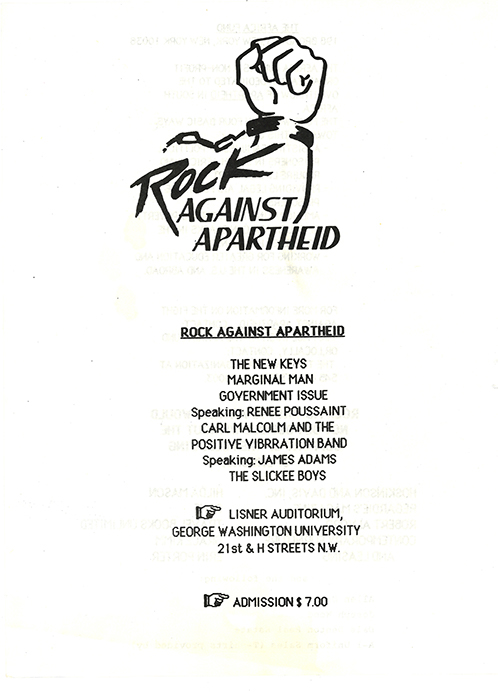

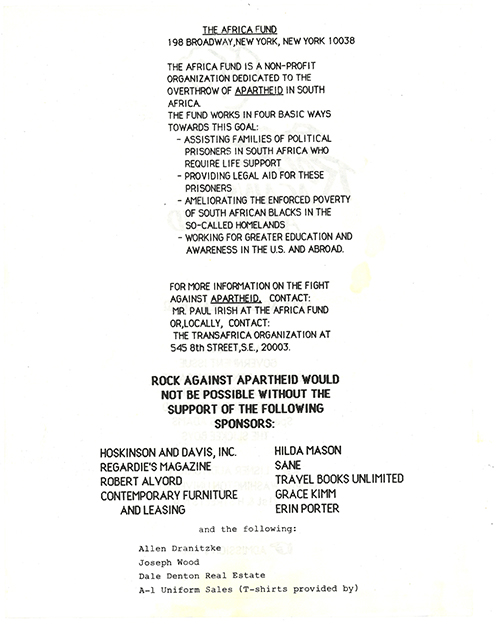

The previous year’s organizing and musical transformation within the D.C. punk community created a sense of progress and possibility, which made the contrasting state of global political affairs seem especially bleak. President Reagan vetoed the bipartisan Anti-Apartheid act—a veto which, in turn, was overidden—which pursued sanctions against the South African government for its continual support of apartheid policies.1 Increasing tensions with Libya flared on April 15, when eighteen American attack aircraft dropped sixty tons of munitions on Libyan targets, killing soldiers and civilians. The attack was described by American officials as a response to a recent bombing in Germany that had killed and injured American soldiers which, along with other terrorist attacks, the Reagan administration blamed on Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi.2

What stands out perhaps most of all about 1986 is the nationalization of issues surrounding cocaine in the United States. Use of the drug expanded rapidly nationwide and, in the District, open-air drug markets foreshadowed the havoc of the coming years.3 National discourse, however, centered on crack cocaine, which was presented as a novel substance, despite the only novelty about the form of cocaine being its relatively low cost compared to powdered cocaine.4

The tragic, drug-related death of Prince George’s County native Len Bias on June 19 became one of the year’s most notable stories. Bias was a standout basketball player at the University of Maryland and was chosen with the second overall pick in the NBA draft by the Boston Celtics following his senior year. A cocaine overdose killed him just days after his NBA selection and the shocking nature of his death quickly triggered “a torrent of stories in magazines from Sports Illustrated to Good Housekeeping to Life,” according to journalists Harry Jaffe and Tom Sherwood.5

...

The furor in the press agitated the public, which left politicians scrambling to appear as if they were doing something about the growing problem. Reagan’s signing of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, also referred to as the “Len Bias Law,”6 established sentencing that was one hundred times more stringent for crack cocaine than for powdered cocaine. The move was ostensibly centered on the “epidemic” at hand but, in action, created an explosive wave of incarceration as an extension of the country’s unequal and racialized drug policy.7 Reagan and his wife, Nancy, repeatedly spoke out against drug use—Nancy Reagan’s frequent media appearances propagating the infamous “Just Say No” slogan were ubiquitous—yet the Reagan administration slashed funding for drug treatment and prevention programs by forty percent from 1980 to 1986.8

