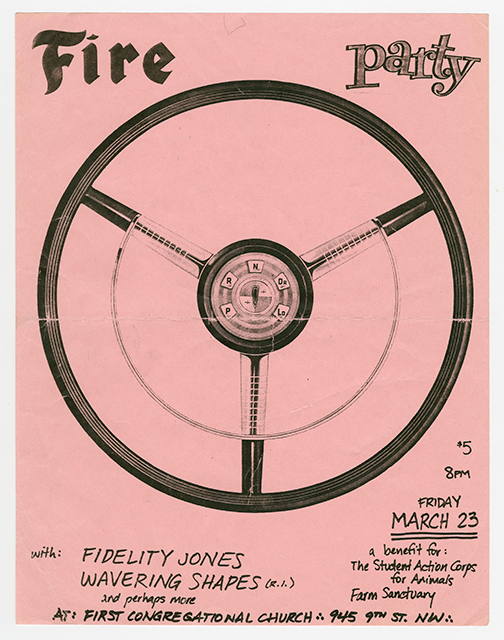

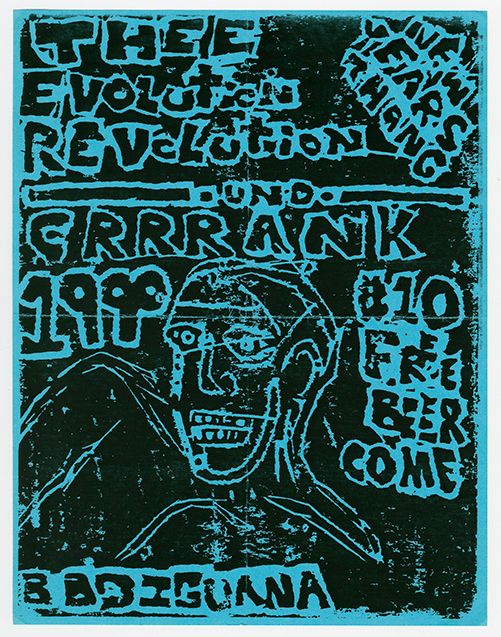

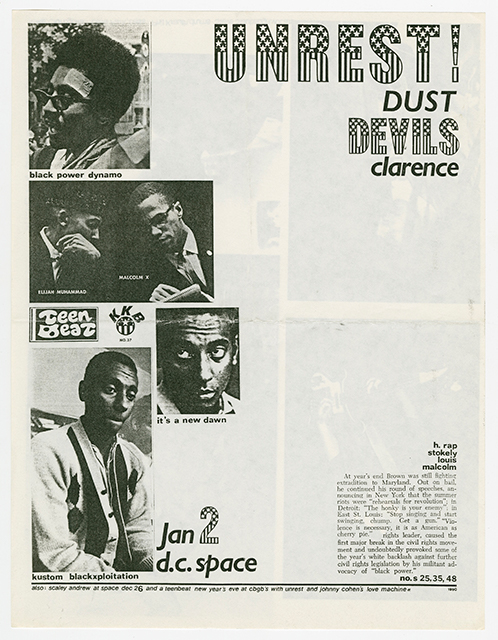

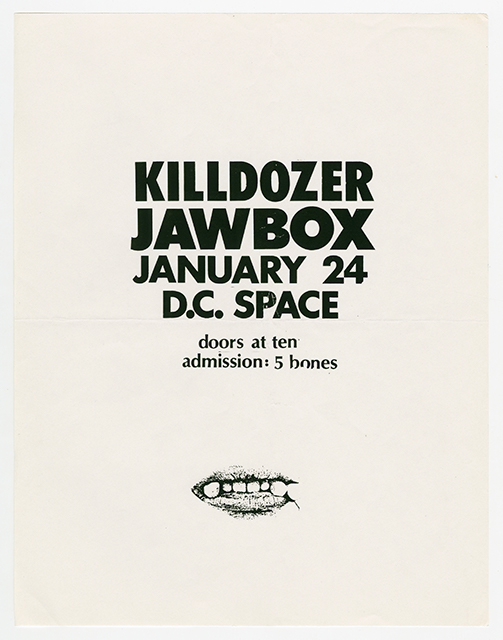

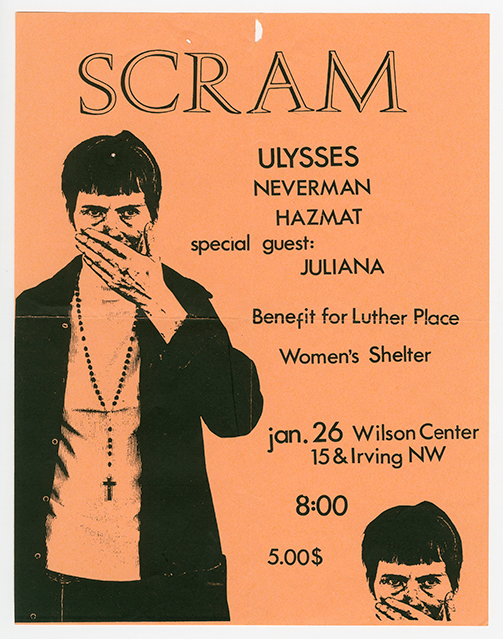

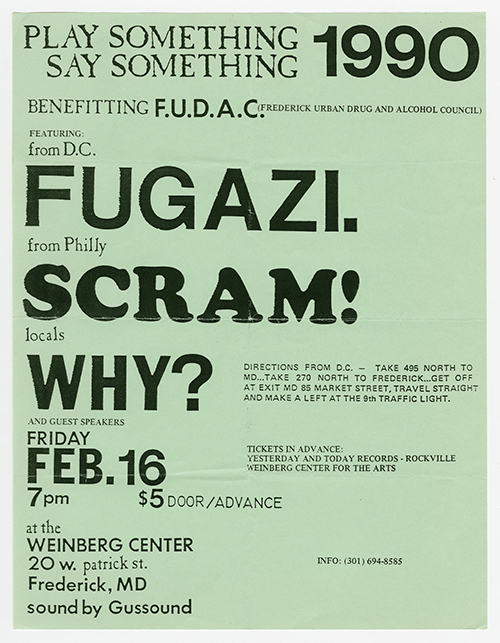

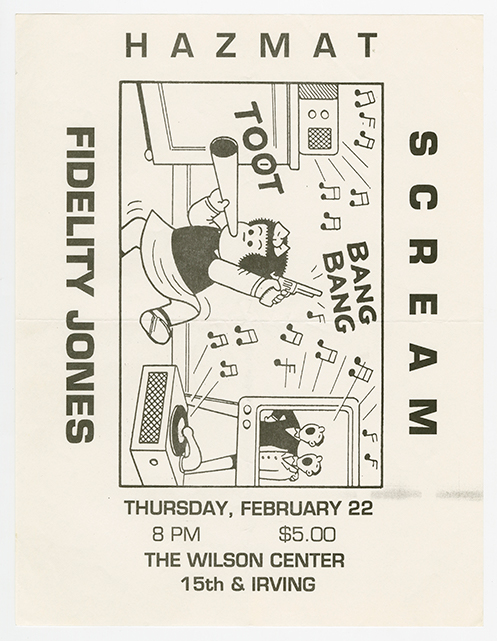

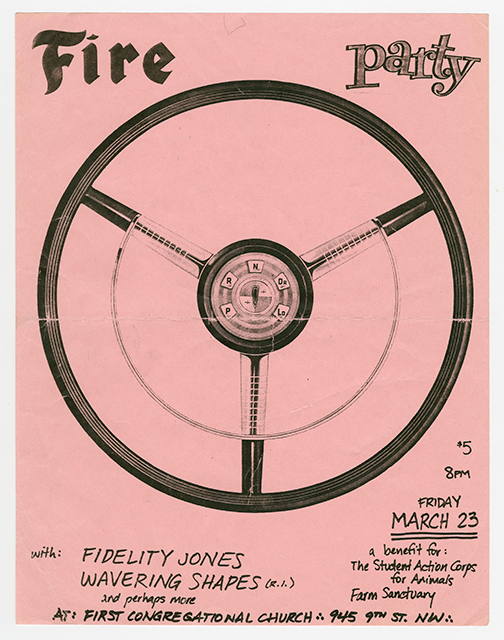

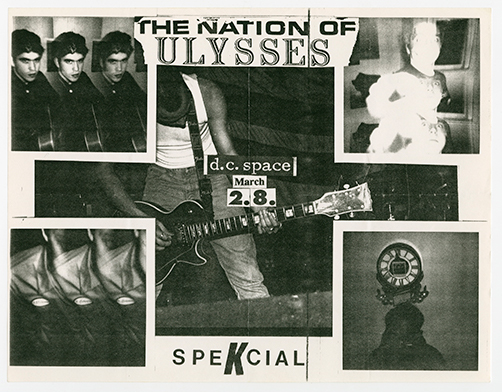

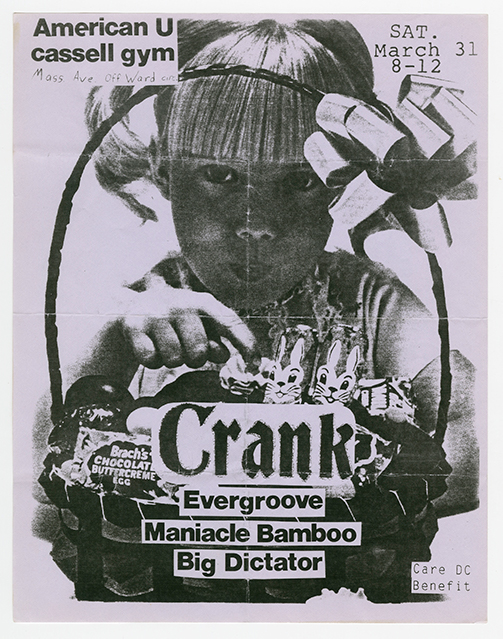

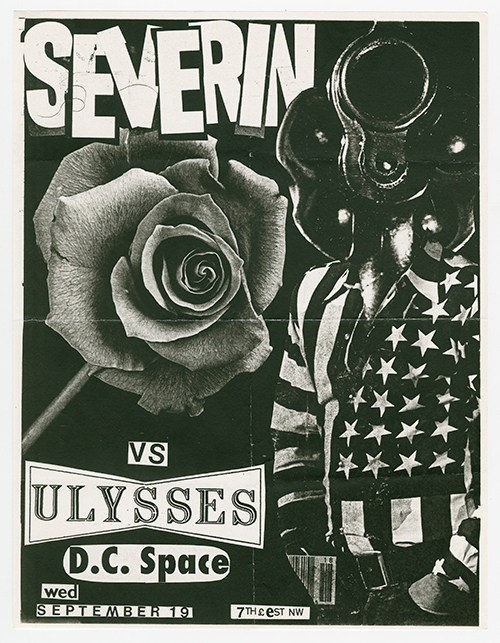

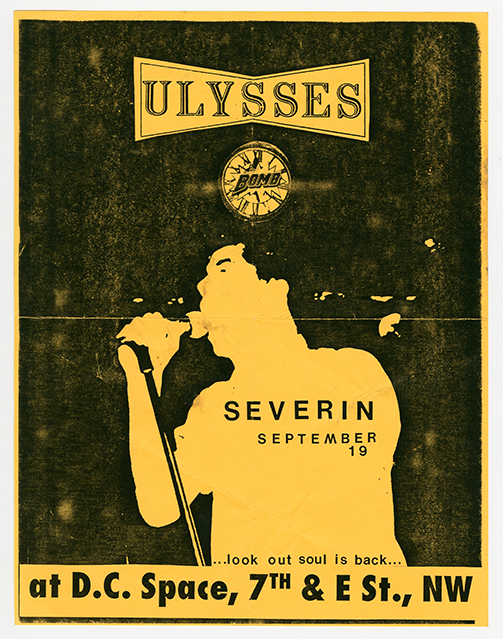

Benefit shows had extended out beyond those just organized by Positive Force. Fliers from 1990 highlight the diversity of causes addressed by the scene, whether it was a Ulysses and Hazmat benefit for the Luther Place