Washington D.C. remained abuzz from the fallout following the arrest and conviction of Mayor Marion Barry the previous year. Barry, who, amid the trial, did not run for a fourth term in 1990, instead found himself serving a six month prison sentence beginning in October 1991.1 Citizens grappled with Mayor Barry’s fall from grace as the city simultaneously dealt with new waves of gentrification that reshaped neighborhoods and, often, pushed longtime residents out when they could no longer afford to stay. In this moment of turmoil, new voices moved to the fore of the city’s punk scene.

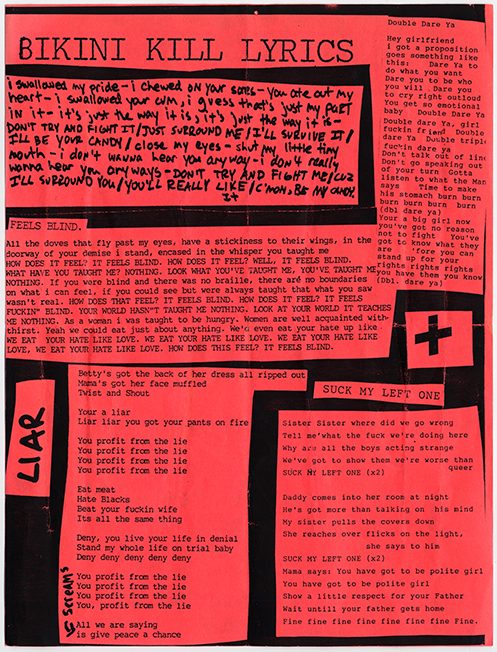

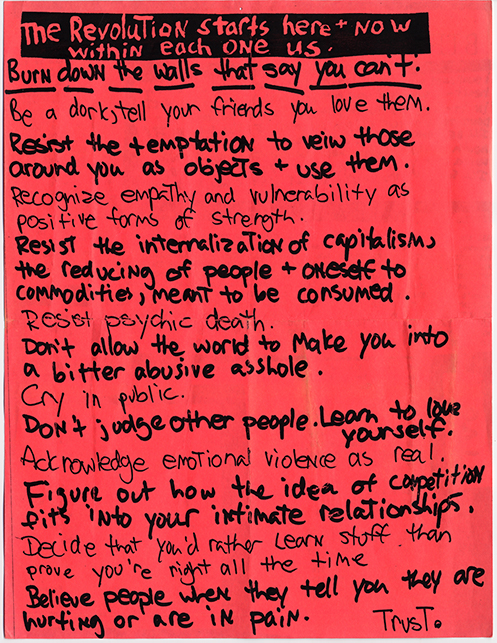

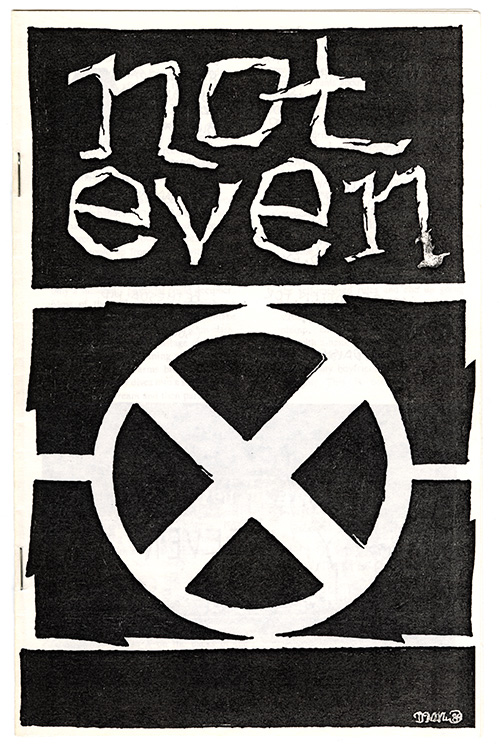

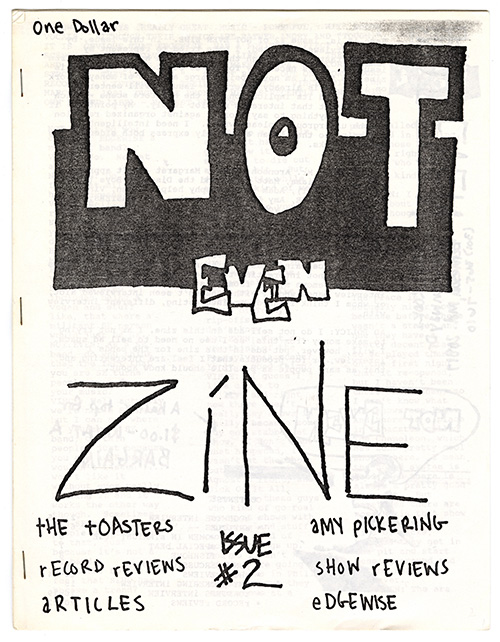

Riot grrrl, a new feminist punk movement, took shape in D.C. this year. Taking the DIY spirit and political intent fundamental to the existing punk subculture, and marshalling it in service of their feminist values, participants in riot grrrl created a culture of profound impact. Riot grrrl pushed back against the misogynistic harassment, violence, and patriarchal behavior embedded in both punk and mainstream society. Simultaneously, it celebrated womanhood and girlhood and was an expression of joy as much as outrage, despite its media reputation resting so much on the latter. Riot grrrls disseminated their ideas through concerts, recordings, activism, visual style, fliers, and zines.

