A note on content: This essay includes profanity and references to homophobic, racist, and antisemitic language and behavior.

Twin tragedies, separated by only thirty minutes, presented a grim opening to 1982 in Washington, D.C. The crash on January 13 of Air Florida 90 into the 14th Street bridge killed seventy-eight, followed by the derailing of a Metro subway train near the Federal Triangle stop in DC, claiming three lives. Despite the year’s unsettling beginnings and the city’s growing debt, things were looking up for Mayor Marion Barry. Still widely popular, Barry solidified his political power in 1982, winning his first reelection bid, defeating E. Brooke Lee. As further cause for optimism, Barry’s first term was marked by a boom in development of commercial space downtown and by his support of the city’s summer jobs program for school-age residents, which helped thousands of young Washingtonians get their first job.1, 2

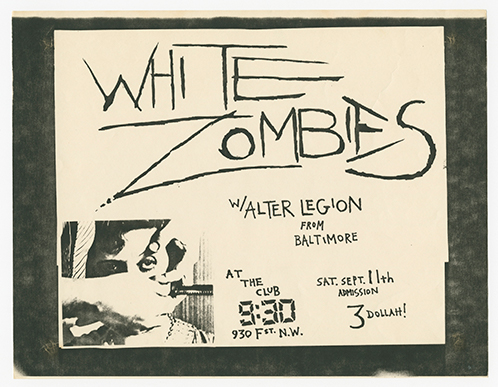

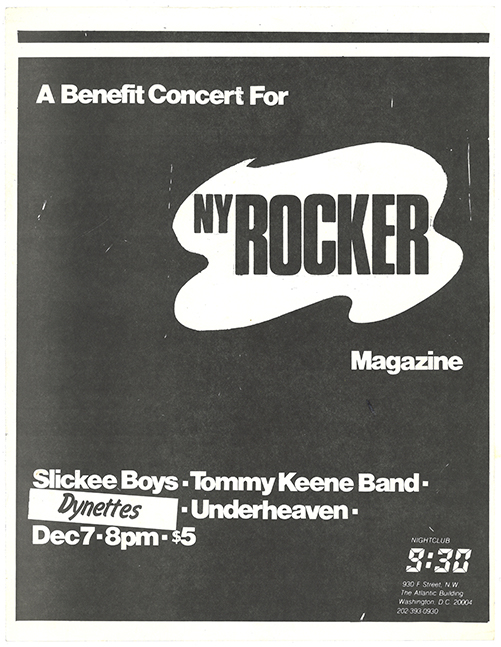

Nationally, 1982 also saw a name–Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS)–applied to the pandemic that continued spreading, yet mainstream media attention remained scarce. Widespread public indifference led to a rise in AIDS service organizations, developed from existing and newly formed organizations within LGBT communities, such as the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (now GMHC) in New York City and the Los Angeles Gay and Lesbian Center (now Los Angeles LGBT Center). By 1982, D.C.’s own Whitman-Walker Clinic, which opened nearly a decade earlier out of the basement of the Georgetown Lutheran Church had moved to 18th Street NW and expanded its services. Later in the decade, the clinic became a regular recipient of proceeds from benefit concerts that D.C. punk bands put together, reflecting the scene’s increased social activism in the second half of the 1980s.3

