The “Revolution Summer” movement in the D.C. punk scene of 1985 is often thought of as a rebirth of the community, a return to a more inclusive, less violent scene that prized creativity over conformity and activism over apathy. However, the woman who coined the term “Revolution Summer”—musician and Dischord Records employee Amy Pickering—did not think of that period as a new beginning: “Revolution Summer was the climax, it was the end of something.” 1

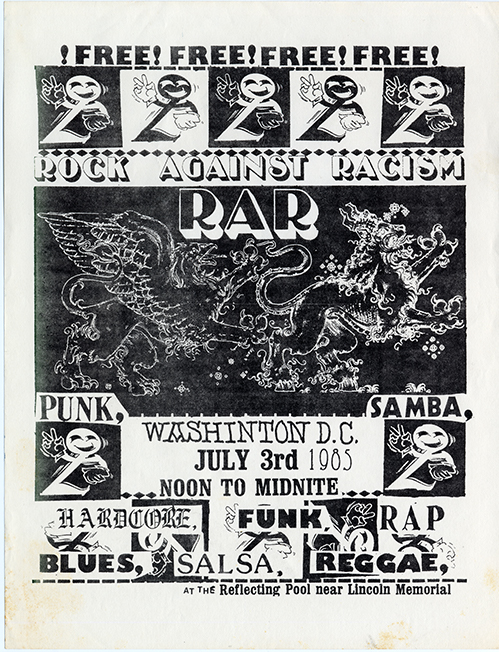

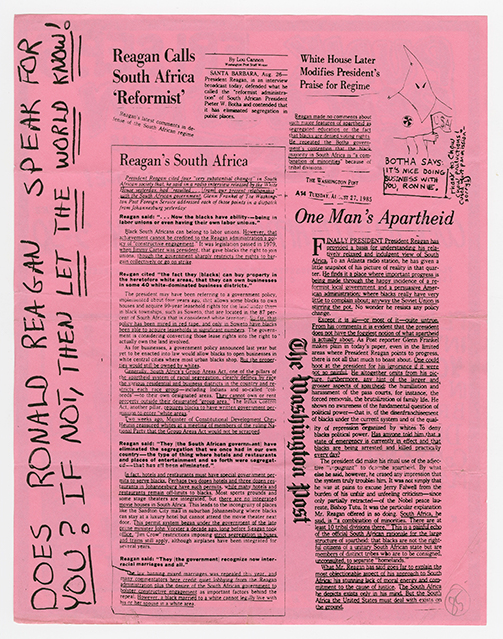

Between tasks at her part-time job at a Neighborhood Planning Council office in D.C., Pickering included the term “Revolution Summer” on anonymous notes she circulated to fellow punks in the community, along with critiques of the violence in the scene and the disconnect between D.C. punk and broader issues of the world.2, 3 With the advent of the Reagan Doctrine—a strategy seeking to reduce global Soviet influence—along with the ascendency of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and the sharp increase in apartheid political violence in South Africa, D.C.’s Revolution Summer of 1985 saw members of the punk community join a global political moment of protest. From the administration’s continued inaction on Apartheid violence to Reagan’s own unintentional laying of a wreath at a graveyard that held the remains of Nazi soldiers, America was marked by indifference alongside growing conflict, in part fueled by the inflammatory rhetoric of the Reagan Doctrine. Activism grew throughout the United States, leading to the administration changing course in September via an executive order that reversed Reagan’s opposition to economic sanctions against South Africa. Turmoil in the District’s government continued through the year, culminating in the guilty plea of former Deputy Mayor Ivanhoe Donaldson, who was convicted on charges of stealing $190,000 from the city.4