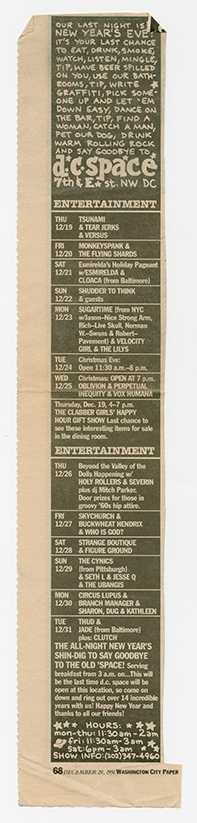

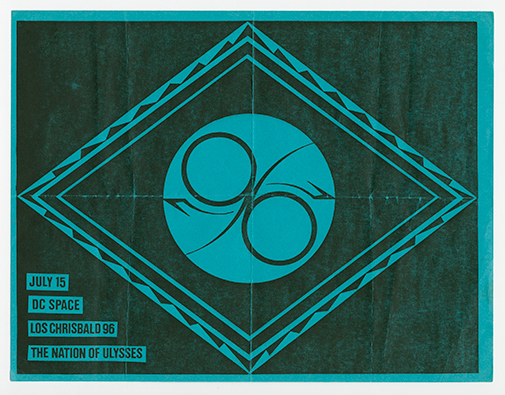

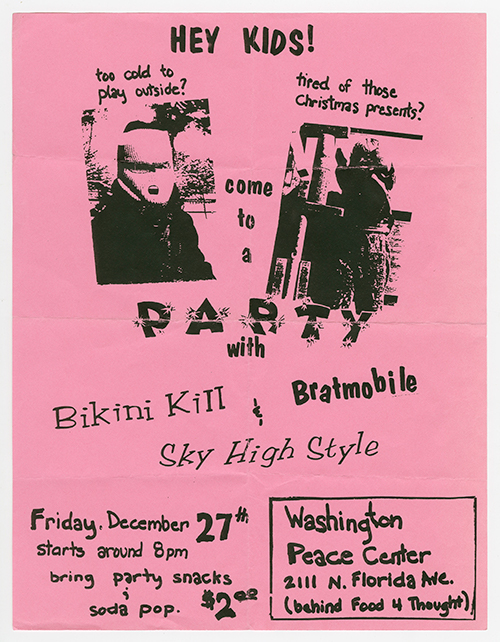

The movement was born on the West Coast with the formation of the bands Bikini Kill—composed of Kathleen Hanna, Billy Karren, Kathi Wilcox, and Tobi Vail—in 1990 in Olympia, Washington, and Bratmobile, which began with Allison Wolfe and Molly Neuman in Eugene, Oregon, playing its first show in early 1991. Neuman was from the D.C. area and went home for winter break from college at the end of 1990. She attended a Nation of Ulysses show at dc space on December 26 at which K Records head Calvin Johnson introduced her to guitarist Erin Smith, a Bethesda, Maryland resident. Smith had co-edited the fanzine Teenage Gang Debs with her brother, Don, since 1988, affectionately chronicling 1960s and 1970s pop culture minutiae. Neuman was already aware of Smith before they met, with Neuman later approvingly describing Smith as “a cult figure” in Olympia for her endearingly obsessive fandom of K Records. That night at dc space, the pair agreed to send each other their respective zines, as Neuman had recently started publishing Girl Germs with Wolfe back west. “We started exchanging zines and we were pen pals and then we were calling on the phone and that's how it started,” Smith recalled.2

...