Women’s Shelter on January 26th, Fugazi’s show in Frederick, Maryland on February 16th benefitting the Frederick Urban Drug and Alcohol Council, or Fire Party’s benefit for the Student Action Corps for Animals on March 23rd. The political activity and ties of the scene through shared performance spaces or through common media, such as zines, became a central point of cohesion, as opposed to unity achieved through similar music aesthetics. Whereas a distinctive style was easier to determine in earlier waves of D.C. punk, the scene in 1990 was polyvalent through a diversity of sounds and, increasingly, record labels. Bands were often proving to be punk in spirit and action rather than by a readily identifiable sound, while more labels developed to document them.

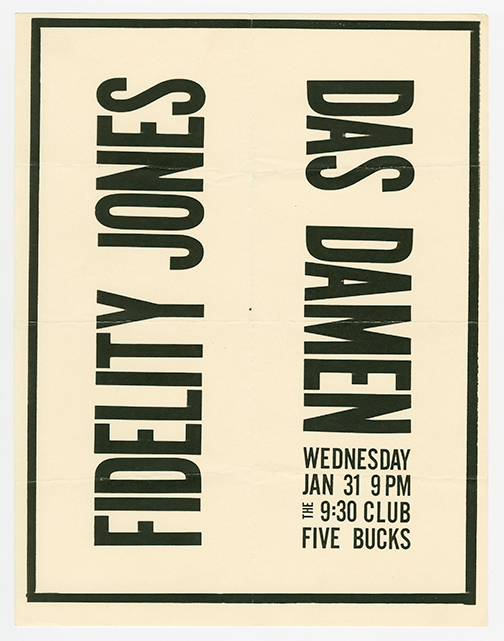

Fidelity Jones, fronted by Onam Emmet (then known as Tomas Squip) of Beefeater, was an example of a group that ignored common punk musical signposts, instead channeling the liberated energy of the punk ethic into the songwriting and arranging process. The band’s Venus On Lovely single from 1990 included “Destructor,” which noticeably eschewed established punk sounds through its opening Hammond organ swell and its use of Manjira (an Indian hand cymbal often used in religious contexts).7 The group would disband that spring, however, leaving behind an album, a single, and a track on the State of the Union compilation.