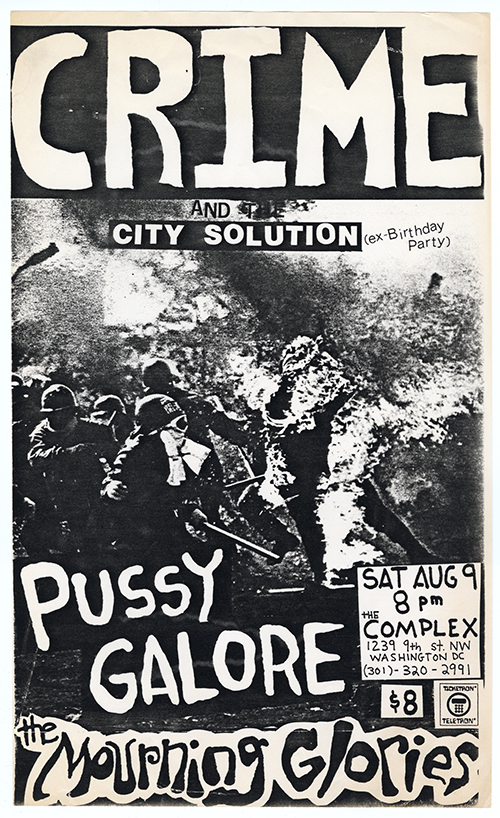

Amidst the friction and frustration of the mainstream world, the D.C. punks who looked to prolong the feeling of 1985’s “revolution” found their mission proved difficult. Before 1986 was out, most of the core bands from the Revolution Summer period had broken up, generating a feeling of loss and uncertainty for those who cared and a not-insignificant amount of schadenfreude among those who rolled their eyes at the earnestness of the previous year’s efforts. “That whole ‘Revolution Summer’ thing just fell flat on its face,” smirked Jon Spencer, whose band Pussy Galore got started in D.C. in 1985 before moving to New York City the next year.9 Pussy Galore one-upped earlier contrarian D.C. punk bands Psychodrama and No Trend by naming one of their songs “Fuck You, Ian MacKaye” before splitting town, leaving a cloud of brimstone fumes in their wake.

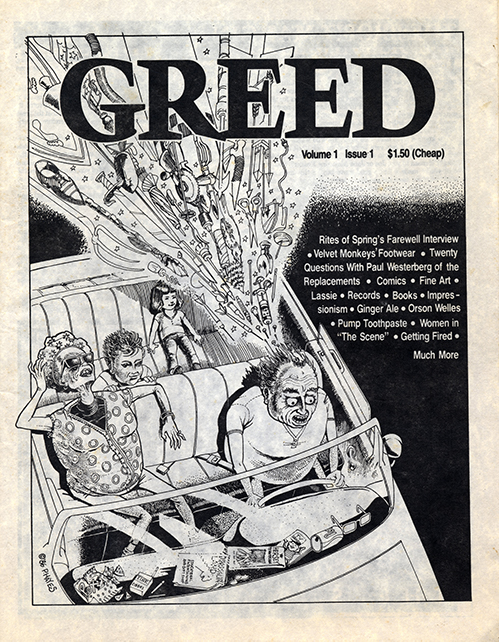

Kurt Sayenga’s fanzine Greed debuted in 1986 and its first issue features an interview with the recently defunct Rites of Spring’s Guy Picciotto, Brendan Canty, and Eddie Janney. The trio reflected on their shared sense of loss following the breakup of the band, but also were dismissive of the idea that their efforts were for naught. “It feels like everything you’ve done is destroyed, but it’s not true,” Picciotto said. “The shows existed, the people came out to the shows, I played the shows, the record came out—it’s just changed my whole life.”10 These feelings also extended beyond mourning just the end of Rites of Spring, with Picciotto later responding to worries about the local punk subculture’s durability:

People talk about the death of the scene or how music is dying, but no matter where you are, you’ll find people who know what they are doing, and you’ll also find people who don’t know what they’re doing and are just wearing clothes. […] There’s always been a high caliber of bands and a high caliber of people and I don’t think it can be taken away by people acting stupidly.11