Neuman returned to D.C., this time with Wolfe, for spring break in 1991 and asked Smith if she wanted to play some music. Smith had already been collaborating with Christina Billotte of Autoclave—whose first single, Go Far, came out on Dischord and K Records in 1991—so the pair joined Wolfe, Neuman, and D.C. musician Jen Smith to briefly form a band they called Bratmobile DC. Billotte and Jen Smith departed the project months later and Wolfe, Neuman, and Erin Smith continued on as Bratmobile, playing their first show as a trio at Fort Reno Park in July.

Bratmobile and Bikini Kill had both settled temporarily in D.C. during the summer of 1991 and were closely aligned with the Nation of Ulysses and the group home that band members lived in, dubbed “the Embassy.”3 Bikini Kill had just completed a cross-country tour with Nation of Ulysses and the rapt reception they received at the tour’s final show on June 27 at d.c. space was among the reasons convincing them that D.C. might be worth sticking around in for a while. “I was completely enthralled by the band, especially Kathleen, who could deliver songs with such emotion, yet be concerned that the girls had room up front,” Tsunami guitarist and Simple Machines co-leader Kristin Thomson remembered. “It was really inspiring.”4

D.C. politics and activism helped inspire the riot grrrl movement's name and political intent. On May 5, protests overtook the Mount Pleasant neighborhood following the shooting of a Salvadoran man, Daniel Enrique Gomez, by a Black female D.C. police officer, which left Gomez paralyzed. Later referred to as the Mount Pleasant Riot or the Mount Pleasant Disturbance, the protest continued for several days, bringing attention and, eventually, a formal study and subsequent interventions in service and treatment of DC’s growing Hispanic population.5

For the women growing their own feminist-inspired punk scene in DC that summer, the idea of resistance was alluring. Jen Smith—a Mount Pleasant resident who, aside from her stint in Bratmobile DC, played in the band Rastro!—was inspired by the activist intent of the riots, but felt an uneasiness about some of the thrill seeking participation she noticed her non-Salvadoran punk friends engaging in that tumultuous week. When some of her housemates at the Embassy joined the conflict, she stayed home. “I thought it was not cool to go up, because I didn’t feel like I knew enough about [it]—I wasn’t going to be an ally. And the people from our house weren’t going to be allies to Salvadorians; they're just there for the ruckus.”6 Despite this, seeing her Salvadoran neighbors push back against an oppressive system imbued her with an urgency to bring the same energy to feminist activism. The words “girl riot” ran through her head in the days that followed and, in a letter to Wolfe, she mentioned the phrase alongside her desire for change that summer.7

In early July, Bikini Kill’s Hanna, Bratmobile’s Wolfe and Neuman, and Jen Smith had the idea to create a weekly zine that would publish for the rest of the summer. An immediate outlet for their interests, concerns, and activism, the zine would be an ephemeral publication, meant to be distributed and consumed quickly, a testament to the galvanizing creative spirit unfolding rapidly that summer. The group named the zine Riot Grrrl, pulling inspiration from Jen Smith’s “girl riot” phrase, as well as Tobi Vail’s tongue-in-cheek spelling of “grrrl” in an issue of her zine, Jigsaw.8 The name of the zine, like the riot grrrl movement that followed, intentionally names and reclaims girlhood—as opposed to womanhood—as an ephemeral moment of becoming rather than arrival. It couples a feminist reclamation of girlhood from patriarchal expectations with an untamed spirit through the indication of a growl through the spelling of “grrrl.” The first issue of Riot Grrrl was initially distributed at a backyard party held at Bratmobile guitarist Erin Smith's parents' house, with the second issue following a week later at Bratmobile’s Fort Reno concert.

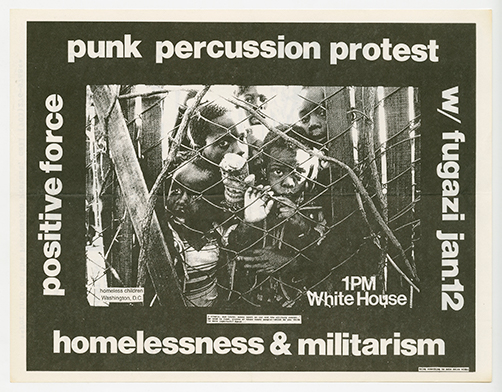

Building off of the momentum of the zine, Hanna organized a meeting at the Positive Force house in Arlington, Virginia for July 24.9 The meeting was announced in the third issue of Riot Grrrl and was described as “an all girl meeting to discuss the status of punk rock and revolution. [...] We’ll be talking about ways to encourage higher female scene input [and] ways to help each other learn to play instruments [and] get stuff done.” The riot grrrl movement bloomed from these meetings, which gave participants a forum for communication, connection, catharsis, and inspiration.