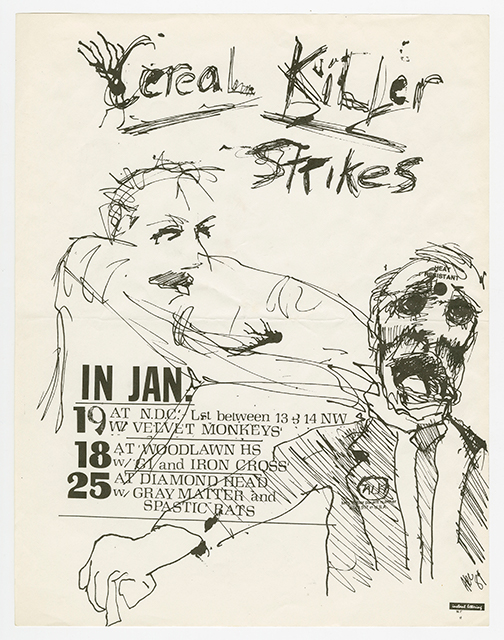

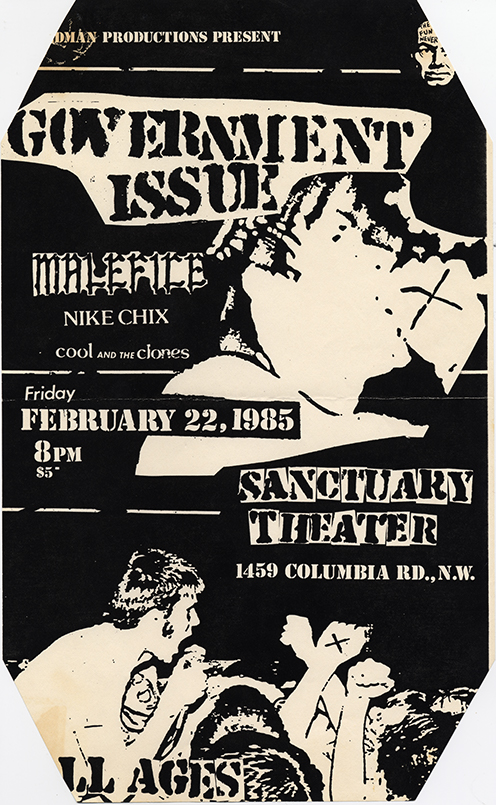

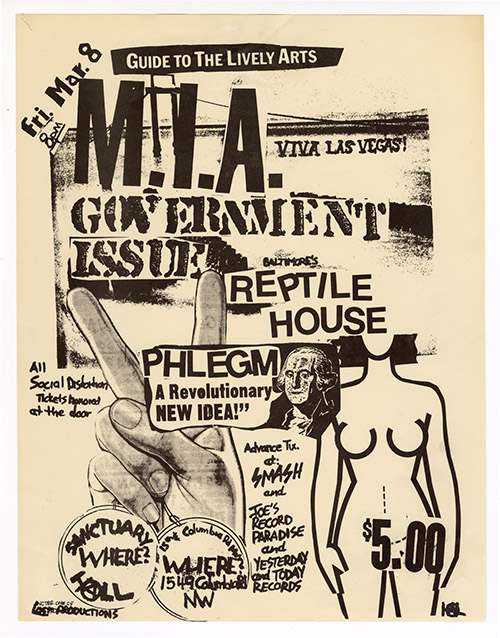

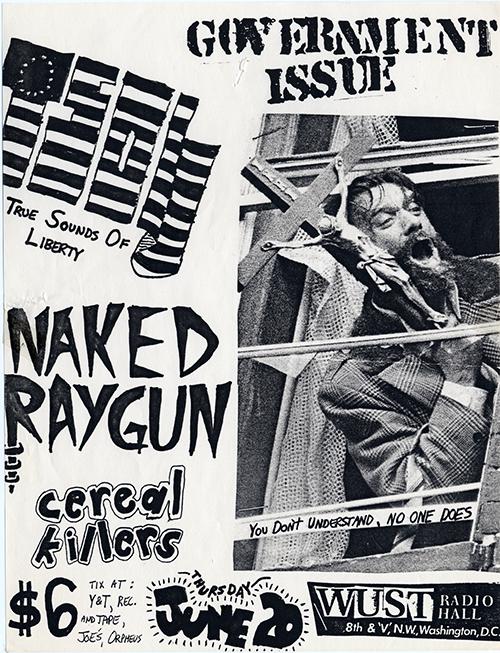

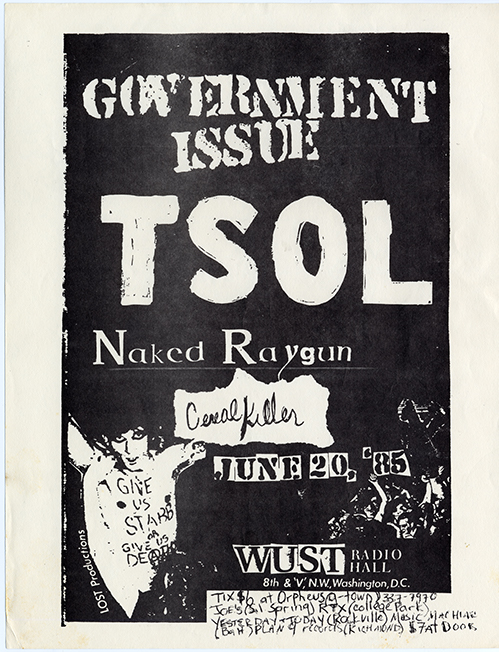

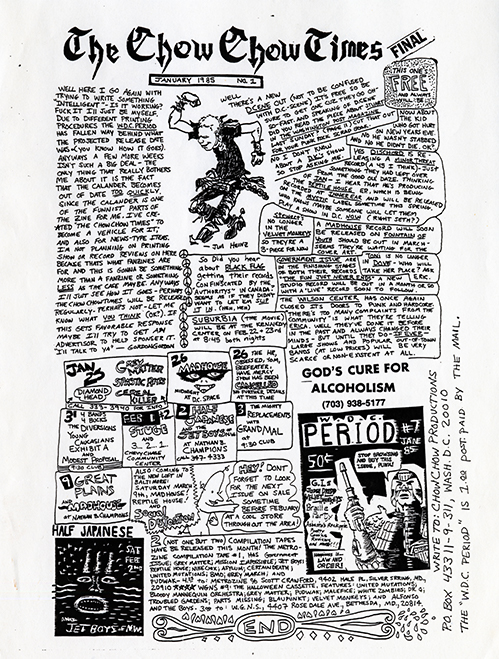

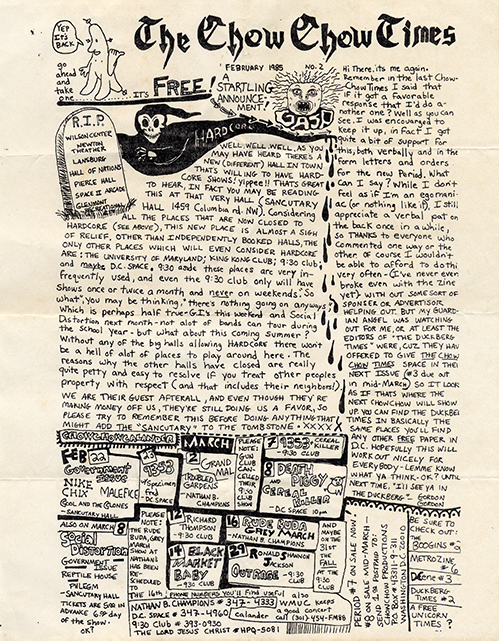

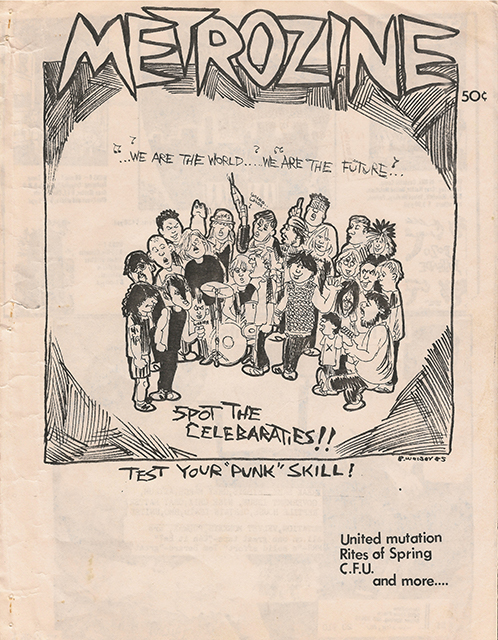

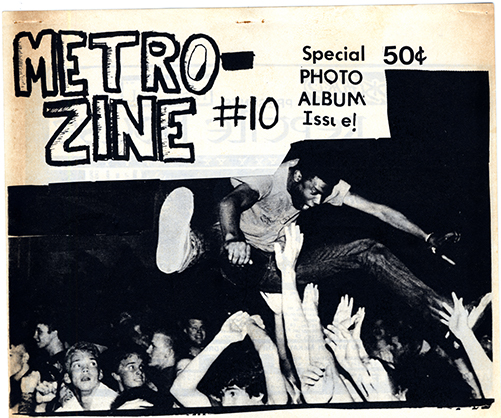

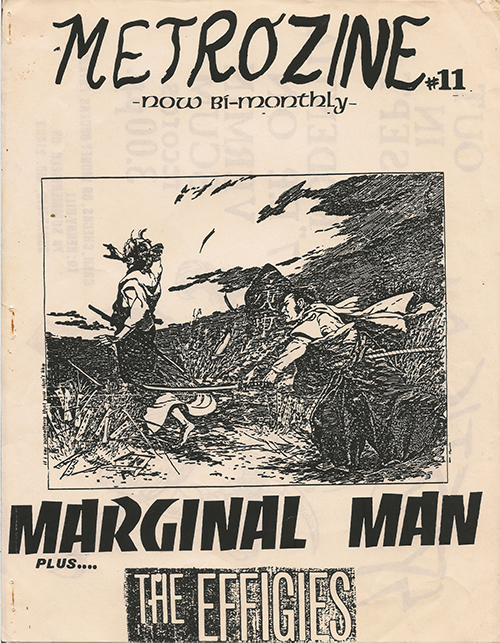

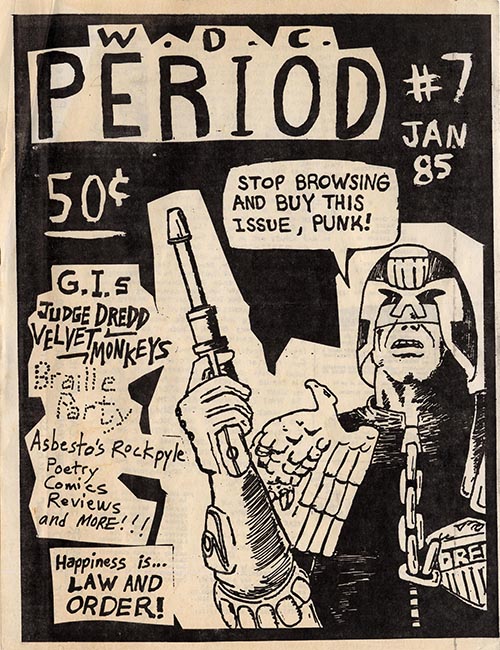

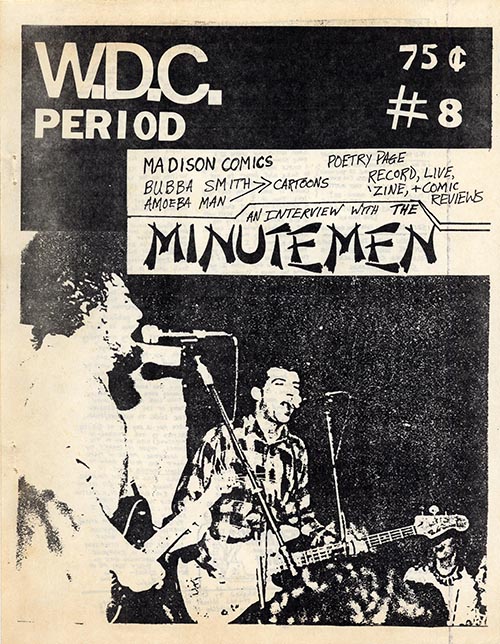

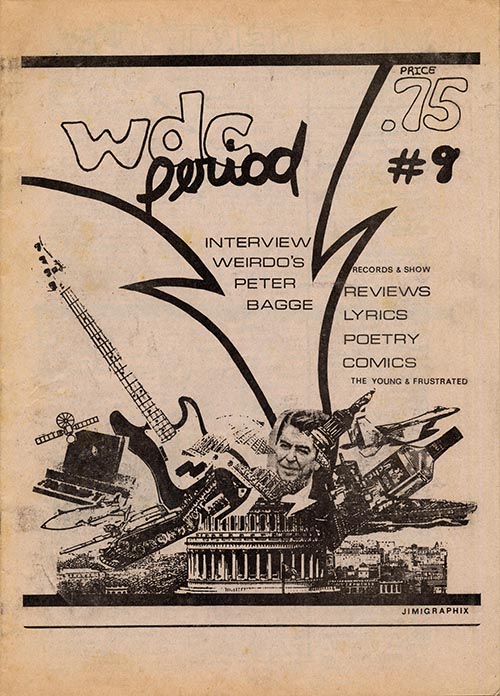

Against the backdrop of this political unrest, the D.C. scene responded in 1985 with its own radical remaking, true to the frequent reinvention that had permeated the scene from its onset. However, at the year’s beginning, the explosion of activity to come that summer was by no means a sure thing. An editorial by John Stabb of Government Issue, “Blow Out the Candles, D.C.,” appeared in the opening pages of Metrozine issue seven, in which Stabb appeared weary at the state of the scene and its increasing violence, asking “do you want a football game or a show?”5 Similarly, the second issue of Gordon Ornelas’ Chow Chow Times from February 1985 opened with the spectre of death wearing a robe scrawled with the word “hardcore,” as it extended a skeletal hand towards a tombstone engraved with the names of venues that had seemingly become hostile to the scene or had shuttered.6

...