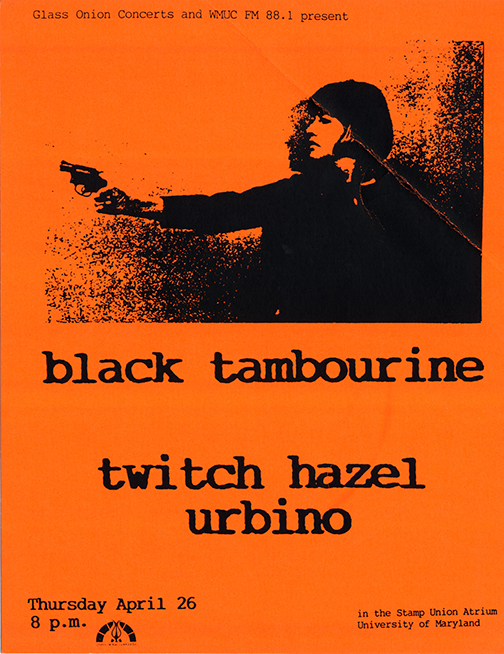

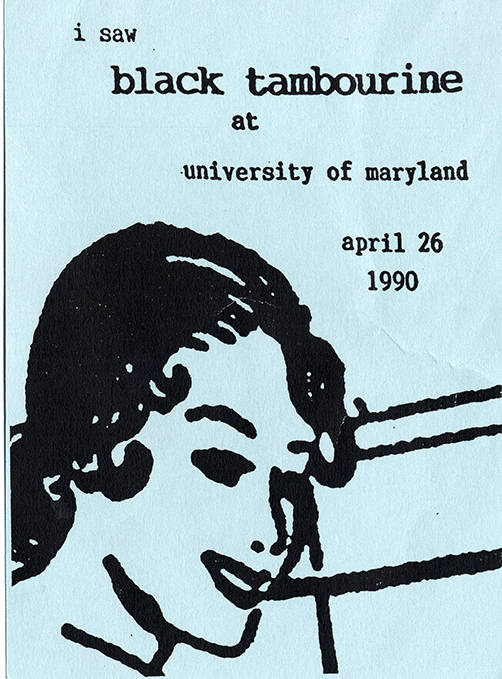

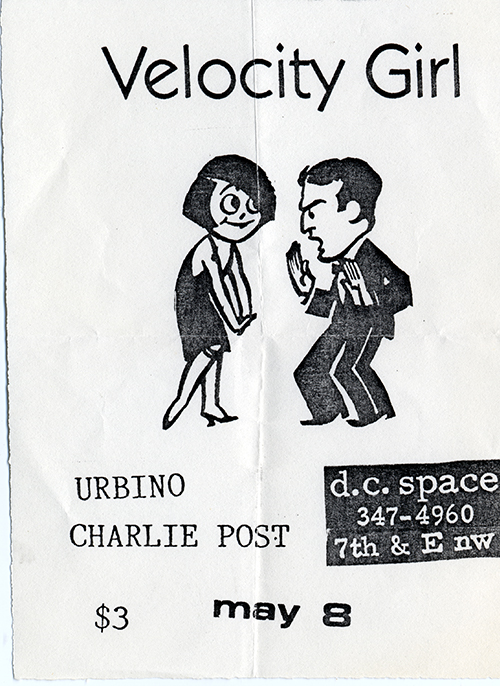

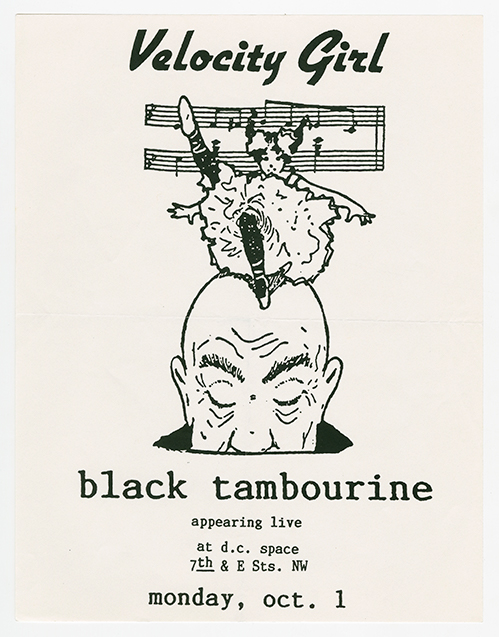

Coming from a different corner of the scene, Velocity Girl released their debut single, “I Don’t Care If You Go,” this year. That song, along with “Always” on the flip side, featured a melodic wall of sound that drew on the burgeoning shoegaze style popular in the United Kingdom, with the vocals draped over a bed of distorted, hazy guitars. The group would soon be at the forefront of D.C.’s overlapping indie rock and indie pop scenes, which became a driving part of the city’s punk community in the 1990s.

Holy Rollers formed a year earlier with drummer Maria Jones, formerly of Broken Siren, alongside Joey Aronstamn and Marc Lambiotte, who were both members of Grand Mal earlier in the decade. Holy Rollers’ debut full-length release on Dischord, As Is, showed a variety of influences, from funk (which was becoming ubiquitous in rock writ-large), psychedelic rock, metal and, certainly, their peers in the D.C. scene like Fugazi and Soulside. The band grumbled in retrospect about the production of As Is, with Aronstamn noting that it “didn’t capture our live sound [...] The basic tracks just didn’t have the power I felt.” Aronstamn was more upbeat about the bonds within the community, however. “The thing that’s cool about D.C. is that people want to do good,” he told Who Cares fanzine. “Not like other places where people are just waiting for you to fuck up. Whereas, here, there’s a lot of support. Not just for bands, but for people, too.”8