According to riot grrrl historian Sara Marcus, another key event in the development of riot grrrl from 1991 was the International Pop Underground Convention (IPU) punk and indie rock music festival in Olympia that August, particularly the “Girl Night” concert that kicked off the gathering.10 Primarily organized by Calvin Johnson and Candice Pedersen of K Records, the festival embodied the independent, DIY ethos of punk. Unlike many rock music festivals that were driven by a desire for bands to be seen and courted by major labels, IPU stood in opposition to that, extolling the pleasures of independence, unfettered creativity, and a true alternative culture. “Here you have this incredibly unpretentious environment where people are respectful of each other, bonding in a way that was so different from these other seminars,” said Bruce Pavitt, IPU attendee and co-founder of the Seattle record label, Sub Pop. “The atmosphere, the feeling, the vibe, emphasized camaraderie and cooperation. And it was very special.”11

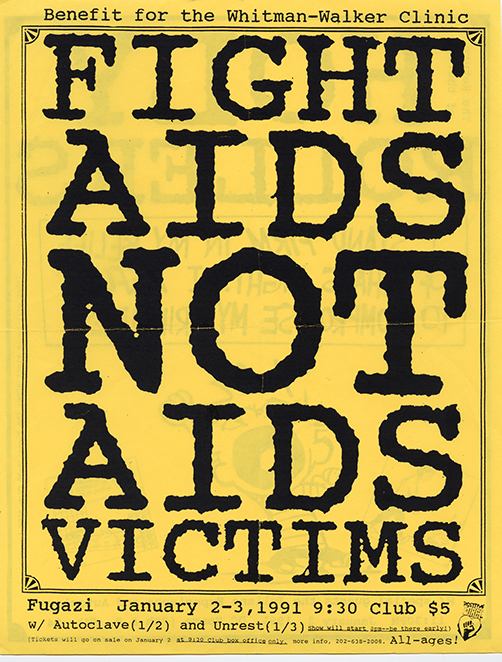

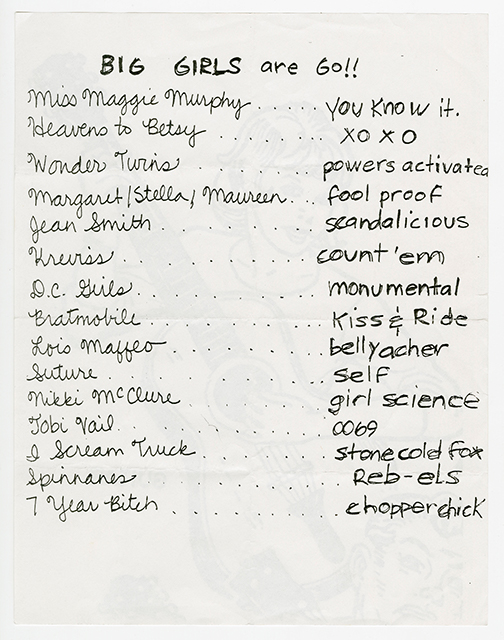

Like Fugazi and Nation of Ulysses, Bikini Kill and Bratmobile drove across the country to take part in IPU. No concert that occurred as part of the festival resonated at the time or in the years that followed like the opening “Girl Night” concert on August 20, which featured an almost, but not entirely, all female lineup of fifteen bands and performers. It included Bratmobile, as well as Tobi Vail performing solo and two of Hanna’s non-Bikini Kill projects, Wondertwins and Suture. The latter included Sharon Cheslow, the longtime D.C. scene participant who had helped shape the city’s punk subculture with her group Chalk Circle and fanzine If This Goes On. Other outstanding performers on the “Girl Night” bill, like Lois Maffeo, 7 Year Bitch, Heavens to Betsy, Rose Melberg, and the Spinanes laid plain that an exciting change was in motion. “Girl Night had unleashed something new and powerful,” wrote author and critic Jessica Hopper. “It had shown the girls a glimpse of a dazzling future of feminist truth and amps dialled to 10–and there would be no going back.”12 The IPU festival was a one-off event, its organizers resisting the urge in subsequent years to try to recapture what made those six days special, a decision that felt true to the essence of the gathering.

