In 1992, D.C. residents, who just two years earlier had watched videotaped footage of then-Mayor Marion Barry’s arrest for drug use in a sting operation, saw him returned to city council. Released from prison in April, Barry wasted no time in filing paperwork to run for the Ward 8 council seat. Using the slogan “He may not be perfect, but he’s perfect for D.C.,” Barry defeated a four-time incumbent in the primary and handily won the general election, returning to governance of the city. Despite Barry’s redemption narrative, the city continued to grapple with the chaos wrought by violent crime and waning public trust in the police force, whom many viewed as incompetent and corrupt.1

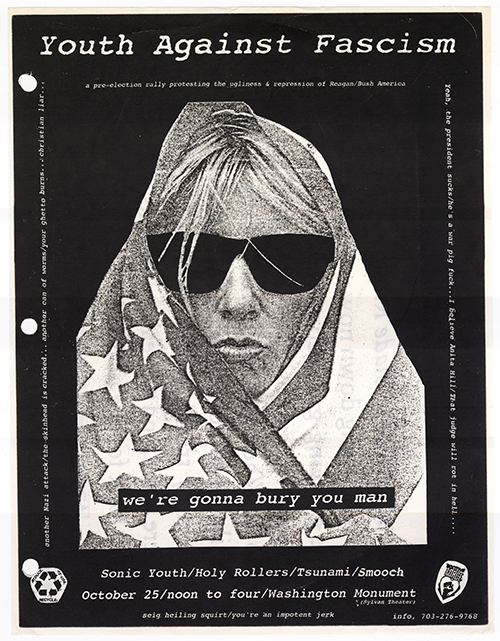

The waning months of 1992 also saw a titanic shift in the national political landscape. President George H.W. Bush lost his bid for re-election to Bill Clinton, a Democrat whose victory exemplified the generational power shift underway as the Baby Boomers wrested the country’s reins from the World War II generation that had been in control for decades. A “cautious centrist” and a skilled populist, Clinton was a symbol of the Democratic party’s shift away from expansive progressive programs and toward a moderate approach to government.2 The Reagan-Bush axis had been the inspiration for so much of what punk protested and its defeat in 1992 seemed to promise significant social change, but a persistent dissonance suffused the punk subculture for the remainder of the 1990s. America’s post-Cold War behavior seemed part victory lap, part disco nap, yet little was different about how the American government treated its constituents or others in the world. This shifted some punks towards cynicism but, for others, the struggle against society’s inequities continued.

In popular music, the year began with Nirvana’s album Nevermind—the Seattle, Washington band’s second album overall and first for the major label DGC—reaching the top spot on the Billboard 200 in January. Nirvana previously recorded for the independent Seattle label Sub Pop and the group’s wild success on DGC, along with the commercial rise of other bands with ties to the punk subculture, led to intense criticism from many within the punk subculture.3

...

Frequently derided as “sellouts” for their role in exposing the punk underground to the mainstream,4 Nirvana would wrestle with the ethics of their move from indie to major label until the group disbanded following the death of guitarist/vocalist Kurt Cobain in 1994. That Nirvana drummer Dave Grohl had been a beloved part of the D.C. scene through bands like Scream, Dain Bramage, and Mission Impossible before he moved to Seattle to join Nirvana in 1990, added a complicated twist to the situation for some D.C. punks.

