The year was marked by beginnings both hopeful and terrifying, immediate and lingering. Perhaps the most portentous beginning was the initial reporting on the HIV/AIDS epidemic. On May 18th, New York Native, a newspaper focused on the gay community published the first article outlining the limited information circulating about the syndrome. While the Center for Disease Control published initial findings weeks later, the crisis went largely ignored by the Reagan administration for years to come.1 The Reagan Administration’s first year was chaotic, defined by the Economic Recovery Tax Act which shaped the economic effects of his presidency and marred by the attempt on Reagan’s life outside of the Washington Hilton.

In the District, the decentralized state of the city government paired with a lack of oversight and a recent blitz of municipal hiring led to major shortcomings in the 1981 budget. In an attempt to address the incredible debt the city faced despite annual budget surpluses, Barry began reducing services and city employees, disproportionately affecting the unhoused and working class city workers.2 The changes resulting from first terms of the Reagan and Barry administrations were beginning to feel palpable.

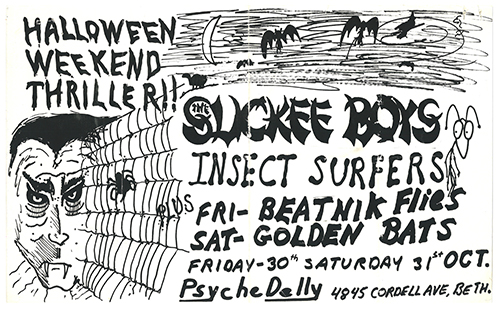

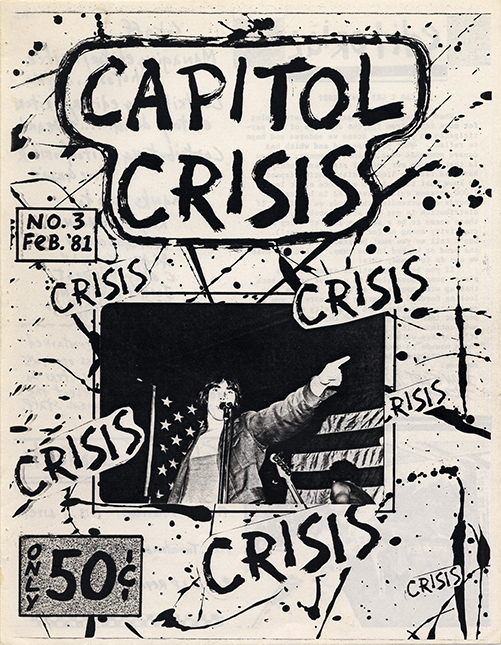

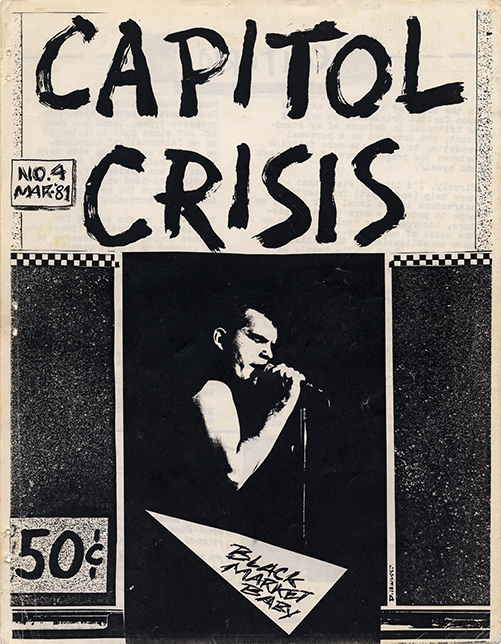

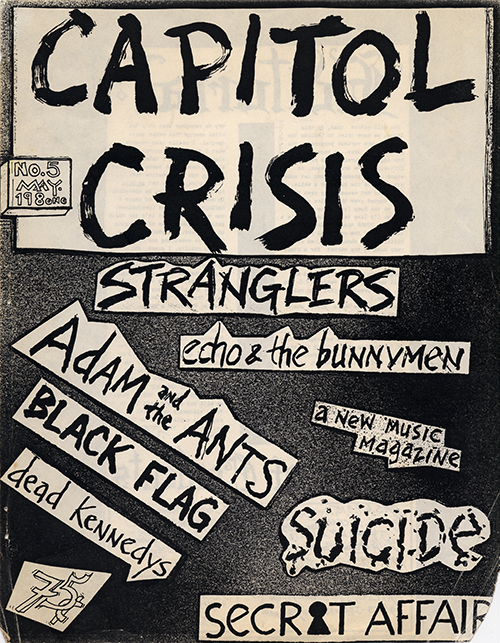

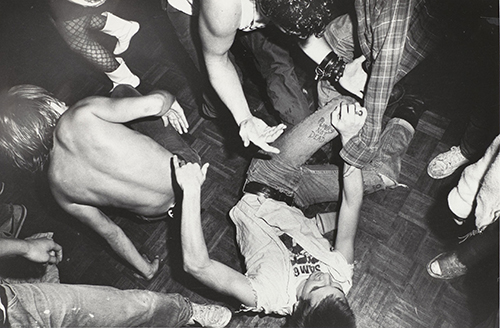

Likewise within the city’s punk scene, hardcore punk fully arrived in 1981 and its presence was inescapable. In turn, this new sound and identity for D.C. punk was both embraced and pushed back against. Women had been at heart of the D.C. punk scene since its inception, whether though musicians like Martha Hull (Slickee Boys, D. Ceats), Diana Quinn (Tru Fax & the Insaniacs), Liz DuMais and Libby Hatch (both of the Shirkers) or fanzine editors like Marie Provost of The Infiltrator, Xyra Harper of Capitol Crisis, and Tina Wuelfing of Descenes. The violent dancing and casual misogyny of some hardcore lyrics and fanzines, however, alienated many women who had previously participated in the D.C. punk scene. Mary Leary, who wrote under the Marie Provost pseudonym during that period, later described the emergence of the hardcore scene as “a whole different shift in energy. I’m one of those people, if I like the music, I’m always in front. And it became so I couldn't be in the front, because it was, like, really angry white guys. [It was like] “this is a guy thing now” kind of an atmosphere.”3

...