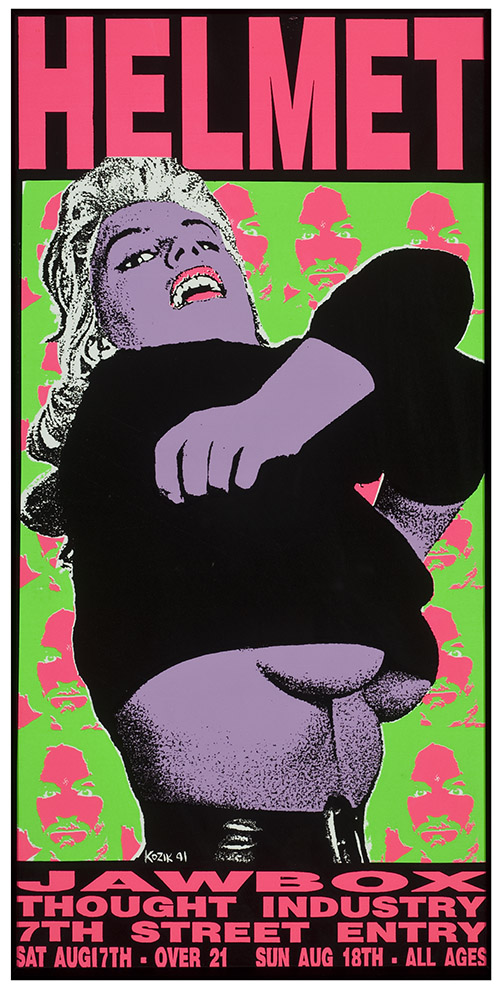

Aside from the ascent of riot grrrl, 1991 was an eventful year in the D.C. punk community overall. Simple Machines continued to grow, issuing the Baltimore quartet Lungfish’s debut full length album, Necklace of Heads, as well as two more releases in its Machine compilation single series, titled Pulley and Screw, featuring Nation of Ulysses, Bricks, Jawbox, and Velocity Girl. 1991 also saw the debut of the label’s “Mechanic’s Guide,” a twenty-page booklet that offered a step-by-step guide to releasing an album, from pressing plants to graphic design. When the guide was featured in Sassy magazine—one of the few mainstream magazines to offer serious coverage to both riot grrrl and indie rock culture—Simple Machines co-owners Jenny Toomey and Kristin Thomson received more than eight hundred requests for the booklet, which served as a substantial distribution of DIY ideals and practice in the pre-internet era.13 Toomey and Thomson’s band, Tsunami—including bassist Andrew Webster and drummer John Pamer—debuted in 1991, releasing the Cow Arcade demo tape and the Headringer 7-inch EP. The quartet would soon become one of the leading groups of the scene, fitting in alongside the volume, edge, and activism of most Dischord bands, while adding new textures to the subculture’s sound.

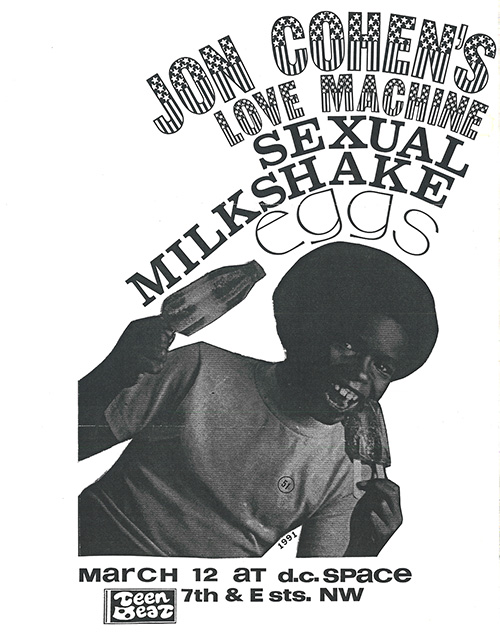

Simple Machines also jointly sponsored—alongside Teen-Beat and Slumberland—the Lotsa Pop Losers festival, which occurred on October 26 and 27 at the Bethesda American Legion Hall in Bethesda, Maryland and dc space downtown. “We had a lot of experience organizing shows because of our involvement with Positive Force and from being in a band and booking tours,” Toomey recalled. “But Lotsa Pop Losers was very different from a Positive Force show. It was way more whimsical and it was a joint effort, and it was a moment [where] the newer labels were finding each other, and imagining the possibilities of what we could do together.”14

