As in the rest of the world, the 1980s did not end quietly in Washington, D.C. 1989 was the beginning of the George H.W. Bush presidency, a four year term of profound global consequence. The fall of the Berlin Wall in Germany on November 9th was depicted as a synecdochic culmination of years of growing unrest within the Soviet Bloc. In the final weeks of 1989, the United States again became embroiled in military conflict in Central America. On December 20th, the Bush administration, with bipartisan support, began the invasion of Panama to overthrow the government of Manuel Noriega, a move which was decried internationally.1

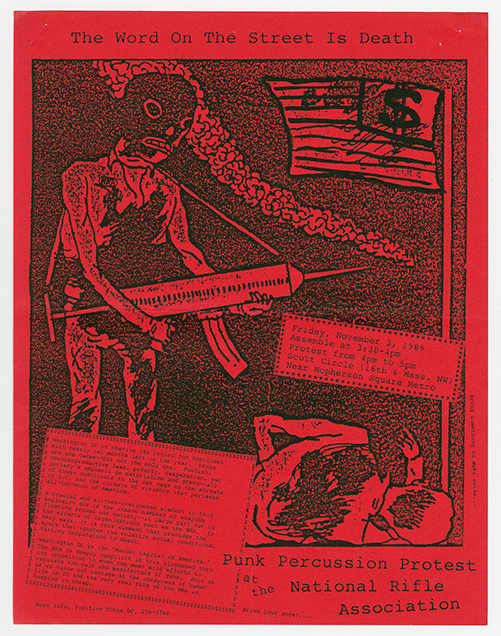

Drugs, especially crack cocaine, were inescapable in the District, dominating local and national news. By December, drug-related articles ran on the front page of The Washington Post 26 out of the month’s 31 days.2 Bush attempted to, as many had before him, make an example out of the local community of Washington, D.C. The president re-ignited the previous administration's anti-drug fervor when he made a televised speech from the Oval Office holding up a bag of crack cocaine that was purchased in Lafayette Park, across from the White House, saying: "it’s as innocent looking as candy, but it’s turning our cities into battle zones."3 However, as with the previous administration's war on drugs, the paternalistic language belied predatory behavior. The Washington Post soon reported on how the DEA struggled to find anyone willing to sell cocaine that close to the White House and eventually lured a D.C. high school senior into the sting operation. Despite being used as a political prop, that student was convicted on earlier sales and sentenced to ten years in prison as a result of the operation. The community of Washington continued to be both a stage and a lived space where national politicians attempted to foist their vision and make an example of the city without much attention to the people actually living there.

...

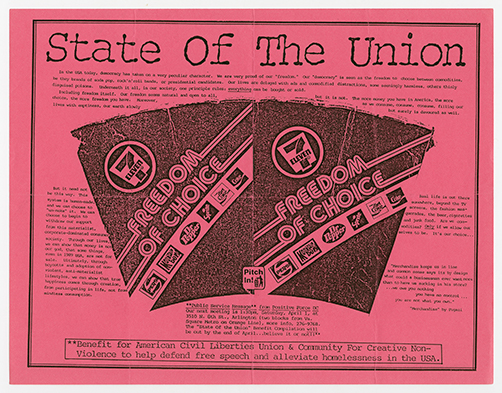

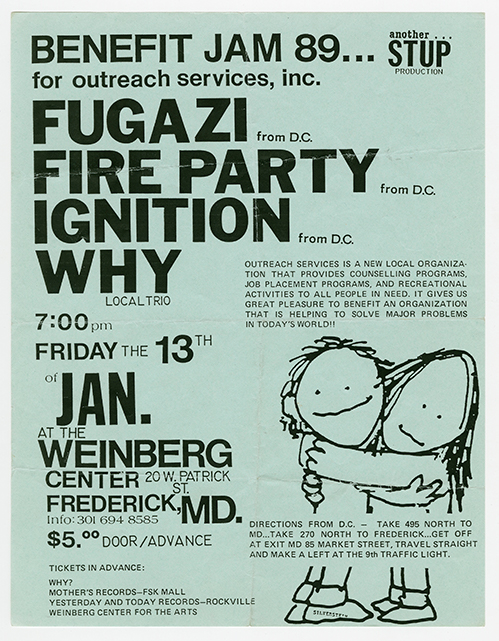

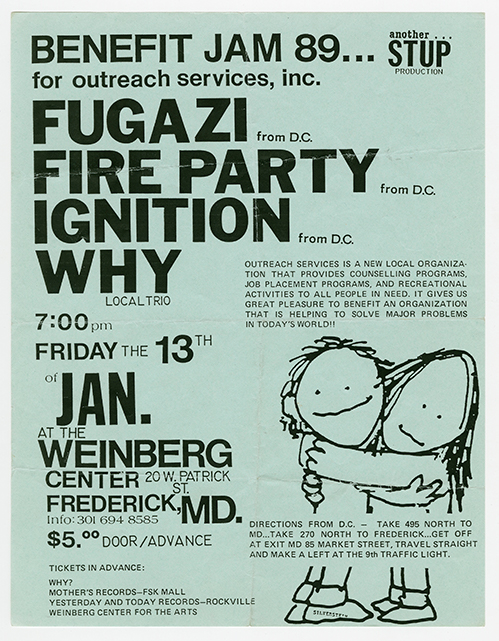

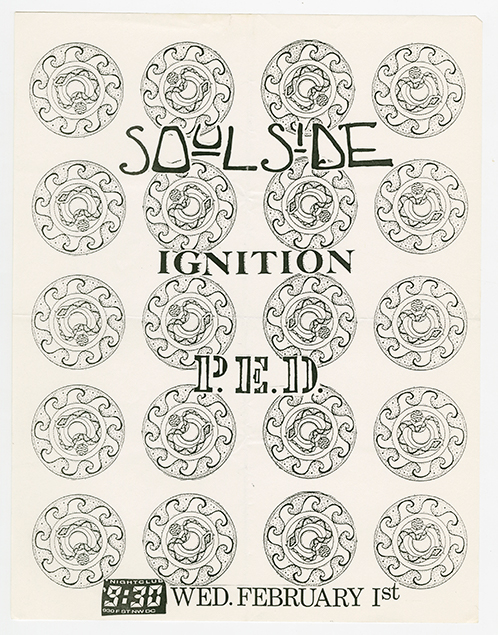

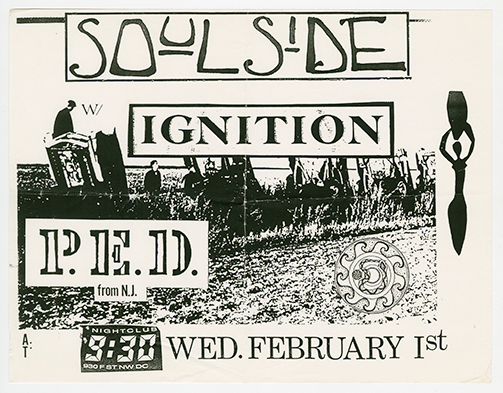

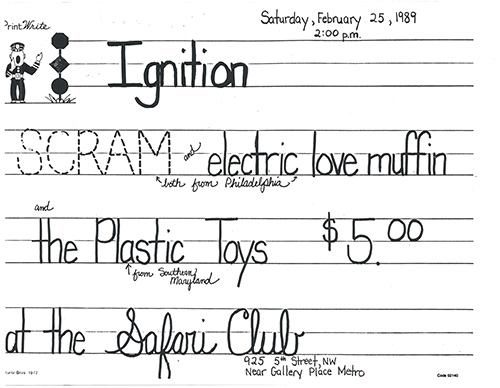

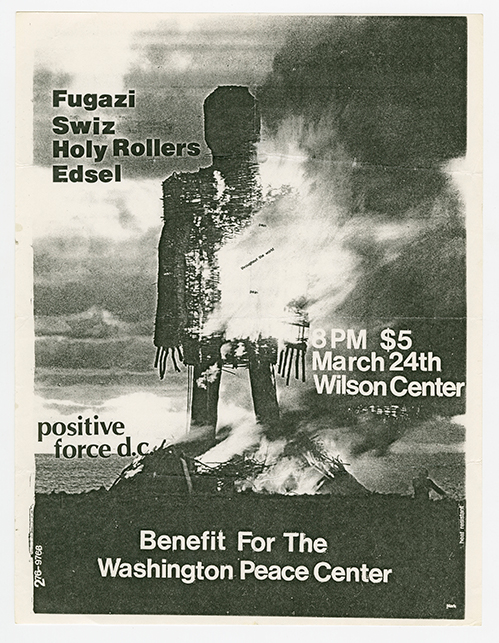

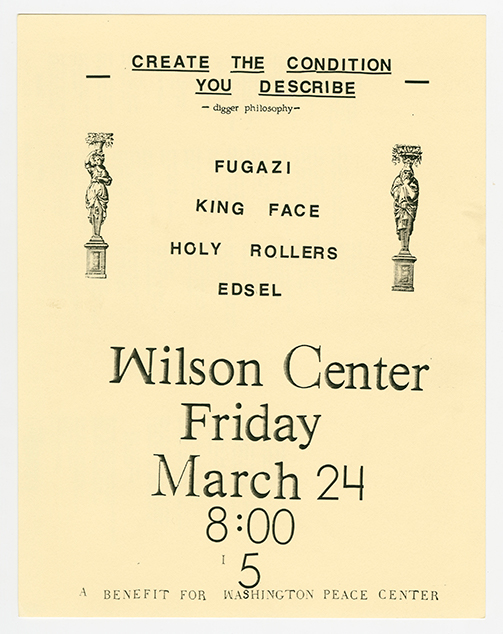

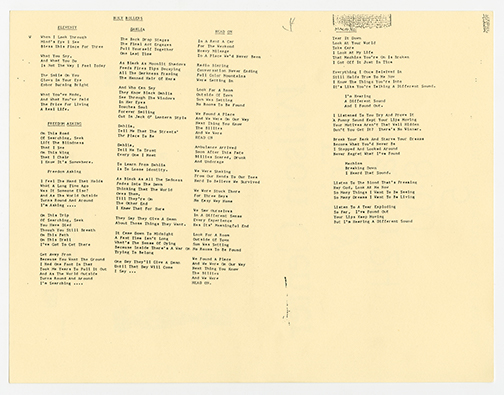

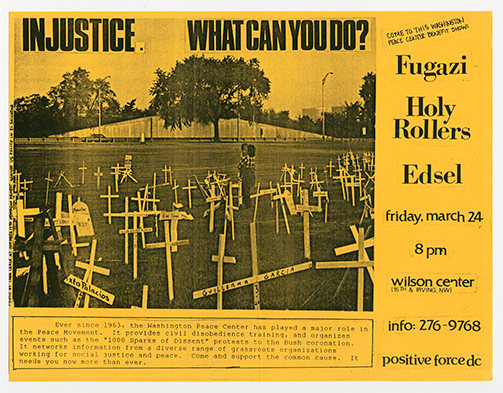

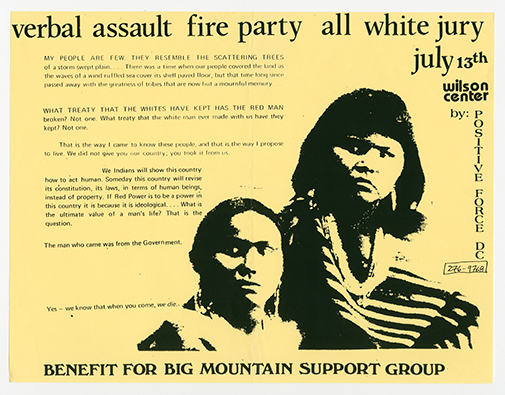

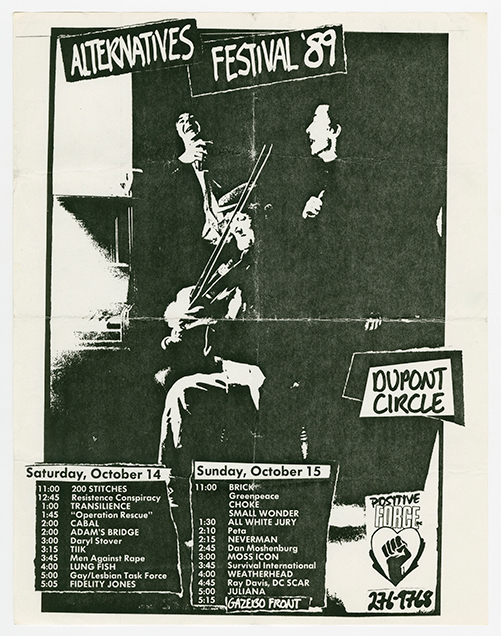

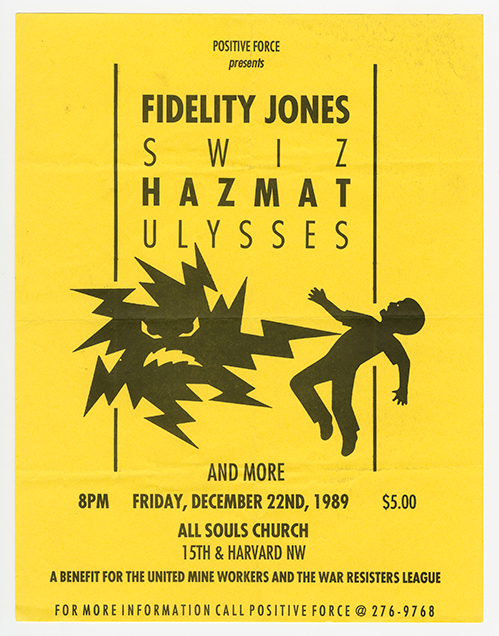

The D.C. punk scene was evolving in its music and its activism over the course of 1989. In April, Dischord released the benefit compilation State of the Union, which was compiled by Mark Andersen of Positive Force. Featuring music by Soulside, Scream, Ignition, Fugazi, Marginal Man, King Face, Three, Christ on a Crutch, Broken Siren, and One Last Wish, the compilation spoke to the stylistic breadth of what had grown from the more narrowly-defined punk of earlier years. Included with the record was a twelve-page booklet outlining Positive Force's stances both locally and internationally, decrying American militarism and global apartheid while also laying out a proposed boycott list.4