Although founding groups like the Sex Pistols, the Ramones, and the Clash all recorded for major record labels, punk music had mostly shifted to independent record labels by the early 1980s, solidifying that smaller, anti-corporate approach as part of the genre’s ethos. Punk culture was, in theory, intentionally set apart from the mainstream by its participants. When punk bands left independent labels for major labels, however, the reasons for doing so did not necessarily boil down solely to a desire to be a rock star. Independent labels often struggled to keep up with the needs of their more successful bands, in terms of keeping records in print and providing both promotion and tour support. This often drove groups—some early national examples were the Replacements and Hüsker Dü—toward major labels, which dangled larger operating budgets and promises of creative control in front of musicians who were tired of seeing that their albums were out of stock in record stores. As scholar, musician, and erstwhile D.C. punk Kevin Mattson wrote, “a straight line can be drawn from the signing of Hüsker Dü to Warner Bros. [Records] to [...] the blockbuster success of Nirvana in the early 1990s.”5

When musicians from punk-rooted scenes offered themselves up to the music industry in the early 1990s as it searched for the “next Nirvana,” numerous fans and fanzine editors still viewed it as a betrayal of the subculture’s essence and ethics. The success of Nirvana and the sudden visibility and popularity of the punk subculture in the mainstream also drew countless newcomers to the scene, whom some existing participants viewed cynically as outsiders reacting to a trend rather than genuinely engaging with the tenets of the subculture. This conflict hung over the underground music scene like a pall during the early-to-mid 1990s, although no D.C. punk bands had yet made the leap to a major label in 1992.