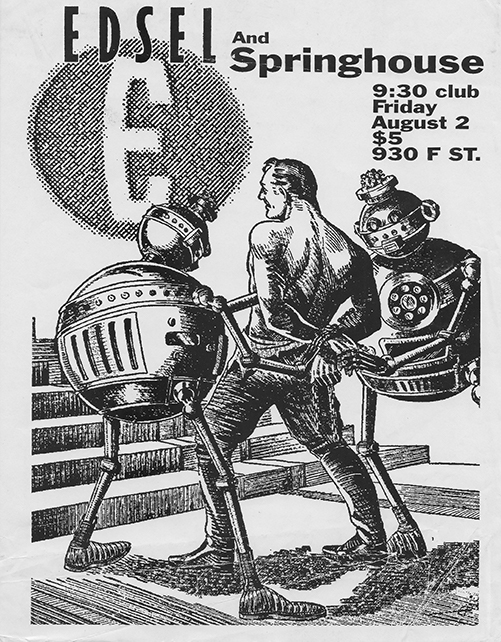

In addition to Velocity Girl and Tsunami (along with other DC bands like Edsel, the Lilys, Lorelei, and High Back Chairs), the festival featured Unrest, whose music had developed from its noisier, occasionally obtuse beginnings into a skilled, tuneful indie pop. D.C.’s noise pop scene now rivaled punk and hardcore in local popularity, which the Lotsa Pop Losers festival highlighted. “To a great extent, if you look at Positive Force shows of that era being a bit too domineering in style and content, this was a chance for people without a narrow point of view to stretch and create a two-day D.C. event that was every bit as interesting and DIY [as Positive Force],” said Don Smith, who hosted a radio show on the University of Maryland’s WMUC-FM in addition to his co-editing duties on Teenage Gang Debs fanzine. “I’d talk to Positive Force people about setting up shows, and they’d want to vote on them and essentially ‘vote them out.’ Here, the indie crowd could take what we had experienced already from Positive Force, but create an experience that was important and unique.”15

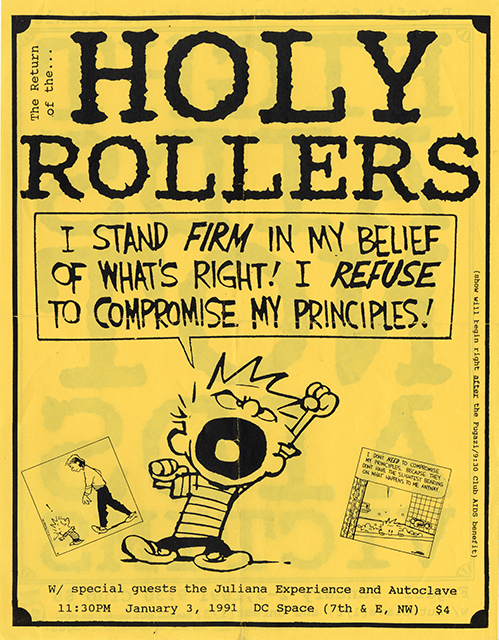

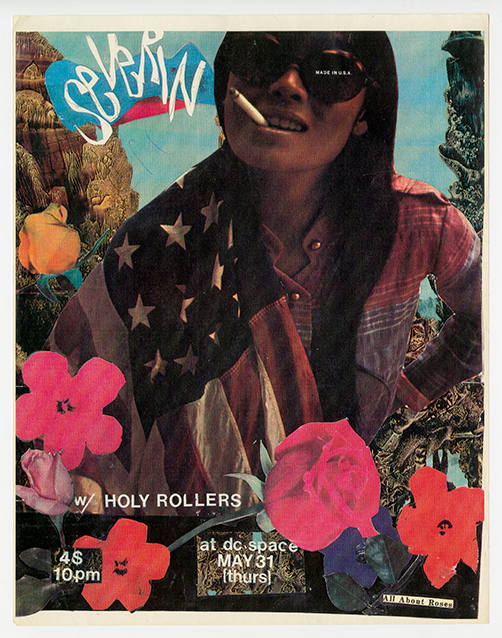

Dischord Records would also have a momentous year in 1991, issuing the debut albums from Jawbox, Nation of Ulysses, and Dischord co-founder Jeff Nelson’s power pop group the High-Back Chairs. Holy Rollers released Fabuley which, led by songs like “Perfect Sleeper” and “What You Said,” was a notable creative leap forward from their debut the year earlier. Shudder to Think, who had been rising through the scene since the late 1980s, released their third album, Funeral at the Movies, in 1991 on Dischord. Building off of the previous year’s Ten Spot album (also on Dischord), Funeral at the Movies captured a band who was like none other in the D.C. punk scene, if anywhere. Craig Wedren’s sui generis vocals and lyrics were elevated further by Shudder to Think’s expansive, evocative post-hardcore music, as exemplified on the title track (which evinced the surprising influence of Los Angeles alternative rock giants Jane’s Addiction through its airy, unusual chords and dramatic guitar solo) and the opening track, “Chocolate.” While not as commercially popular as some of their peers on Dischord, no one on the label was making music as challenging and innovative within the post-hardcore context as Shudder to Think in 1991.