Much like Flex Your Head seven years before it, State of the Union captured for many what they felt had been developing in the scene for years. As Patrick Foster wrote in his review of the album in Sweet Portable You:

Contained within this record is a thick and searing aggregation of statements that teem with anger and emotional bitterness, drawn directly from the strain of living the District of Columbia’s daily hardening-of-the-arteries barrage of murder and moralistic neglect. It’s anger captured and collated, anger turned in the right direction, not blown through a revolver or funneled backwards into the bloodstream, but held over your head as evidence, involked (sic) to suggest and alter. And as such, it deserves not only your open-minded and sober consideration, but your complete and undivided attention.5

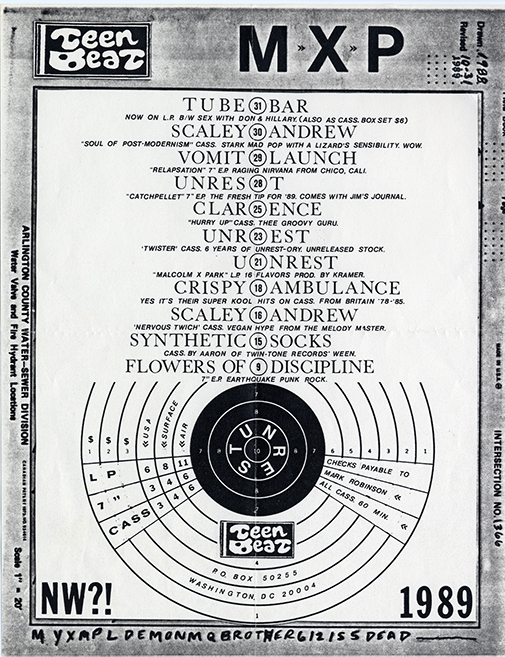

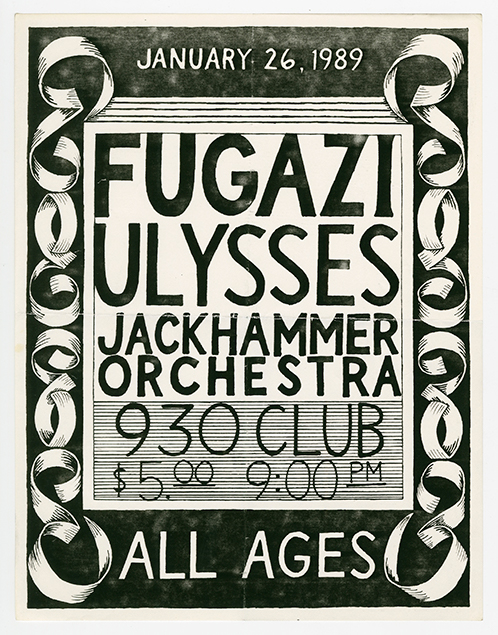

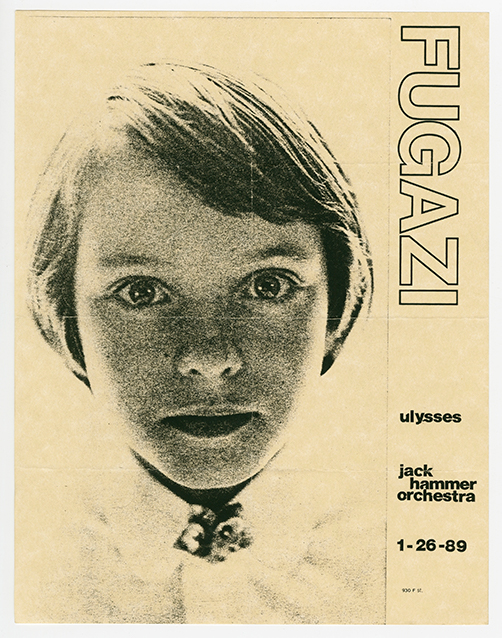

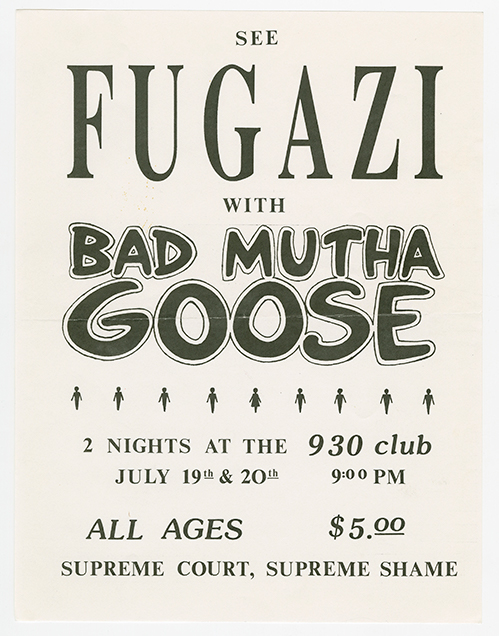

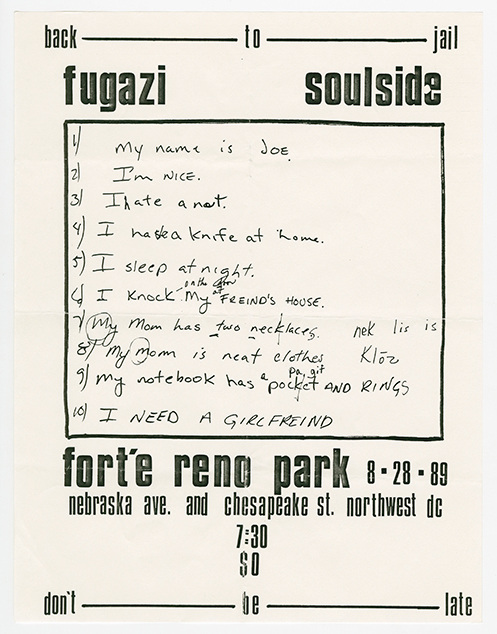

Fugazi built off the attention their debut EP in 1988 had derived, touring extensively in 1989. The group released the Margin Walker EP in June and then, subsequently, 13 Songs, which compiled the first two EPs onto a compact disc. The group also released a new, three-song EP—”Song #1,” “Joe #1,” and “Break-In”—as part of the “Single of the Month Club” created by Sub Pop Records, a record label from Seattle, Washington that had its roots in the punk fanzine community of the early 1980s. Fugazi agreed to release the 7-inch EP initially through Sub Pop with the understanding that Dischord would release its own edition of the record, 3 Songs, the following year. Sub Pop then marketed the limited edition single as fodder for collectors, a move that rankled Fugazi’s populist instincts. “People shouldn’t buy that shit,” guitarist/vocalist Guy Picciotto remarked. “I don’t want people to feel like they have to join that club to get the music,” guitarist/vocalist Ian MacKaye explained, noting that the songs would soon be available on Dischord. “People who have to have that sleeve or have to be part of the elite who have that, well, then that’s their thing. But people have the alternative and that’s what we offer them.”6