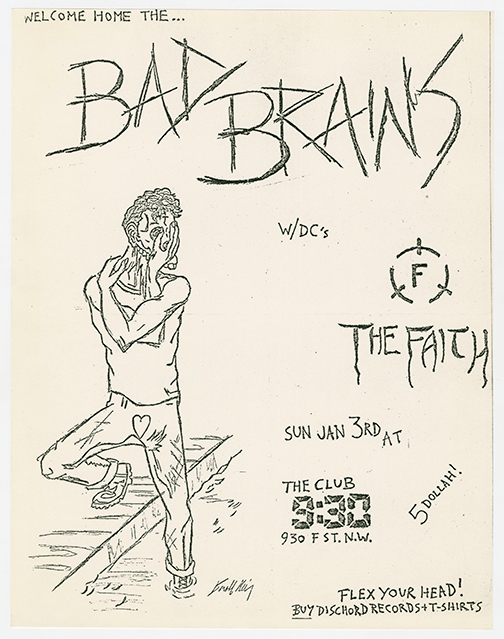

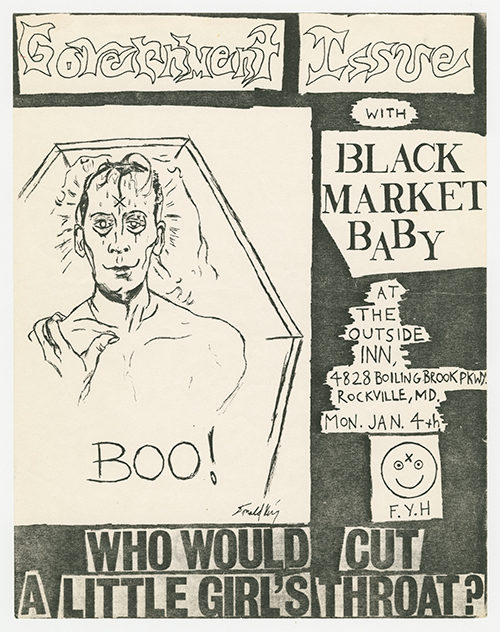

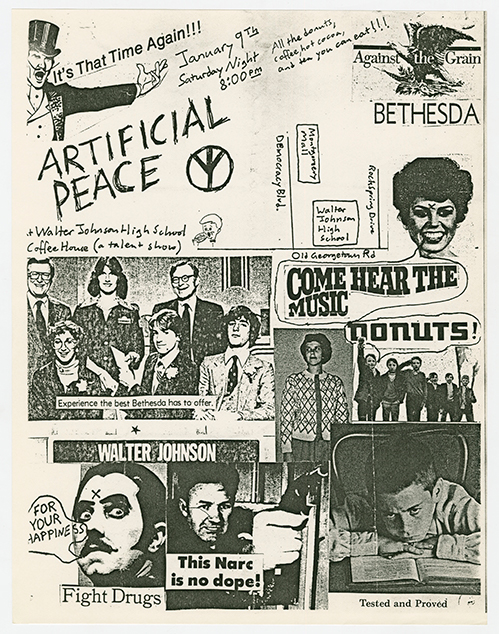

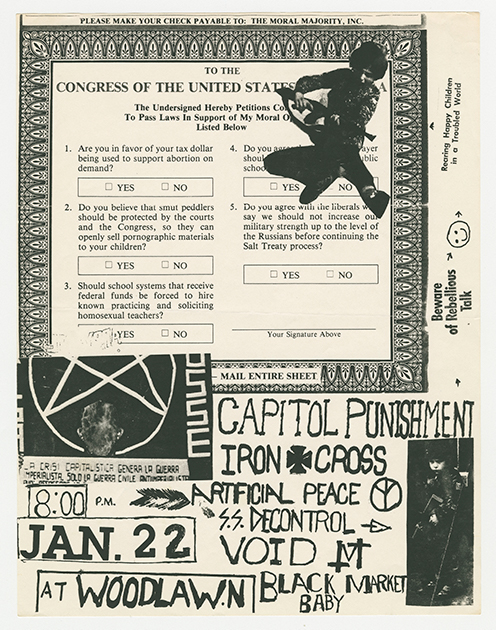

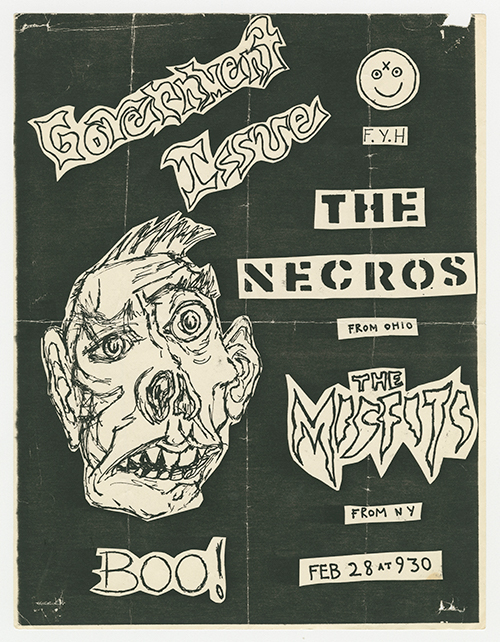

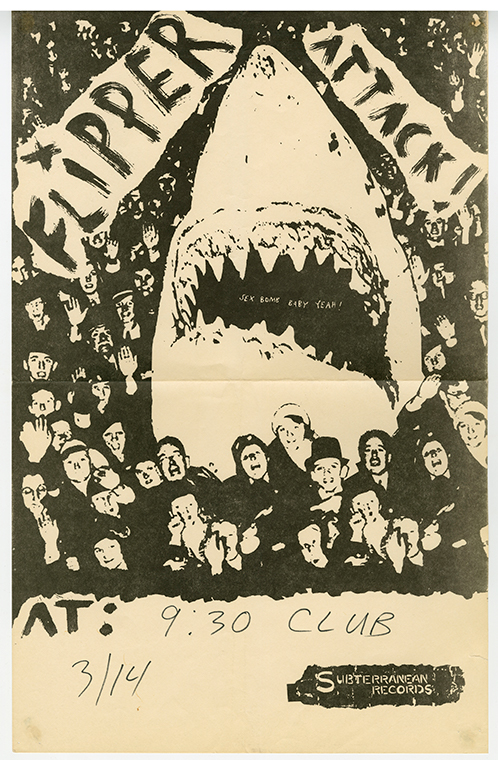

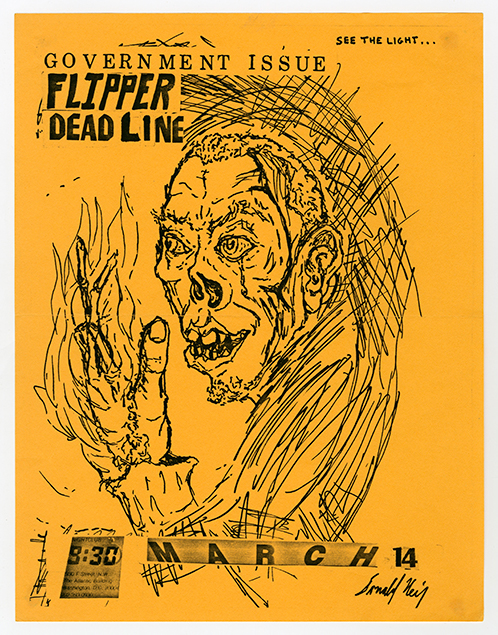

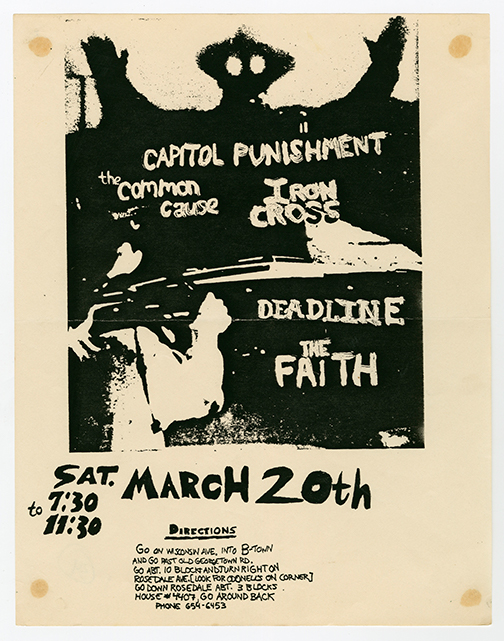

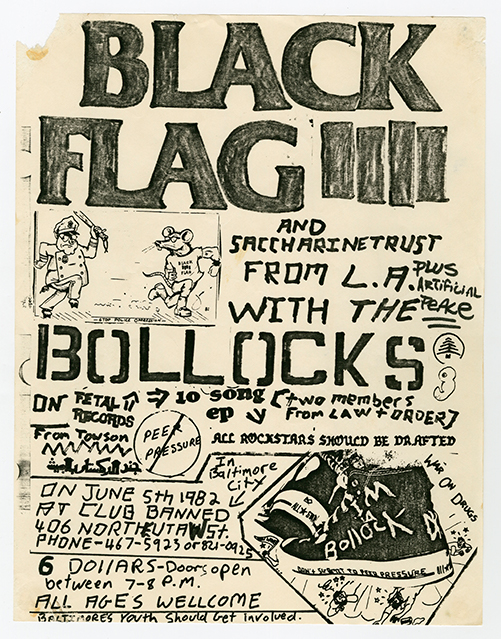

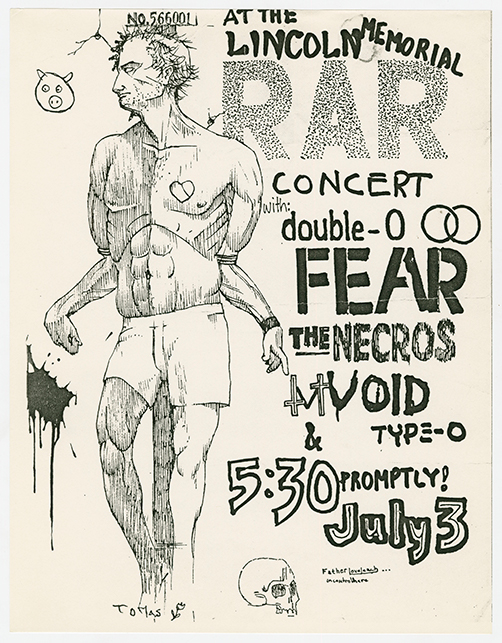

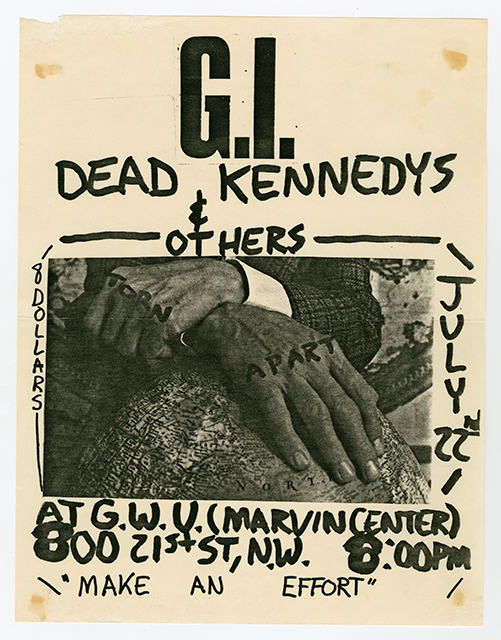

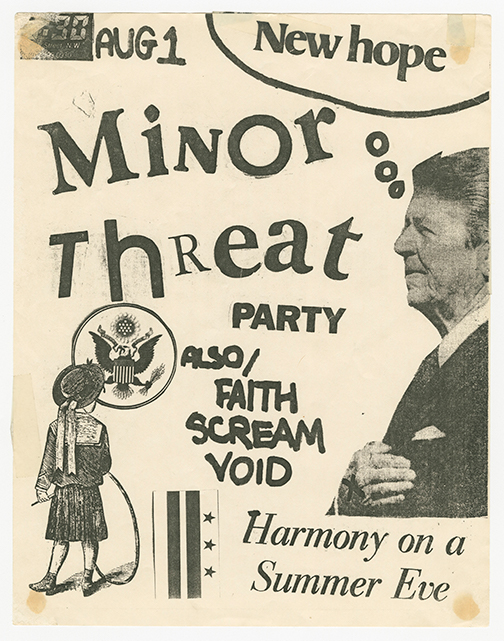

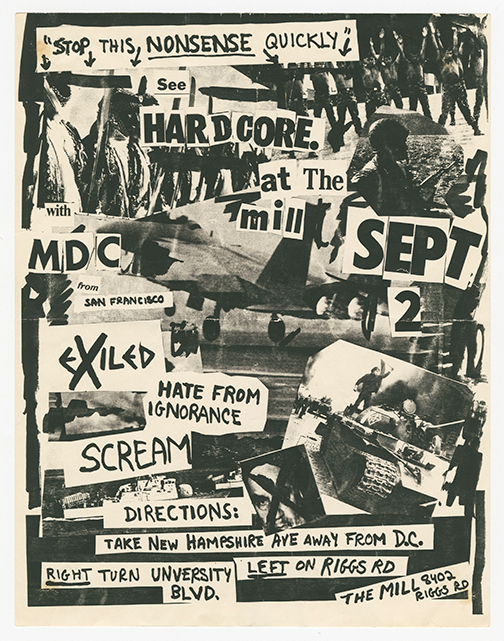

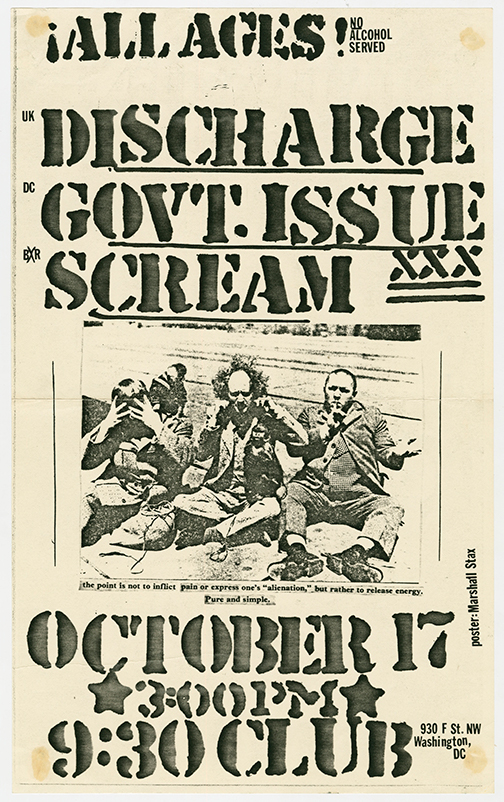

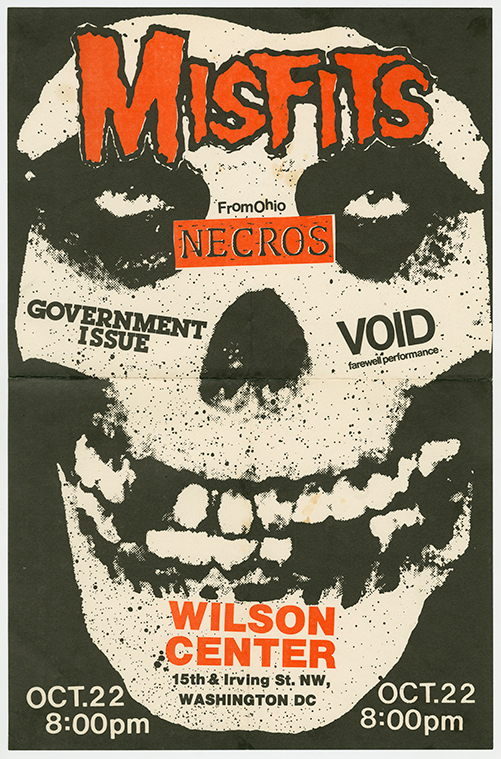

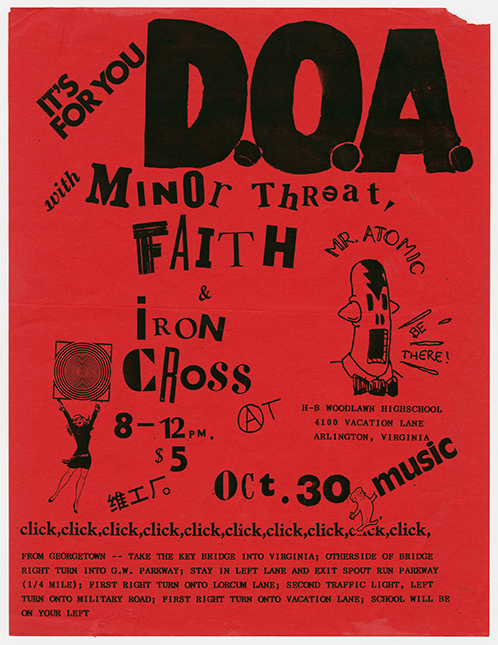

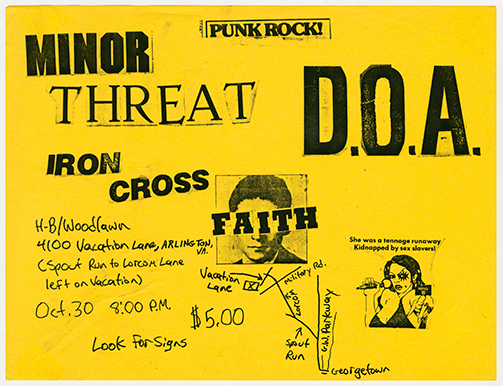

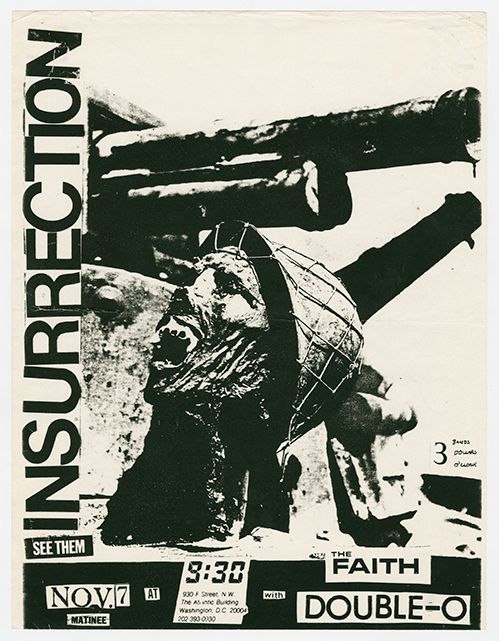

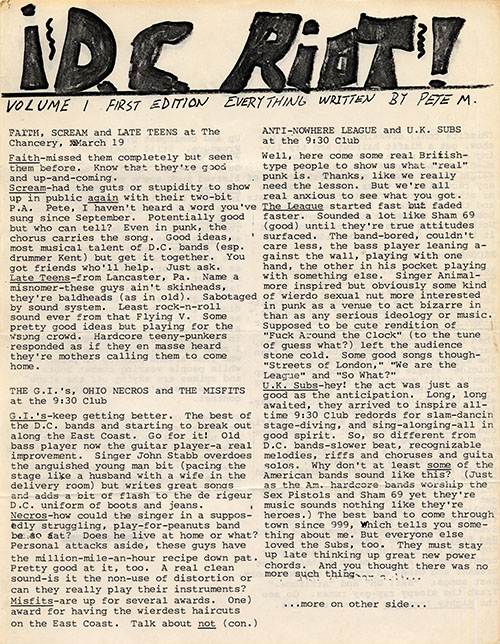