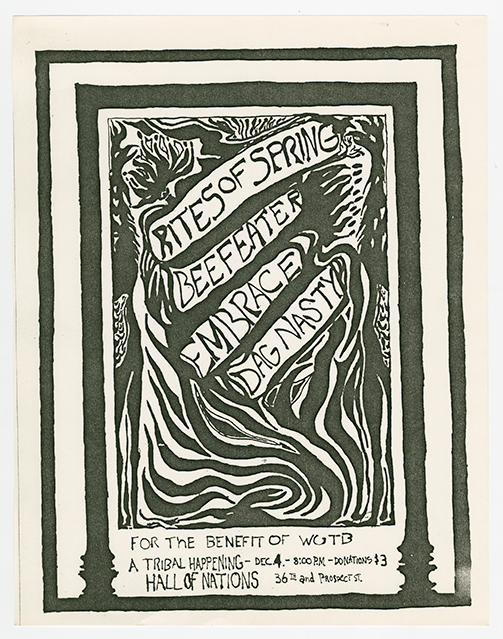

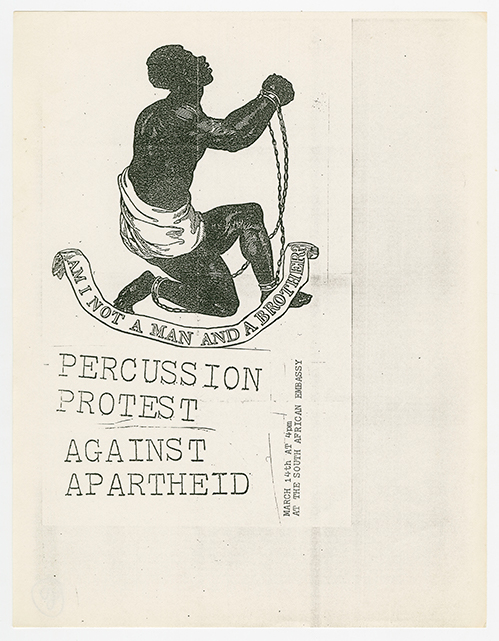

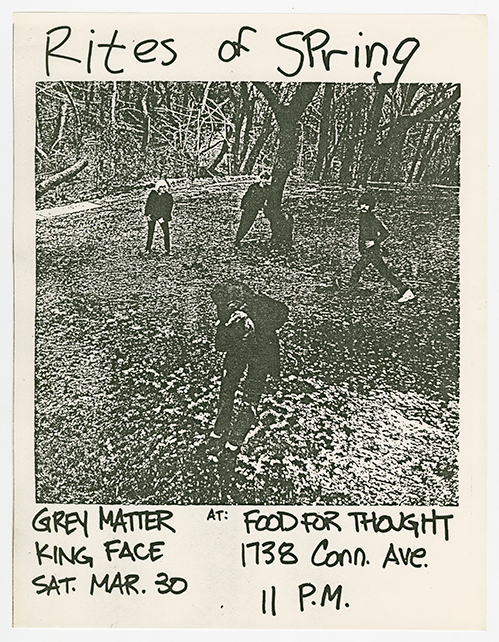

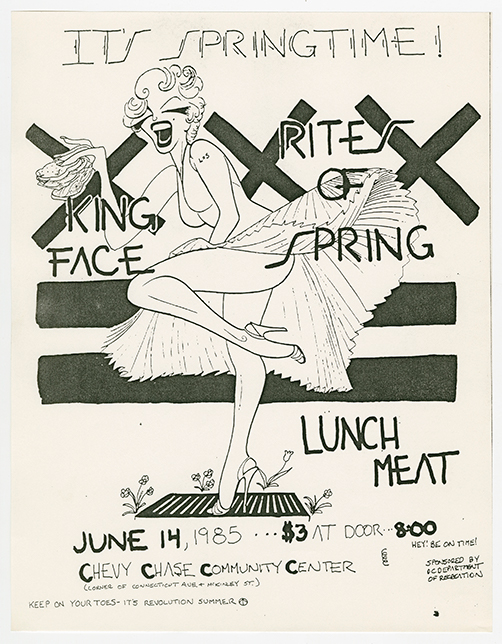

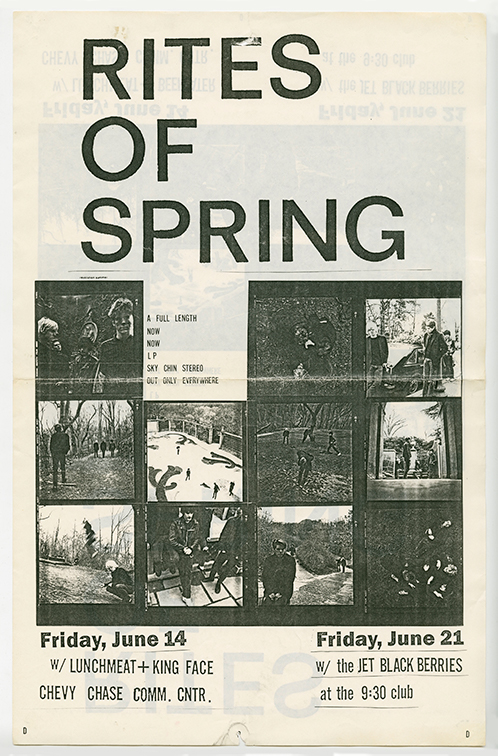

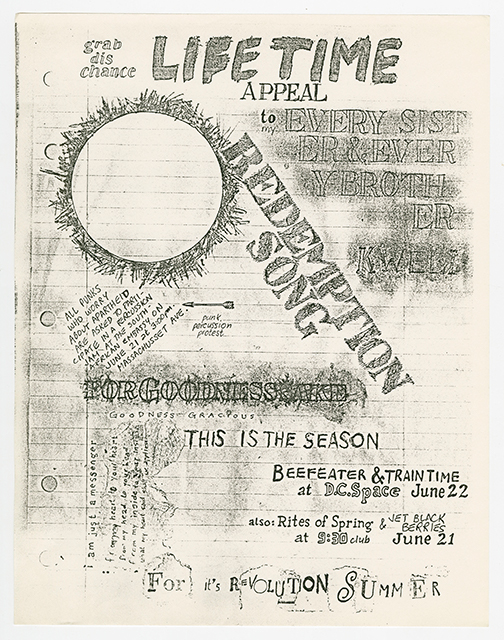

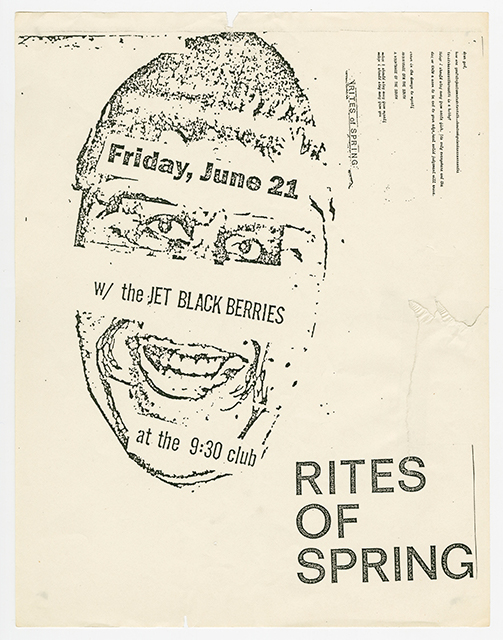

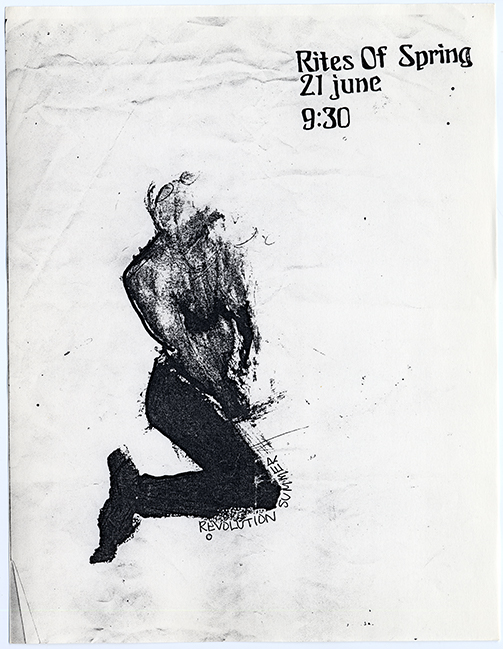

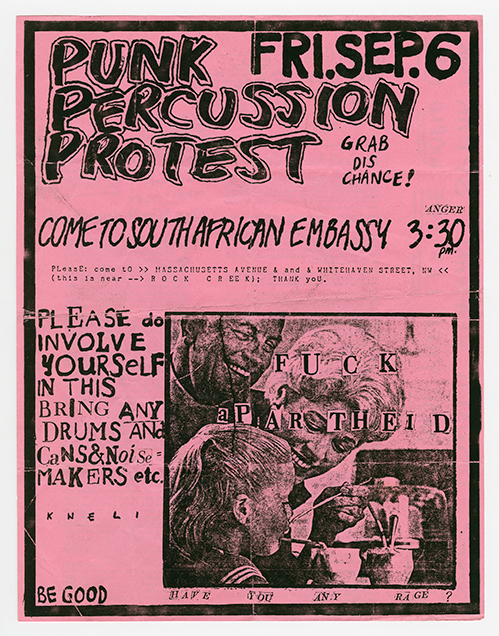

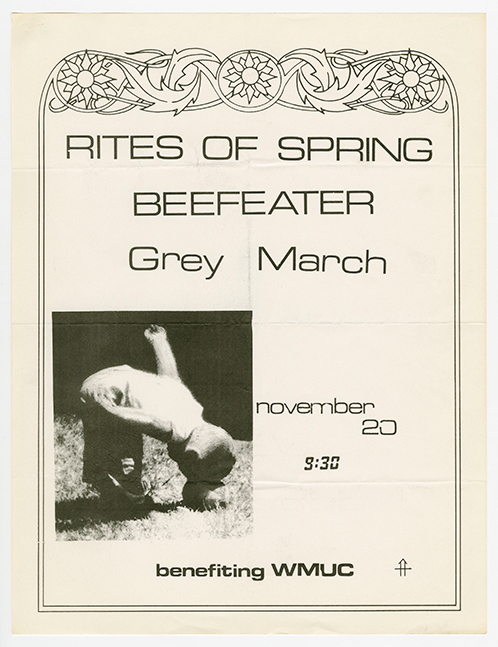

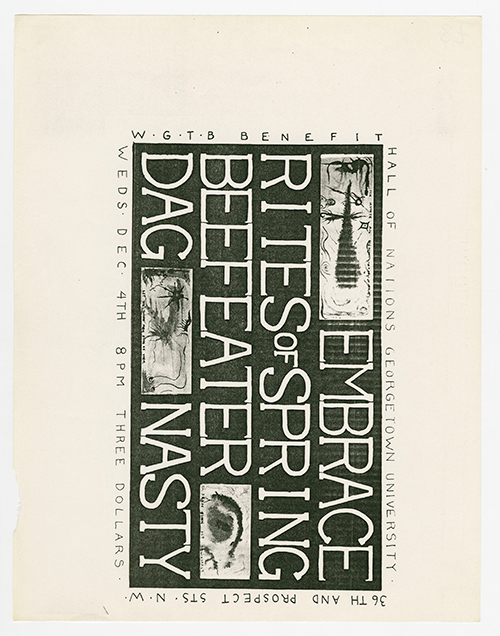

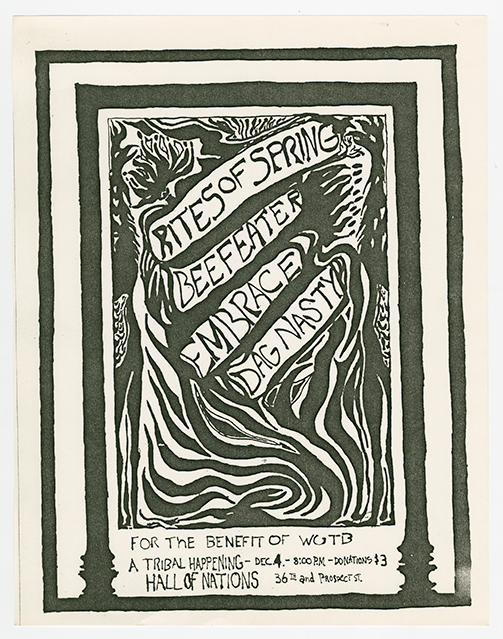

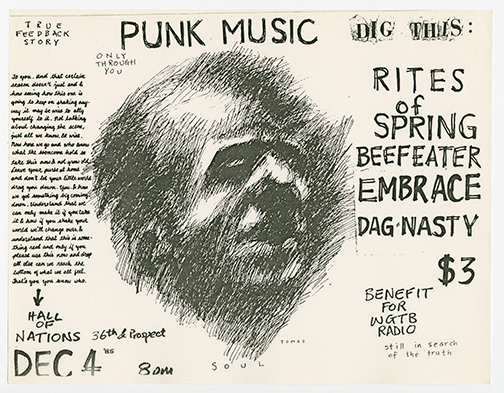

Revolution Summer was a spark of rejuvenation that marked a new era in the political consciousness of the scene with the Punk Percussion Protest against Apartheid on June 21st of the year. Originally born out of Chris Bald’s suggestion that Beefeater perform “Apartheid No” at the South African Embassy, the protest was announced at a preceding Rites of Spring performance.7 Members of Rites of Spring, Beefeater, Gray Matter, and others in the scene joined with drums and other forms of percussion to make noise in the first of more anti-apartheid protests to come. One flier for the event, designed by Tomas Squip speaks to how this protest was a natural extension of the longstanding DIY ethos to the material conditions asking simply in cut-out letters: ”PLEASE do INVOLVE YOURSELF IN THIS BRING ANY DRUMS ANd CaNS & Noise MAKERS etc. FUCK aPARTHEID.” Along with the protest, the formation of Positive Force D.C., a punk activist collective responsible for the explosion of protests, benefit shows, and tabling that followed the summer of 1985 marked a shift in the scene towards punk as a means to pursue justice locally and globally.8