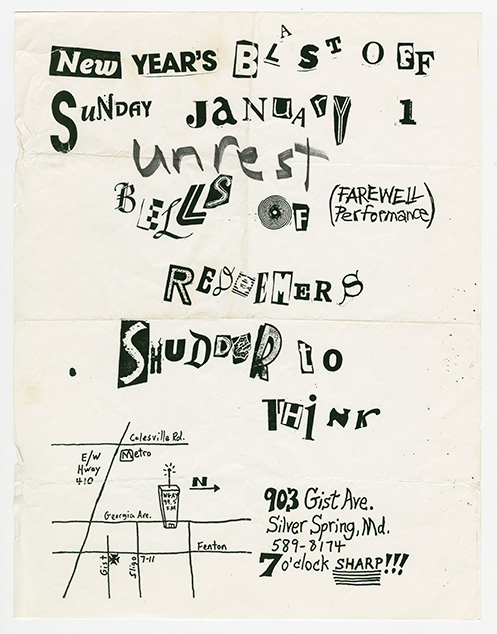

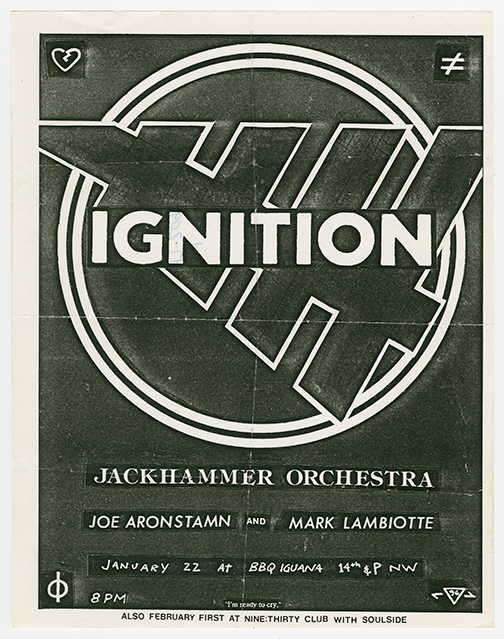

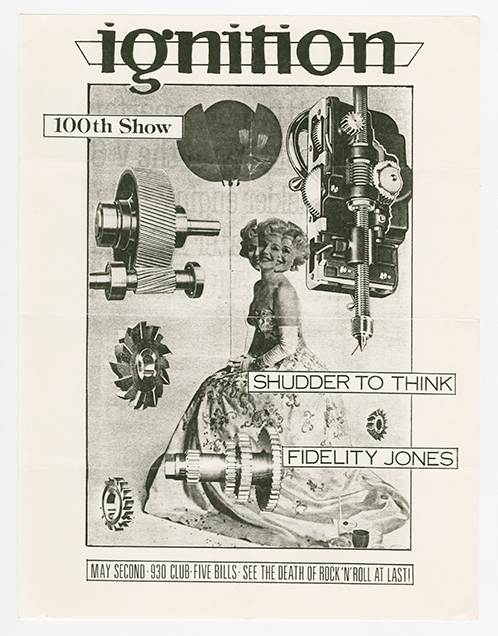

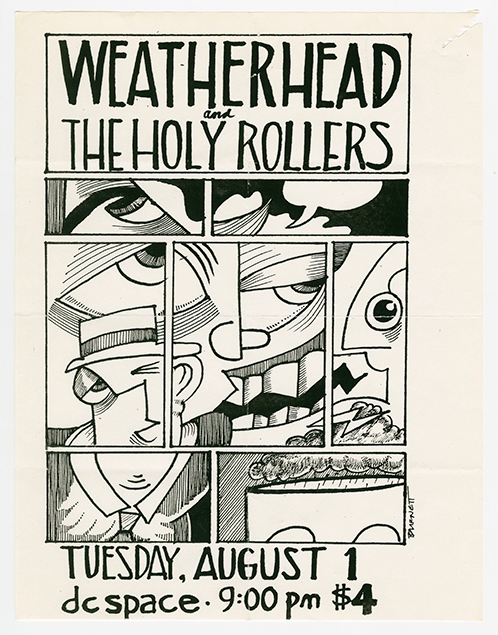

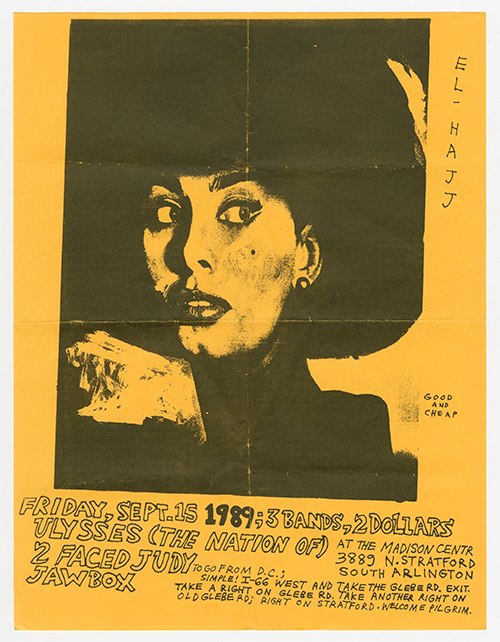

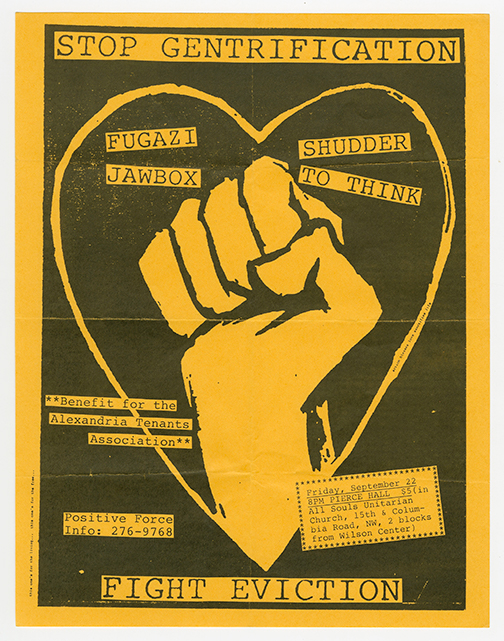

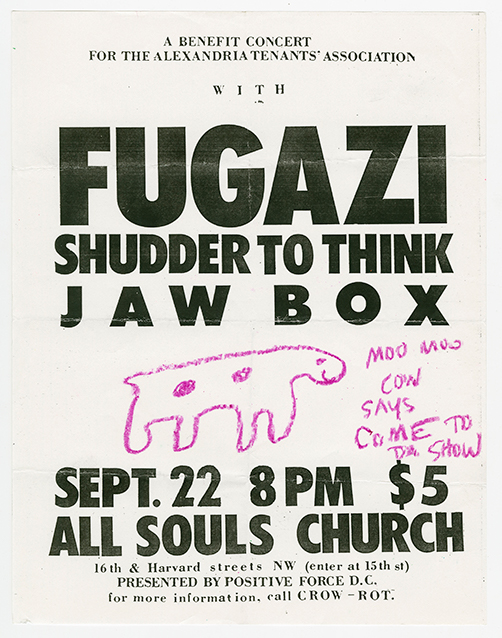

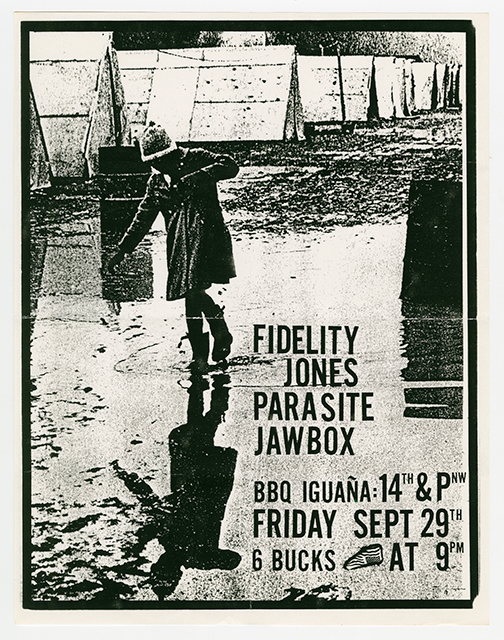

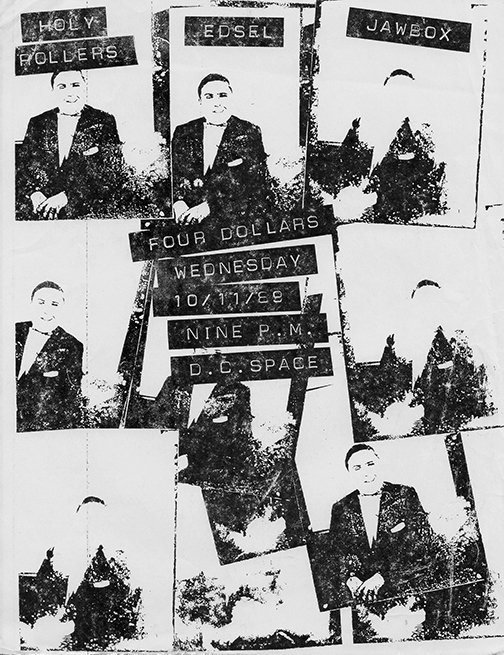

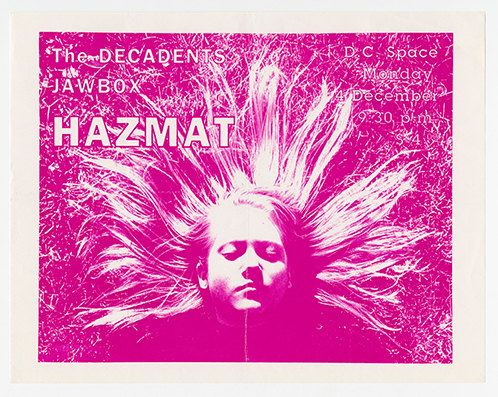

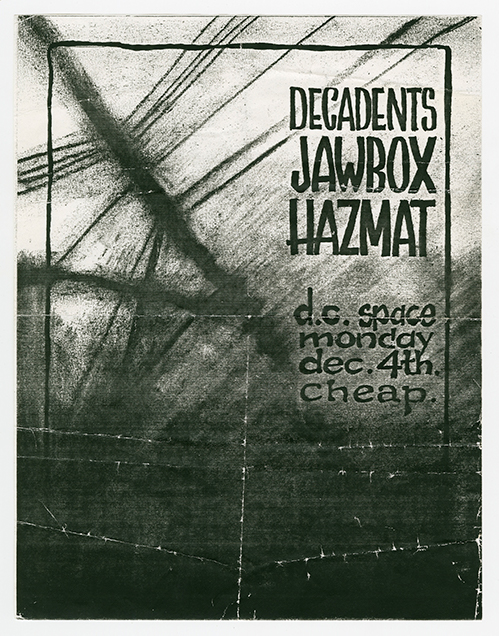

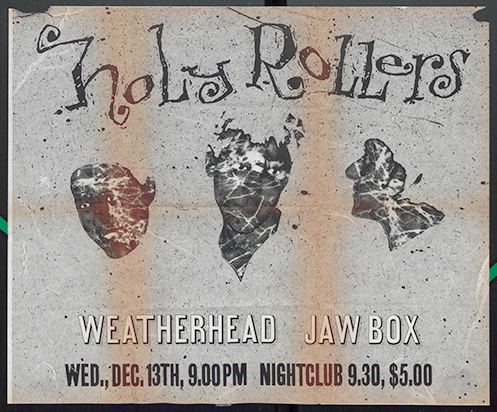

While the issue-driven content of local artists remained as direct as ever, the sound of the community continued to change, as did its participants. Recent mainstays King Face, Ignition, and Soulside all broke up in 1989.7 In addition, one of the last remaining groups from the initial wave of hardcore in the early 1980s, Government Issue, also disbanded, with vocalist John Stabb moving on to a short-lived new project, Weatherhead.8 G.I.’s dissolution also served as the point of genesis for another band, but this one would reverberate for decades to come. Jawbox was formed in 1989 by former G.I. bassist (now on guitar and vocals) J. Robbins, bassist Kim Coletta, and drummer Adam Wade. Jawbox would soon be a primary player in dramatically reshaping the sound of D.C. punk.