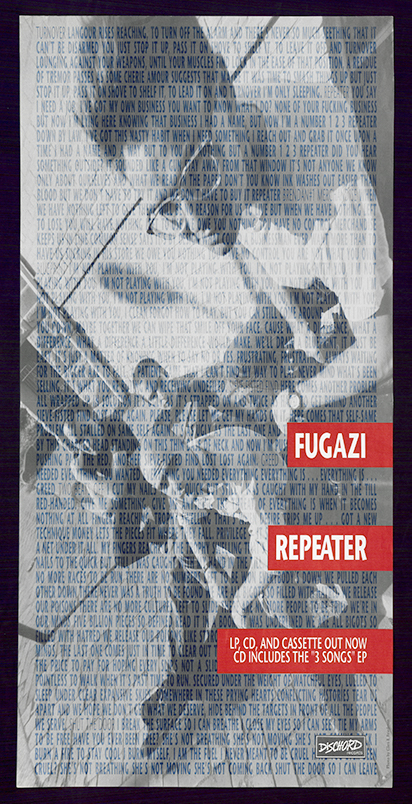

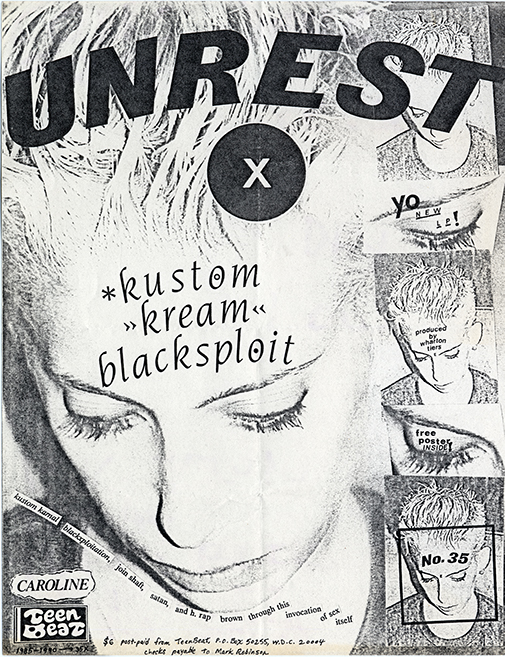

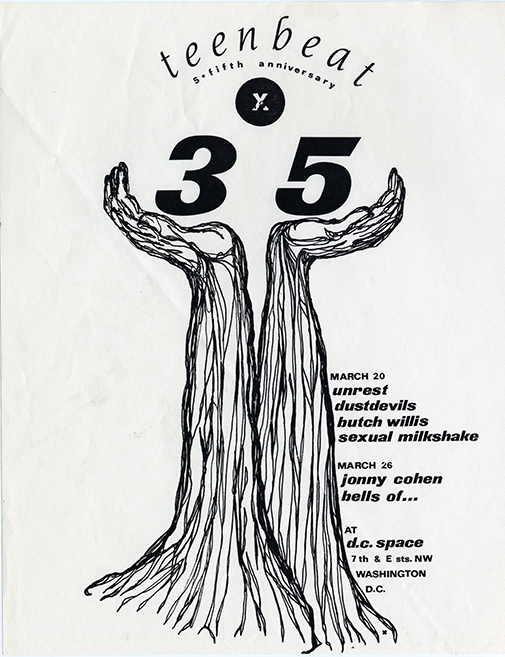

While Dischord remained a defining voice of the scene—Fugazi’s first full-length album, Repeater, was released in 1990 and raised the band’s profile even higher—new labels emerged and others expanded their footprint. As prominent as Dischord was, there had always been other record labels releasing important music from the community—Fountain of Youth, Dacoit, DSI, Limp, and Outside were just a few. The crop of complementary labels in 1990, however, would have a broader impact than any that came out of the scene previously. Teen-Beat, formed by Mark Robinson of Unrest in 1984, continued to add to its eccentric discography in 1990 with releases from, among others, Robinson (as Mark E. Superstar), and Scaley Andrew, as well as out-of-town bands like New York City’s Dustdevils, Harrisonburg, Virginia’s Sexual Milkshake, and California’s Vomit Launch. Teen-Beat also issued the prank call collection, The Tube Bar, featuring album art that affectionately satirized Dischord’s seminal Flex Your Head compilation from 1982.