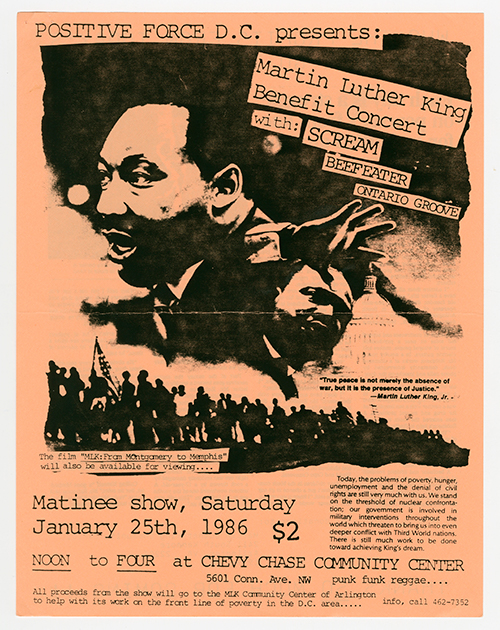

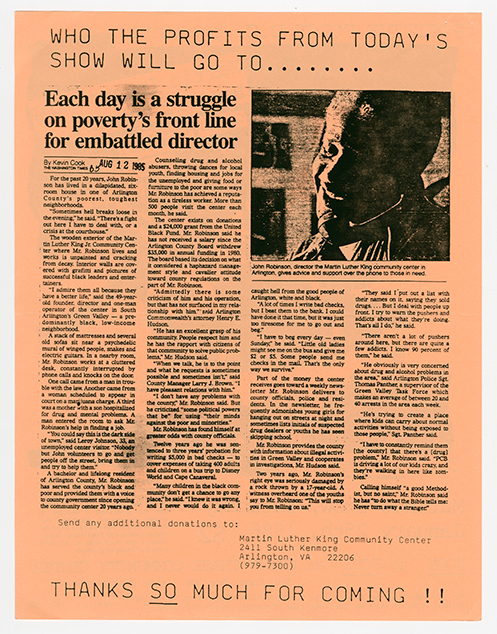

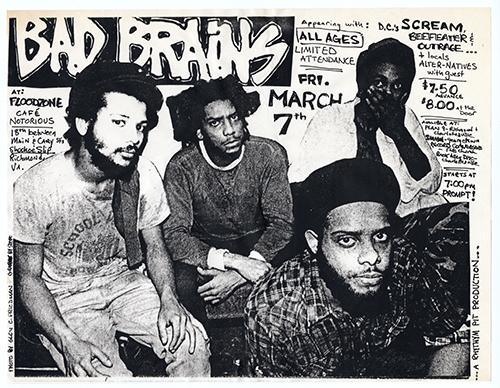

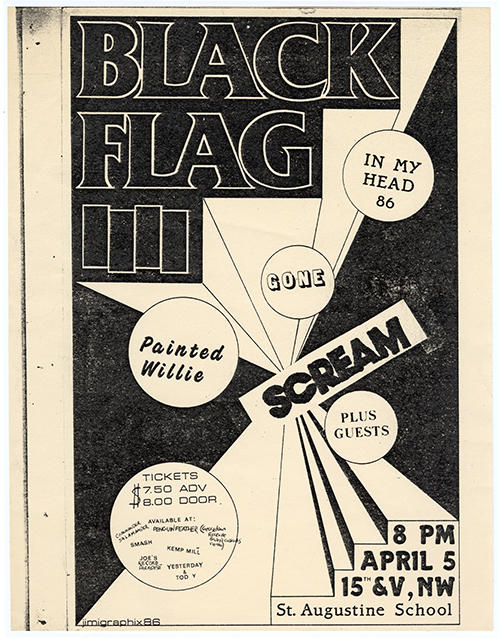

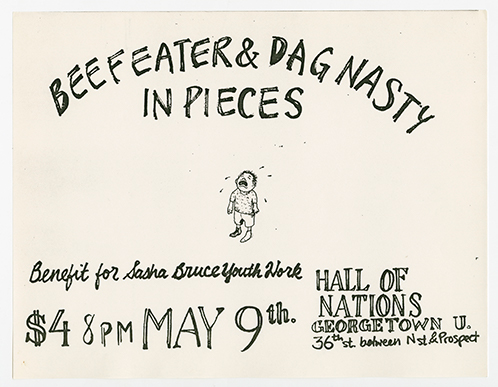

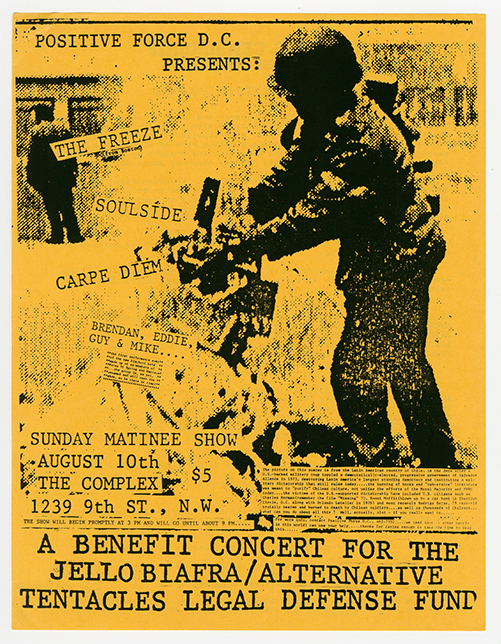

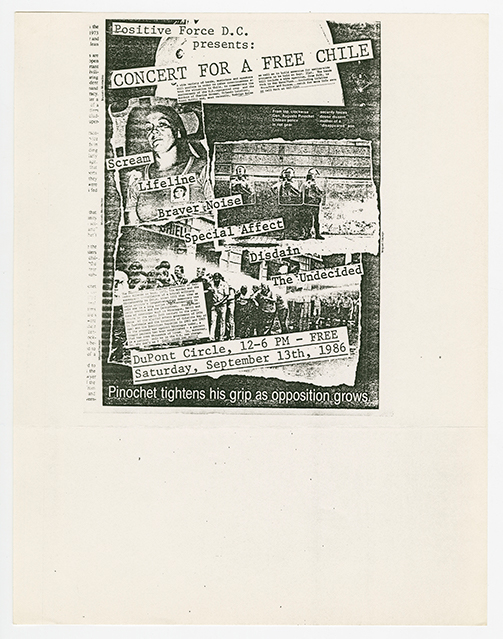

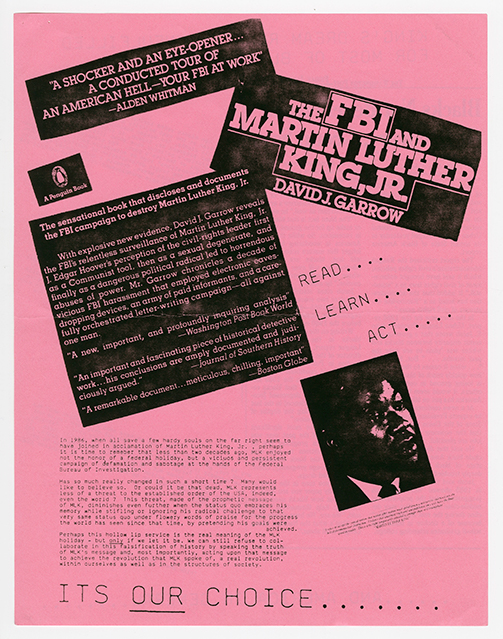

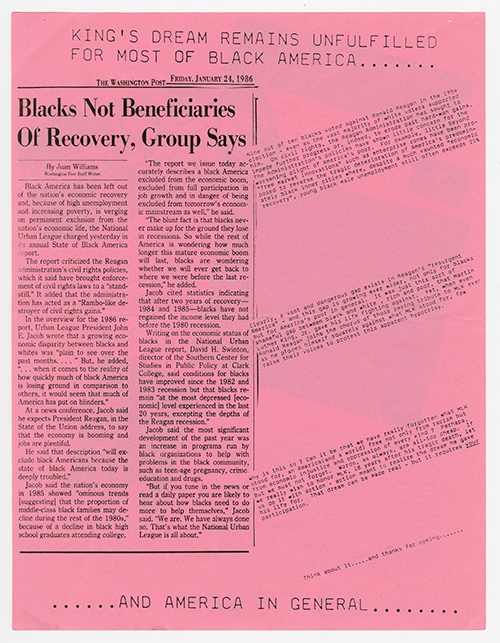

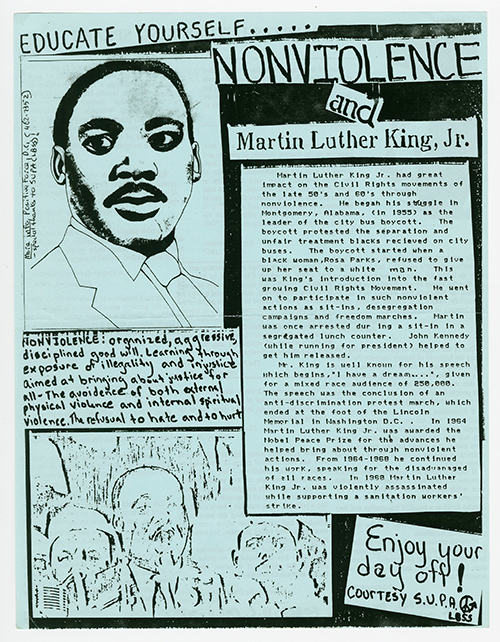

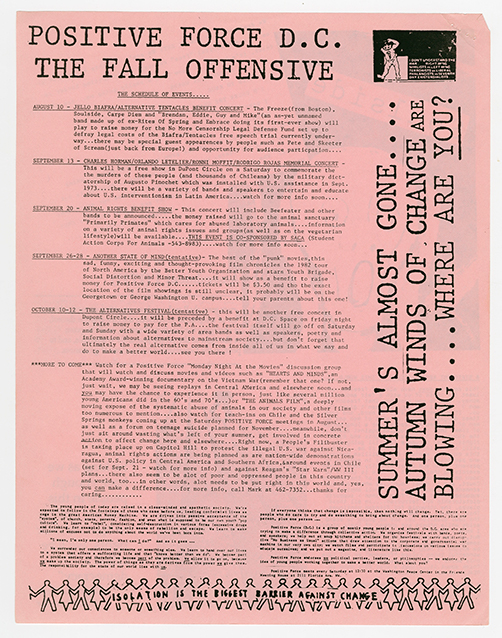

Revolution Summer provided an opportunity for a greater sense of musical freedom and a reaffirmation of music as a potent political force. This momentum continued into 1986, beginning with the first Positive Force-organized benefit of the year on January 25, when Scream and Beefeater performed at the Chevy Chase Community Center. Positive Force DC had formed in June 1985 and the activist group began organizing a string of what would become ubiquitous benefit shows oriented around local and global causes. The January 25th show was on behalf of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Community Center in Arlington, Virginia and coincided with the first celebration of the new federal holiday, Martin Luther King Jr. Day. The concert was promoted by fliers packed with information on the holiday and the larger continuing struggle for civil rights. Surrounded by cutouts from the front and back covers of David J. Garrow’s "The FBI and Martin Luther King Jr.," one handout produced for the event provides context for the holiday and an insistence that the day not become a hollow remembrance of Dr. King. Rather, the text asks of the reader a day for action towards King’s revolutionary ideals, achieved through “speaking the truth of MLK’s message and, most importantly, acting upon that message to achieve the revolution that MLK spoke of, a real revolution, within ourselves, as well as in the structures of society.”