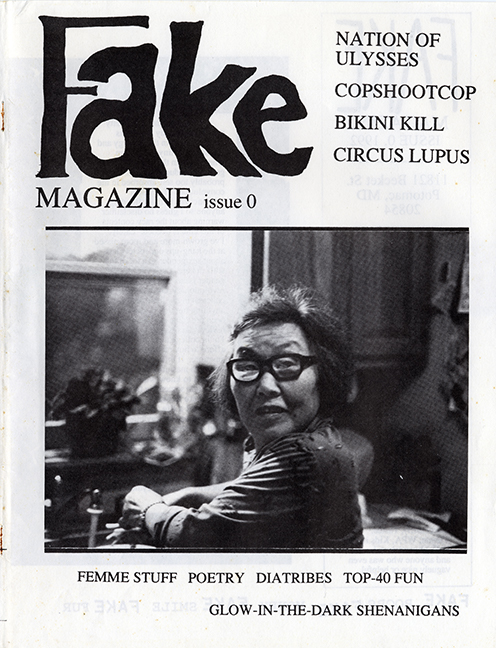

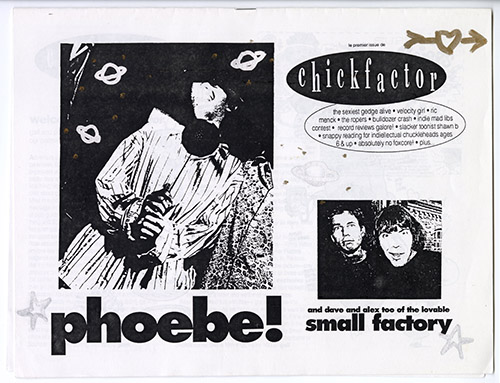

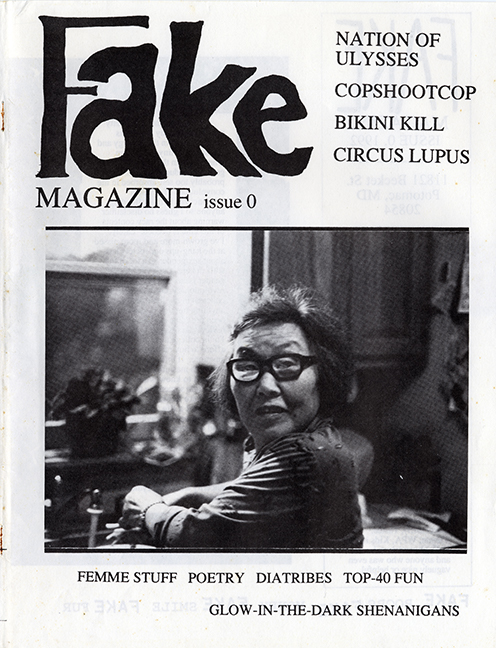

The riot grrrl movement that exploded onto the D.C. scene the previous year continued to produce dynamic new music, performances and organizing. In an interview with Bikini Kill in the zine, Fake, edited and published by Irene Chien, the band is described equally as musical act and political force: "Kathleen encourages girls to be empowered by the d.i.y. attitude. She welcomes the entire crowd with a communal doormat (as opposed to a domestic one), trying to include 'writers, artists and especially 9-to-5 [workers]'." Bikini Kill released an eponymous EP, produced by Ian MacKaye, on Olympia, Washington’s Kill Rock Stars label. The first track, “Double Dare Ya,” used the playground phrase to urge young women to rebel against patriarchal expectations. Meanwhile, Bratmobile toured with Heavens to Betsy for four weeks in June and July, from Olympia down the west coast to San Francisco, across the Midwest, to the Northeast before ending in D.C. for a few more weeks. As more riot grrrl bands appeared, mainstream interest grew, leading to increased media coverage and scrutiny that appeared more interested in the visual presentation of the musicians than in representing their message. Increasingly, members of the foremost groups, including Bikini Kill, refused to engage with the media.6

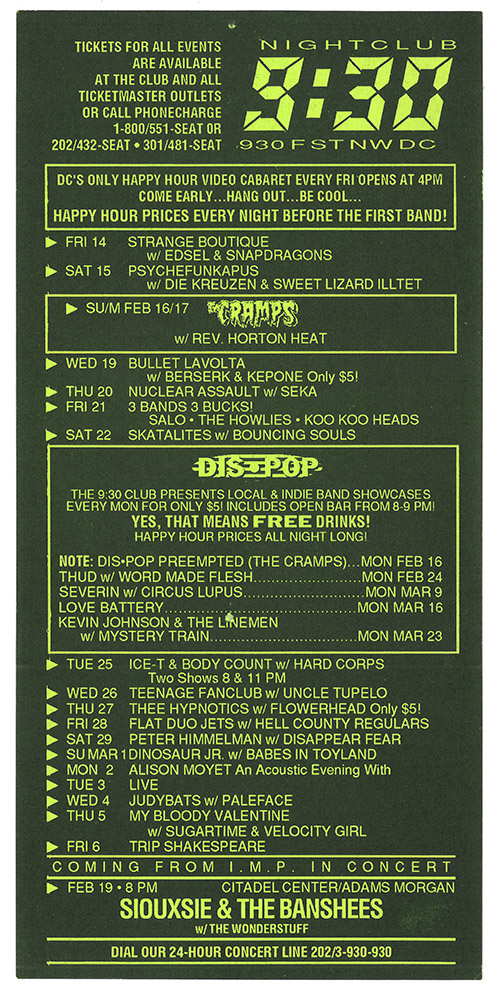

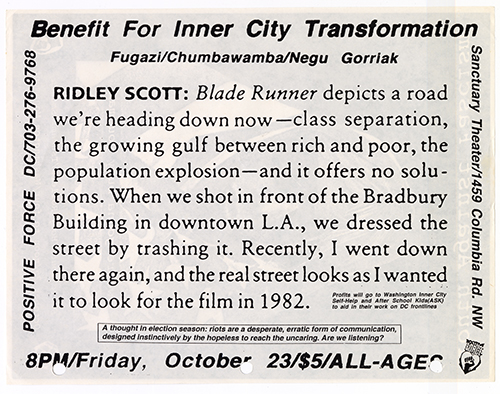

Also in 1992, the right-leaning Supreme Court’s consideration of the constitutionality of a 1982 Pennsylvania state law led pro-choice advocates to fear an overturn of the historic 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling that legalized abortion. Fugazi and Bikini Kill, among others, performed on April 3rd and 4th at the Sanctuary Theater as part of the Rock For Choice series in support of women’s rights, particularly the right to safe and legal abortion. Activism continued into the summer, when Fugazi and Bikini Kill performed on July 25 as part of a protest at the US Capitol Plaza Supreme Court. The concert was punctuated by speakers from various civil rights and equality movements to address the increasing encroachment of the court under the Reagan and Bush administrations.7