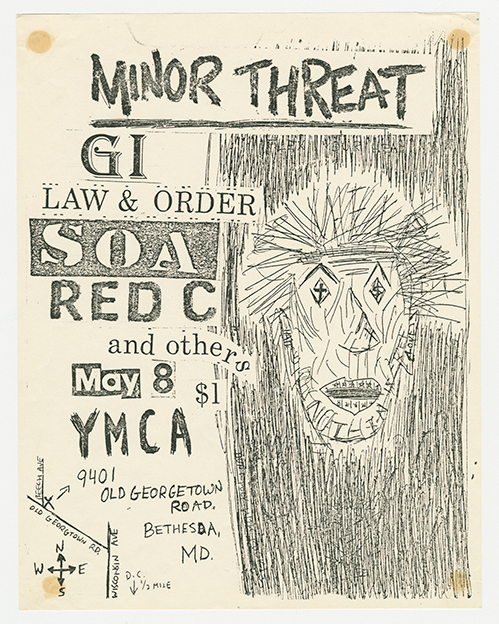

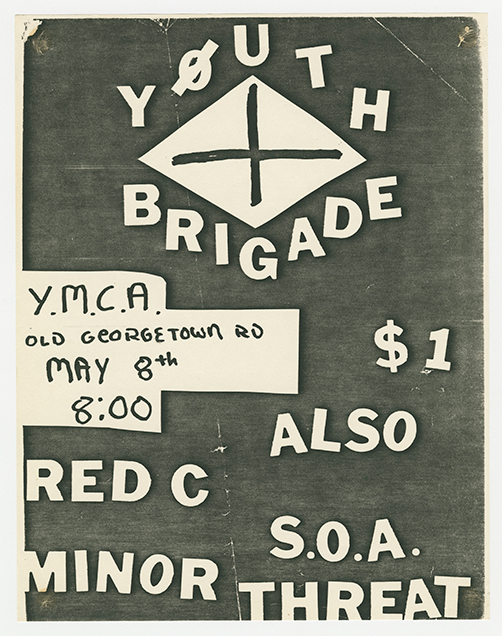

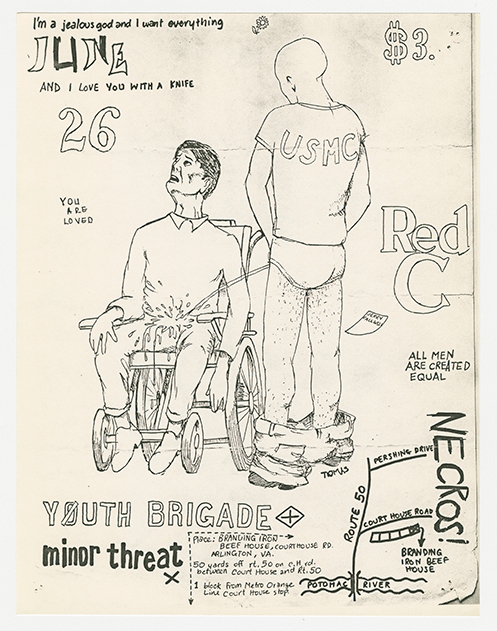

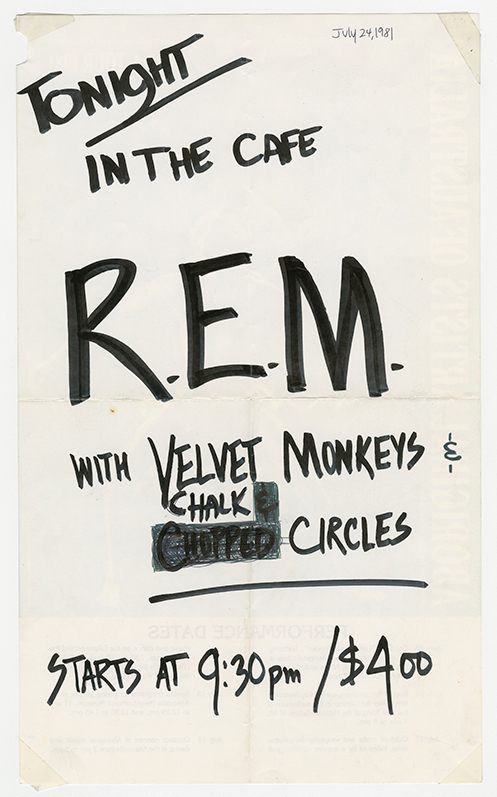

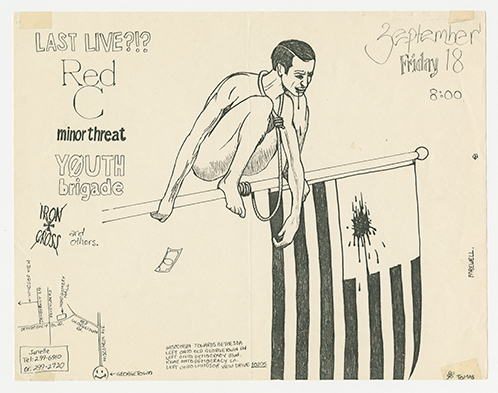

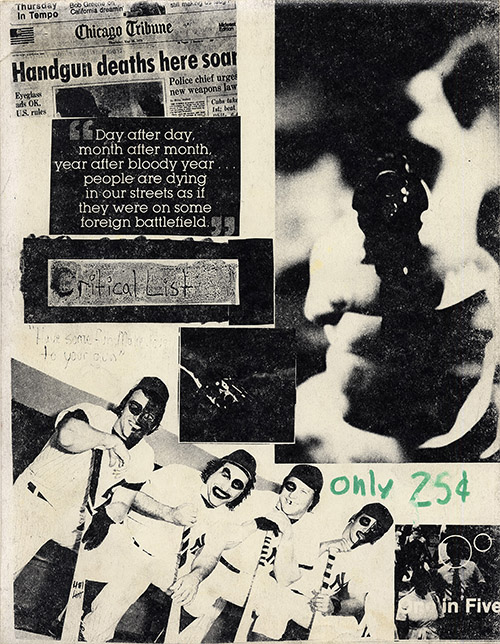

Despite this change, other women still staked their place in the developing D.C. hardcore scene of 1981. Toni Young, the bassist for the short lived Red C, was the first woman of color to play in a D.C. hardcore band.4 Chalk Circle, D.C.’s first all female punk band, debuted in 1981. The band’s fierce, angular punk rock offered a different path forward for the D.C. scene, a community that was not entirely receptive. A review of Chalk Circle’s first show in Critical List fanzine dismisses them as “a boring all-girl band,” while smirking that it was “bimbo nite [sic] at dc space.” To Chalk Circle guitarist Sharon Cheslow, the dominance of hardcore meant D.C.’s punk scene had become “more macho and less about a tight-knit group of friends,”5 but she remained drawn to the scene, noting that “Anne [Bonafede of Chalk Circle] and I still loved hardcore and went to all the shows.”

Bonafede summed up the importance of Chalk Circle’s place in the punk scene, for herself and on a wider level. “At the time, my life was lived through boyfriends or guys that I knew, rather than for myself,” she said. “With the beginning of Chalk Circle, that really changed. I could just be a drummer if I wanted to be. All my [male] friends had been playing in bands so I knew I could just do it, that was the punk philosophy. It tied very much into my feminist growth as well, just being able to say I don’t have to live through guys, I can do it myself.”6