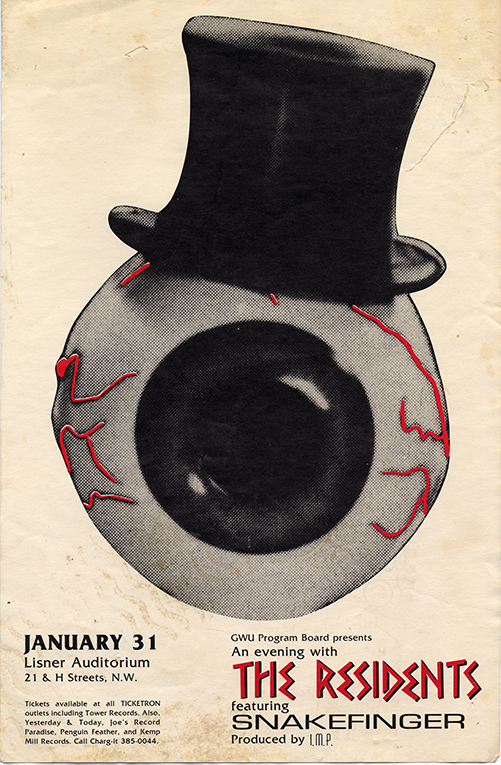

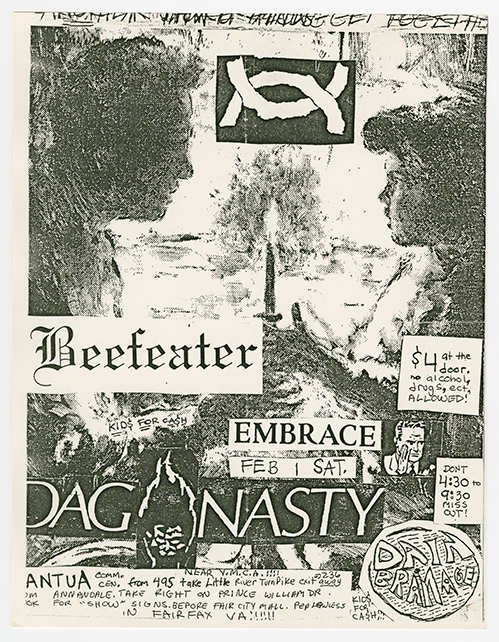

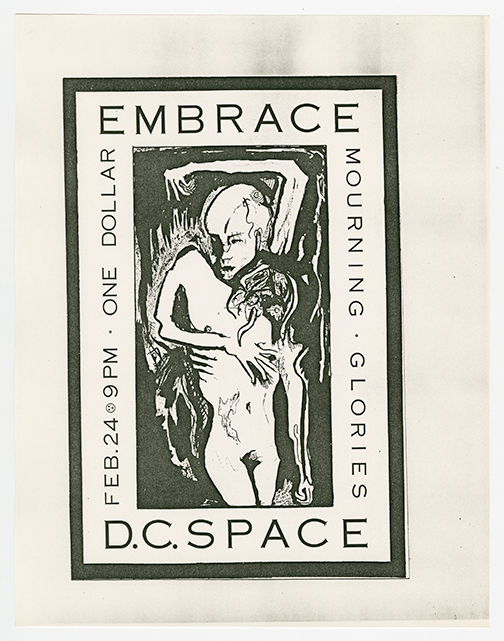

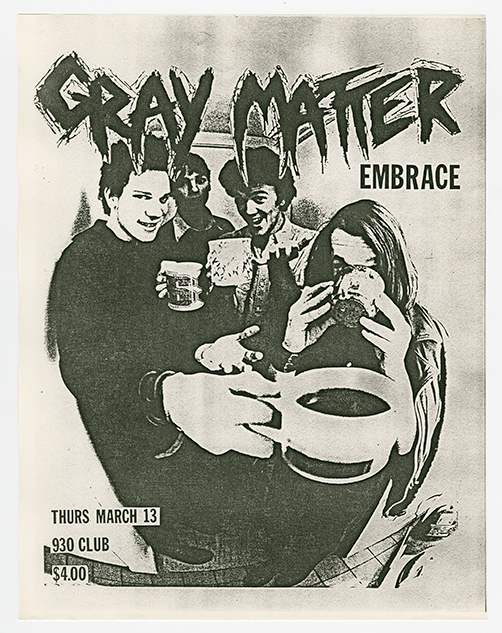

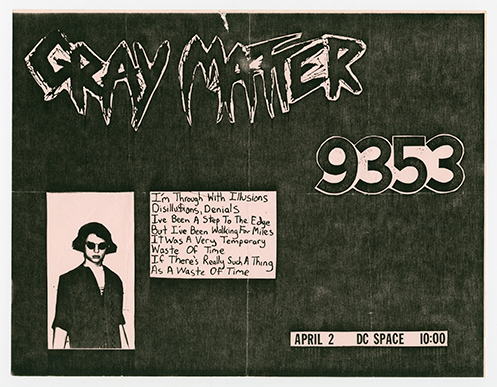

The stylistic musical shifts brought about through the summer of 1985 continued to reverberate and can be seen in the print material from the year. Embrace’s fliers from their January 30th and February 24th concerts mirror the fluid and poetic shift the music had taken. Rather than the jagged scissor work of earlier cut-and-paste fliers, Embrace’s fliers featured soft brush strokes and ethereal figures blending into saturated blocks of darkness. Like Rites of Spring, Embrace disbanded in early 1986, with the group playing its final concert on March 13 at the 9:30 Club with Gray Matter. Embrace’s internal chemistry had always been somewhat elusive. “Embrace played a few shows … but there was always a sense that things just weren’t jelling the way they should,” guitarist Michael Hampton recalled. “It was not the band that I think Ian wanted to be in. It eventually became the band that none of us wanted to be in. Everything was just too hard in Embrace.”12 Hampton soon joined former Rites of Spring members Picciotto, Janney, and Canty—the quartet lived together in a group house near the Washington National Cathedral in upper NW D.C.—in the promising new band One Last Wish.13 That group, too, collapsed quickly, playing only a handful of shows throughout 1986 before disbanding. An album worth of songs was recorded in November but it did not see official release until Dischord and Picciotto’s label, Peterbilt, co-released it in 1999 with the apt title of 1986.