The event was somewhat fraught, its momentum stalled by an on-stage electrical outage that forced Fugazi drummer Brendan Canty to play a 4/4 drumbeat on his own for fifteen minutes while the crowd grew restless and technical snafus were sorted. Power was restored but, according to a review in Alternative Press, “Fugazi’s energy was sapped and all the band could manage was a half-hearted, by-the-numbers set.” Despite the hurdles, MacKaye clearly conveyed the urgency of the protest everyone there took part in, asking the crowd: “If today we lose the right to choose, what’s next? The right to vote? [...] [The Supreme Court] may make the rules, but we don’t have to quietly accept them.”8

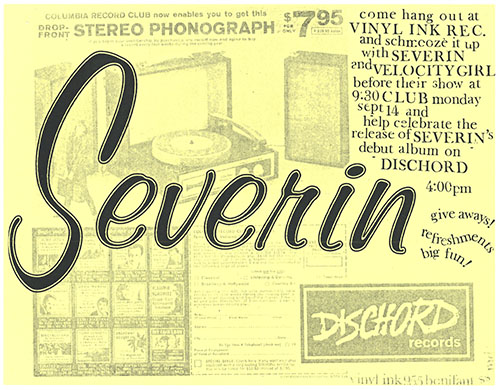

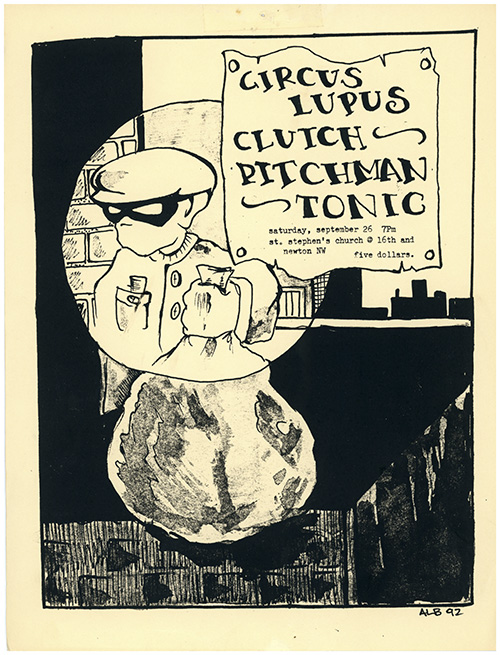

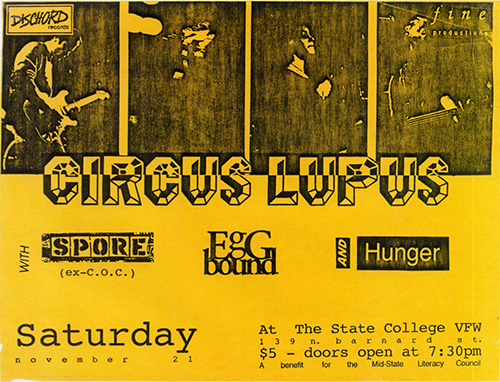

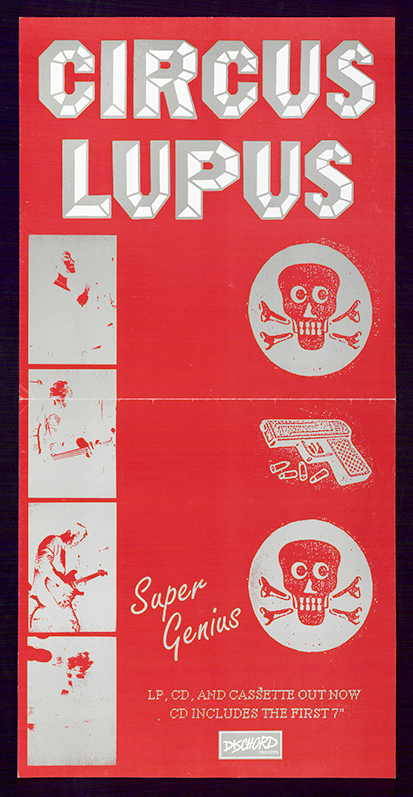

Fugazi did not release any new music in 1992, the first year that had happened since the band’s inception in 1987, but they toured heavily throughout the United States and Europe in support of the previous year’s Steady Diet of Nothing. Dischord Records had another vibrant year in 1992. Severin and Circus Lupus released their debut albums on the label, while Shudder to Think, High Back Chairs, and a reunited Gray Matter also issued new music.

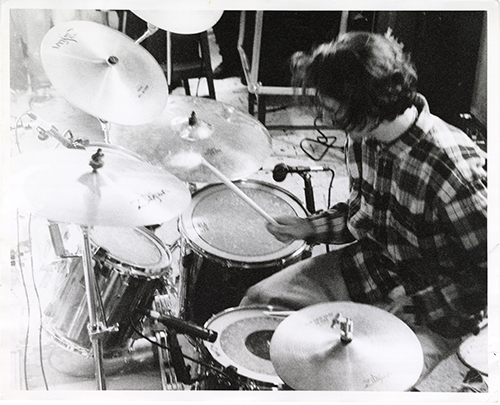

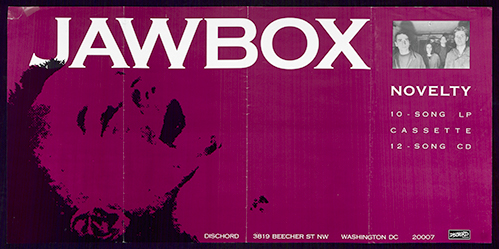

Jawbox and Nation of Ulysses each released their sophomore full-length albums on Dischord in 1992. The former’s Novelty was their first full-length album to feature guitarist/vocalist Bill Barbot, who had joined in 1991 and debuted on the February 1992 single on Dischord, “Tongues” b/w “Ones and Zeroes.” Drummer Adam Wade left Jawbox and joined Shudder to Think, but new drummer Zach Barocas propelled the group with a dexterity and inventiveness that few other punk percussionists could match. Jawbox toured extensively throughout the first half of 1992 before settling in to write the songs that would comprise their next album—a work that would take them through an entirely different side of the music industry.