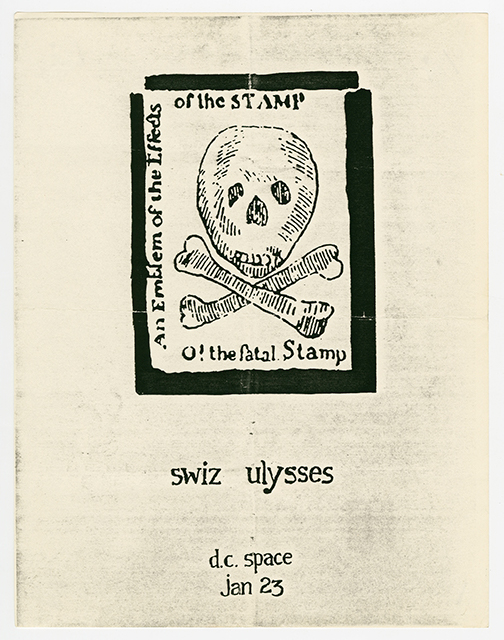

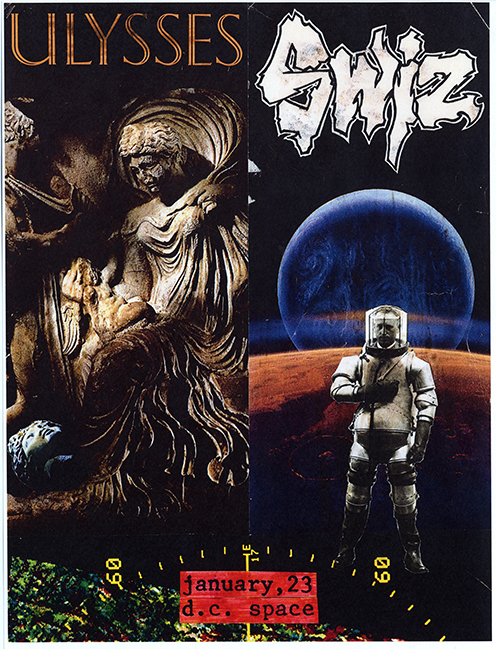

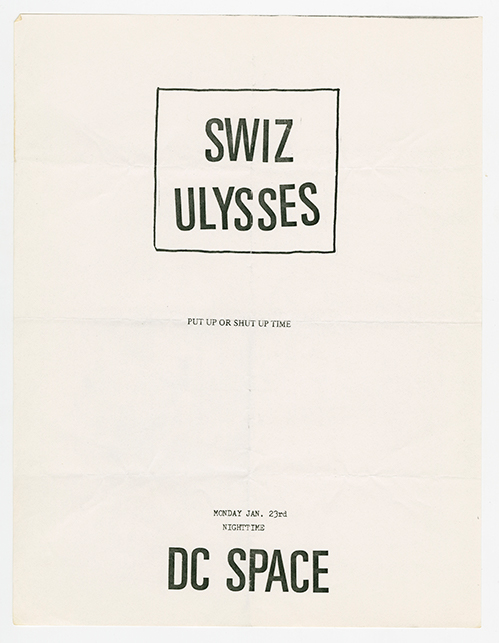

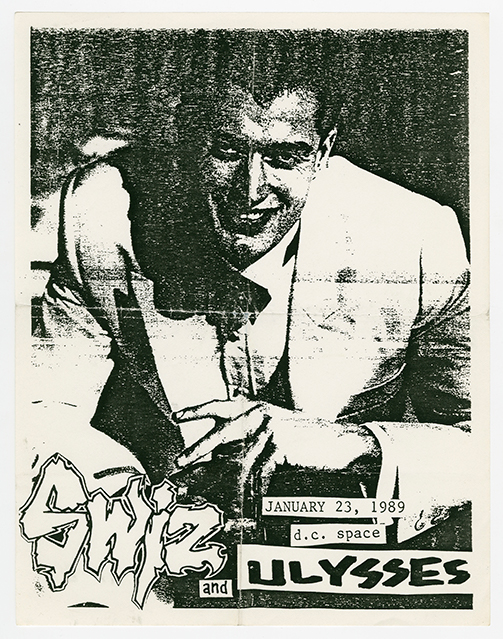

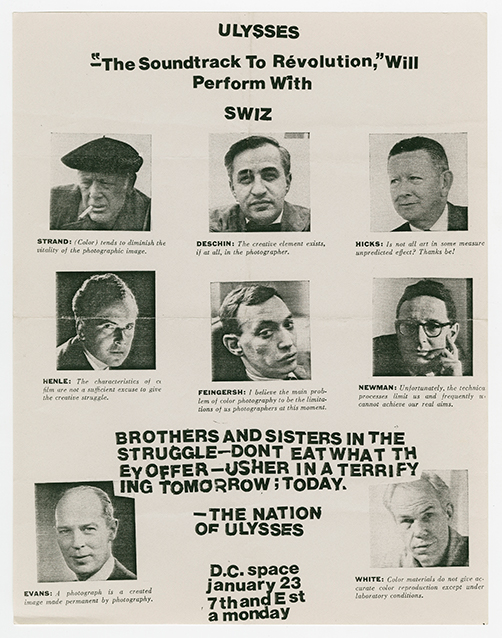

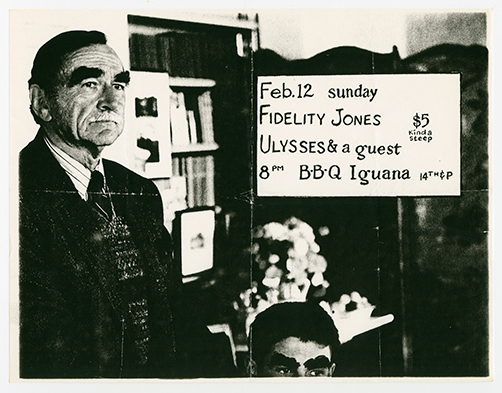

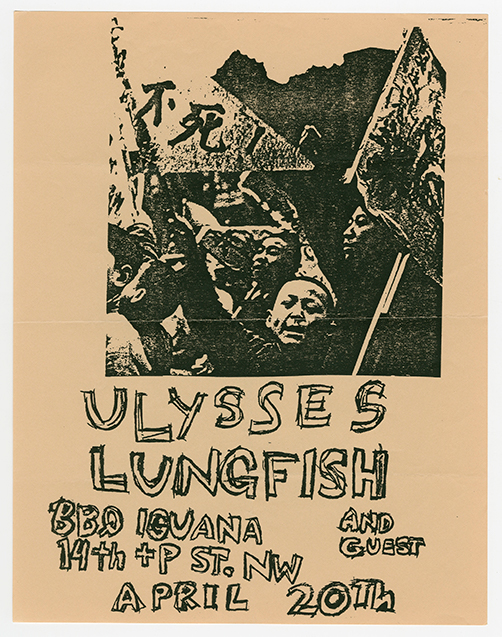

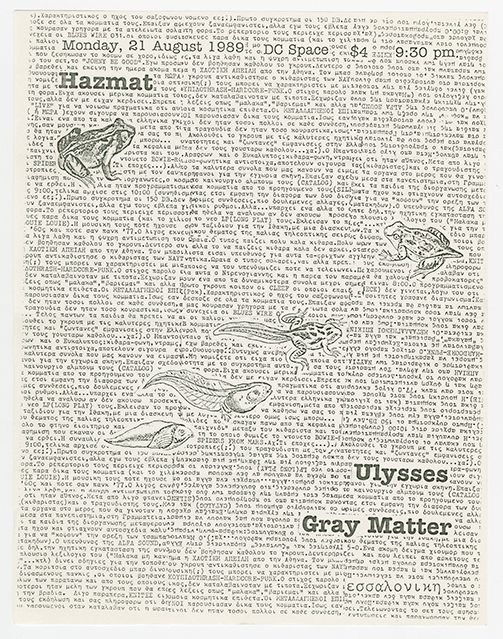

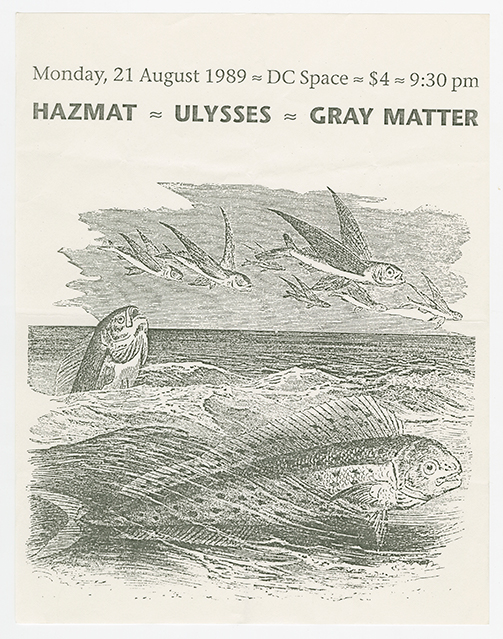

As ever, new bands cropped up to fill the void. James Canty, Steve Gamboa, Steve Kroner, and Ian Svenonius first played concerts in 1988 as Ulysses, but renamed themselves the Nation of Ulysses toward the end of 1989 with the addition of former Vile Cherubs guitarist Tim Green. The group was a unique presence locally, their manic performances and radical politics moving them to the fore of the scene’s consciousness.9 They also published their own zine, Ulysses Speaks, packing frenetic, ersatz-revolutionary prose around images the band clipped and detourned to fit their “seriously unserious, reverently irreverent”10 identity. “Nobody really believed that the Nation of Ulysses were a terrorist group, but the Ulysses Speaks zines really created another mystery around the band,” musician and photographer Jeff Winterberg recalled. “This was the first zine I saw that was intentionally confusing. I wrote a letter asking for a t-shirt and they replied ‘We don’t sell t-shirts, only armaments.’”11