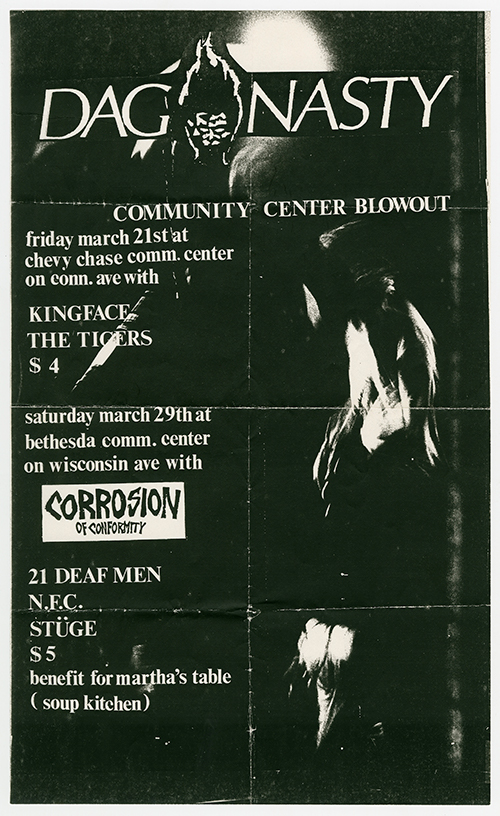

Gray Matter and Beefeater also broke up in 1986, though Gray Matter would reunite for a second stint in the early 1990s. The implosion of so many of the scene’s core bands was a key point in the ridiculing of Revolution Summer, yet the immediate legacy of 1985 was already becoming clear, even if Rites of Spring, Embrace, and the other bands that helped change the scene’s direction in 1984 and 1985 had ended. Another burst of activity was evident by the end of 1986, with a number of new bands forming that would become major presences in the latter half of the decade, including Fire Party, Shudder to Think, Soulside, and Ignition. These groups clearly aimed to build upon what the Revolution Summer bands had started. Music was to be a sincere expression that aimed to challenge and change the listener, as well as the musicians themselves. Perhaps, even the world around them. As had now become routine, the year was punctuated by the end of a movement dovetailing into the beginnings of the next.

Further Listening

Beefeater. House Burning Down. Dischord Records, Album.

Beefeater. Need a Job. Olive Tree Records, 12-inch EP.

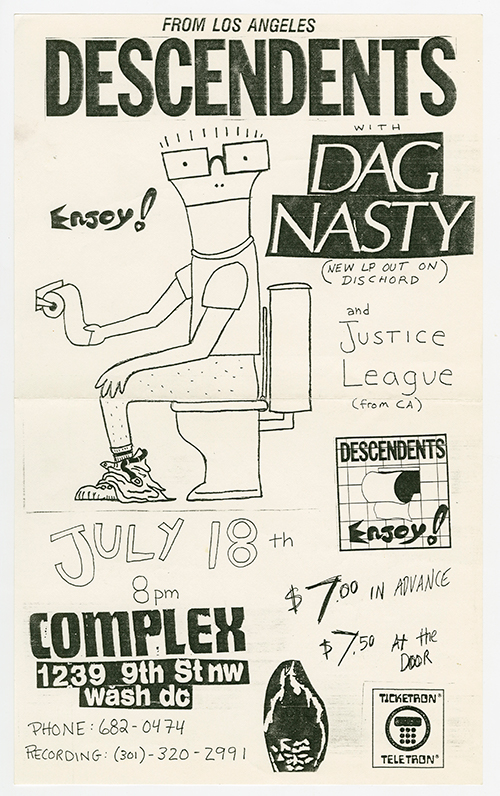

Dag Nasty. Can I Say. Dischord Records, Album.

Egg Hunt. Me and You. Dischord Records, 7-inch single.