Nation of Ulysses released Plays Pretty For Baby in 1992 but disbanded that fall. The group’s influence would be notable on punk and indie culture in the years ahead. “It was more the presentation of the Nation of Ulysses that really had an enormous effect on people,” vocalist Ian Svenonius declared later. “In a sense, I feel like the Nation of Ulysses really started a whole entire thing of bands thinking about presenting themselves in another kind of way. [...] I would say our influence, [in terms of] manifestos and band as gang/terror group/political party, was probably most strongly felt through the riot grrrl movement.”9 Nation of Ulysses’ impact on riot grrrl has been acknowledged by several key participants, but other aspects of punk and indie rock cultures would borrow liberally from the Nation of Ulysses’ visual aesthetics and politics. The popular Swedish hardcore group Refused was a particularly egregious example, as were early 2000s indie bands like the Hives and—from a sartorial standpoint—Interpol.

Simple Machines’ release schedule and creative fervor reached new heights in 1992. The Arlington record label tackled numerous projects that came out this year, including another installment in the Machines 7-inch compilation single series (Lever, featuring Severin, Scrawl, Autoclave, and Circus Lupus), a Beat Happening tribute compilation (Fortune Cookie Prize, a benefit that raised more than $15,000 for a nonprofit organization assisting youths experiencing homelessness),10 and the Neapolitan Metropolitan box set that packaged three colorful vinyl singles—with each single compiling four bands from D.C., Baltimore, and Richmond, respectively—with a small, wooden ice cream spatula and a booklet featuring information to raise awareness of fair housing and anti-gentrification activism in the D.C. area. As Toomey and Thomson wrote in the booklet, the activists they highlighted with this project were chosen not only for their noble missions but also because “their creative approaches and motivation to work for lasting change, grounded in a respect for their community.”