Dischord also released important chapters from its back catalog—Rites of Spring, Dag Nasty, Beefeater—on compact disc for the first time, the format allowing for multiple releases by a band to be compiled onto a single disc. Holy Rollers and Shudder to Think also respectively saw their new records paired on compact disc with their albums from the previous year, potentially blurring the differentiation between each creative work for some fans who listened on compact disc rather than the cassette or LP formats. Regardless, the further expansion of Dischord’s back catalog onto compact disc greatly increased the music’s reach and accessibility, as 1991 marked the first year that the compact disc was the dominant format across the music industry, in terms of sales.16

The biggest release on Dischord’s schedule this year was Steady Diet of Nothing, Fugazi’s follow-up album to the groundbreaking Repeater. The album would ascend sales and college radio airplay charts like no other prior Dischord release, with the widely circulated Pulse! Magazine referring to the group as “the one remaining beacon of hope in rock ‘n’ roll and for the country’s youth in general. No lie.”17 When asked later if he agreed with Pulse!’s assessment, Fugazi guitarist/vocalist quickly asserted, “No! I think it’s bullshit.”18 Tracks like “KYEO,” “Nice New Outfit,” and the smoldering “Long Division” advanced the artistic successes of Repeater, moving into new aesthetic territory, even if the album’s airless production sound was later viewed by band members as a misstep.