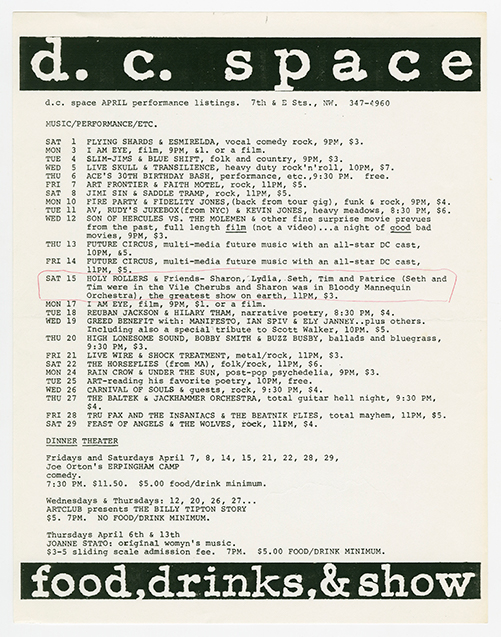

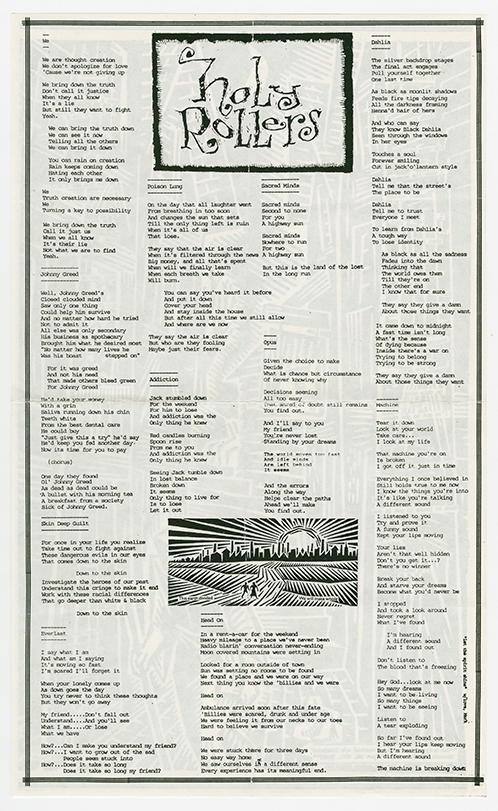

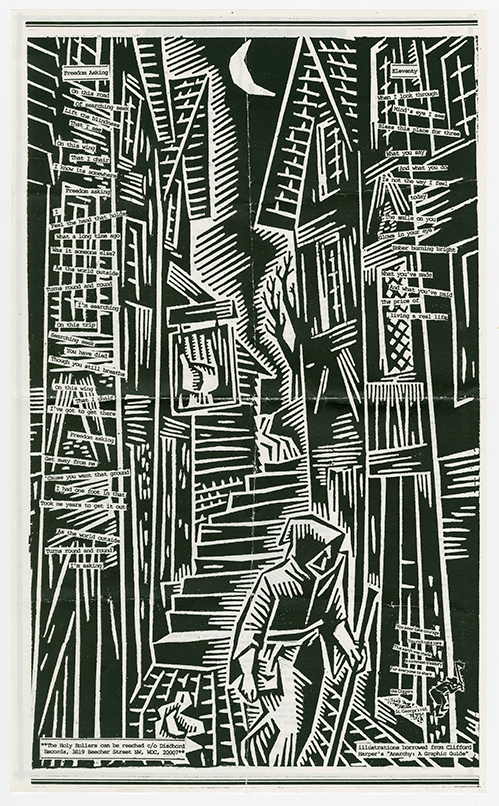

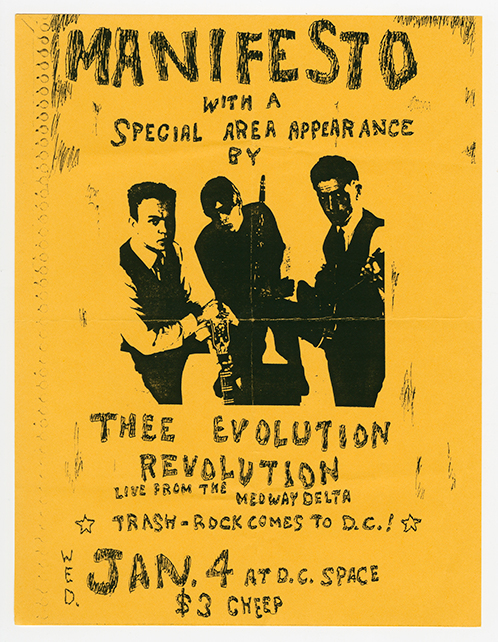

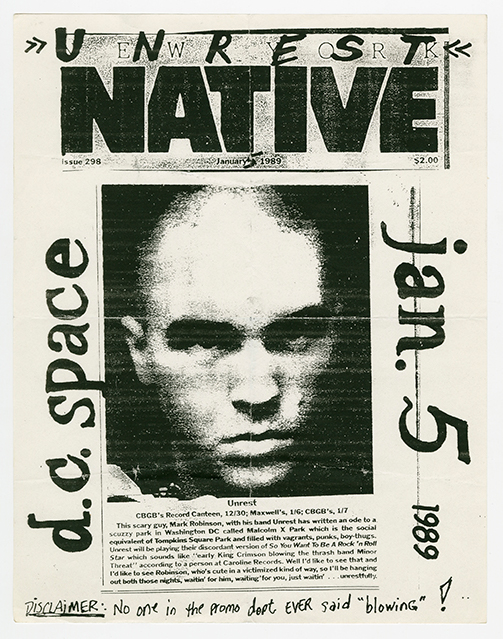

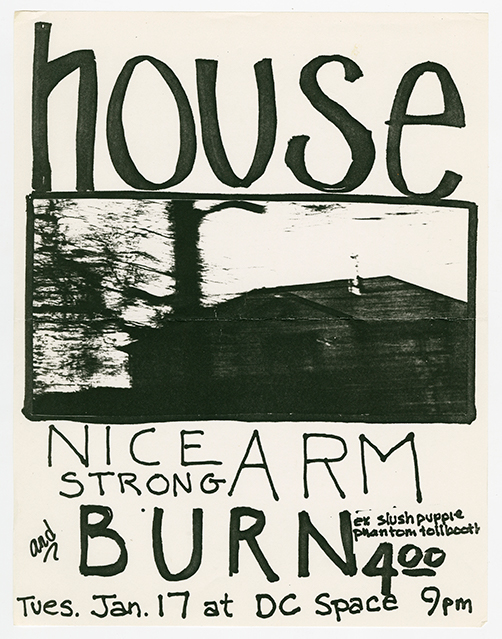

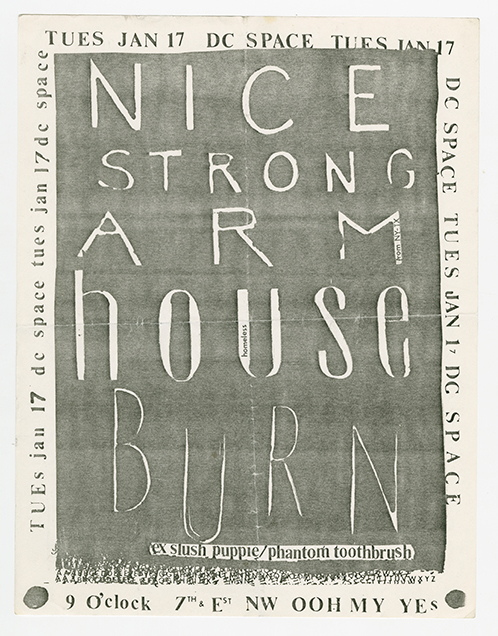

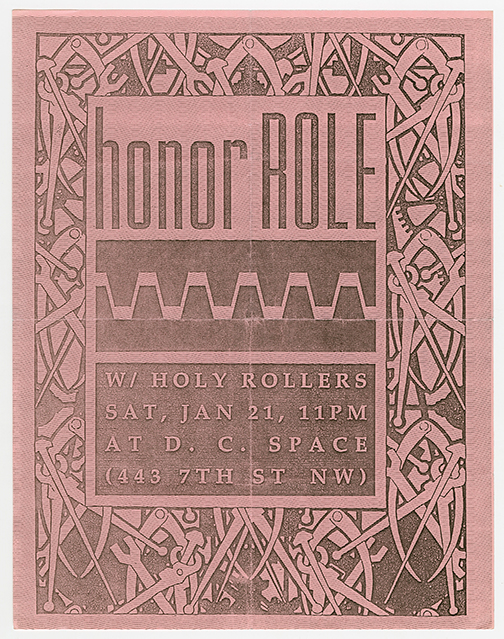

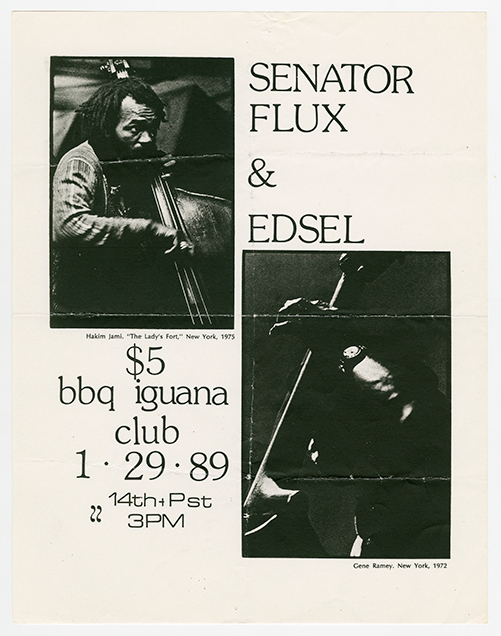

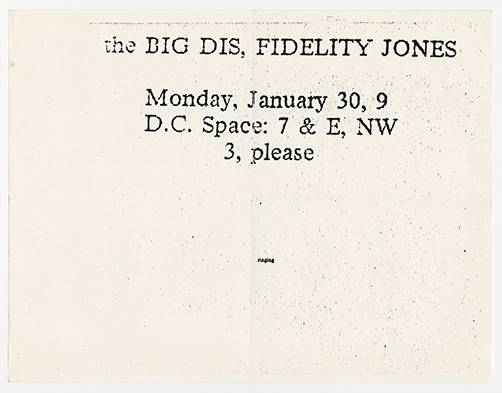

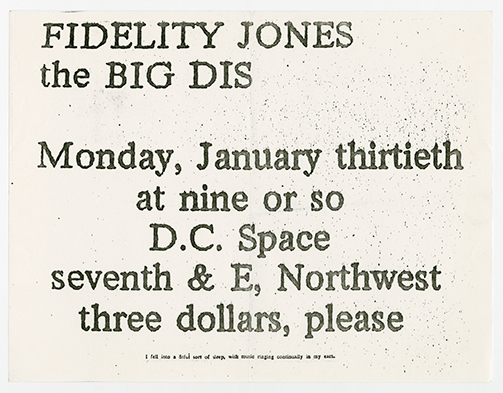

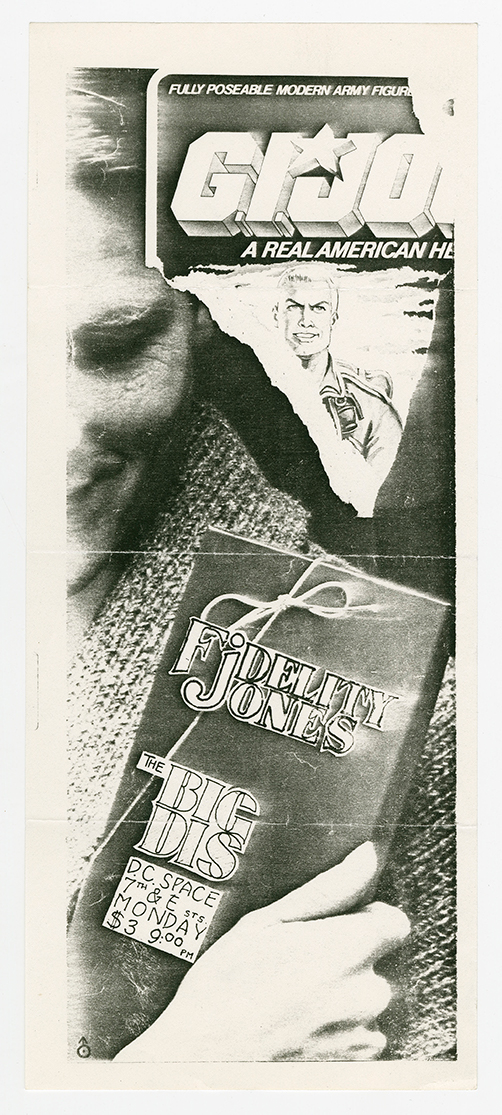

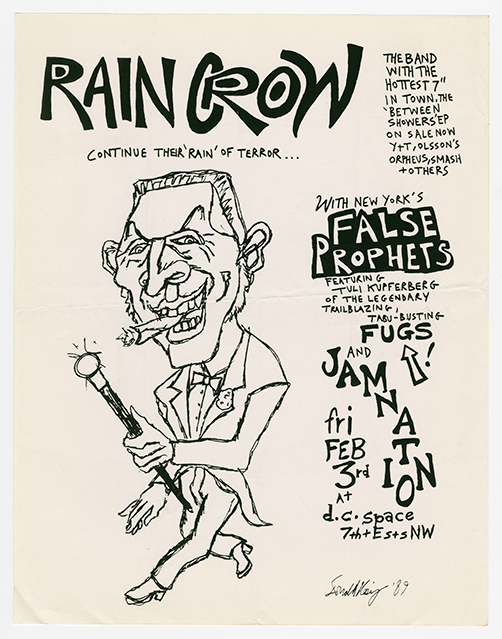

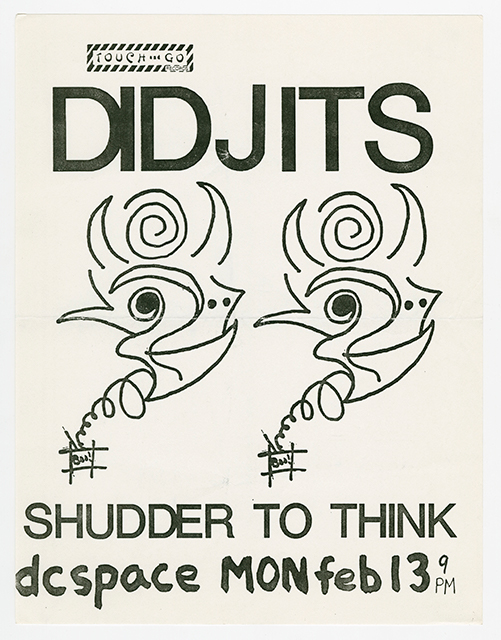

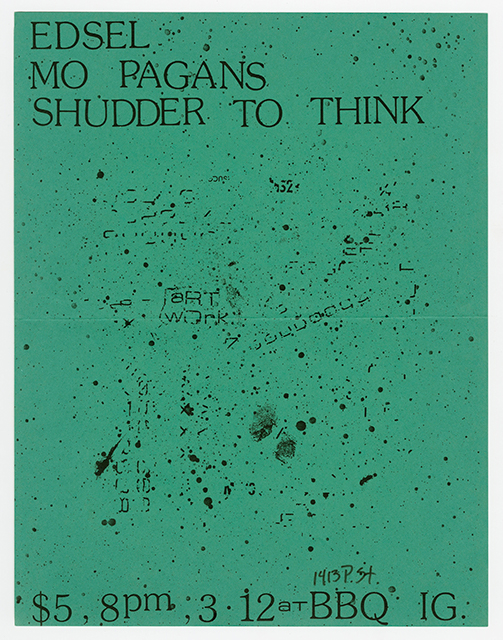

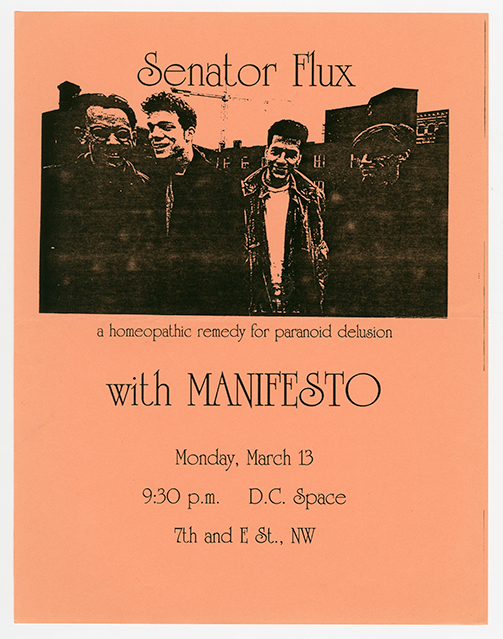

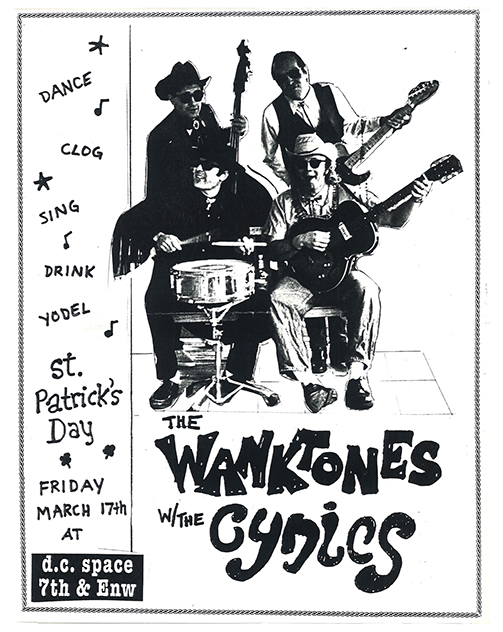

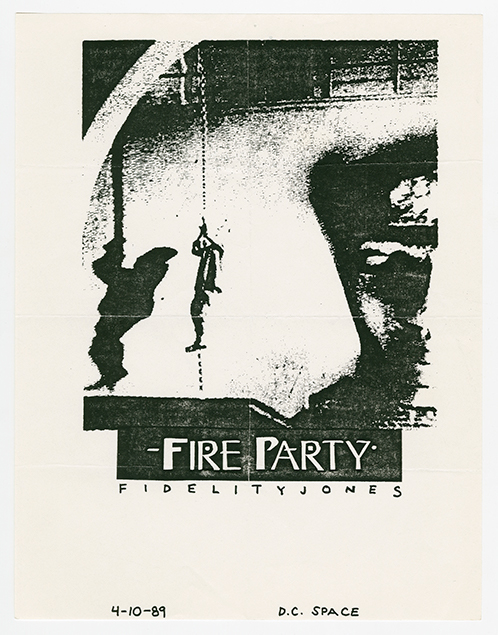