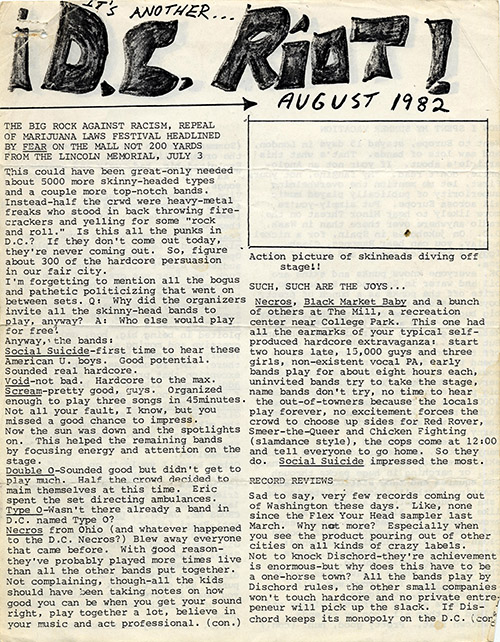

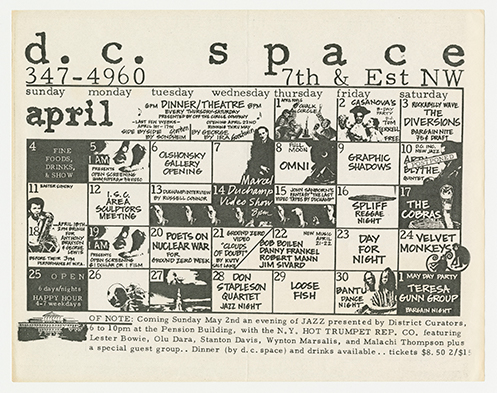

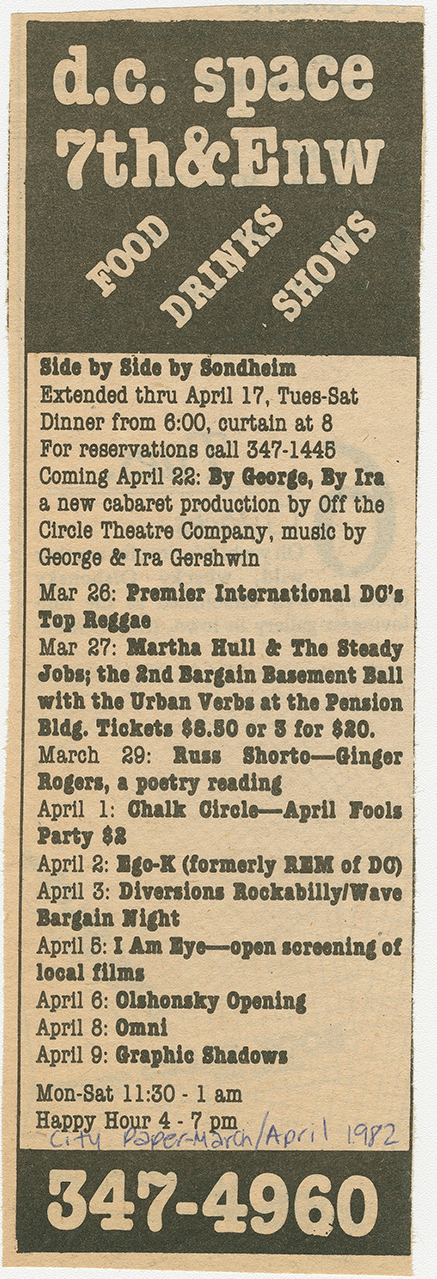

Within D.C. punk, 1982 demonstrated that the city's hardcore scene had fully arrived with the landmark Dischord releases of the Faith/Void split LP and the compilation, Flex Your Head. Faith/Void exhibited two of the community’s defining bands, each occupying a side of the split LP. Faith/Void would later prove widely influential within punk and metal, but it was Flex Your Head that immediately announced the D.C. scene to the larger punk community. Featuring the the Teen Idles, the Untouchables, State of Alert, Minor Threat, Government Issue, Youth Brigade, Red C, Void, Iron Cross, Artificial Peace, and Deadline, Flex Your Head circulated widely and became a defining artifact of American hardcore punk.