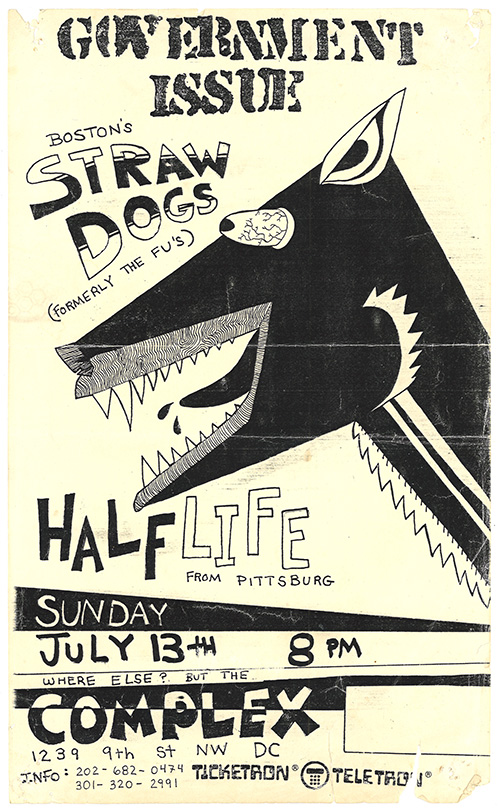

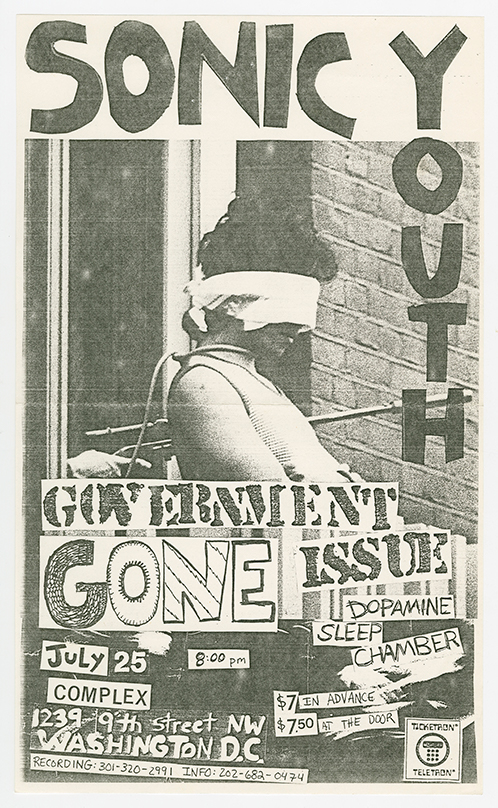

Government Issue. Government Issue. Fountain of Youth Records, Album.

Gray Matter. Take It Back. Dischord Records, 12-inch EP.

Pussy Galore. Groovy Hate Fuck. Shove Records, 12-inch EP.