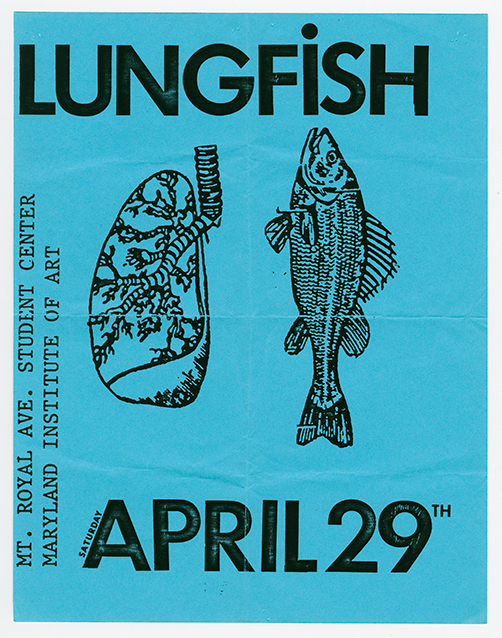

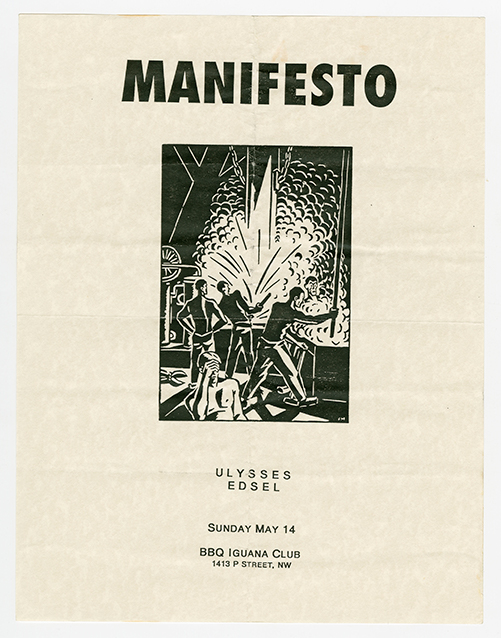

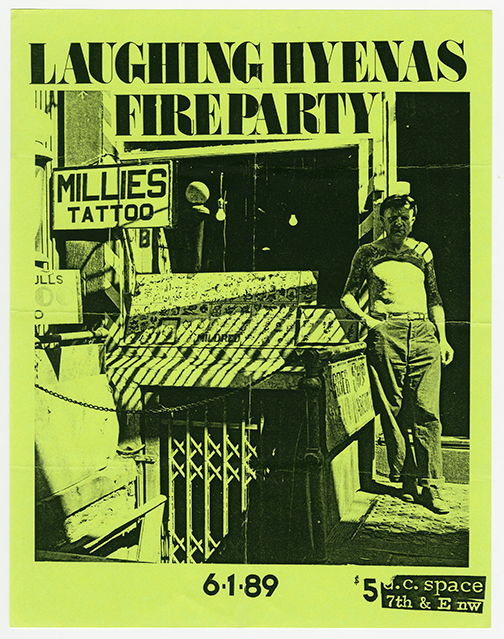

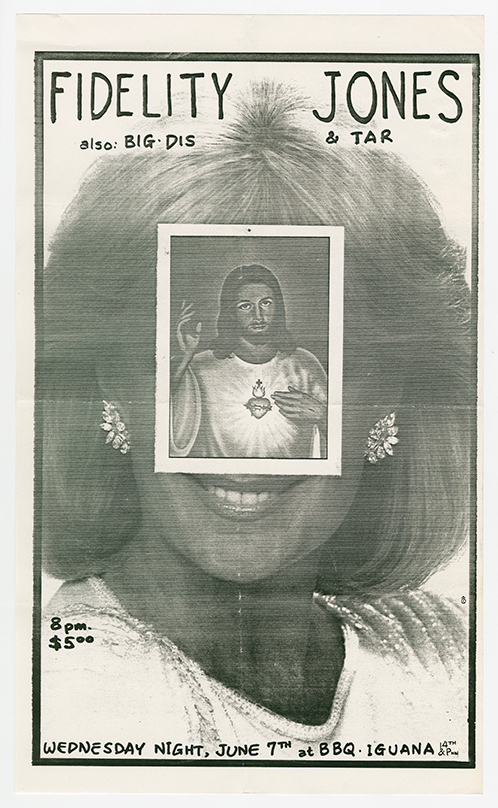

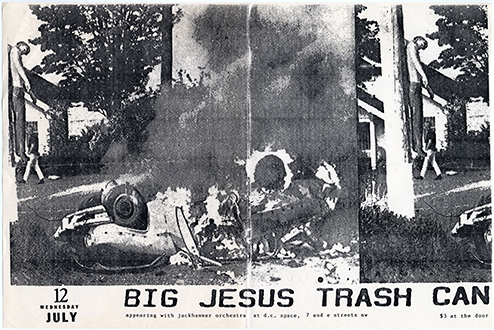

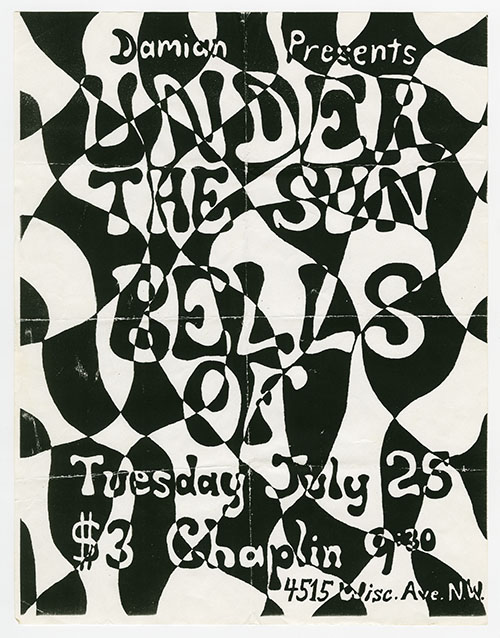

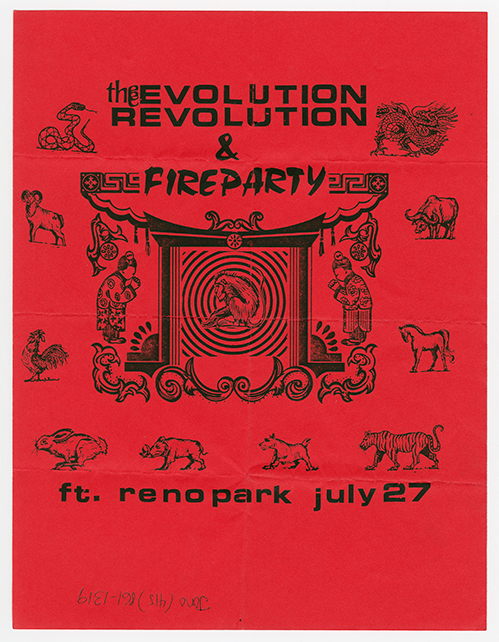

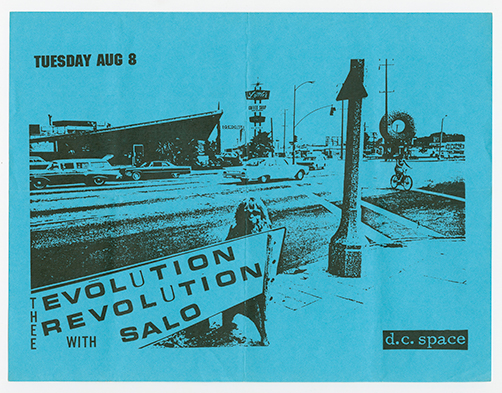

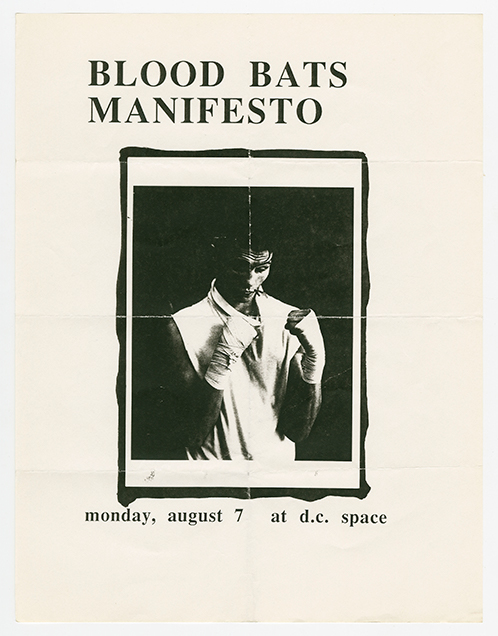

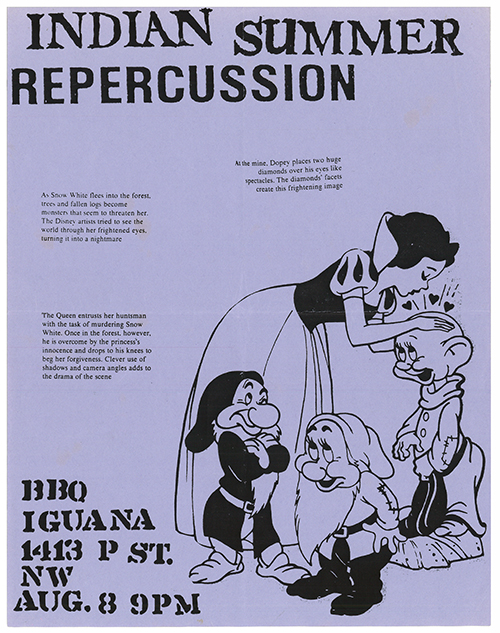

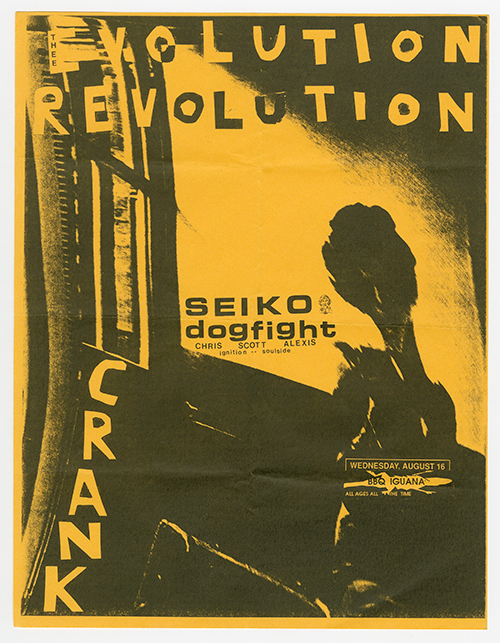

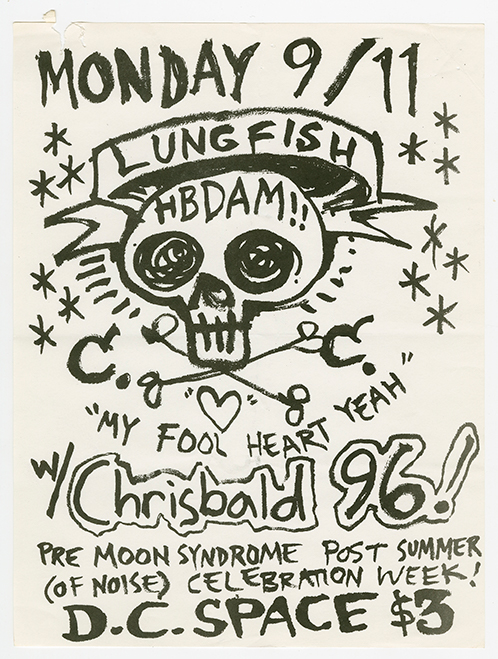

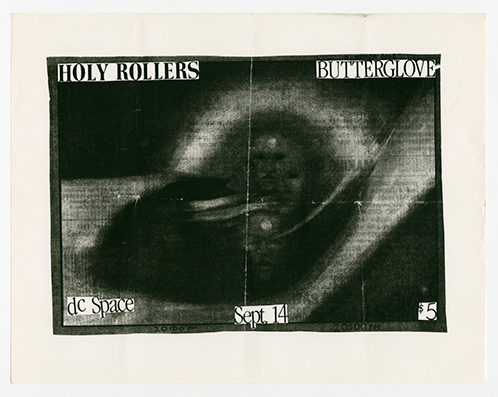

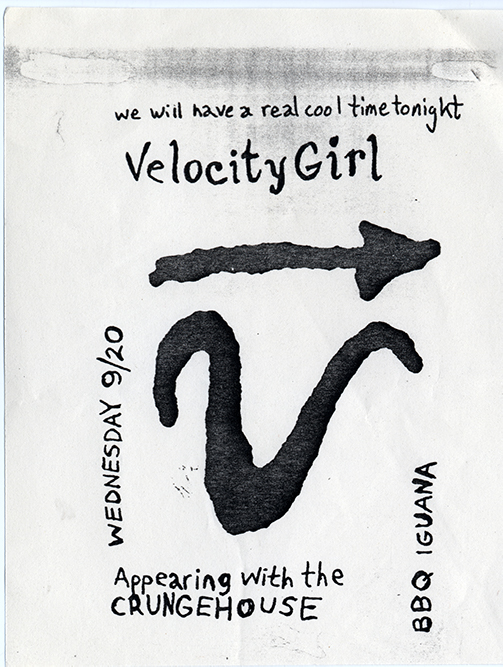

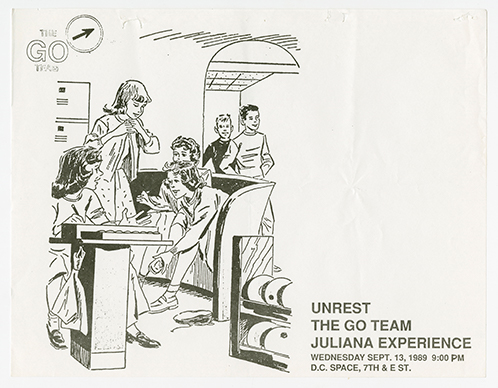

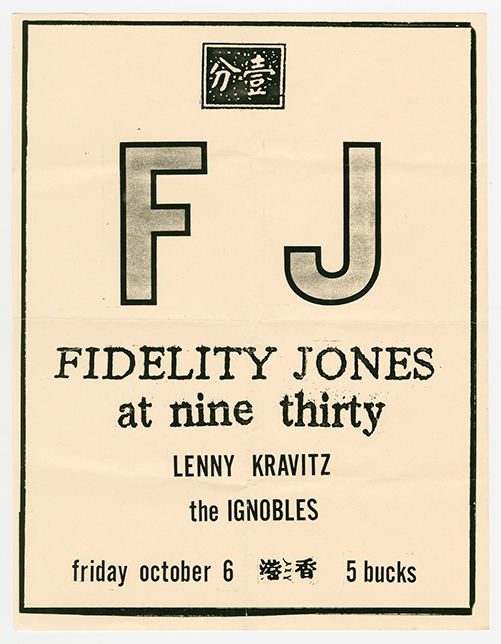

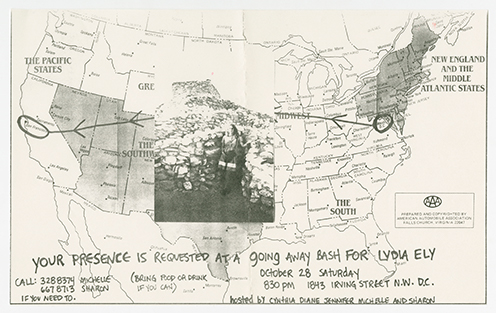

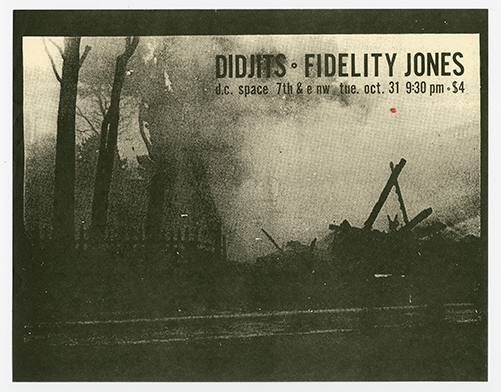