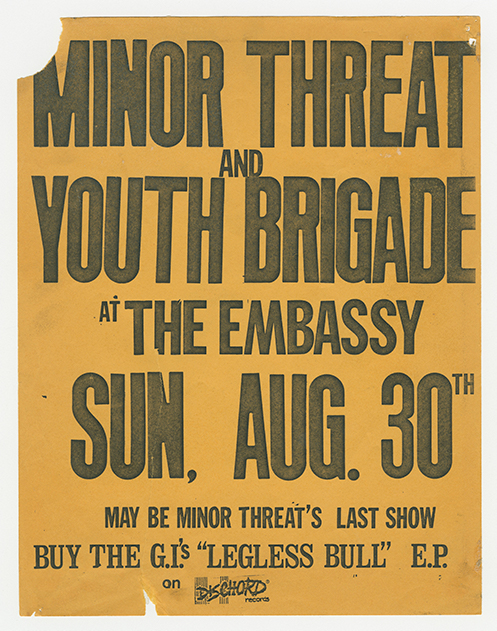

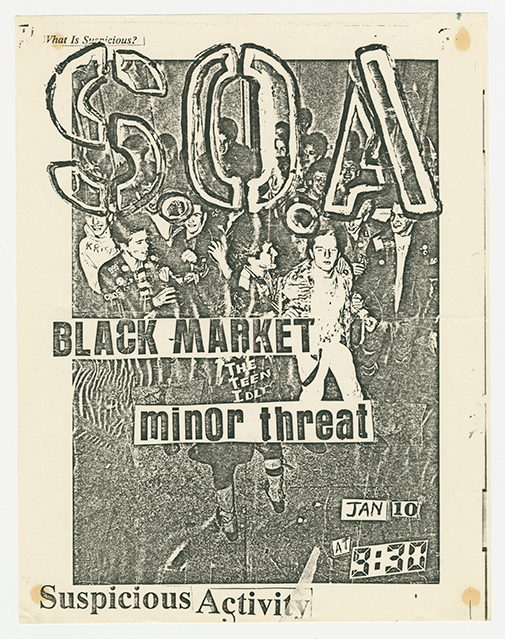

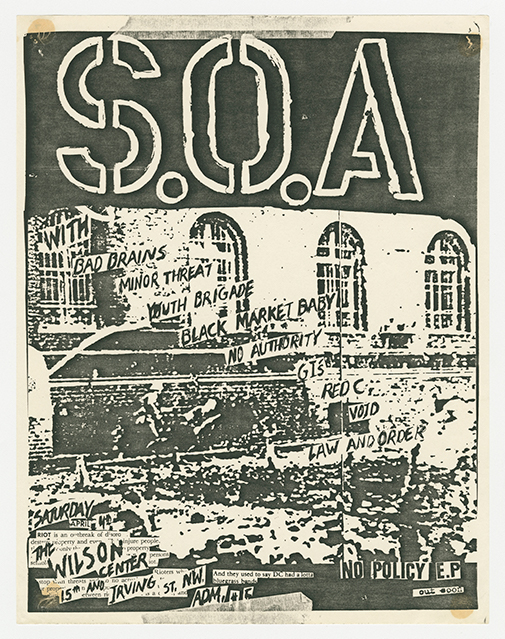

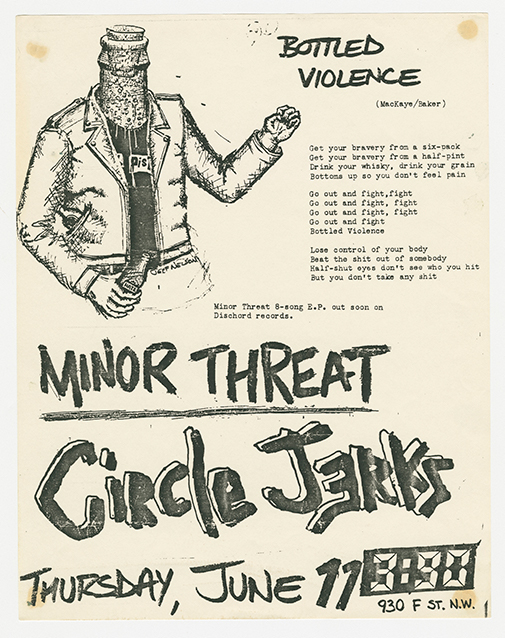

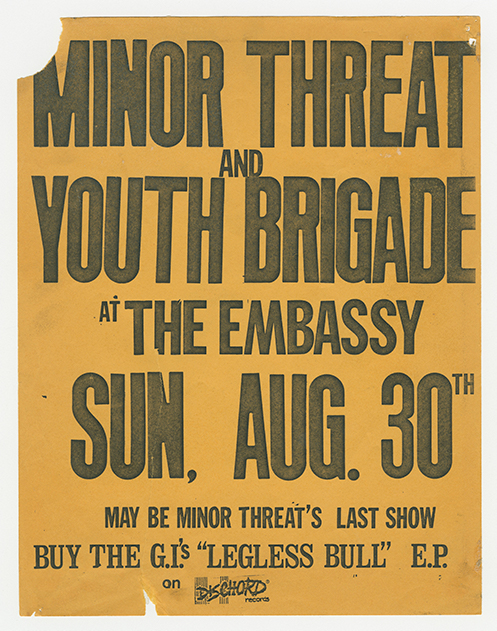

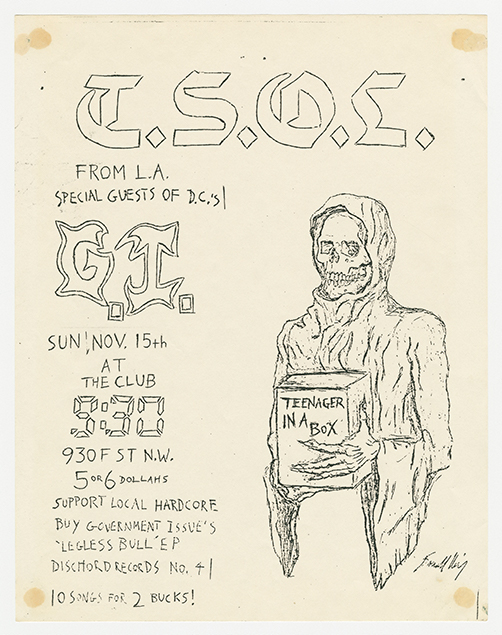

After the successful release of the Teen Idles’ Minor Disturbance EP, Dischord Records issued five more EPs in 1981. S.O.A.’s No Policy appeared in April, followed by Minor Threat’s self-titled debut in June, Government Issue’s Legless Bull in September, and Minor Threat’s In My Eyes and Youth Brigade’s Possible in December. MacKaye and Nelson, along with other friends from the D.C. punk scene, moved that year into an Arlington, Virginia house informally dubbed Dischord House. The home would become part of the base of operations for the record label for decades to come, a creative laboratory that served as living quarters, office space, and a rehearsal room for numerous scene participants.7

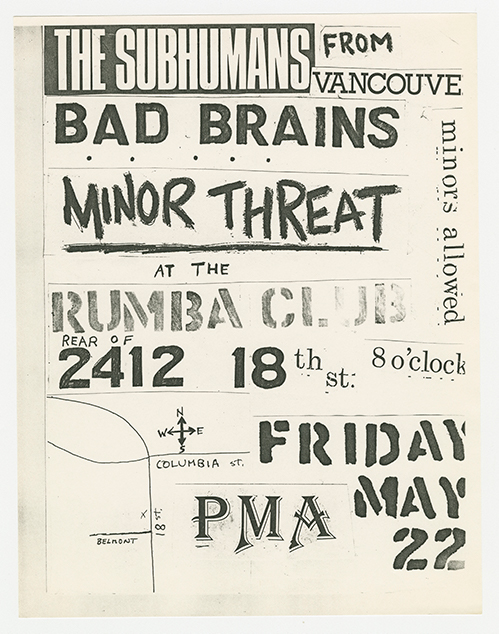

From the Dischord punks to elsewhere in the scene, the D.C. sound continued to develop in the mold of Bad Brains. Minor Threat, the Faith, and S.O.A. were made up of younger musicians who, having seen the electric performances of Bad Brains, were inspired to push the music into a louder, more confrontational space. Bad Brains’ outspoken exploration of P.M.A., a positive thought philosophy drawn from self-help author Napoleon Hill’s writings, remained influential and an inextricable part of the band’s identity.8

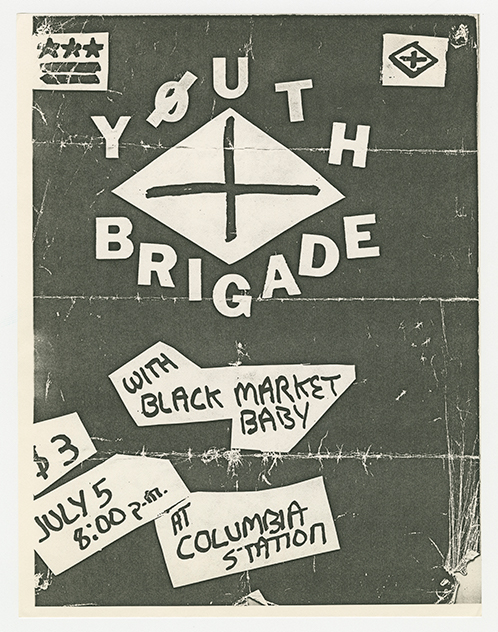

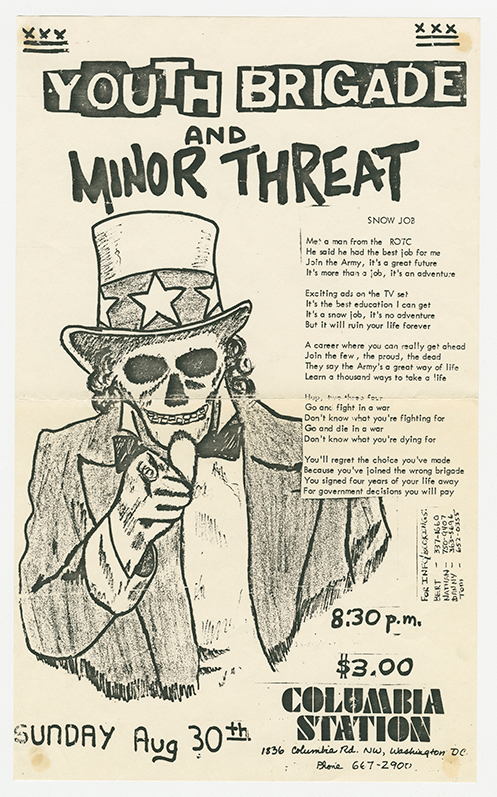

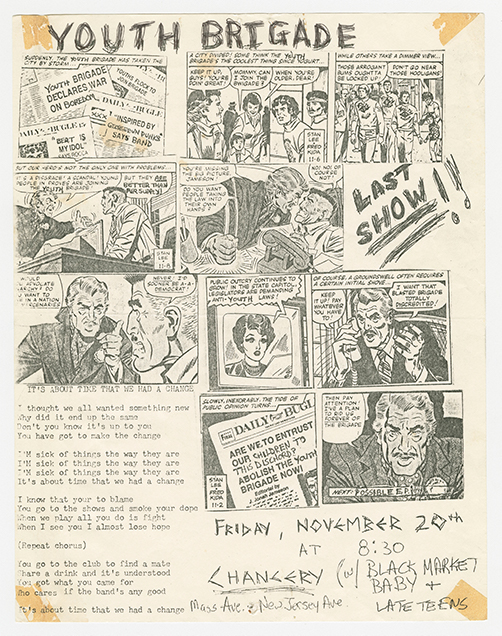

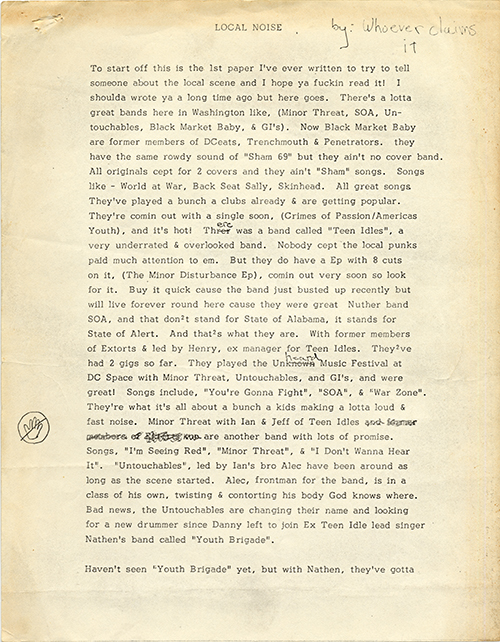

1981’s D.C. punk releases highlighted the shift in the scene towards faster tempos and the embrace of punk lyrics as a forum for barbed societal criticisms. Government Issue took aim at televangelists in “Religious Ripoff” while Minor Threat (“Straight Edge,” “Out of Step”), S.O.A. (“Lost in Space”), and Youth Brigade (“It’s About Time That We Had a Change”) assailed the hedonism entrenched in American youth culture. While many bands used their lyrics to explicitly frame their thinking, others used more oblique lyrics to reflect feelings of isolation and frustration as in S.O.A.’s “Blackout” or Black Market Baby’s “Potential Suicide.”