...

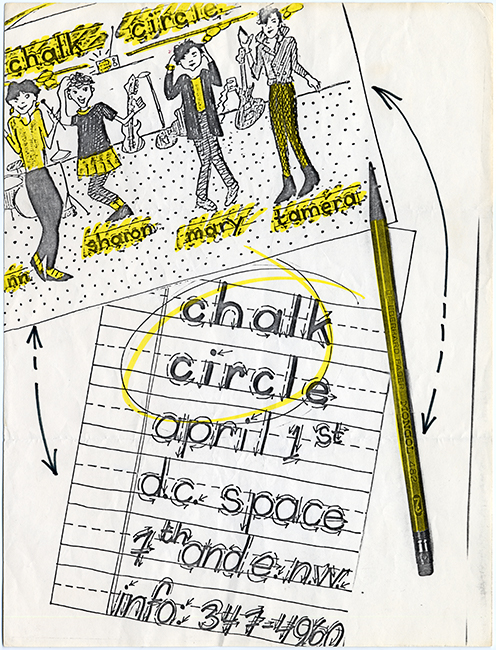

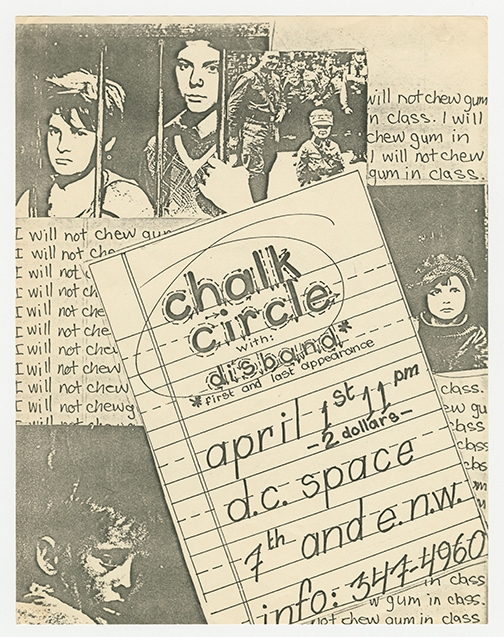

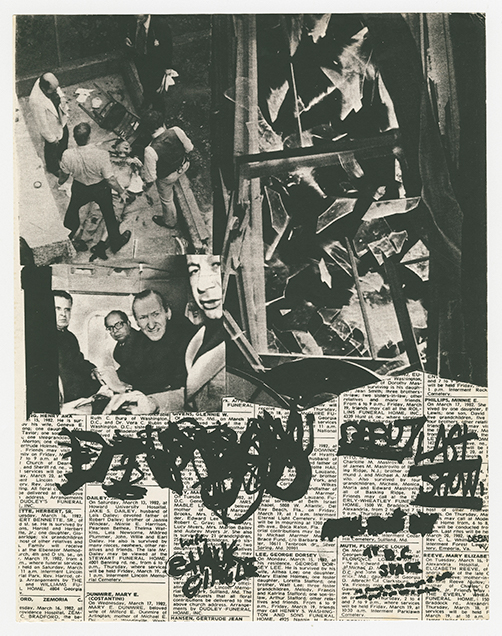

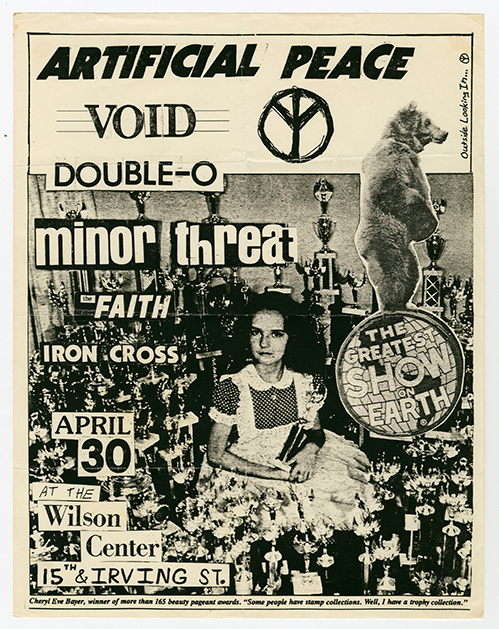

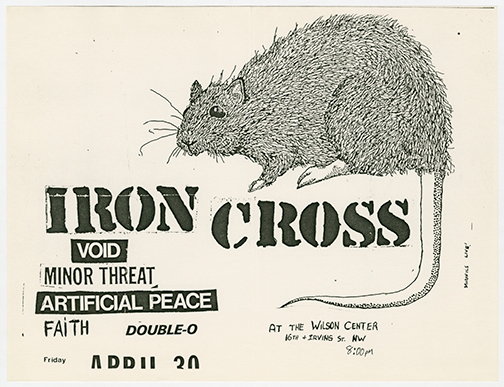

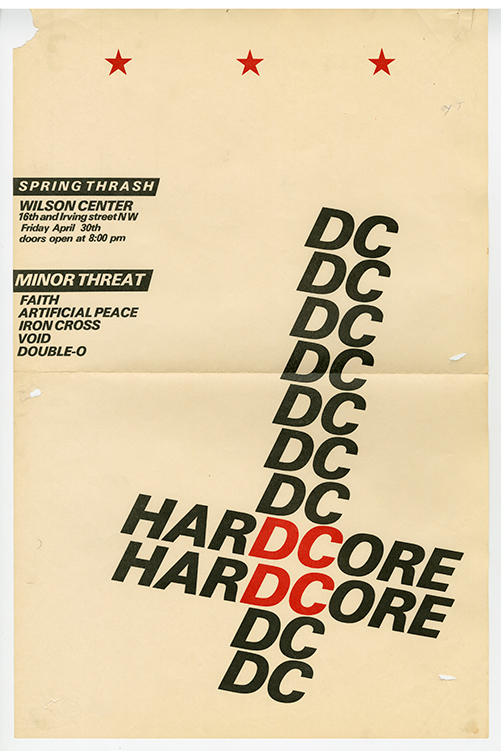

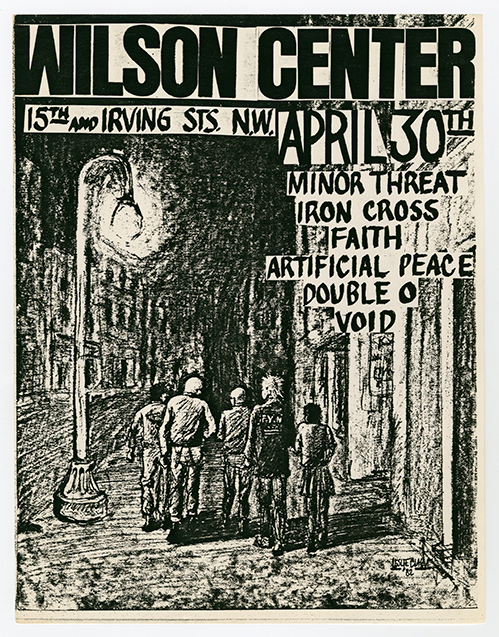

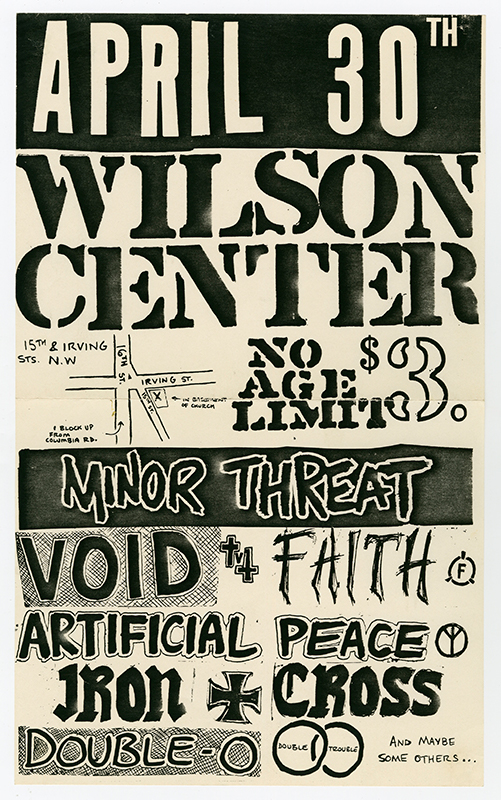

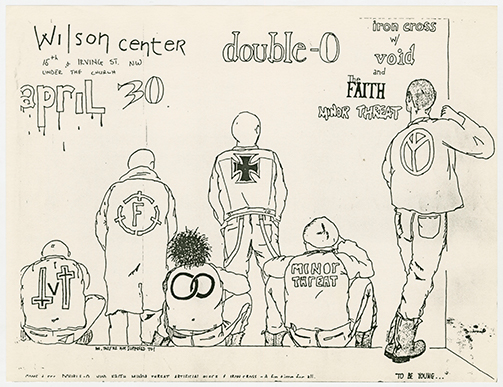

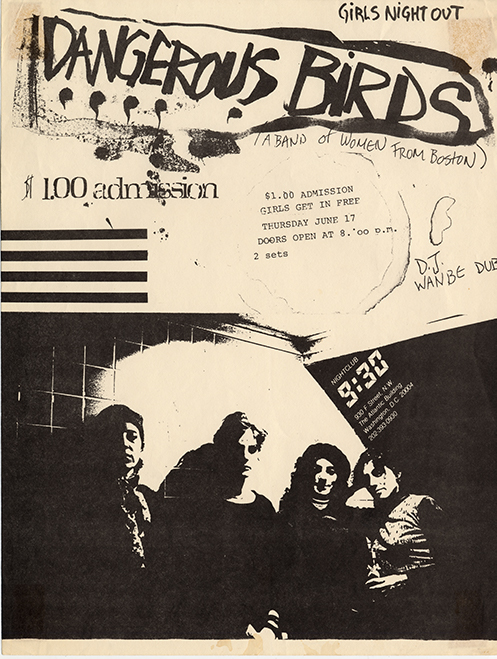

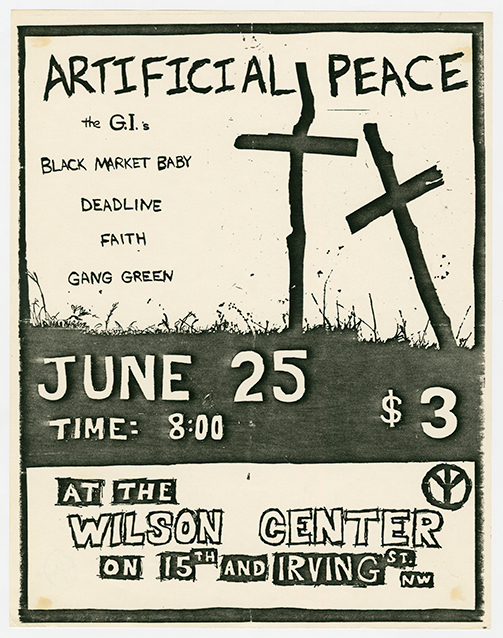

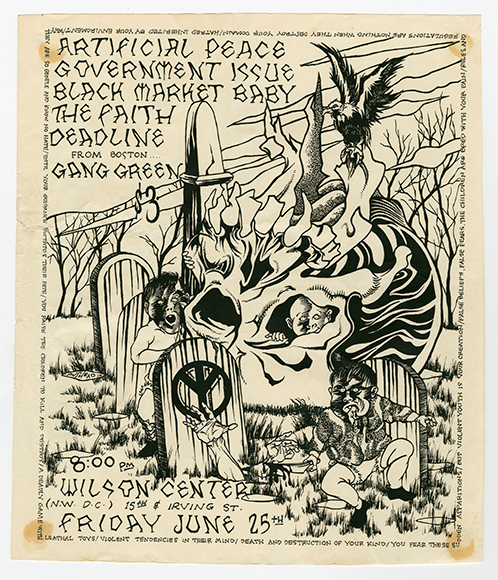

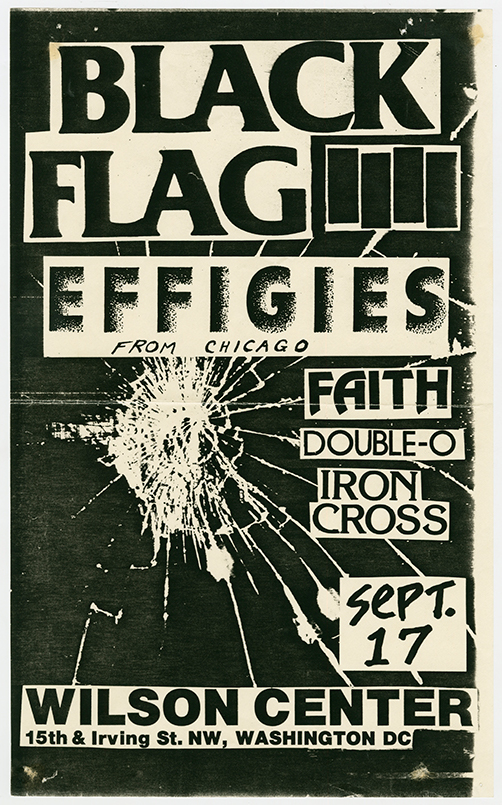

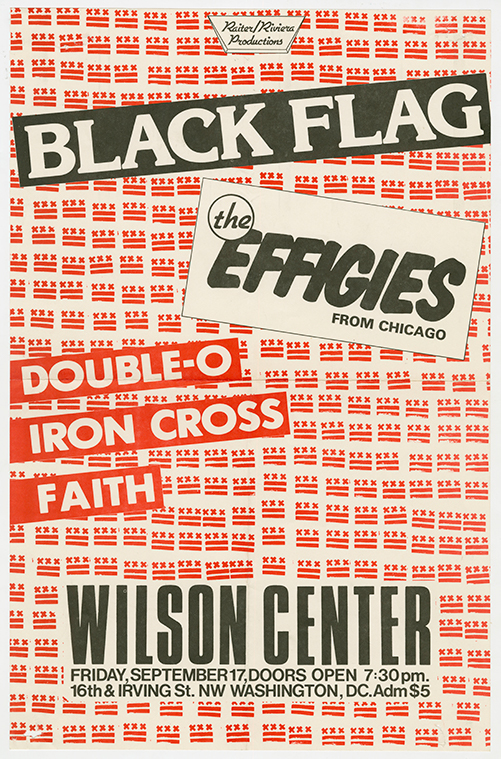

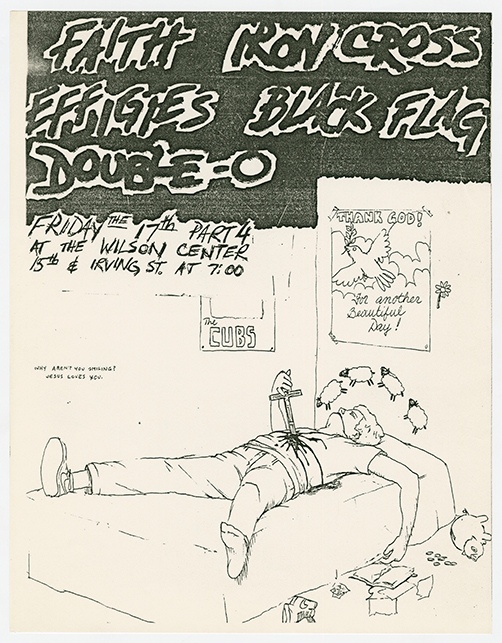

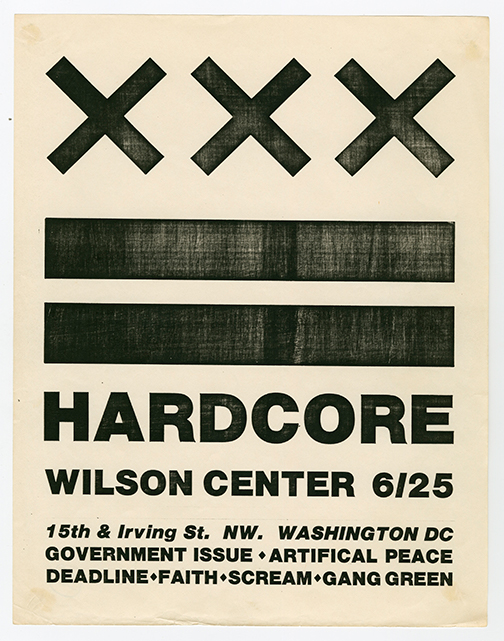

This year also saw the debut of some of the D.C. punk scene’s most lasting iconography. The work of designer Bob Raiter particularly stands out, as he collaborated with musician and concert promoter Malcolm Riviera on a series of memorable posters and design motifs. Raiter’s design for an April 30th show at the Wilson Center, consisting of an inverted cross composed of the words ‘D.C.’ and ‘HARDCORE,’ gave the scene an emblem that captured the confrontational, no-frills ethos at the heart of the community. Even more broadly identifiable was Raiter’s reimagining of the D.C. flag on a poster promoting a June 25th concert at the Wilson Center. Raiter’s design, employing three ‘X’s over two bars, would become a widely used and imitated reference to D.C. punk, particularly in the 21st century.4