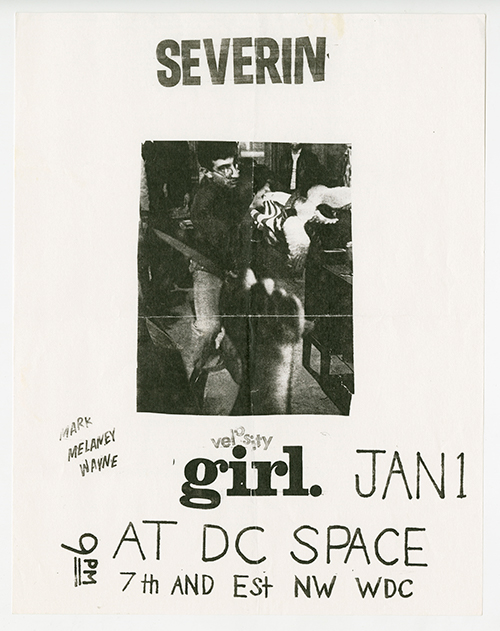

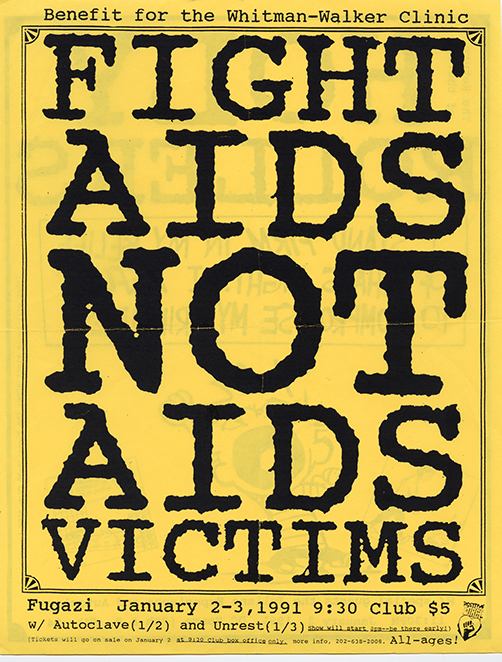

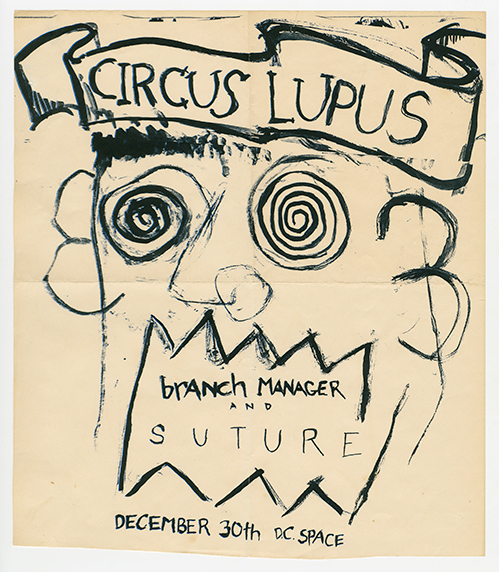

By year’s end, D.C. would see the closure of longtime venue dc space, at the corner of 7th and E Streets NW, another harbinger of the city’s increased gentrification. The club went out with a series of concerts including Velocity Girl, Tsunami, Holy Rollers, Severin, Circus Lupus, Branch Manager, and Shudder to Think, among others. Although it initially seemed that dc space might relocate, rather than close entirely—a farewell advertisement in the Washington City Paper read “say goodbye to the old ‘Space” and “this will be the last time d.c. space will be open at this location”—the club never returned after the final concert on December 31. “For years, dc space has been arguably the only, and certainly the only reliable, venue for original music outside the mainstream,” Eve Zibart wrote in The Washington Post, perhaps forgetting the 9:30 Club. “Hardcore, improv, go-go, gothadelic, zombie grunge, surf garage, metal, indie—all the new adventurers and spoofers and counterrevolutionaries who couldn't draw big enough crowds for more commercial clubs were welcomed here.”19

As seminal as the events of 1991 were, they were also, in a way, the end of something. The September 24 release and subsequent runaway commercial success of Nevermind, the major label debut album by Seattle’s punk-rooted Nirvana (whose first album was on Sub Pop), started a titanic shift within punk and indie rock. The idea that a group from those subcultures could never break out of the underground to dominate mainstream music had been punctured. As Jessica Hopper later observed of the International Pop Underground Convention, “attendees [...] had no idea that they were in the twilight of an era. [...] The underground would divide into two halves: one made up of bands wishing to be the next Nirvana, vying for major label contracts, the other of fiercely indie forces who would just dig in deeper, bracing themselves against commercial interests.”20 Even the D.C. punk scene, notorious for its fierce independence and anti-corporate attitudes, would see a similar divide develop in the very near future.

Further Listening

Autoclave. Go Far. Dischord Records/K Records, 7-inch EP.

Avail. Who’s to Say What Stays the Same. Sunspot Records, 7-inch EP.

Battery. Battery. Deadlock Records, 7-inch EP.

Bikini Kill. Revolution Girl Style Now. Self-released, album.

Black Tambourine. By Tomorrow. Slumberland Records, 7-inch EP.

Brief Weeds. A Very Generous Portrait. K Records, 7-inch EP.

Desiderata. Desiderata. Dischord Records/Desichord Records, 7-inch EP.

Fugazi. Steady Diet of Nothing. Dischord Records, album.

High-Back Chairs. Of Two Minds. Dischord Records, album.

Jawbox. Grippe. Dischord Records, album.

Nation of Ulysses. 13-Point Program to Destroy America. Dischord Records, album.

Nation of Ulysses. The Birth Of The Ulysses Aesthetic (The Synthesis Of Speed And Transformation). Dischord Records, 7-inch EP.

Rake. Motorcycle Shoes. VHF Records, 7-inch EP.

Senator Flux. Storyknife. Emergo Records, album.

Severin. “Fire and Sand”/“People Are Wrong.” Dischord Records/Superbad Records, 7-inch single.

Shudder to Think. Funeral at the Movies. Dischord Records, album.

Skewbald/Grand Union. Skewbald/Grand Union. Dischord Records, 7-inch single. (Recorded in November 1981, but not released until 1991)

Tsunami. Cow Arcade. Self-released, demo cassette.

Tsunami. Headringer. Simple Machines, 7-inch EP.

Unrest. Cherry Cherry. Teenbeat Records/Hemiola Records, 7-inch single.

Unrest. A Factory Record. Sub Pop/Teenbeat Records, 7-inch EP

Unrest. Yes She is My Skinhead Girl. Teenbeat Records/K Records, 7-inch single.

Various. DsCene. More Than Sound Records, compilation cassette.

Various. Give Me Back. Ebullition Records, compilation album.

Various. Pulley. Simple Machines, 7-inch compilation EP.

Various. Screw. Simple Machines, 7-inch compilation EP.

Materials are drawn from the Paul Bushmiller collection on punk, the Sharon Cheslow punk flyers collection, the John Davis collection on punk, the D.C. punk collection, the D.C. punk and indie fanzine collection, and the Robbie White collection on the Slickee Boys.

Tap or hover over an image to learn more.

FLIERS & POSTERS

ZINES

PHOTOGRAPHS

EPHEMERA