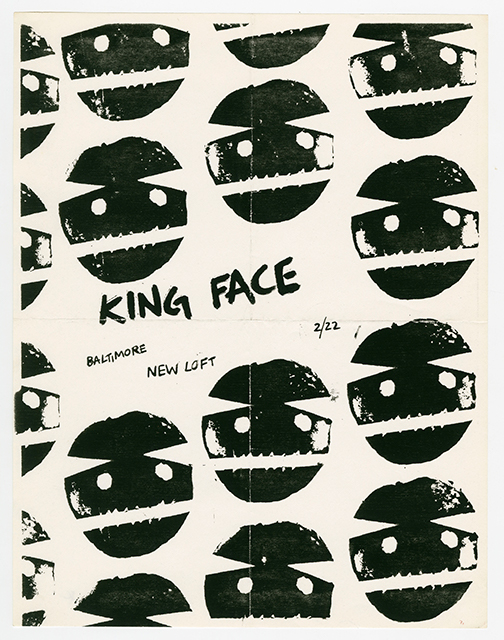

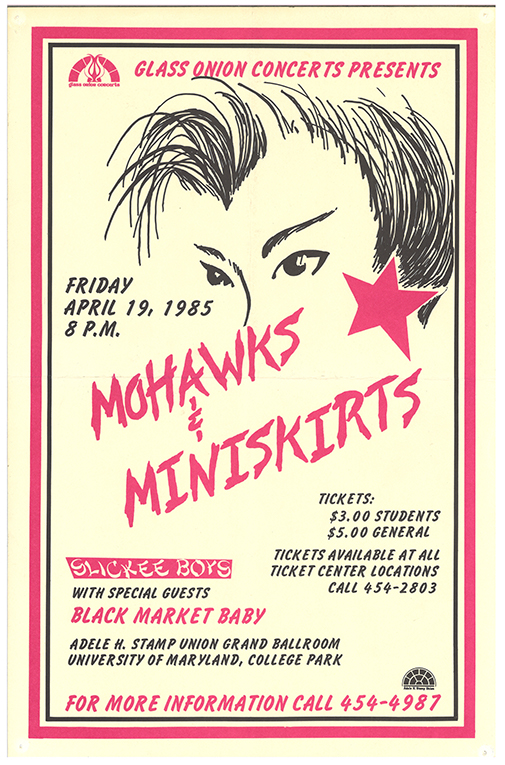

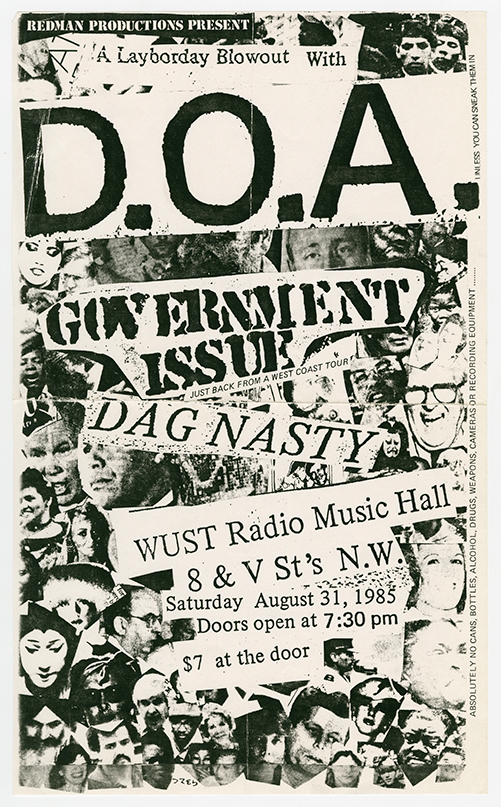

Many of the defining acts of the hardcore era such as Minor Threat, the Faith, Void, and State of Alert were now broken up. The high-velocity blast beat sound from the beginning of the decade was falling out of favor, with bands like Marginal Man, Gray Matter, Beefeater, Rites of Spring, and King Face pushing the scene into a new direction while still drawing connections to the past. Dag Nasty was formed by guitarist Brian Baker of Minor Threat, drummer Colin Sears and bassist Roger Marbury of Bloody Mannequin Orchestra, and vocalist Shawn Brown.9 The band’s crisp and ferocious performances evoked the fire of the early hardcore scene but were wholly resonant with the present moment. Dag Nasty was also notable for being one of the relatively few punk acts in the city in this part of the decade that were fronted by a person of color. When the band went onto record their debut album the following year, however, Brown was ousted in favor of Dave Smalley because as Brown later put it, “the band was looking for a more melodic approach” rather than Brown’s stentorian snap. Brown would soon return, however, with a new band, Swiz.10

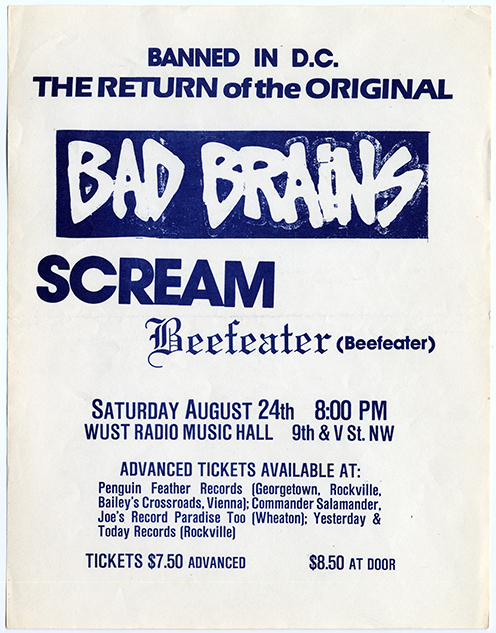

Dischord’s releases from 1985 highlight the ways in which artists pushed back against the increasingly meaningless and rigid interpretations of what qualified as punk. Beefeater’s Plays for Lovers blended breakneck tempos and sharp guitars with slapped bass on tracks like “Trash Funk.” Scream—made up at this point of Robert Lee Davidson, Peter Stahl, Franz Stahl, Kent Stax, and Skeeter Thompson—released Still Screaming which also displayed the increasingly malleable sound of the city. Scream moved fluidly from the blistering “Things to Do Today” to the album’s title track, weaving in elements of dub and ska. In a similar manner, the opening two tracks of Gray Matter’s Food for Thought LP serve as a further representation of the scene’s musical flexibility, moving from the propulsive, post-hardcore sound on the opener “Retrospect” to the fluctuating tempos and tenors found on the second track, “Oscar’s Eye.”