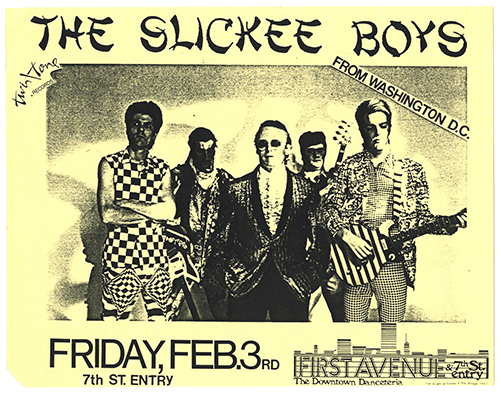

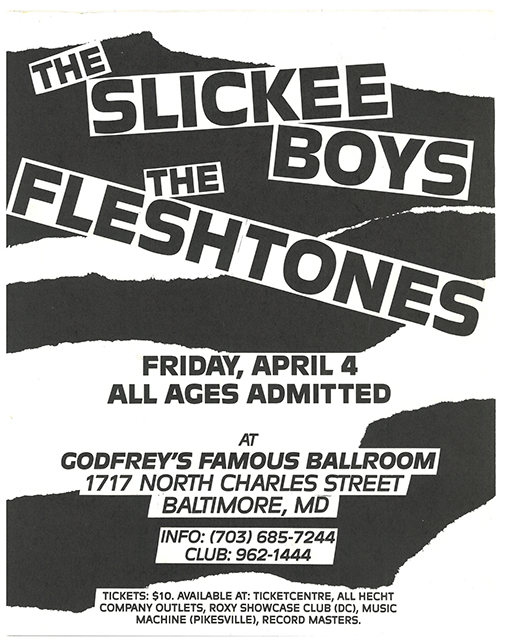

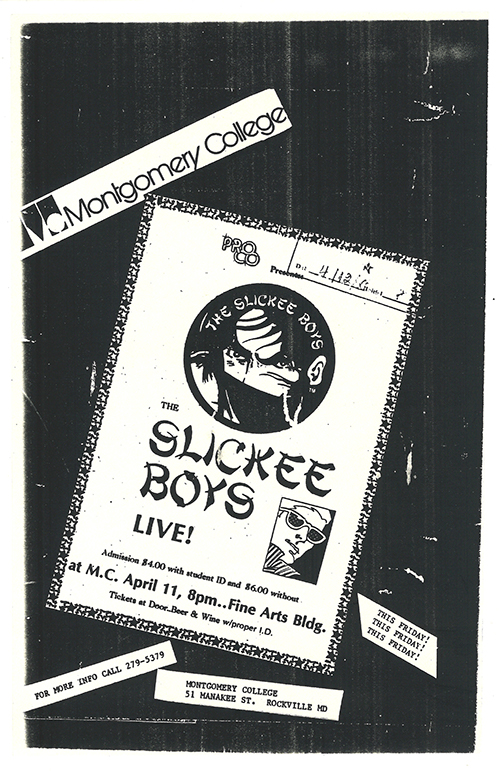

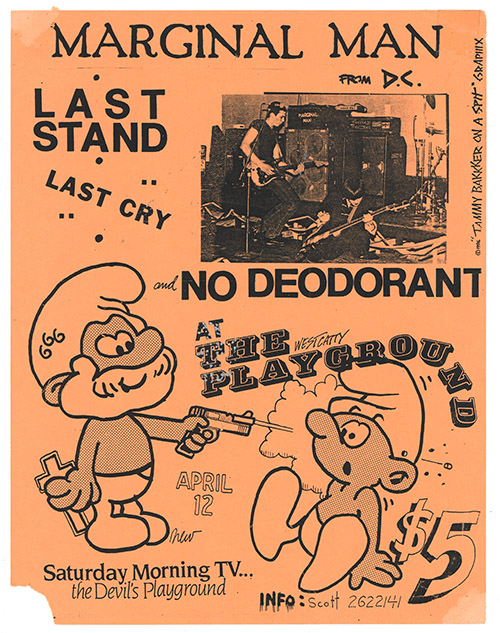

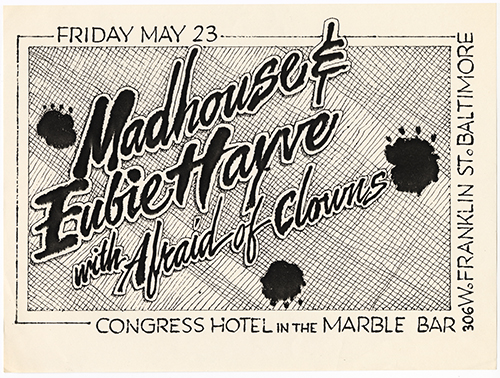

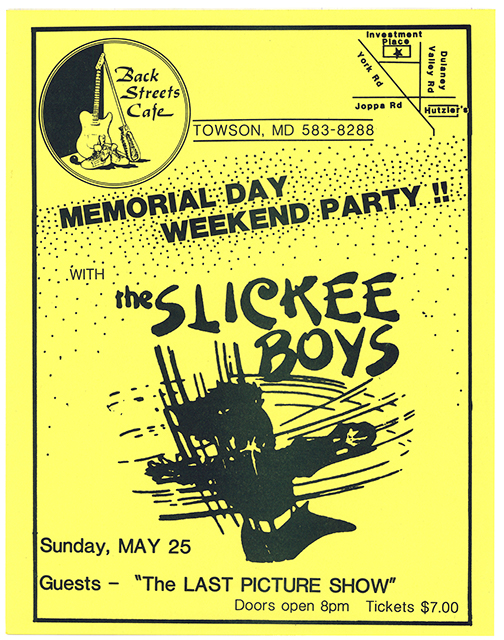

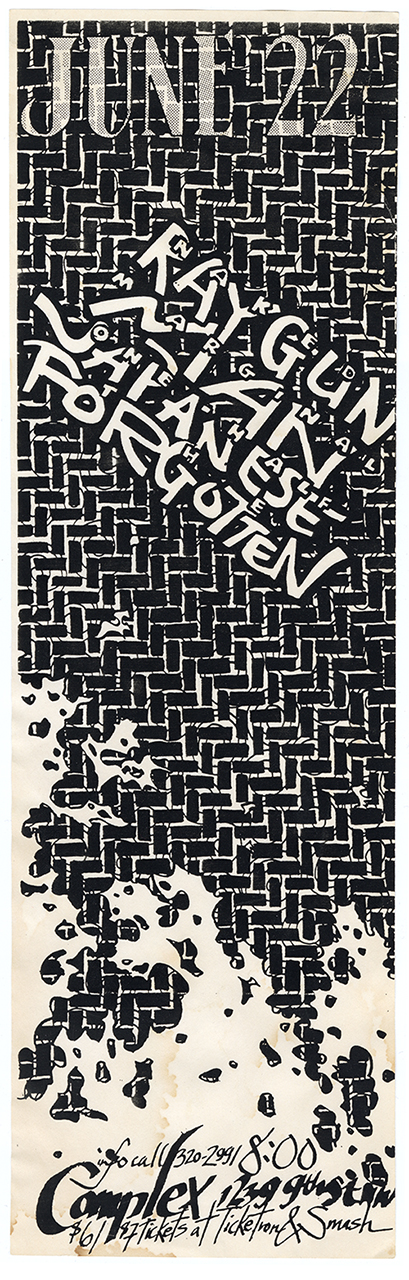

Materials are drawn from the Paul Bushmiller collection on punk, the Sharon Cheslow punk flyers collection, the D.C. punk collection, the D.C. punk and indie fanzine collection, the Skip Groff papers, and the Robbie White collection on the Slickee Boys.

Tap or hover over an image to learn more.

FLIERS

ZINES

EPHEMERA

RECORDINGS

The Mourning Glories and B-Time concert recordings, 9:30 Club, Washington, D.C., May 28, 1986 and June 13, 1986