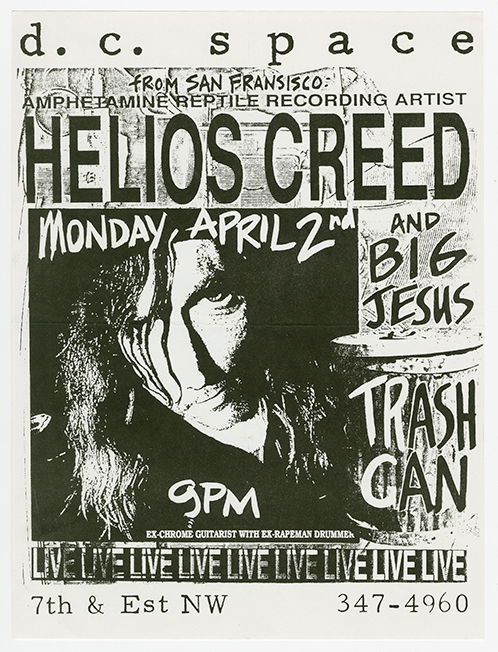

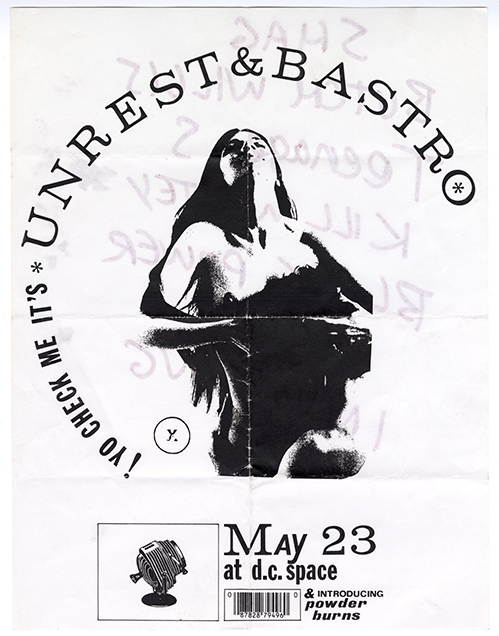

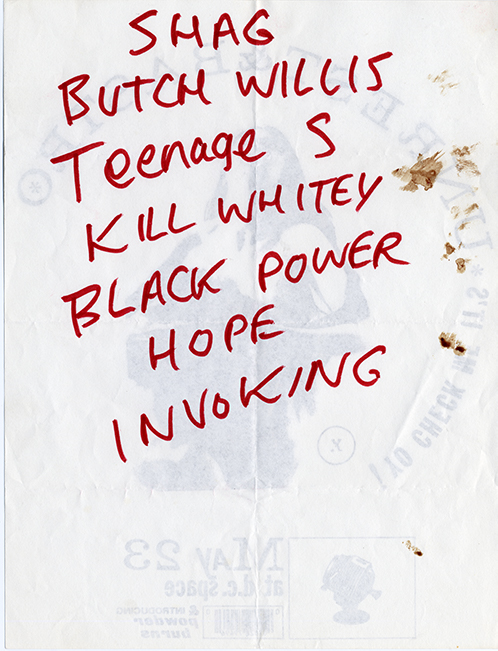

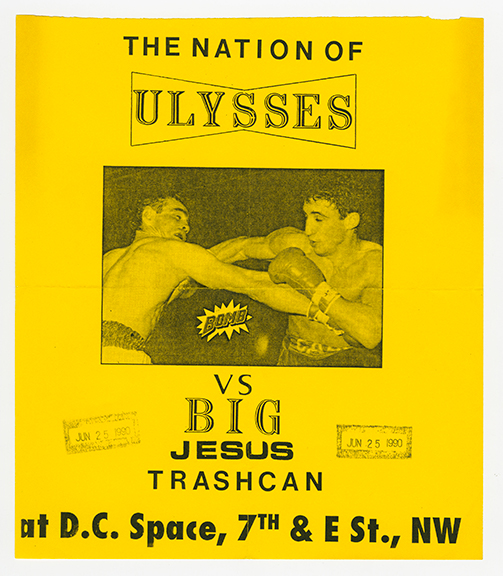

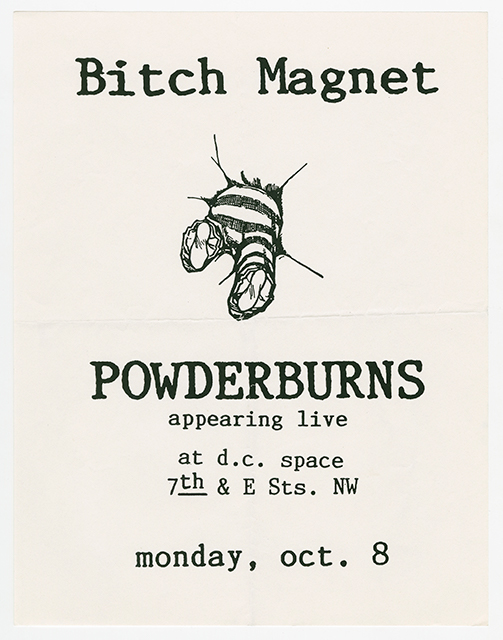

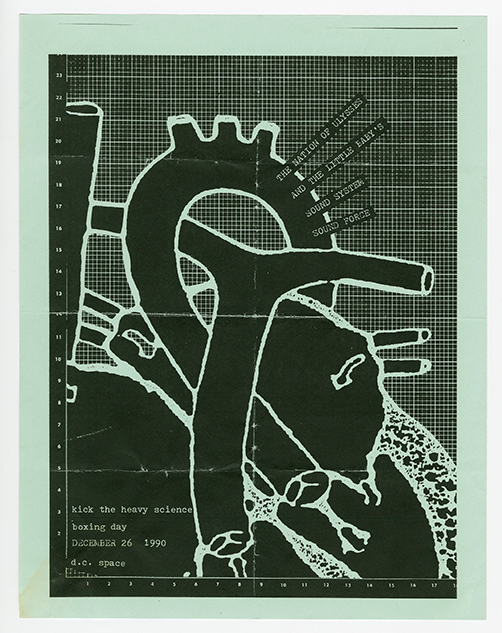

Slumberland, founded in 1989 by University of Maryland student Mike Schulman, released music in 1990 by Velocity Girl, Powderburns, and Big Jesus Trash Can, who soon changed their name to Whorl. Slumberland would only remain based in the D.C. area for a few more years before moving to California, but the label was a critical part of establishing D.C.’s punk-inspired noise-pop scene, which thrived throughout the decade.9 Velocity Girl and Whorl both appeared on the Pre-Moon Syndrome Post-Summer (Of Noise) Celebration Week! compilation album in 1990, assembled by photographer, concert booker, and author Cynthia Connolly. Tracks on the compilation—which also included Lungfish, Unrest, Holy Rollers, and Kim Kane’s post-Slickee Boys band Date Bait—were culled from a series of September 1989 concerts at dc space, where Connolly worked. She released the album on her label Sun Dog Propaganda, which also published Banned in D.C.: Photos and anecdotes from the D.C. punk underground (79-85), a book she co-authored in 1988 with Sharon Cheslow and Leslie Clague. The book was the first of its kind in documenting D.C. punk’s influential first wave of hardcore and emocore, serving as an accessible portal to the past for new waves of fans.