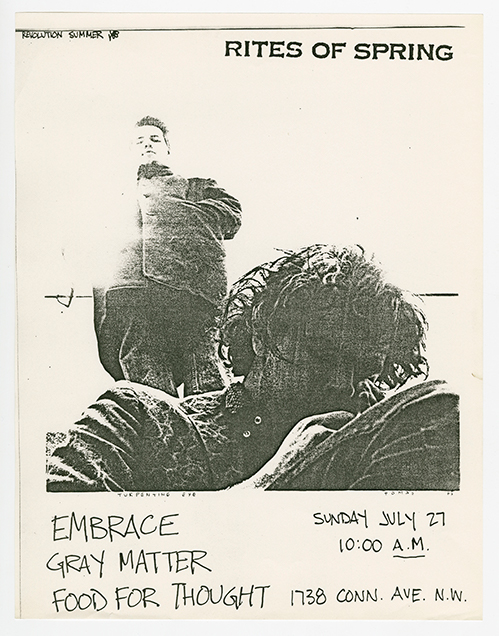

After recording a demo and playing initial shows in 1984, Rites of Spring became a staple of the scene in 1985 and were emblematic of the shifting current of the community. The band’s eponymous LP, featuring songs like “End on End,” “For Want of,” and “Persistent Vision,” was released in 1985. The compositions are striking for their introspective lyrics, which unabashedly reflect on change, one’s relationship to others, and one’s relationship to oneself. The raw, combustible nature of the group was a key part of Rites of Spring’s essence. “We barely made those albums,” drummer Brendan Canty recalled. “We just decided, ‘Let’s get into a room and record these songs before our guitars break.’ Which eventually they did.”11

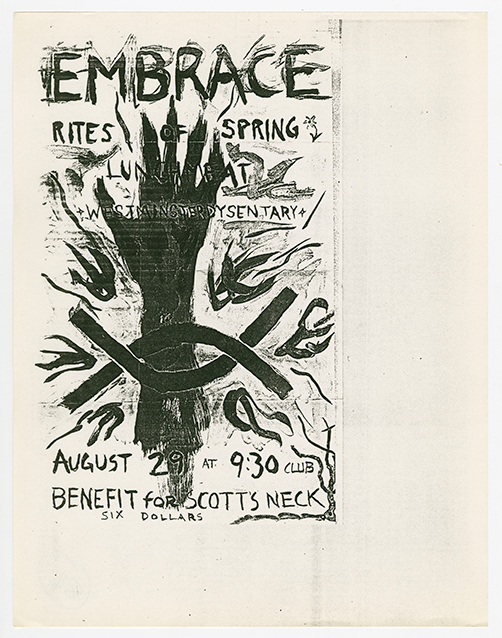

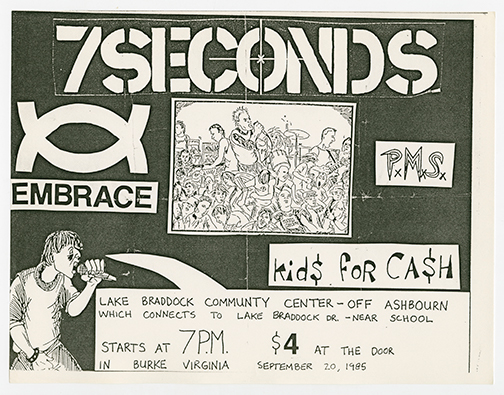

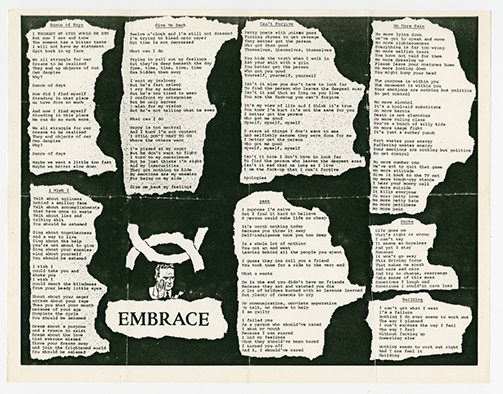

Embrace, which began performing in 1985, similarly turned the focus of its music to personal struggle and pain. Ian MacKaye’s vocals moved between his withering scream of the Minor Threat-era to anthemic singing or down to a whisper.12 This, paired with the wide harmonic palate heard in songs like “Dance of Days” and the more exploratory dimensions brought by bassist Chris Bald, guitarist Michael Hampton, and drummer Ivor Hanson—all former members of the Faith—made Embrace, like Rites of Spring, the defining sound of 1985 and a window into what was to come.

By the year’s end, Revolution Summer had created a sense of revival and remaking in the scene. The explosion of the summer months served as a reminder that the scene’s continued vitality was a direct result of its refusal to remain static, and its capacity to be redefined without losing sight of what came before.

Further Listening

Beefeater. Plays for Lovers. Dischord Records, Album.

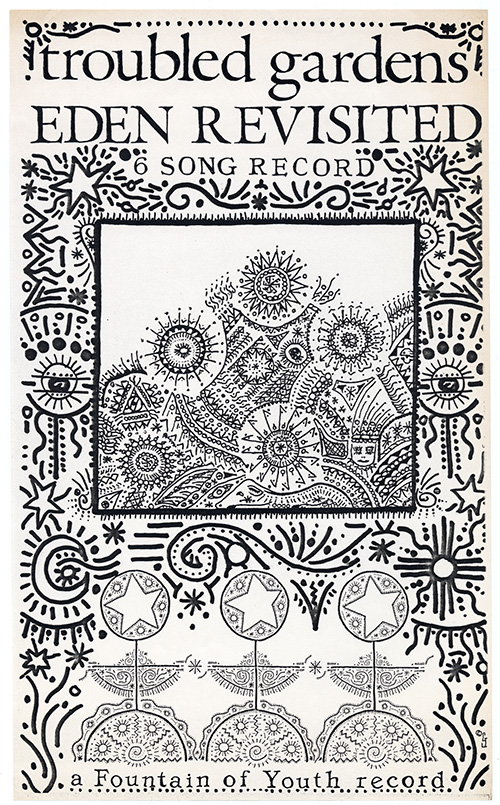

Government Issue. The Fun Just Never Ends. Fountain of Youth Records, Album.

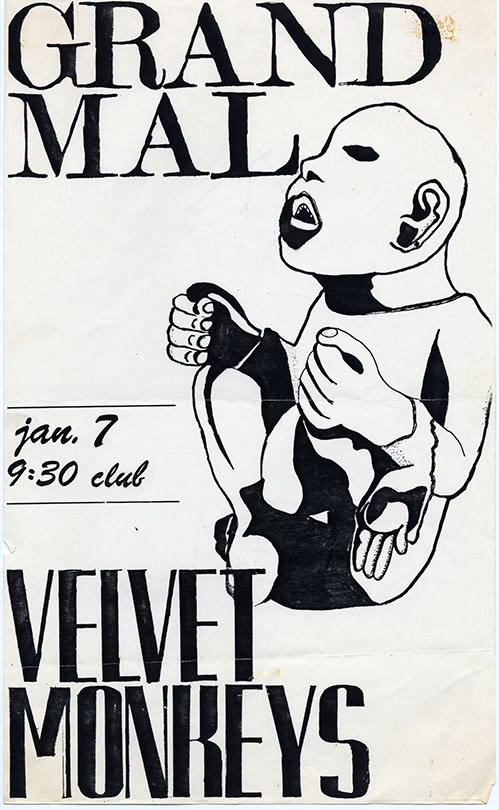

Grand Mal. Binge Purge. Fountain of Youth Records, Album.

Gray Matter. Food for Thought. R&B Records/Dischord Records, Album.