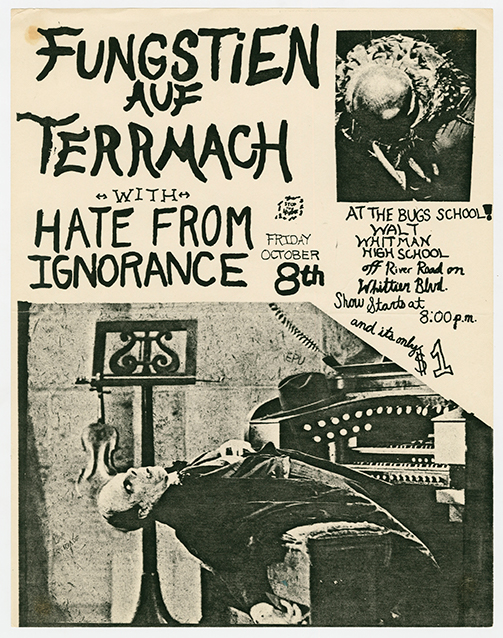

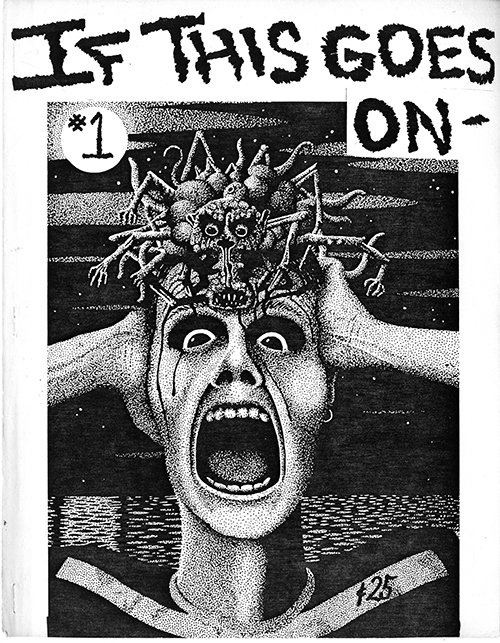

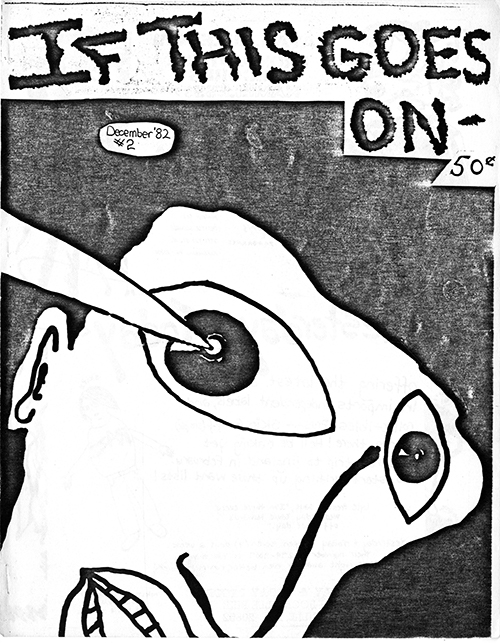

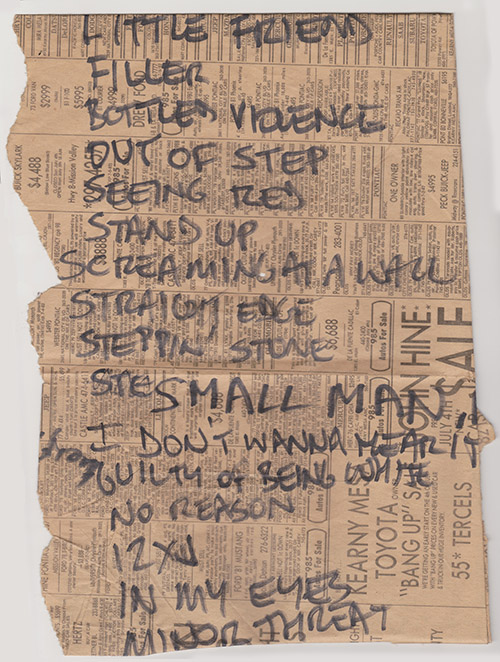

Despite these positive developments, cracks began to appear in the community’s facade. Punk clothing became increasingly uniform, stage-diving was routine, and the thrash style of hardcore that had so recently broken new ground grew stale. Eugene Bogan, bassist of Hate From Ignorance, described his frustrations with the sonic conformity: “I’m getting sick of D.C. stuff—or thrash. I think punk rock should get more musically oriented.”5 For others, the growing stagnation of the scene was more holistic, which Sharon Cheslow of Chalk Circle addressed in her fanzine, If This Goes On (co-edited with Colin Sears, later of Dag Nasty). Her review of the April 30th Wilson Center show—featuring Minor Threat, Artificial Peace, Faith, Iron Cross, Void, and Double-O—described the issue frankly: “Too many bands seemed content at playing tough (musically and physically) and there was a lot of the ‘we’re a D.C. band, we’re great’ attitude running among them.”6

Few bands in the D.C. scene, at the time or in the years to come, were more vocally at odds with their fellow punks than Psychodrama, who performed around the city a few times in 1982 before decamping for their next home in San Francisco. Psychodrama’s music and its performances were a cacophony of shrieks, clangs, and howls, realizing punk’s purported powers to shock and disgust with supreme efficiency. Vocalist Leslie Singer recalled that at the band’s first concert in February 1982 at St. Stephen’s Church in Washington, DC, “all ten people in the audience hate[d] us and walk[ed] out during the show.”7 The response from most of the DC punk scene remained disapproving, with the group earning bans from several venues and even, supposedly, “intervention and persecution of the group” from “vice squad detectives.”8