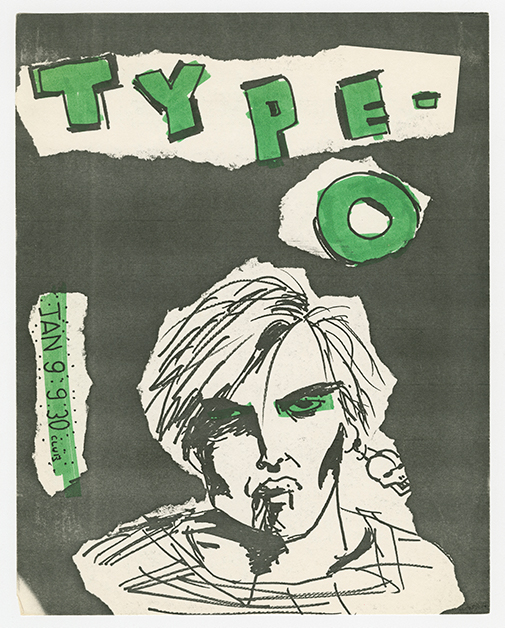

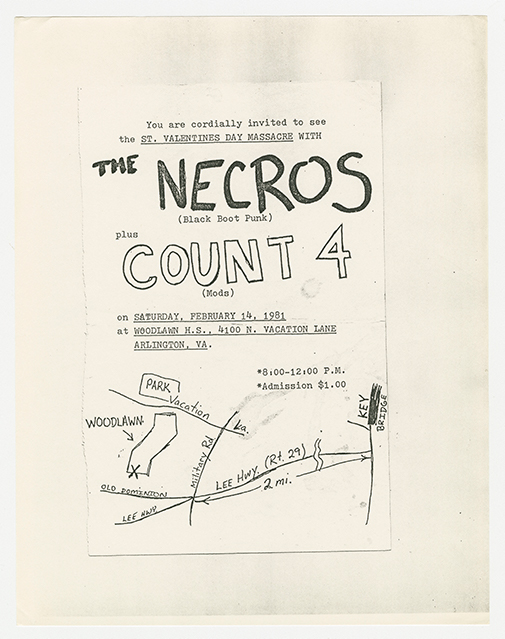

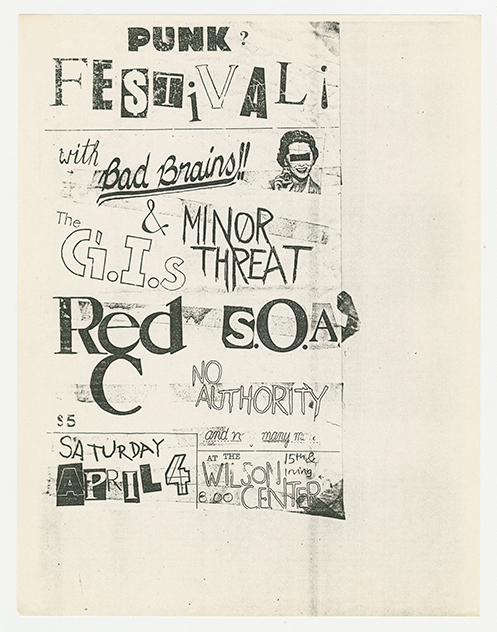

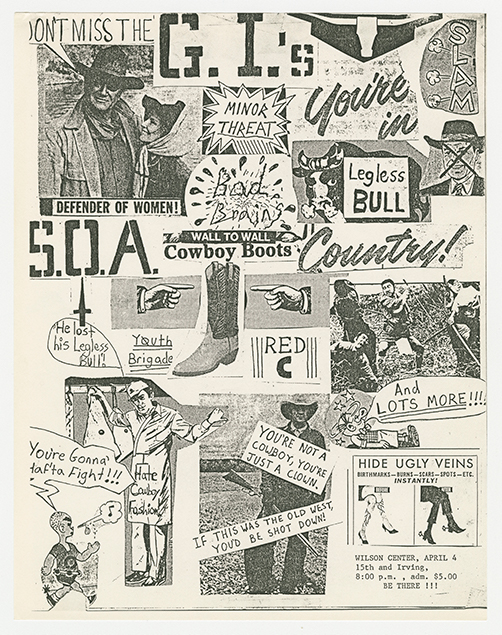

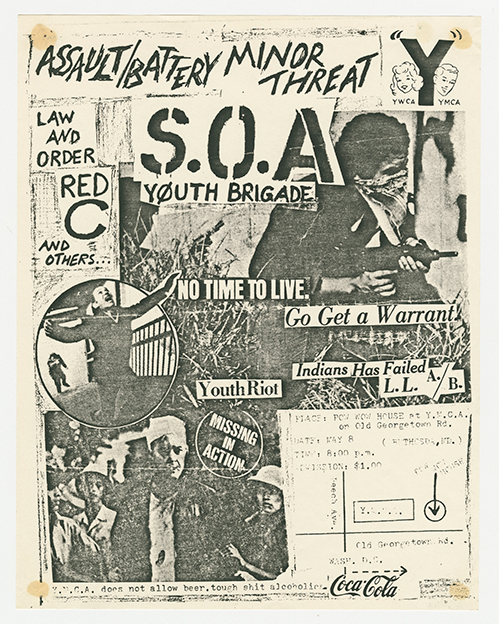

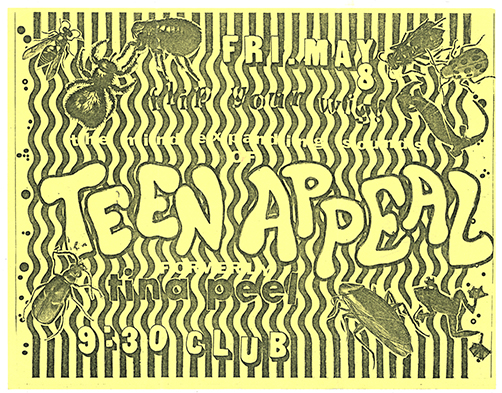

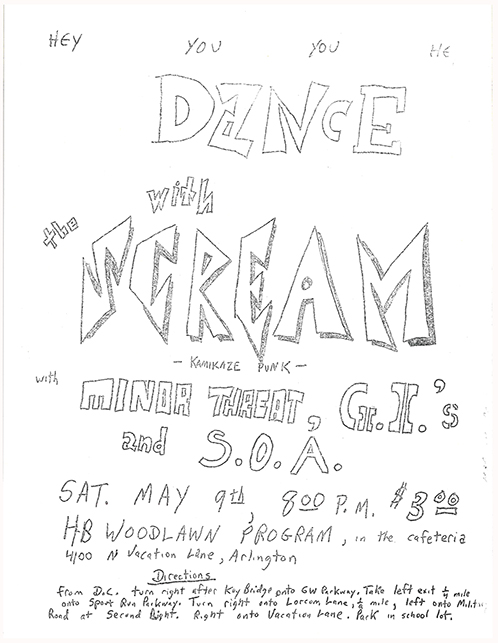

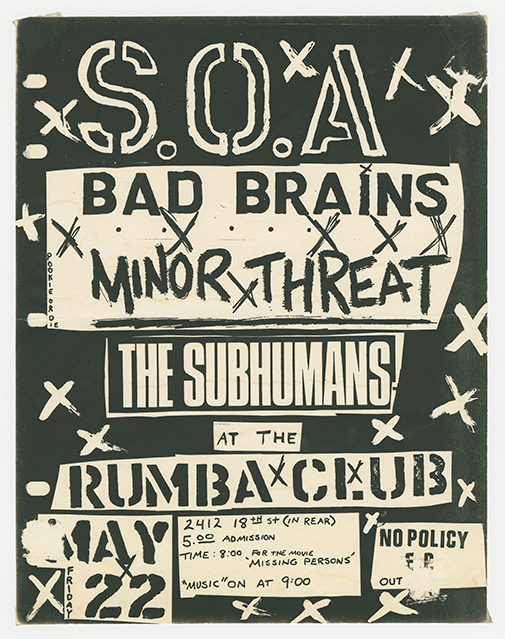

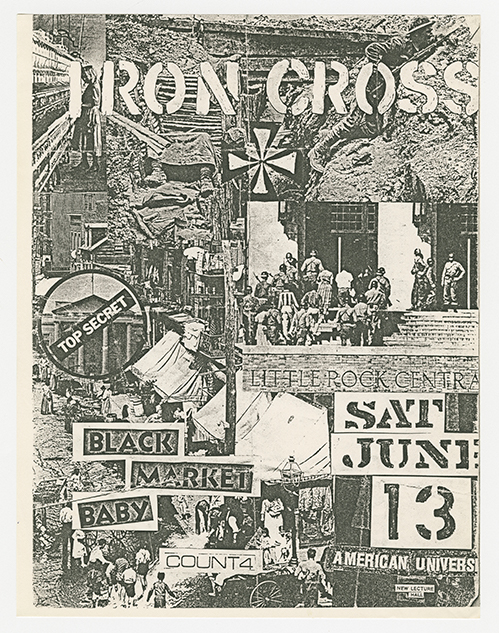

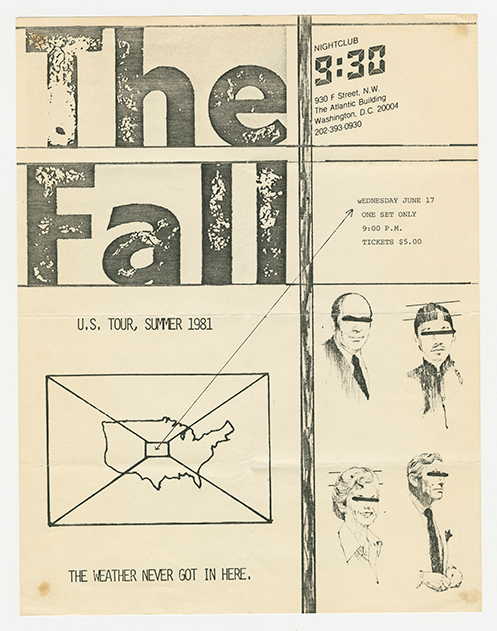

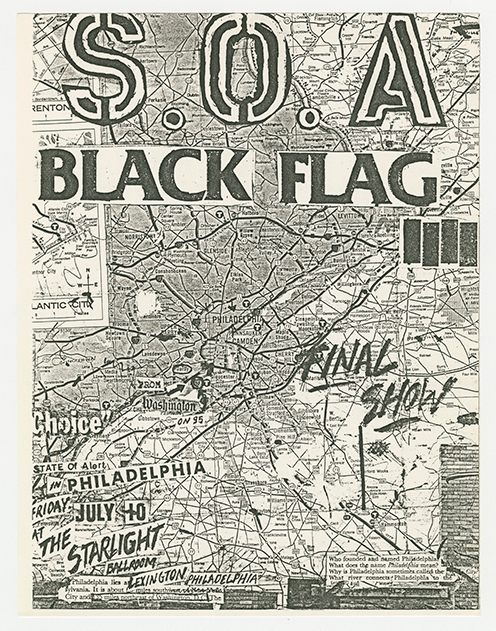

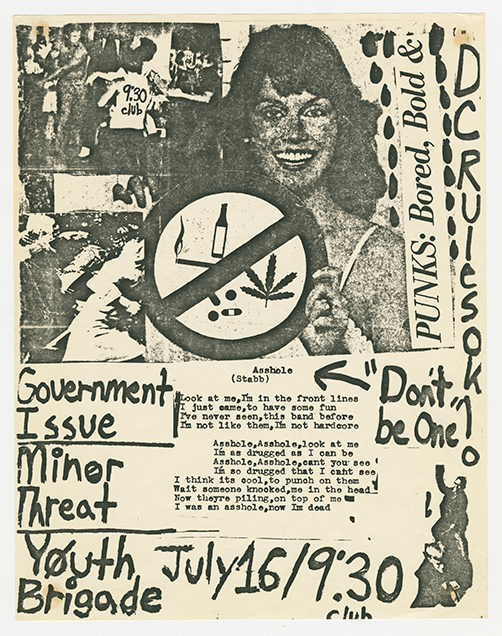

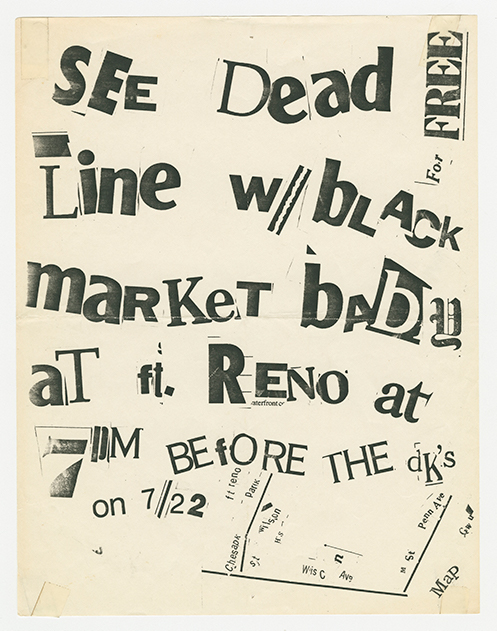

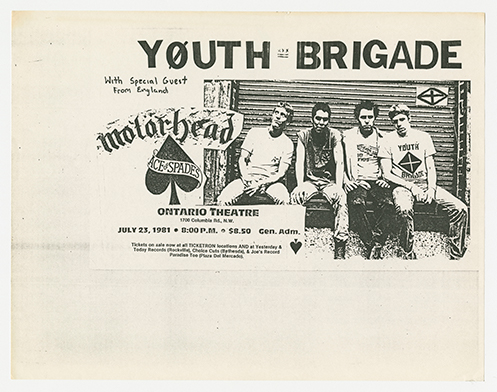

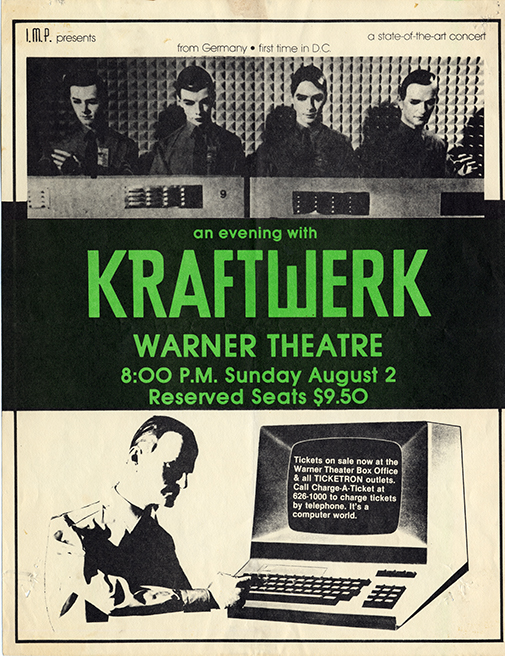

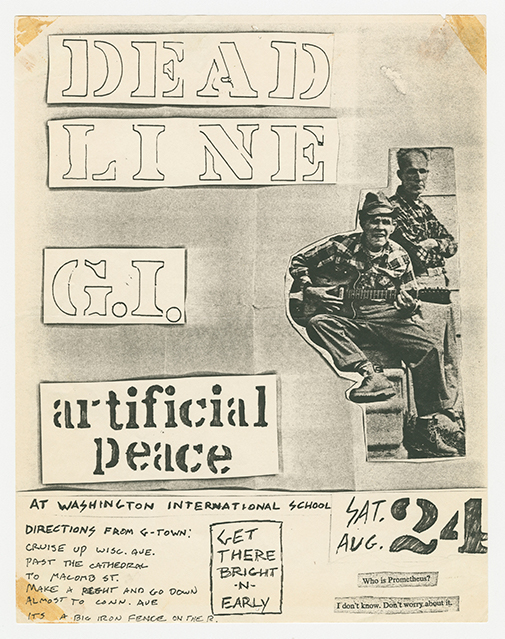

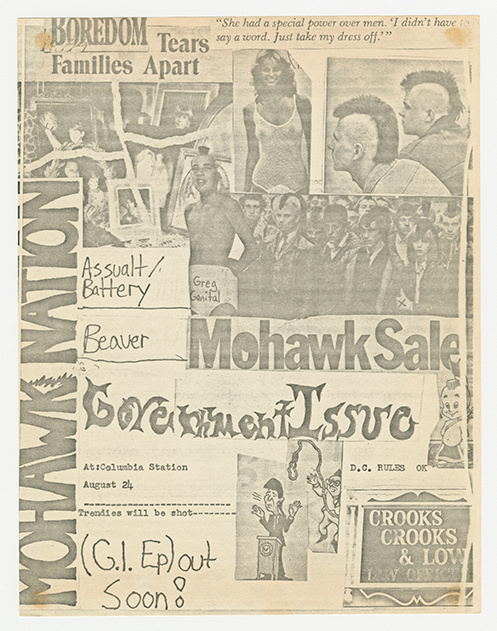

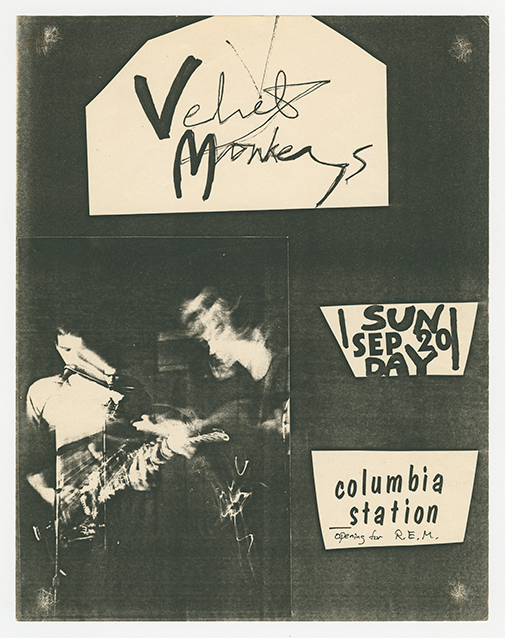

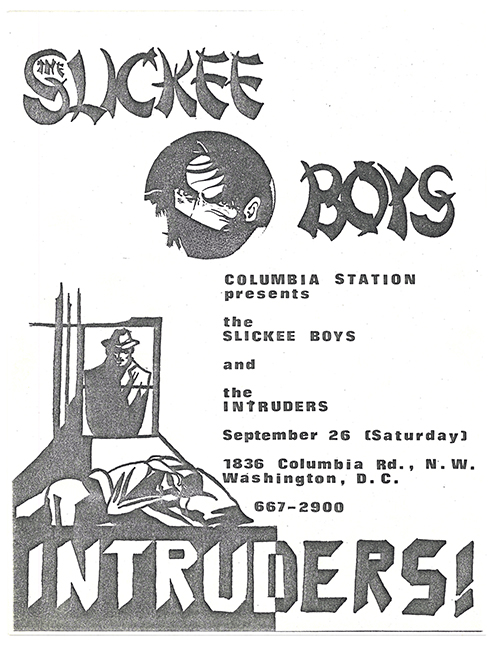

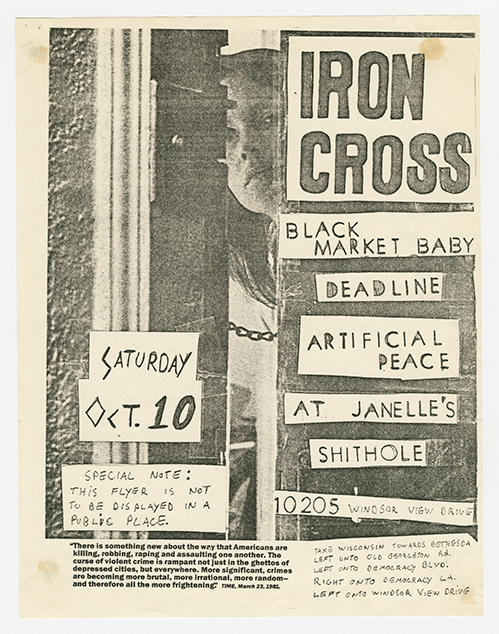

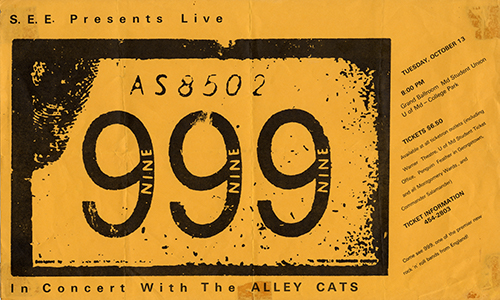