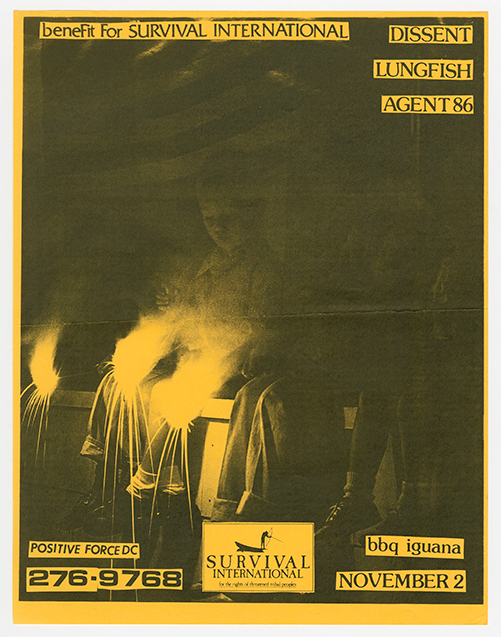

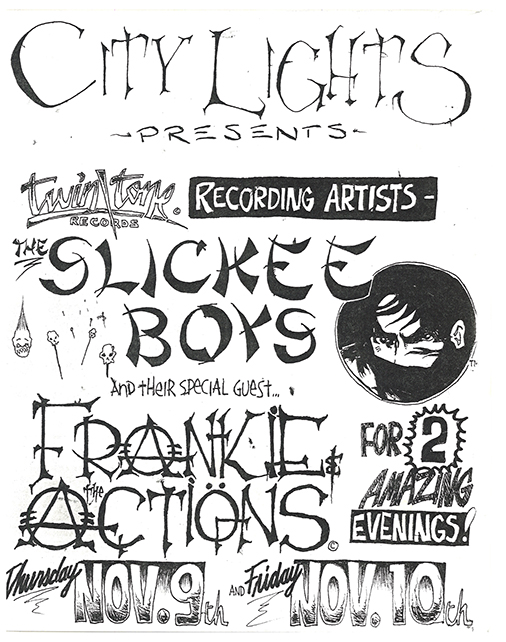

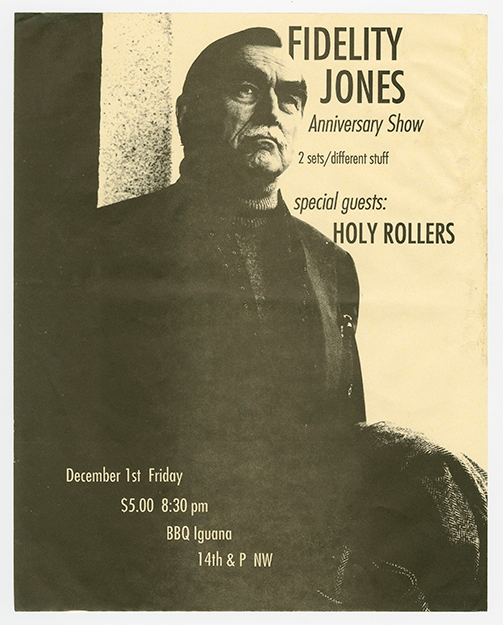

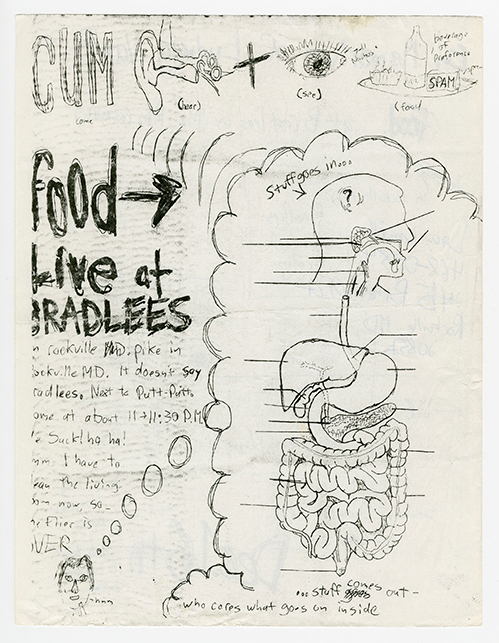

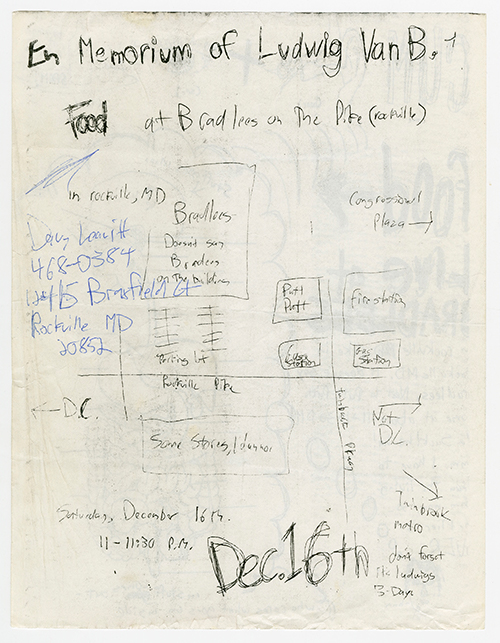

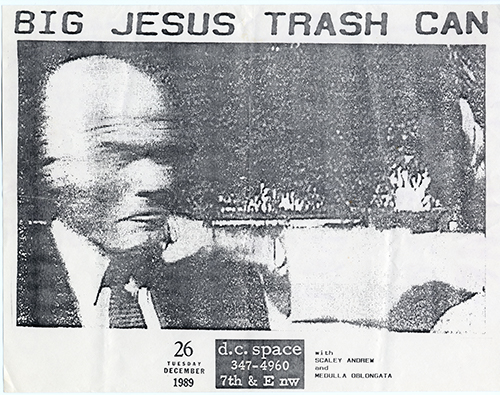

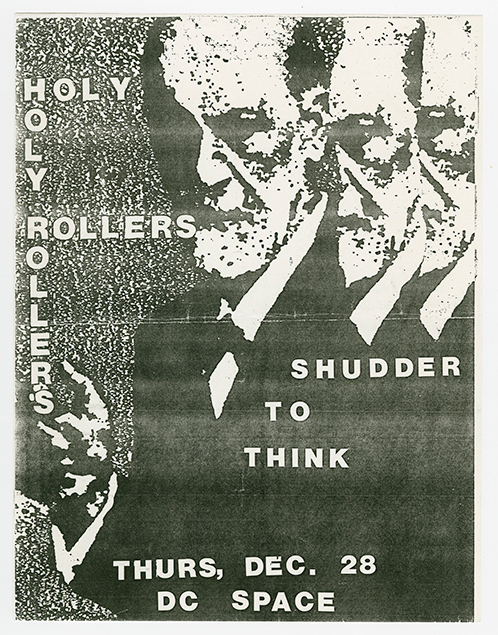

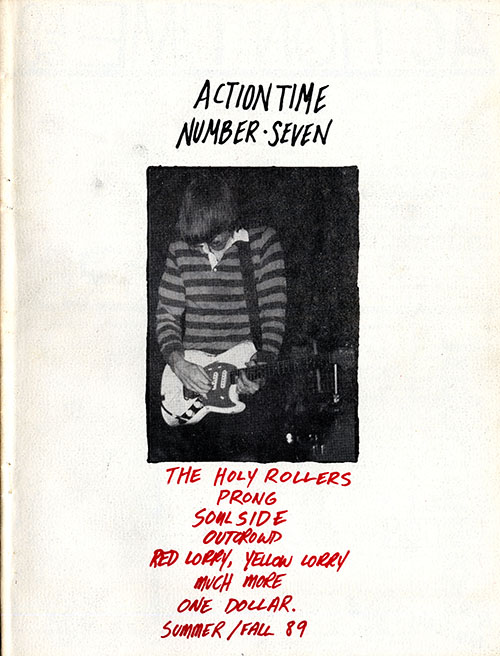

Other recently formed D.C. bands began to make an impression in 1989, as well, like Edsel, Holy Rollers, Fidelity Jones, Hazmat, Velocity Girl, Thee Evolution Revolution, and Manifesto, all of whom performed often throughout the year. The 9:30 Club and d.c. space continued to serve as reliable venues for local punk music in 1989, while the BBQ Iguana was a new space at 14th and P Streets NW that hosted dozens of punk shows this year.