The D.C.-themed single in the box set was shared by Bratmobile, Lilys, Whorl, and Late!, the latter being the solo project of Nirvana’s Dave Grohl. Late! was also a part of the Simple Machines’ Tool series, a series of cassette-only releases started in 1992, which were dubbed from the master cassette onto a blank tape as needed to fulfill mail order purchases. Toomey and Thomson viewed the series “as an experiment and as a way we could keep some great music ‘in print’ on an as-needed basis without having to spend a lot of money pressing records or CDs.”11

While releases in the Tool series from lesser known groups like Toomey’s pre-Tsunami band Geek or her side projects Slack (with Dan Littleton of the Hated) and My New Boyfriend, inspired mail orders at a reasonable pace, Grohl’s rising profile led to a persistent demand for Late’s Pocketwatch cassette in the series. When the two original master cassette tapes wore out later in the 1990s from dubbing so many copies, Simple Machines elected to end the entire high-maintenance series. “Cassette was not the right way to put it out,” Pocketwatch co-producer Barrett Jones observed. “It didn’t do it justice.”12 Toomey and Thomson asked Grohl about issuing it on compact disc in the mid-1990s, but he declined. “Dave was more interested in keeping it as a cassette,” they wrote. “So, we have honored his wishes.”13

Teenbeat and Slumberland Records, like their friends at Simple Machines, were at the vanguard of D.C.’s exploding noise pop scene. The record labels reliably issued innovative music that married highly melodic songwriting with punk’s anxious energy and, often, the distorted veil of the shoegazer sound popularized by British acts like My Bloody Valentine. Unrest’s Imperial f.f.r.r. realized the songwriting and instrumental potential that the group had developed in the preceding years, particularly since former Velocity Girl vocalist Bridget Cross joined Unrest on bass in 1991.

As stylistically diverse as Unrest had been since its inception in 1985—its recordings careening between lo-fi indie, hardcore, noise rock, folk, post-punk, and other experiments—the trio settled into its final creative phase at this point, crafting sharp, propulsive pop songs like “Suki” and “Cherry Cream On” that stood among its best work. Co-released by Teenbeat with No. 6 Records in the United States and the venerated 4AD label in the United Kingdom, Imperial f.f.r.r. would be Teenbeat’s highest selling record, according to Robinson. The obfuscations of the music business, however, stood between Unrest and financial reward. “From what I gather it sold a lot, but we didn't get any royalties from it,” he remarked later.14

Velocity Girl also took a giant step forward in 1992 with the release of the “My Forgotten Favorite” single on Slumberland, which presented new singer Sarah Shannon and an even more finely honed songwriting skill. The quintet was relentlessly compared to My Bloody Valentine in its earliest days, but few who listened closely could deny that Velocity Girl had struck upon a uniquely American take on the shoegaze sound, scruffier and more concise in its pop instincts. “We found things like tunefulness, texture, and simple song craft to be almost exotic because of their regional absence,” recalled guitarist Brian Nelson, who joined Velocity Girl in 1991 after stints in Whorl and Black Tambourine. “We wanted to hear hollow-body guitars feeding back open major chords through Fender amps."15

The single on Slumberland gained the notice of Sub Pop Records, who soon signed the band, releasing a split 7” for Velocity Girl and Tsunami through its Singles Club series. The group then went to work on the songs that would make up its debut album, 1993’s Copacetic. “I do think Sub Pop may have changed our outlook on what was possible,” Nelson said. “With a bigger label I think we started to feel like this might be something we could keep doing and even earn some sort of living at, while also being a safe place for us to grow and develop.”16