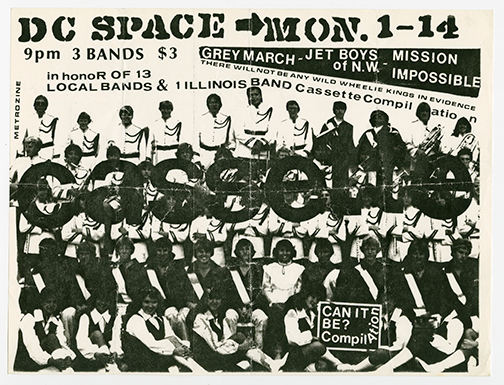

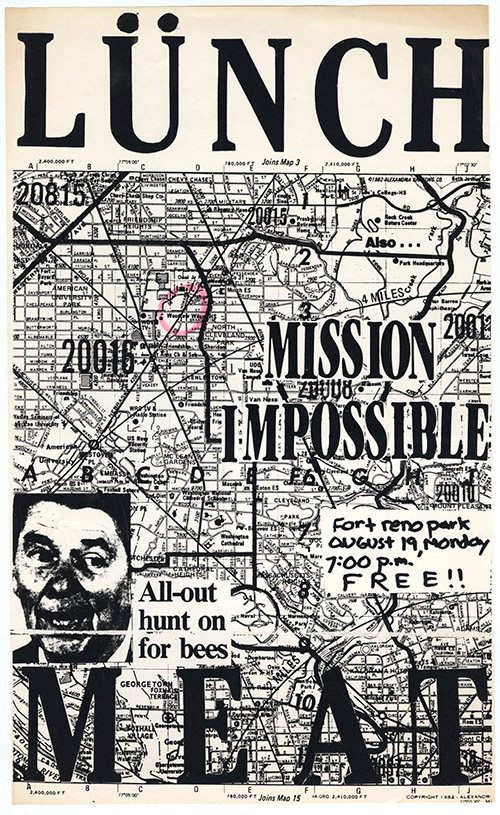

Lünch Meat / Mission Impossible. Thanks. Dischord Records/Sammich Records, split 7-inch EP.

Madhouse. Madhouse. Fountain of Youth Records, Album.

Marginal Man. Double Image. Gasatanka/Enigma Records, Album.

Minor Threat. Salad Days. Dischord Records, 7-inch EP.

Peach of Immortality. Talking Heads ‘77. Adult Contemporary Records, Album.

Pussy Galore. Feel Good About Your Body. Shove Records, 7-inch EP.

Rites of Spring. Rites of Spring. Dischord Records, Album.

Scream. This Side Up. Dischord Records, Album.

The Snakes. I Won’t Love You ‘Til You’re More Like Me. Discard (Dischord) Records, Album.

United Mutation. Rainbow Person. DSI Records, 7-inch EP.

Unrest. Unrest. Teenbeat Records, 7-inch EP.

Uruku. Exhumed Lunch. DSI Records/Scrapple Bath, 7-inch EP.

Various. Alive and Kicking. WGNS Recordings/MetroZine, 7-inch compilation EP.