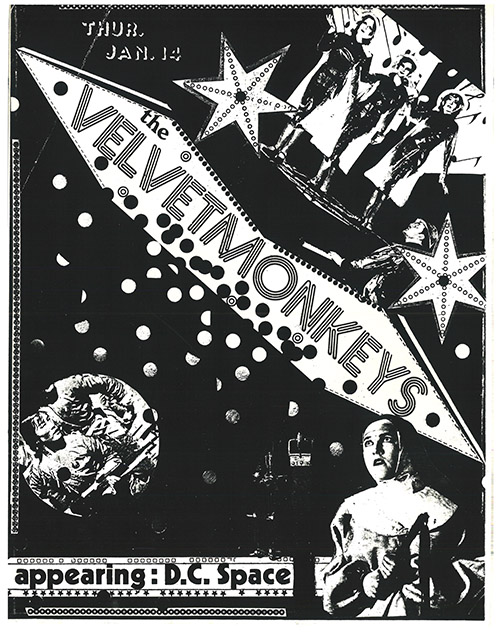

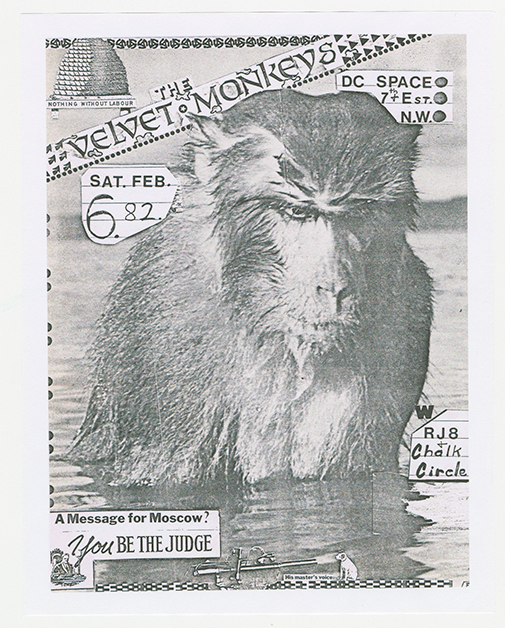

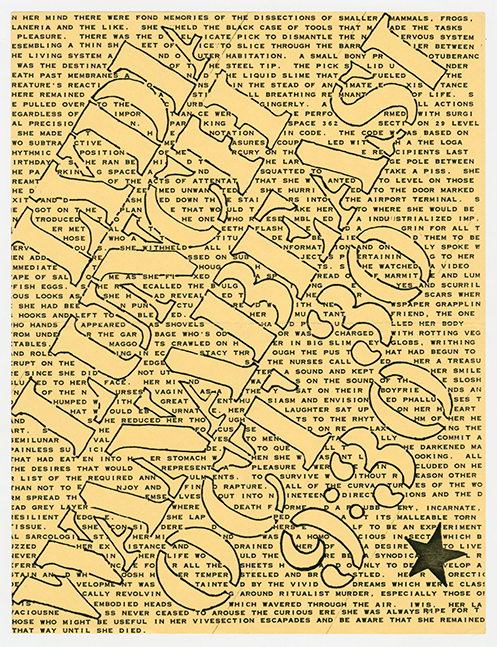

When Psychodrama published its own “fanzine” in April 1982, the contents within had little to do with fandom. The Alexandria Father Fucker, subtitled The Punishment Times, only lasted for two issues, but the band was still able to lay waste to their surroundings. The first issue featured a “nationwide music scene check-up” that dismissed most of the major American punk scenes like New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Boston with a one-word assessment: “Sucks.” DC gets skewered, as well. The Velvet Monkeys, a recent transplant to DC from Charlottesville, Virginia, “suck shit,” while the older DC punk bands “suck, naturally.” The zine took other scene participants to task, “Well, goddamn, it’s not our fault that everything sucks the way it does,” the introduction to the second issue read. “We are trying to improve things with this fanzine,” Singer wrote, “so, if all you’re doing is hanging out down at [the] 9:30 [Club] and buying records in Georgetown and at RTX9, don’t say a fucking word to us, ‘cause you’re not doing jack shit.” Singer later admitted that “the zine does come off as being very bitter.” Reflecting on the hostile tone of The Alexandria Father Fucker, she wondered “if Brett [Kerby, also of Psychodrama] and I were also adopting the pose and mouthing the story line that other bands in D.C. had at that time: D.C. sucks, it's so conservative, blah, blah, blah.”10

Aside from gripes about creative stasis within the scene, Minor Threat’s explosive popularity became another source of friction to be hashed out in D.C. punk fanzine articles and post-concert kaffeeklatsches at late-night spots around town like the Tastee Diner, Hot Shoppes, and Montgomery Donuts. The group disbanded briefly in late 1981 before reuniting in early 1982. During their hiatus, Minor Threat’s music spread throughout the world and interest in the band reached a pitch that no other D.C. group had yet achieved. Fanzine coverage of the D.C. scene often discussed Minor Threat’s new stature, with some writers and bands glad to see the group reform. To others, however, Minor Threat had gone flat creatively and their large fan base—including countless newcomers, often from further out in the D.C. suburbs—strained the closeness of the community. As Cheslow continued in her review of the April 30th show, she was disappointed that so many there had missed that night’s set by the Faith: “Why did people leave? Because Minor Threat had played before them, and once they had played, people weren’t interested in any other bands. So much for D.C. unity.”

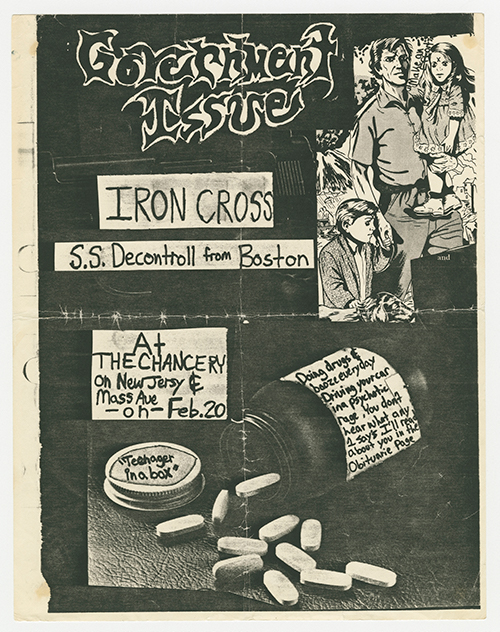

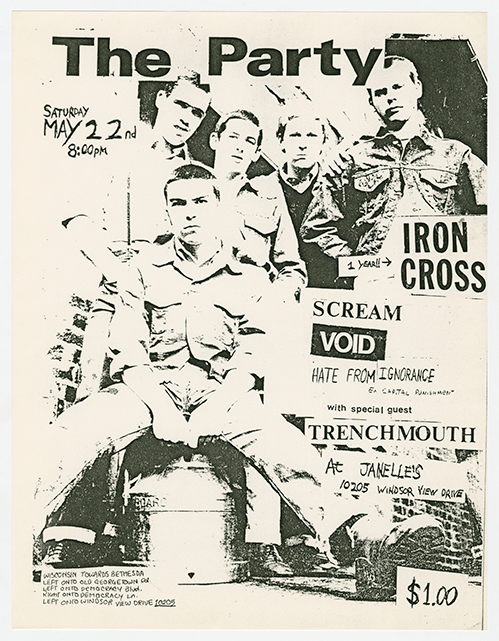

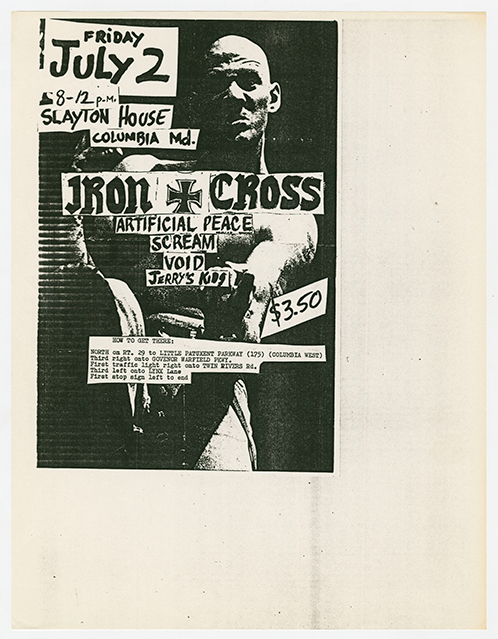

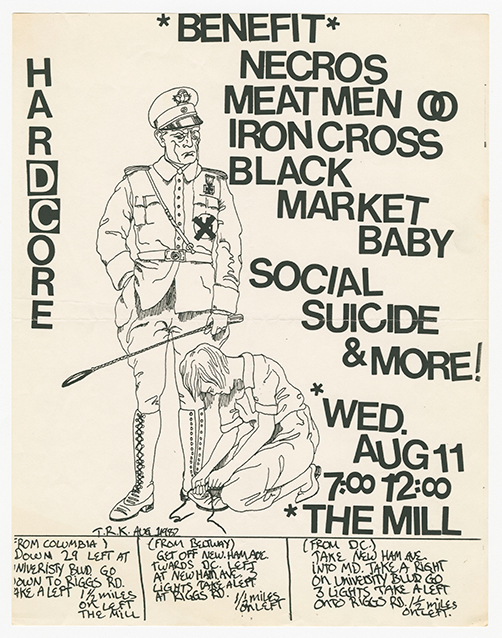

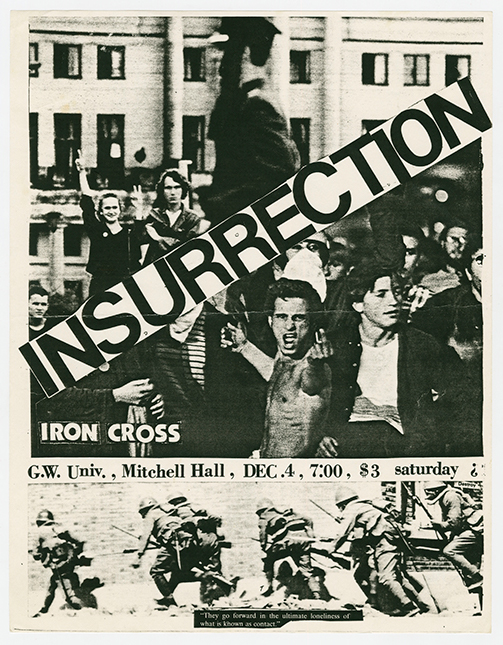

Cheslow also used If This Goes On as a forum to confront another problem in the scene when she interviewed the D.C. punk band Iron Cross, challenging them about their controversial behavior. As author and filmmaker Steven Blush later wrote, despite breaking ground as one of the first American bands to employ the Oi!11 style of punk popular in the United Kingdom, “many in D.C. laughed off Iron Cross as quasi-nazi [sic] buffoons”12 due to the band’s name—a German military decoration with a long history, but its ties to Nazi Germany were glaring—and lyrics that were called out for being homophobic and glorifying of violence, such as in the songs “Psycho Skin” and “Fight ‘Em All.”13 The group had also made ignorant comments about racism in an interview with Touch and Go fanzine14, while vocalist Sab Grey’s fanzine Skin Flint included some homophobic and racist humor.