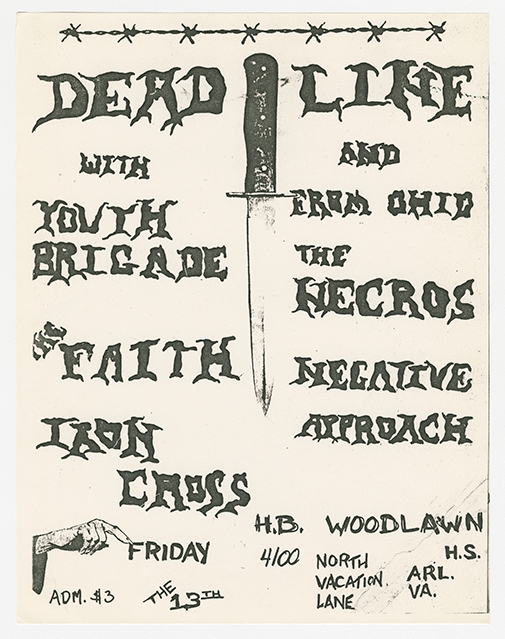

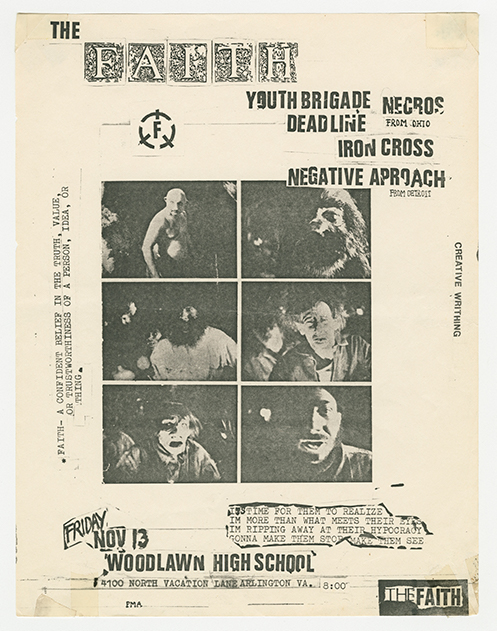

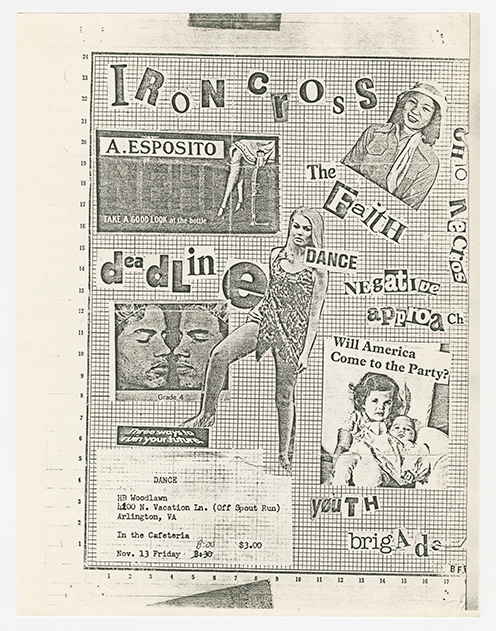

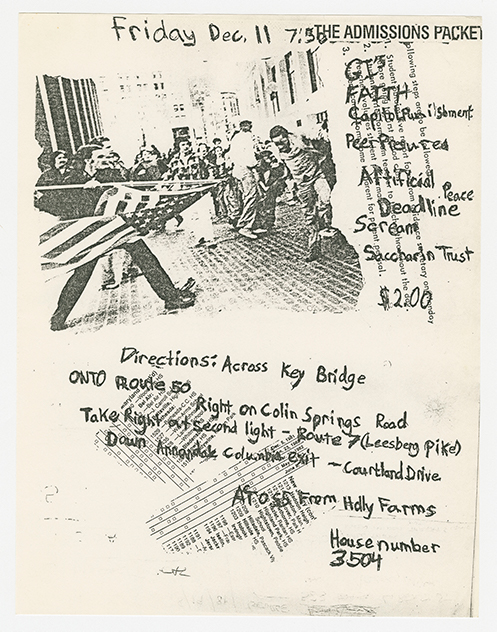

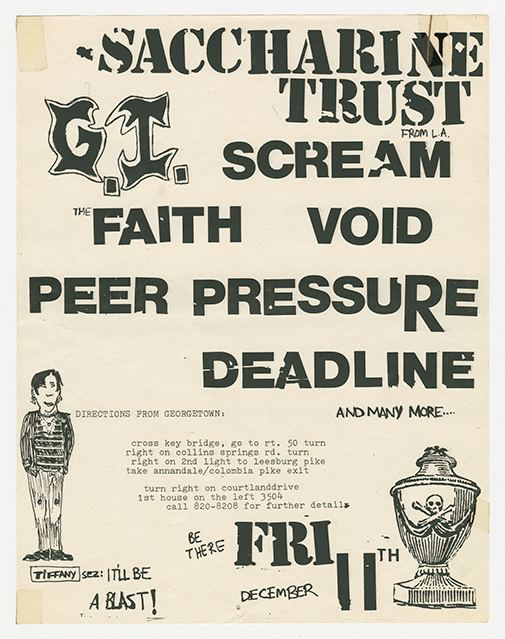

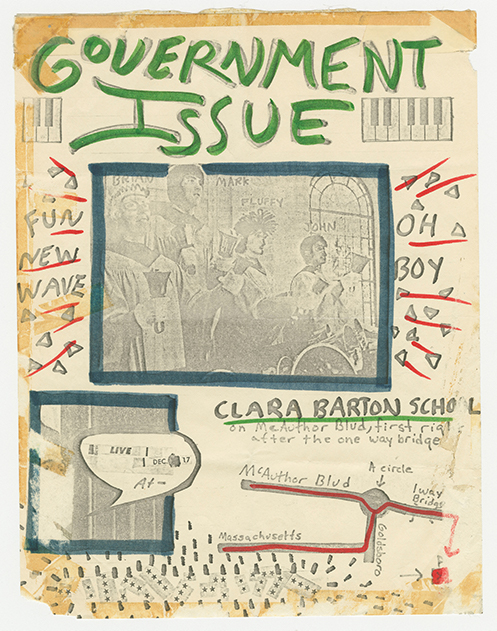

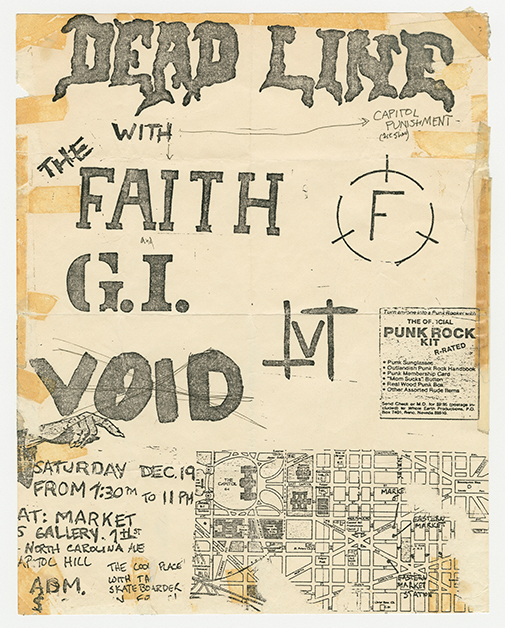

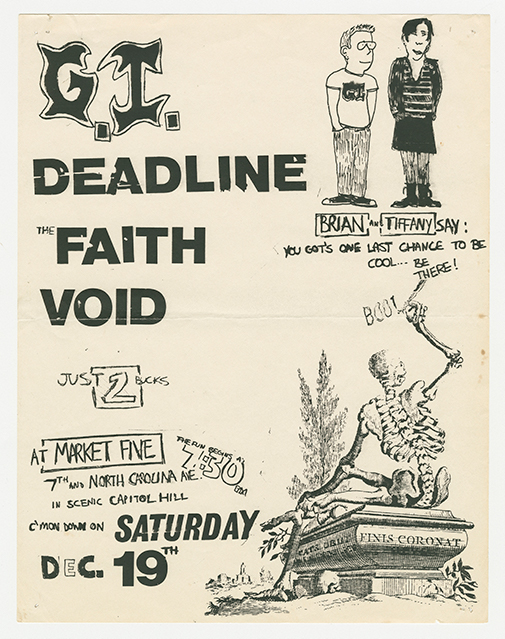

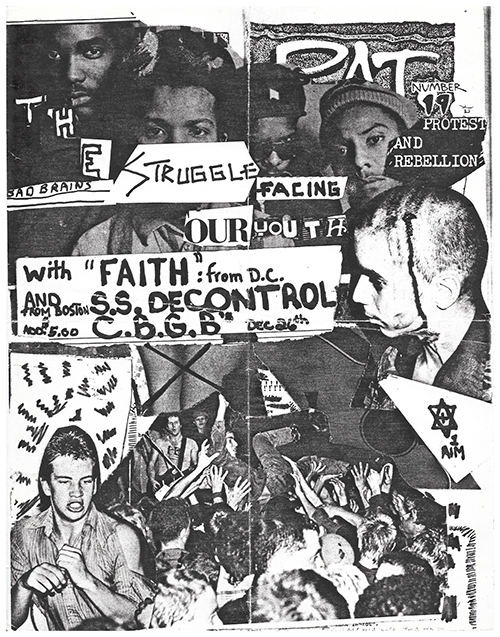

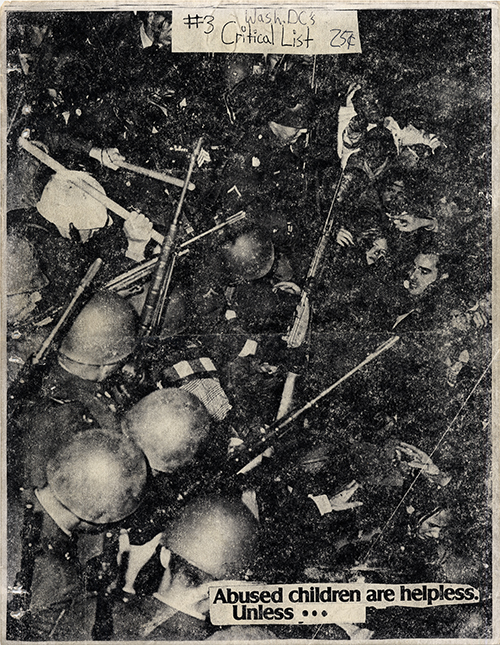

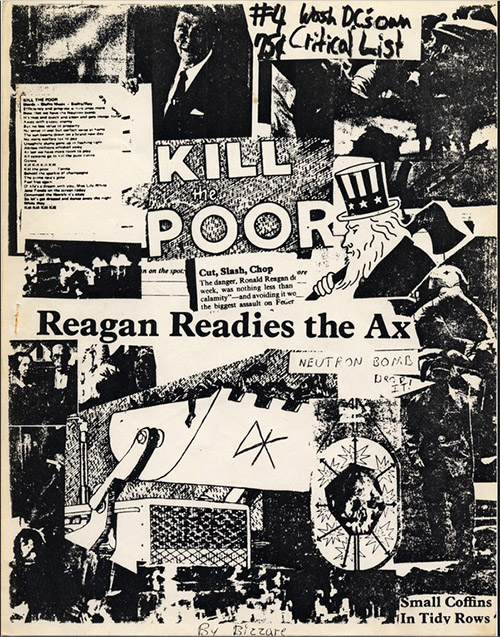

The confrontational positioning and desire for shock extended to the visual media of the year. In fliers, one can see how the designers used photocopiers to recontextualize horrifying images from wartime destruction and militia fighters to racist violence. The latter can be seen in the use of Stanley Forman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph The Soiling of Old Glory (which documented a 1976 incident where a white man used