True to the ephemeral nature of much of the city’s punk culture, BBQ Iguana had closed by the next year, with club owners Bill Stewart and Alice Despard (the latter of the band Hyaa!) citing crime and “routinely capricious” city inspectors as the motivators for a new location.12 The pair moved shop to Arlington, Virginia in 1990, opening Roratanga Rodeo, a bar that would soon evolve into Galaxy Hut.13 Under Despard’s oversight, following her split with Stewart, Galaxy Hut would develop into a hub of activity for the punk community in Arlington, which was the homebase for most of the D.C. punk’s scene’s most influential record labels, as well as the Positive Force group house, in the 1990s.

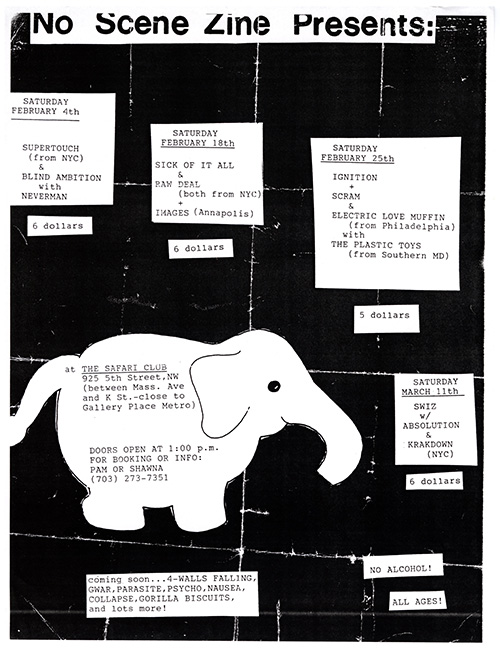

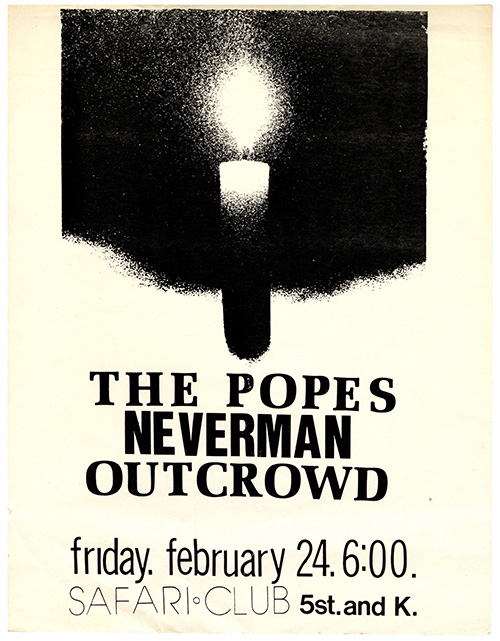

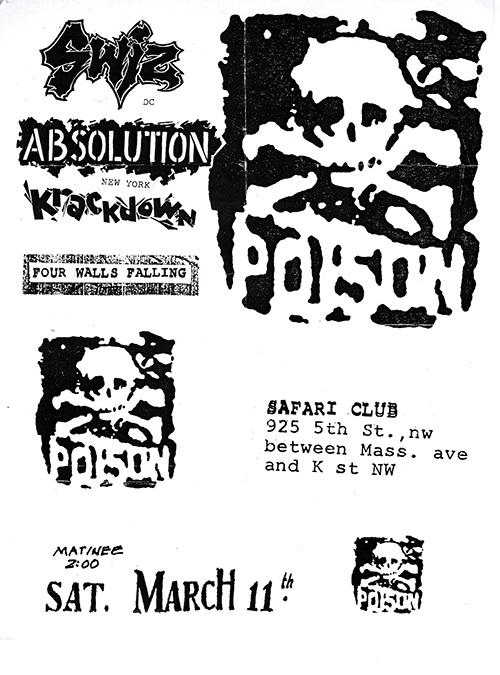

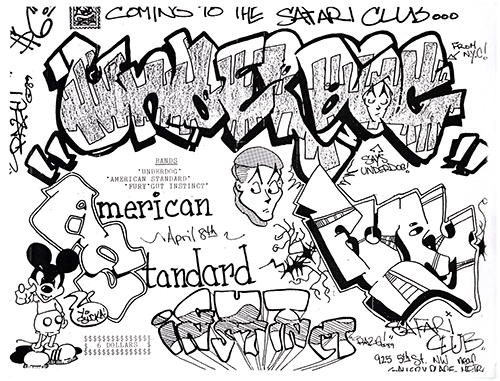

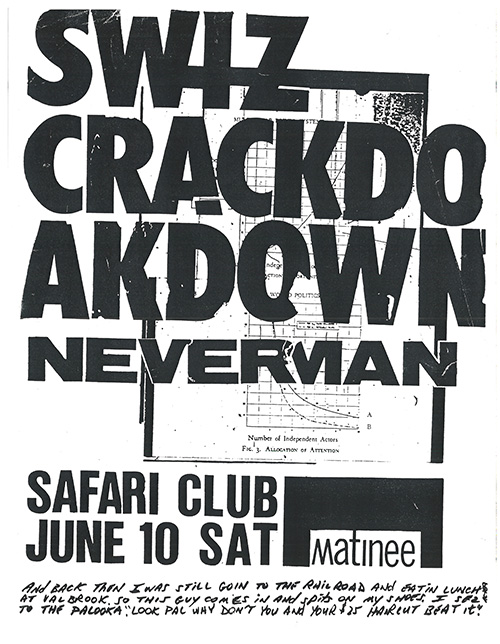

In many corners of the national punk scene, D.C. was still best known for its hardcore scene in the early 1980s. Within D.C., hardcore had long since fallen out of favor but, led by Swiz, a new hardcore scene developed, mostly parallel to the post-hardcore community that rotated around Dischord and the soon-to-bloom indie rock and indie pop communities. Shawna Kenney and Pam Gendell, who edited No Scene fanzine, began booking hardcore concerts at the Safari Club at 925 5th Street NW, near D.C.’s Chinatown neighborhood. “Safari was almost the first steady matinee situation, which was perfect for that crowd,” musician and record producer Ken Olden recalled. “You could tell that kids had almost been waiting for that—kids like us, who were out in the suburbs knowing each other and hanging out with each other but the only other thing you had was the 9:30 Club,” which occasionally booked shows for the likes of New York City hardcore bands such as Cro-Mags or Sick of it All.14 The New York scene remained a profound influence on D.C. hardcore’s second wave as the latter grew into the 1990s.

Even with all of this activity, however, there was still a need to spur on the community and to not let things stagnate. Longtime scene participant Sharon Cheslow published a new fanzine, Interrobang, in December and its opening editorial offered a fitting challenge to end the year:

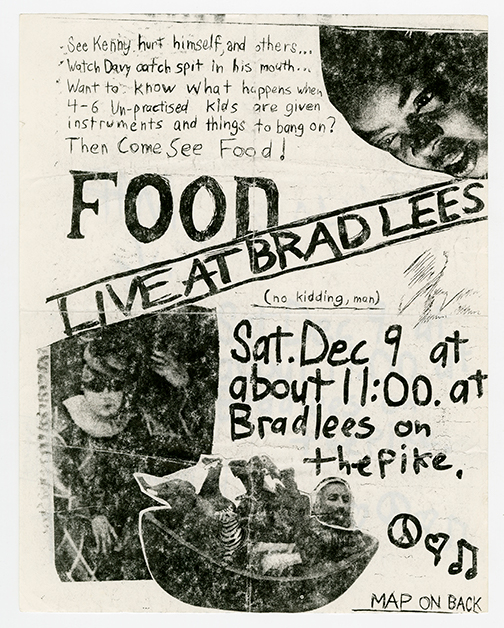

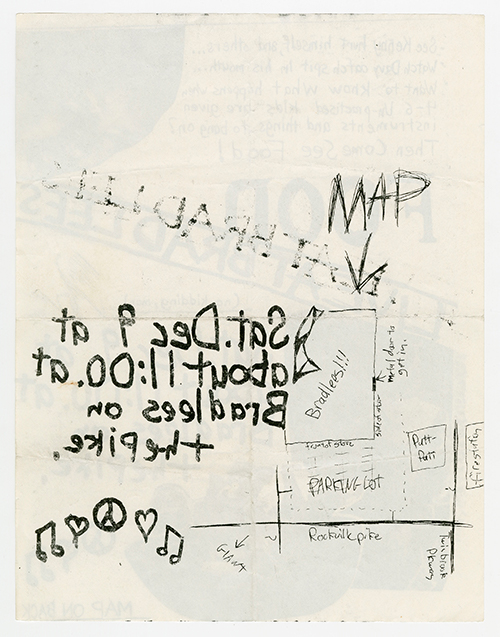

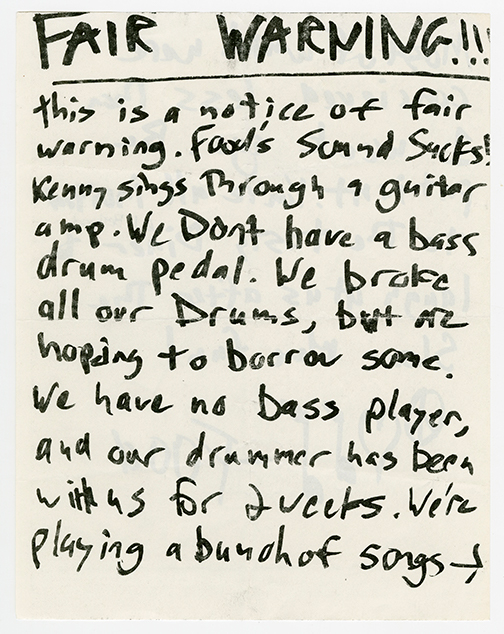

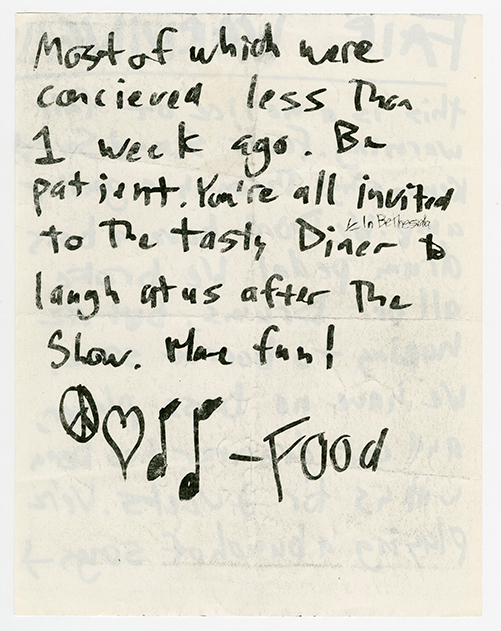

Don’t become part of the society we all hate–the part that is apathetic and content with the status quo. Pick up an instrument, start a band, write a fanzine (or even a book), make a film, take photographs, volunteer, give things away that you don’t need, start a label, let bands play in your basement, put on a show at your local community center (or high school or YMCA or wherever–and make lots of flyers)...Don’t wait for someone else to do it…Act now!15

Further Listening

Edsel. “My Manacles”/”Wooden Floors.” DeSoto Records, 7-inch single.

Thee Evolution Revolution. E/Bone. Get Hip Records, 7-inch single.

Fidelity Jones. Piltdown Lad. Dischord Records, 12-inch EP.

Fire Party. New Orleans Opera. Dischord Records, album.

Fugazi. Margin Walker. Dischord Records, 12-inch EP.

Fugazi. 13 Songs. Dischord Records, album.

Holy Rollers. Origami Sessions. Dischord Records/Adult Swim Records, 7-inch EP.

Ignition. The Orafying Mysticle Of.... Dischord Records, 12-inch EP.

Jawbox. Jawbox. Self-released demo cassette.

Soulside. Hot Bodi-Gram. Dischord Records, album.

Swiz. Hell Yes I Cheated. Sammich Records, album.

Three. Dark Days Coming. Dischord Records, album.

Various. State of the Union. Dischord Records, compilation LP.

Vile Cherubs. Post-Humorous Relief. Dischord Records/Cherubic Delusions, album.

Materials are drawn from the Paul Bushmiller collection on punk, the Sharon Cheslow punk flyers collection, the D.C. punk collection, the Jason Farrell collection, and the Robbie White collection on the Slickee Boys.

Tap or hover over an image to learn more.

FLIERS

ZINES

EPHEMERA