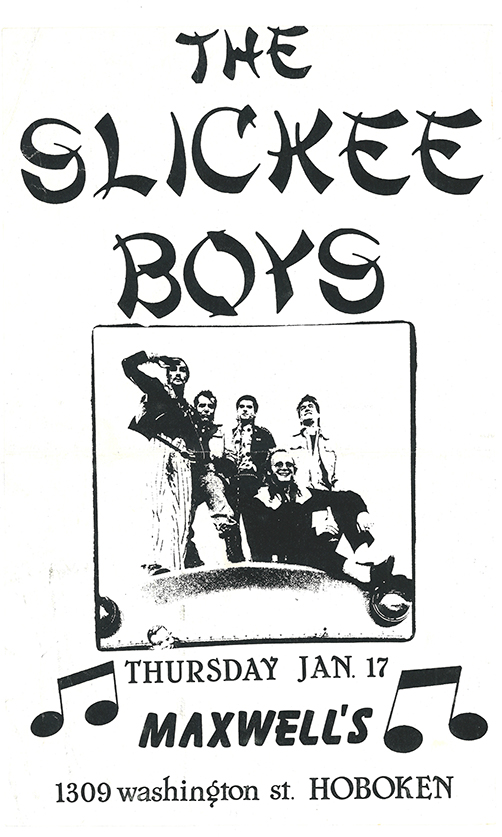

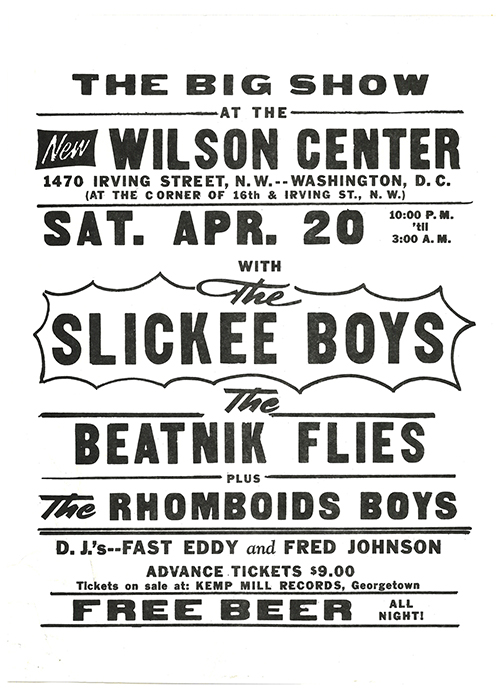

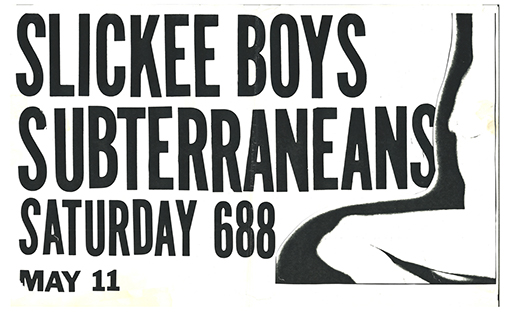

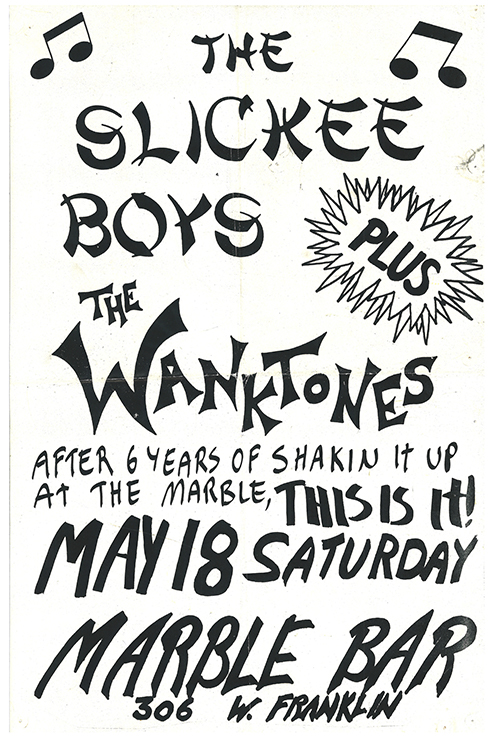

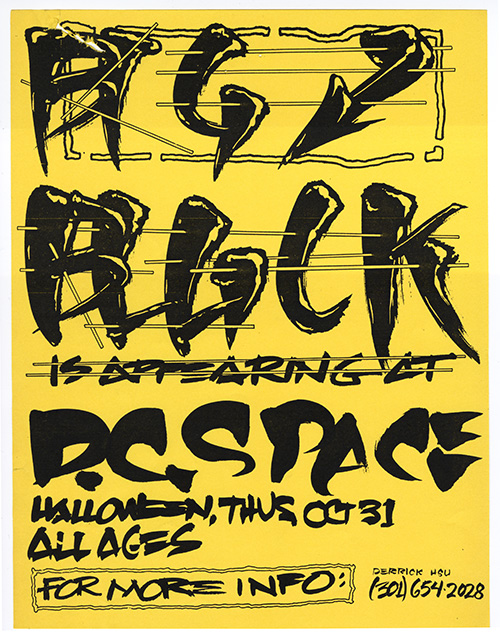

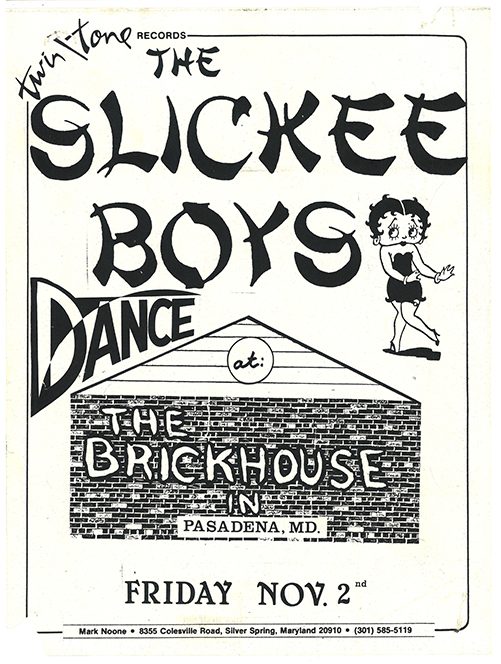

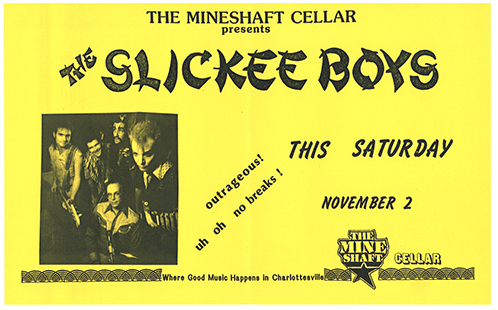

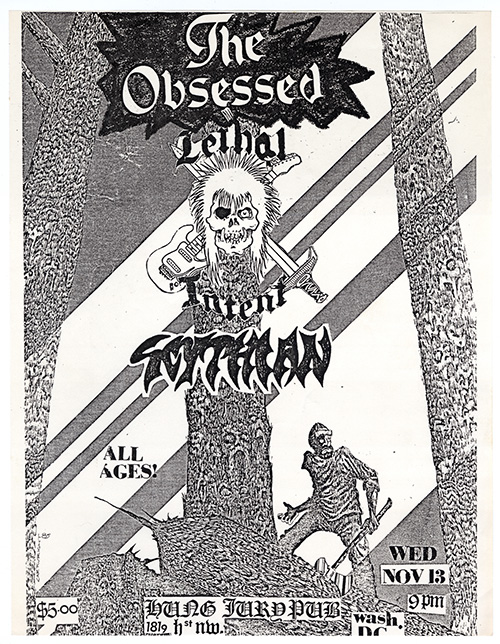

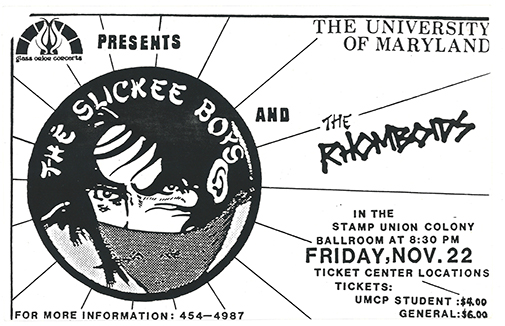

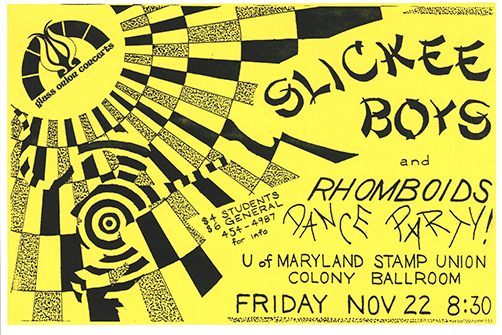

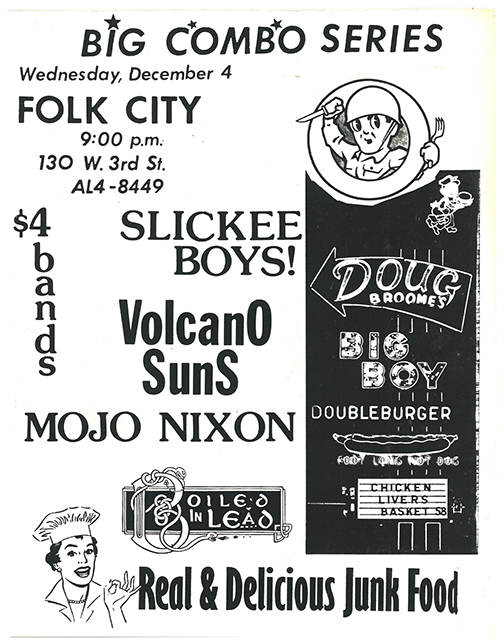

Materials are drawn from the Paul Bushmiller collection on punk, the Sharon Cheslow punk flyers collection, the D.C. punk and indie fanzine collection, the Skip Groff papers, and the Robbie White collection on the Slickee Boys.

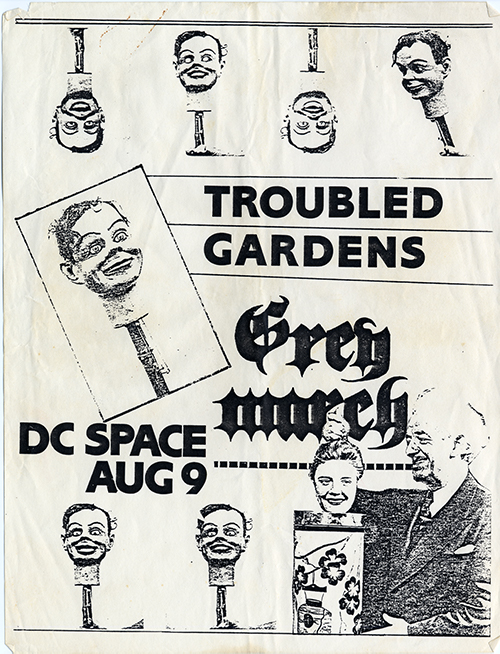

Tap or hover over an image to learn more.

FLIERS

ZINES

EPHEMERA

RECORDINGS

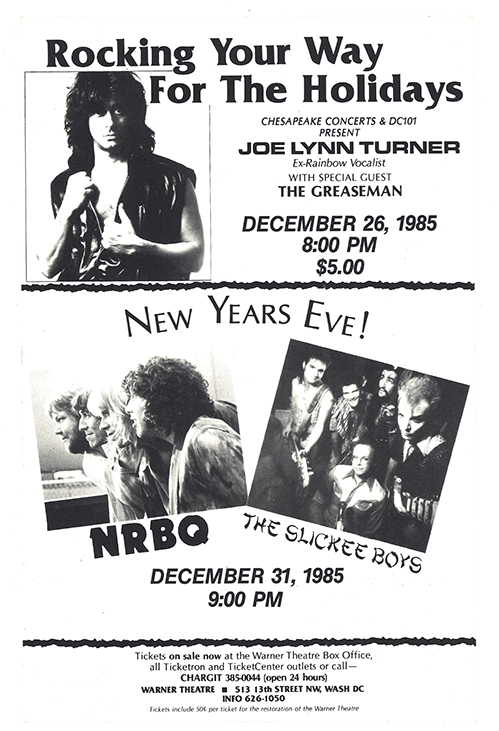

New Year's Eve at the 9:30 Club, circa 1980-1989