an American Flag to attack Black civil rights attorney Ted Landsmark) as the background image for a show featuring Government Issue, the Faith, and Capitol Punishment.

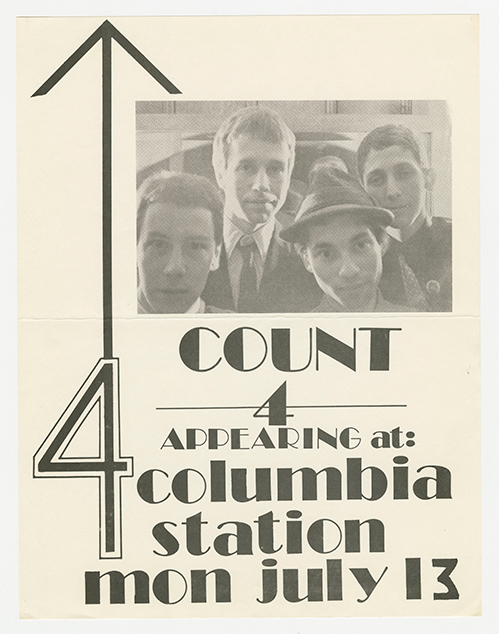

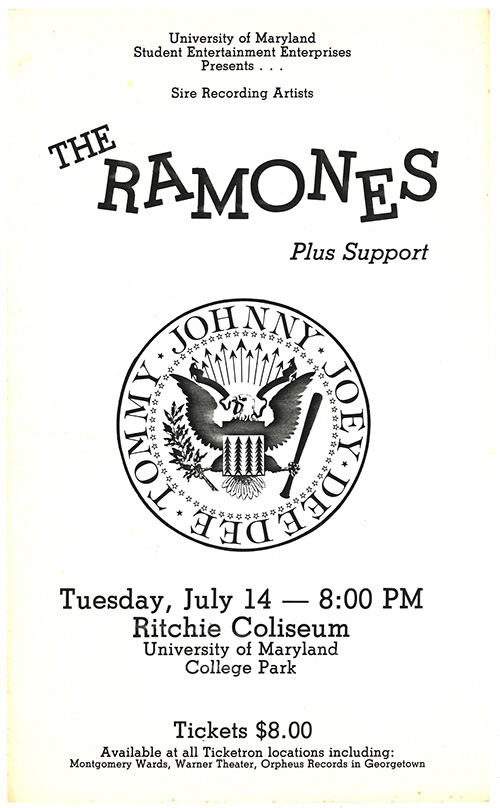

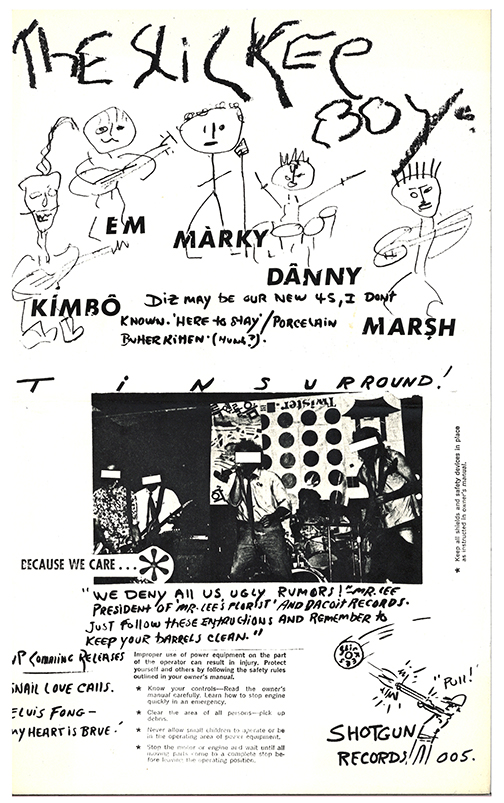

Beyond the attempts to shock, the iconography of the D.C. scene’s new wave took shape more broadly in 1981. Previously, fliers ranged from handbills drawn in marker to newsprint collage posters, and few groups other than the Razz and the Slickee Boys established much of a consistent visual identity. However, in 1981, we see bands establishing a visual identity that can be seen across posters and album art: Minor Threat adopted their jagged hand-lettered logo, the Faith began using a an “F” inside a broken circle as their emblem, and Void used the visual motif of a paired upright and upside-down cross. By the year’s end, the D.C. scene had been almost completely remade from where it was at the end of the 1970s, with a new musical and visual aesthetic in place and set to spread further in the years ahead.

Further Listening

Black Market Baby. "Potential Suicide." Limp Records, 7-inch single.

Government Issue. Legless Bull. Dischord Records, 7-inch EP.

Minor Threat. Minor Threat. Dischord Records, 7-inch EP.

Minor Threat. In My Eyes. Dischord Records, 7-inch EP.

Slickee Boys. "Here to Stay." Dacoit Records, 7-inch single.

State of Alert (S.O.A.). No Policy. Dischord Records, 7-inch EP.

Various. Connected. Limp Records, Album.

Youth Brigade. Possible. Dischord Records, 7-inch EP.

Materials below are drawn from the Paul Bushmiller collection on punk, the Sharon Cheslow punk flyers collection, the Skip Groff papers, and the Robbie White collection on the Slickee Boys.