Black Tambourine, which Nelson and Velocity Girl guitarist Archie Moore had both been members of, had split in 1991, but its second and final 7-inch single was released in 1992 on the Audrey’s Diary label out of Michigan. “Throw Aggi Off the Bridge” presaged the combination of hurtling noise and infectious pop music that Velocity Girl would perfect soon after. Despite its humble discography of just two 7-inch singles, those recordings and a few others were packaged together by Slumberland for 1999’s Complete Recordings compilation (which, ironically, was expanded with several extra tracks and repackaged in 2010 as Black Tambourine). By the 2010s, Black Tambourine had become a notable influence on the noisy brand of indie pop that returned to vogue behind groups like Vivian Girls and the Pains of Being Pure at Heart. “I don't think any of us in the band could've ever imagined that we'd be talking about these songs 20 years after we played them,” Moore remarked later. “There's little information available about Black Tambourine because the story was so short and uneventful. We rehearsed obsessively for a couple of years, played out a few times, and had one recording session.”17

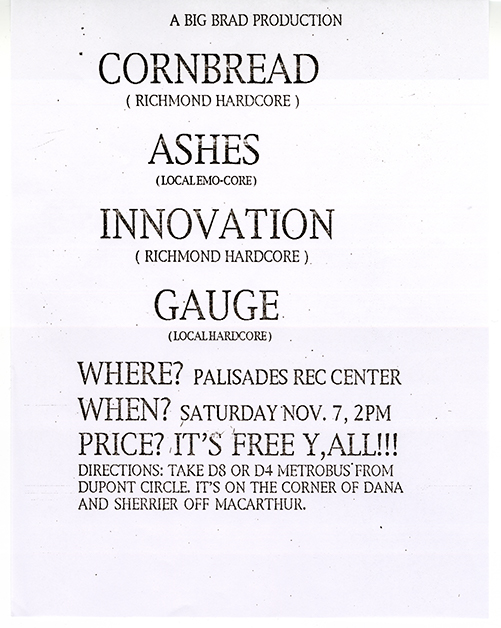

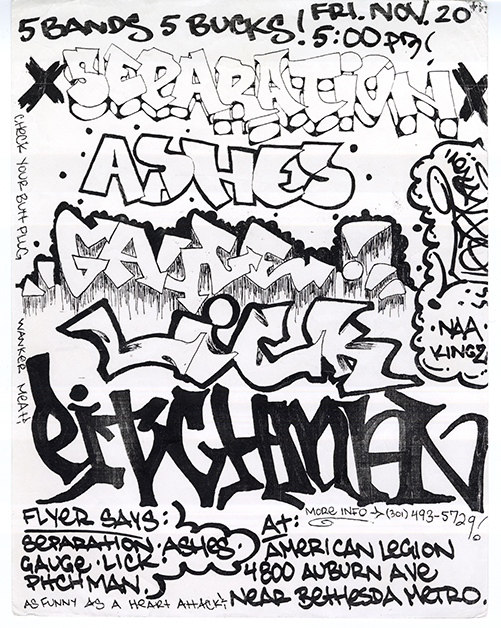

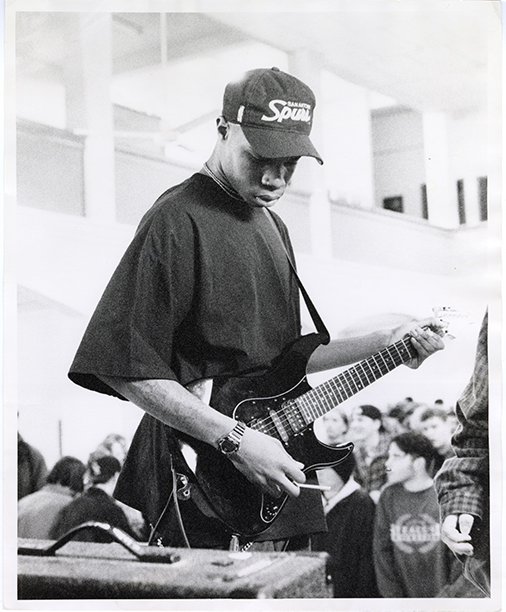

As D.C. punk and indie rock scenes progressed, the city’s hardcore scene also continued the revival that Swiz and the Safari Club had helped spark in the preceding years. A new wave of DC hardcore had developed by the early 1990s, led by Worlds Collide, Battery, Gauge, and several others. This phase of hardcore in D.C. was markedly different than the first wave of D.C. hardcore bands like Bad Brains and Minor Threat in the early 1980s. The two eras overlapped in terms of intensity and aggression, but they diverged in critical ways. The second wave could be notably slower in tempo than the earlier wave and was heavily influenced by thrash metal and the youth crew style of late 1980s hardcore that dominated the New York punk scene. By slightly mixing in the influence of the D.C. post-hardcore sound to craft something new, the result was a crushing, belligerent strain of hardcore that brought a new dimension to the scene in the early 1990s.