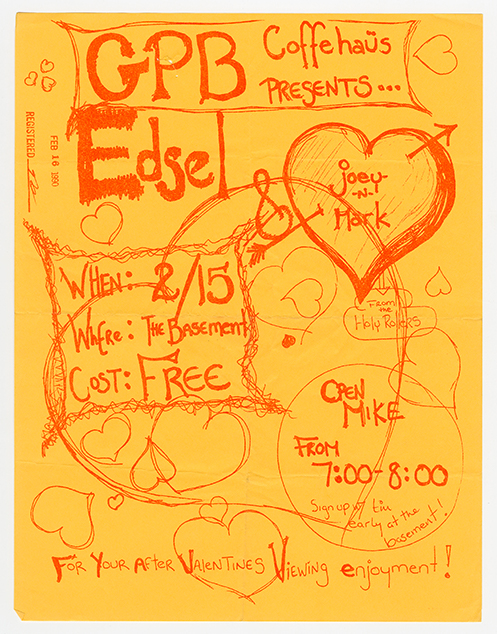

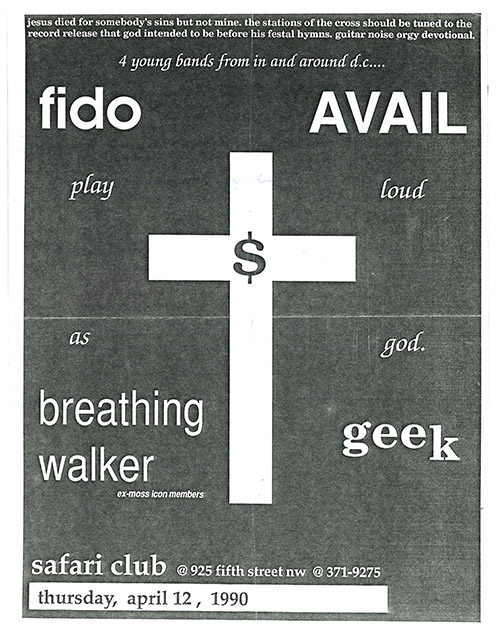

As indie rock and indie pop increasingly claimed space in the scene, another new label with broad ambitions was launched in 1990, and would push D.C. punk into new realms of creativity, connection, and DIY inspiration. Simple Machines was formed by Jenny Toomey of the bands Geek and Choke and Nomadic Underground fanzine editor Brad Sigal, both of whom resided in the Positive Force group house. Sigal soon moved on and Toomey was joined by Kristin Thomson. The duo would notably influence D.C. music and indie rock, in general, almost immediately. Simple Machines released the 7-inch compilation EPs, Wedge and Wheel, which featured Holy Rollers, Lungfish, Edsel, Geek, and the Hated, showcasing the kind of stylistic heterogeneity that necessitated these growing labels. Simple Machines gained attention for its themed releases, creative packaging, activism, and dedication to community connection. The label felt like a continuation of what Dischord and other labels had done in the 1980s, but was clearly its own entity from the beginning. “We had a sense of humor,” Toomey recalled. “There was a lot of self-effacing humor that was not necessarily part of the D.C. scene, which was more earnest. So I think there was sort of a marriage between the aesthetics—making everything pristine, the politics—but also trying to have a sense of humor, and to be funny and self-effacing.”10

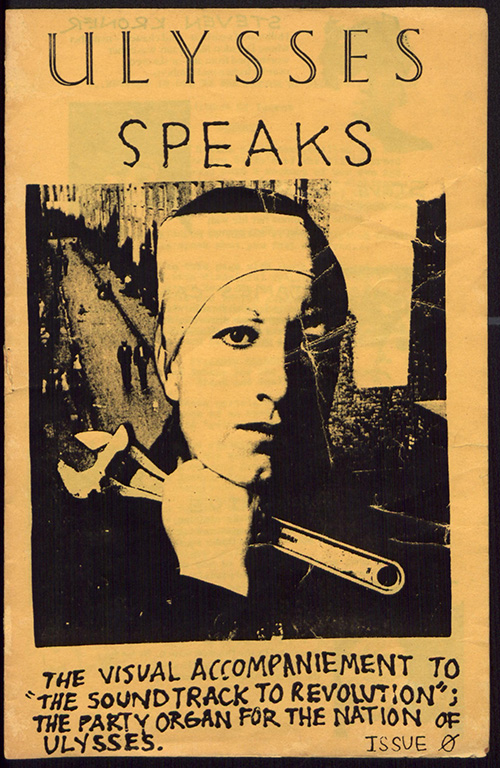

The D.C. scene continued expanding its influence and fostering links with other scenes. The most notable union was first symbolized through the joint release of Nation of Ulysses' first EP on both Dischord and K Records, an indie label from Olympia, Washington. The three-song, self-titled EP captured the group’s blend of bellicose post-hardcore, elements of free jazz, and radical politics. The EP was the foundation for their self-described “Soundtrack to Revolution,” 13 Point Program to Destroy America, an album that Dischord released the next year. The Olympia-D.C. connection would particularly bloom in the year ahead with the birth of the feminist punk movement, Riot Grrrl.

Pieces were now in motion for an explosion in national awareness of the D.C. punk and indie scene, which would rival the early heyday of hardcore. New bands, new participants, and a new movement would all soon come to represent the city and help redefine punk while holding true to the core ethos that had guided the scene for the last decade.

Further Listening

Bad Brains/Black Market Baby. Y&T Records, Split 7-inch single. (Recorded in 1980-81)

Black Market Baby. Drunk and Disorderly. Y&T Records, 7-inch single. (Recorded in 1986)

Choke. Kingdom of Mattresses. Simple Machines/Vermin Scum, 7-inch EP.