Iron Cross dismissed much of the criticism, saying that most of the real-life violence involving band members was in self-defense and that their sense of humor was just irreverent and misunderstood. After drummer Dante Ferrando lamented in the If This Goes On interview that the band gets “shit on” despite trying to support others in the scene, Cheslow countered that the criticisms were “because of your image and instances like at the Wilson Center when you were sieg heiling Government Issue.” Grey rationalized that it was “a personal joke between us” and Government Issue vocalist John Stabb. “We were going ‘[Stabb] is a homo’” while sieg heiling, Grey explained, seemingly oblivious as to why these actions would reasonably offend most people. “We have never been Nazis,” he insisted. “We may joke about it, but everybody else does, too.”

In a June 1982 interview with the San Francisco punk fanzine Maximum Rocknroll, Minor Threat was outspoken in their criticism of Iron Cross. After Minor Threat bassist Brian Baker and guitarist Lyle Preslar scoffed at Grey’s insistence that the name Iron Cross was not meant to evoke Nazi Germany, vocalist Ian MacKaye censured the band in explicit terms: “They claim not to be racist or Nazis but, on the other hand, there are quite a bit of overtones involved, as well as ignorance.”6 MacKaye backtracked from those comments in an apologetic letter that ran in Maximum Rocknroll’s following issue, but others questioned the band’s values, as well. Tim Yohannan’s review of Iron Cross’ 1982 EP Skinhead Glory in Maximum Rocknroll took aim at “Psycho Skin,” a song written from the first person perspective of a drunken criminal who engages in homophobic violence. Unnerved by the ambiguity of “Psycho Skin”’s first person narrative, Yohannan asserted that “when dealing with sensitive subject matter, it would be helpful if bands included more information on what it is they’re trying to say. After all, isn't the object of music to communicate feelings and ideas?”15 Grey was subsequently more vocal in his attempts to convince people that Iron Cross did not genuinely hold racist or homophobic views. Interviewed later in 1983, Grey rejected homophobic and misogynistic violence, asserting if “you abuse someone for being who they are, be it gay, woman, punk, or redneck, then you’ve lost your rights as a human being.”16 Grey also denounced some of the newer, openly racist skinheads in the DC scene from the stage at a September 1984 concert, angered that his band was viewed as an inspiration for people he thought of as fascists.17

Reflecting on this period decades later, Grey observed that “part of being young, of course, is reveling in seeing your elders squirm, so taking delight in being extreme can become the norm and sort of a badge of honor. The word they use now would be ‘edgelord,’ but a better description would be ‘loudmouth prick.’”18 Ferrando, too, later cited the band’s immaturity as the root of their misbehavior. “To some degree, if we were older, it probably should have given us reservations [to name the band] Iron Cross or [to make] jokes in poor taste or [be] anywhere near as belligerent as we were about some things,” he said in a 2006 interview. “But you’ve got to remember, I was thirteen when I joined the band. The oldest member of the band was seventeen, eighteen. We were young kids. We were really into pissing people off. We didn’t really like anybody, at all. There definitely wasn’t an agenda—racist [or] sexist.”19

Much as in greater D.C. itself, progress within the punk scene was entwined with setbacks. Tensions rose and change was afoot, both welcome and otherwise. The rapidly expanding D.C. hardcore scene had already exceeded its earlier incarnation of a few overlapping groups of friends intersecting at punk shows, record stores, and neighborhood haunts. By the end of 1982, as more fans came out to concerts, more bands formed to take part in the scene, and more fanzines were published to chronicle it all, the degree of expansion and increased scrutiny that the D.C. scene experienced would soon push the growing community to a crucible point.

Further Listening

Bad Brains. Bad Brains. ROIR, Album.

The Faith and Void. Faith/Void Dischord Records, split LP.

Tommy Keene. Strange Alliance. Avenue Records, Album.

Psychodrama. 300 Days of Sodom (The Vomit of Psychodrama). Self-released, Album.

Static Disruptors. DC Groove. Wasp Records, 7-inch single.

Tru Fax and the Insaniacs. Mental Decay. Wasp Records, Album.

Various. Flex Your Head. Dischord Records, Compilation album.

Velvet Monkeys. Everything is Right. Big Circus, Album.

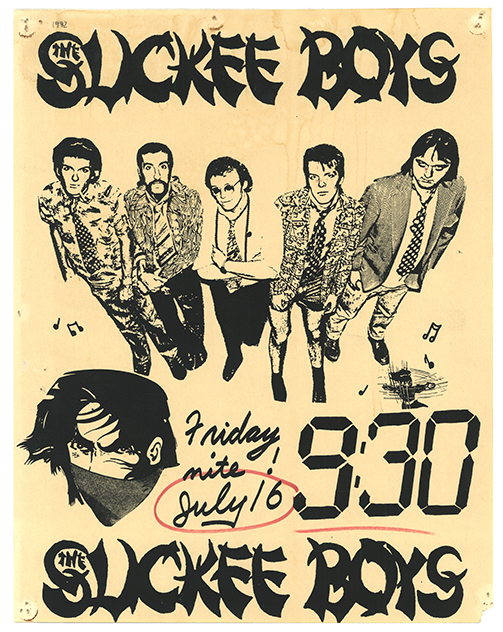

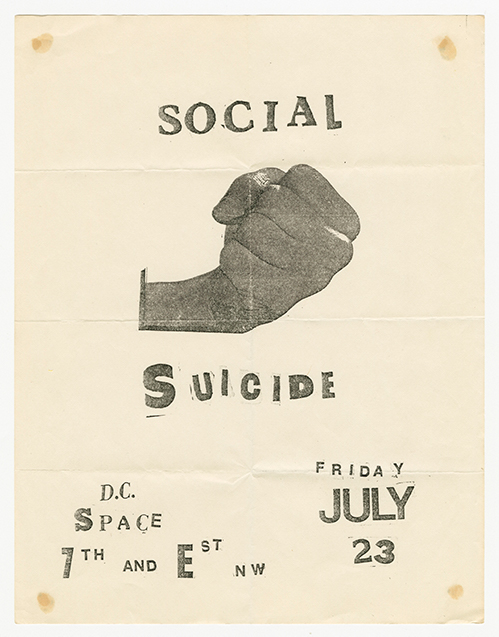

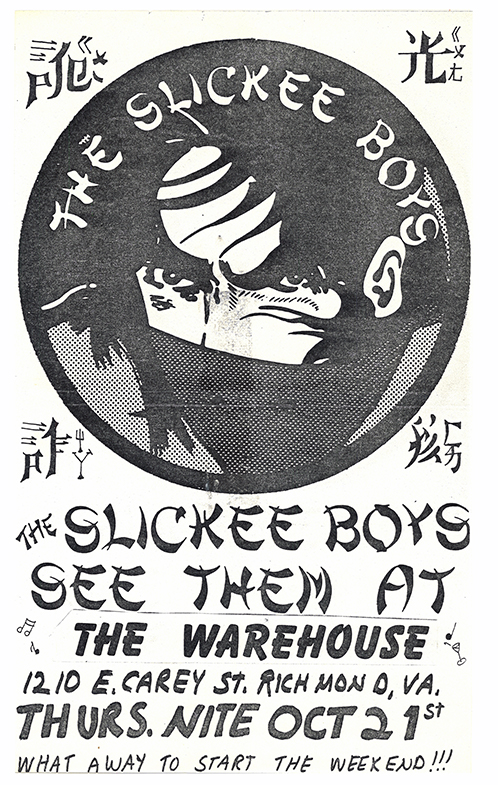

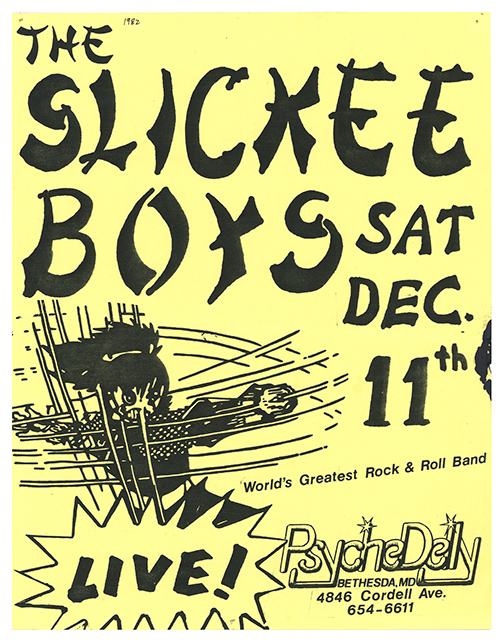

Materials are drawn from the Chris Baronner digital collection on D.C. punk, the Paul Bushmiller collection on punk, the Sharon Cheslow punk flyers collection, the D.C. punk collection, the D.C. punk and indie fanzine collection, the Kevin Salk collection of D.C. punk photography, and the Robbie White collection on the Slickee Boys.

Tap or hover over an image to learn more.