Tap or hover over an image to learn more.

FLIERS

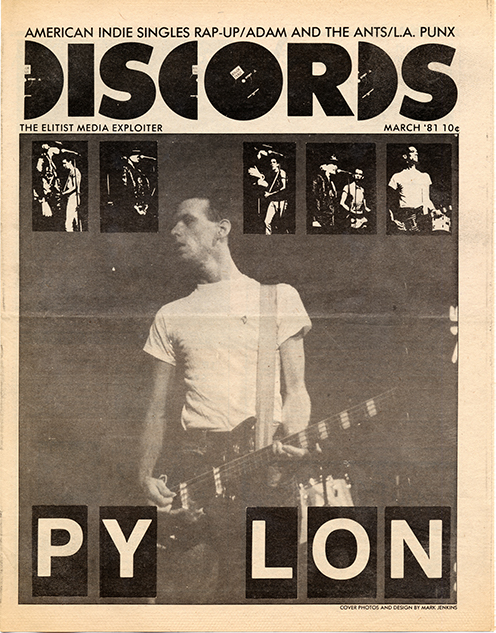

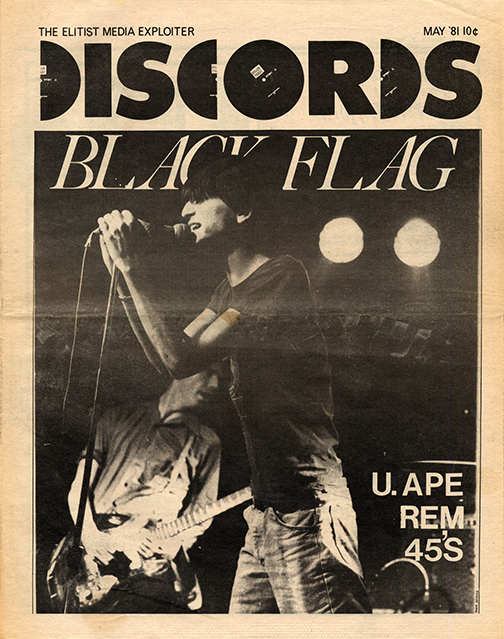

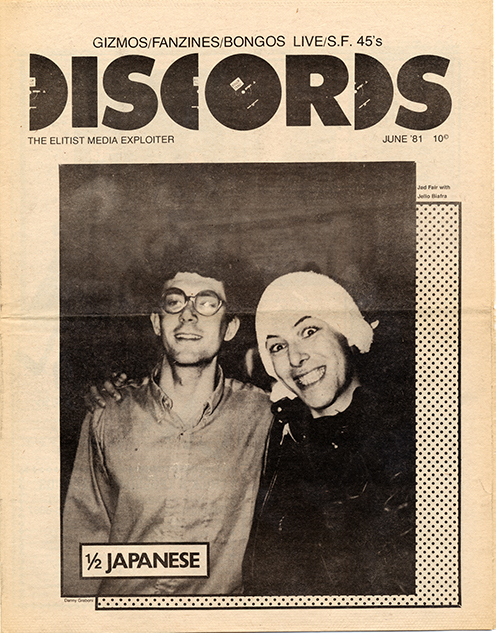

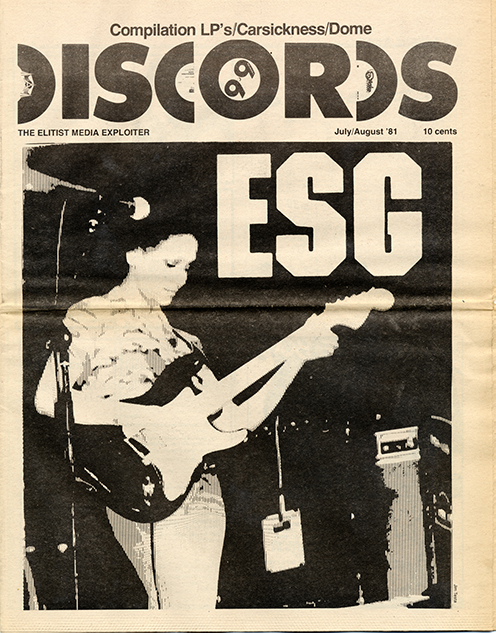

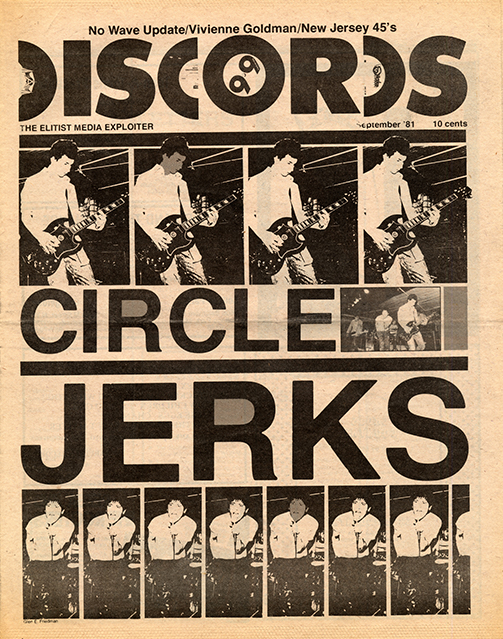

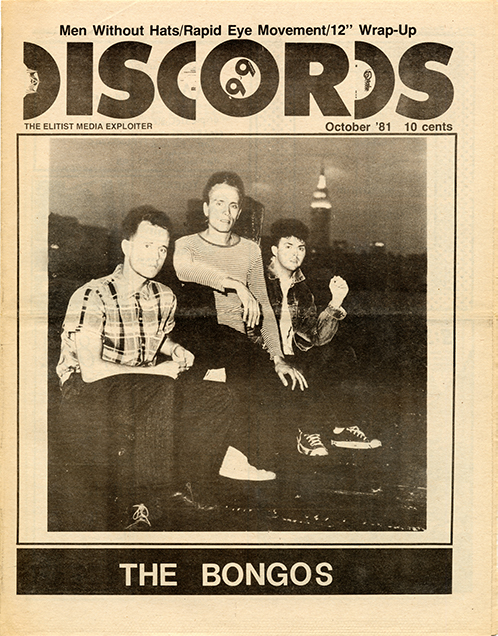

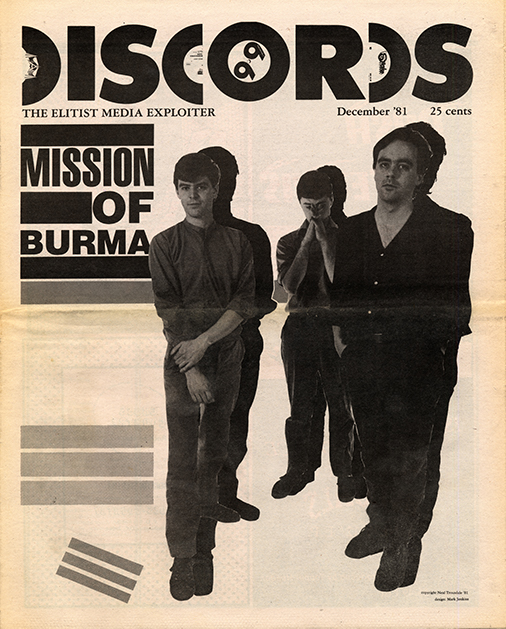

FANZINES

PHOTOGRAPHS

EPHEMERA

RECORDINGS

Tiny Desk Unit, 9:30 Club, Washington, D.C., May 29, 1981

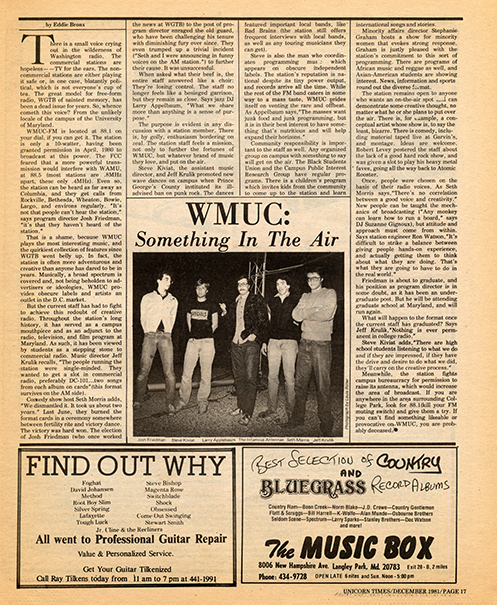

Josh Friedman radio show on WMUC and Tiny Desk Unit interview, 1981

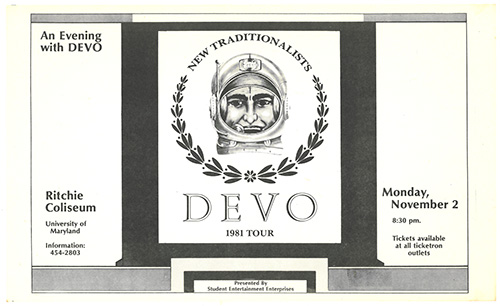

Urban Verbs interview and Devo press conference, 1981

Velvet Monkeys recording, Inner Ear session rough mixes and WHFS interview, 1981

Velvet Monkeys recording, "Everything is Right" alternate sequence, circa 1981