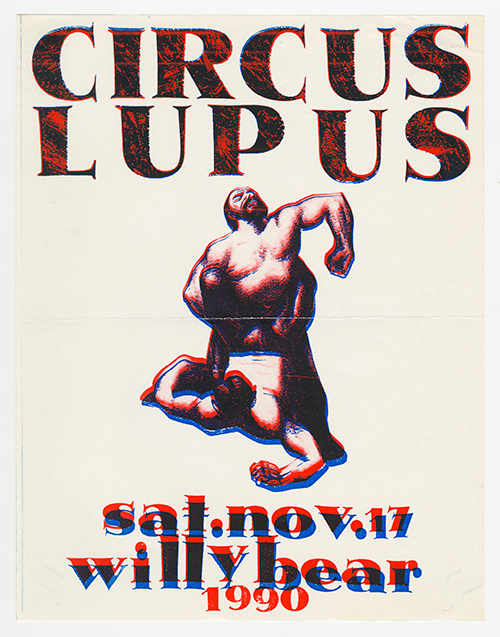

Circus Lupus. "Tightrope Walker"/"Chinese Nitro." Cubist Productions, 7-inch single.

Far Cry. Story of Life Crucial Response, 7-inch EP.

Fidelity Jones. Venus on Lovely. Dischord Records, Single.

Fugazi. Repeater. Dischord Records, LP.

Holy Rollers. As Is. Dischord Records, LP.

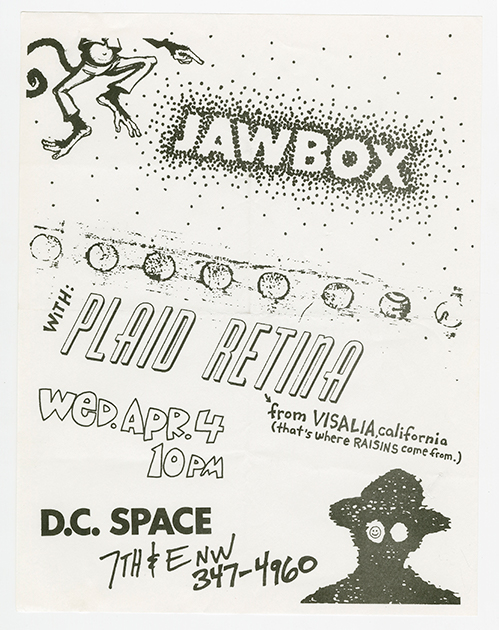

Jawbox. Jawbox. Dischord Records/DeSoto Records, 7-inch EP.

Manifesto. Burn. Y&T Records, 7-inch single.

Manifesto. History. Fire Records, 12-inch single.

Rain. La Vache Qui Rit. Peterbilt Records, 12-inch EP.

Senator Flux. The Criminal Special. Emergo Records, Album.

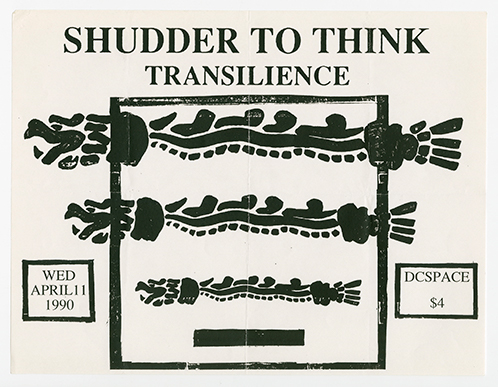

Shudder to Think. Ten Spot. Dischord Records, Album.

Shudder to Think/Unrest. Catch of the Day. Big Dragg Records, Split 7-inch single.

Various. The Pre-Moon Syndrome Post-Summer (Of Noise) Celebration Week!, Sun Dog Propaganda, Compilation album.

Various. Wedge. Simple Machines, Compilation 7-inch EP.

Various. Wheel. Simple Machines, Compilation 7-inch EP.

Velocity Girl. “I Don’t Care If You Go/Always,” Slumberland Records, 7-inch single.

Materials are drawn from the Chris Baronner digital collection on D.C. Punk, the Paul Bushmiller collection on punk, the Sharon Cheslow punk flyers collection, and the Ian MacKaye digital collection of punk fanzines.

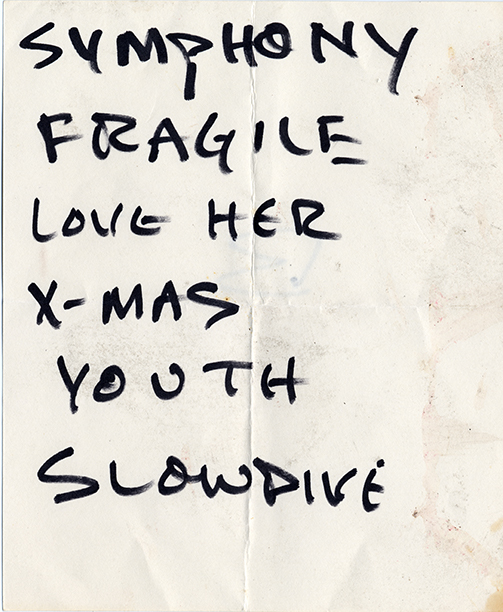

Tap or hover over an image to learn more.

FLIERS

ZINES

EPHEMERA