The visual aesthetics of the second wave were also distinct from the earlier hardcore scene. Sportswear like hooded sweatshirts, baseball caps, and high-top basketball shoes,18 particularly brands like Champion19 and Nike, were even more central to the clothing styles of early 1990s hardcore, as well as niche accoutrements like the “X” watch produced by Swatch. This signaled a shift away from both the thrift store bricolage and the menacing boots, spikes, and chains style popular in early 1980s hardcore. One style element the first and second wave of D.C. hardcore did share was the employing of large, black “X” markings written on a person’s hands in marker. As with the first wave of D.C. hardcore (and other scenes), many second wave participants used the prominent “X” markings to unmistakably promote their adherence to the straight edge lifestyle of no alcohol, drugs, or promiscuity.

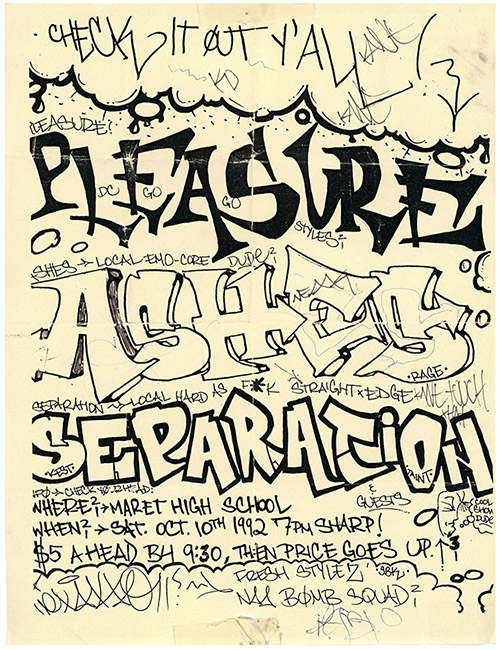

The influence of graffiti and tagging was profound upon early 1990s D.C. hardcore. “Graffiti was a big part of the D.C. hardcore scene’s identity, just like it was for the surrounding scenes on the east coast like Philly and New York,” musician Ben Chused noted. “Most of my friends who went to hardcore shows were [graffiti] writers, it was just what everyone did during that time. Graffiti was all over the place–fliers, zines, records–all around downtown D.C.”20

One of the more intriguing and inventive groups in the new hardcore crop were Ashes, a teenage quartet who stood apart from their musical peers by mixing in more melodic elements. By mingling the mellifluous vocals of Elena Ritchie with the explosive shouts of guitarist Brian McTernan (who also sang for Battery), Ashes straddled several music worlds within the D.C. scene. “My vision for Ashes was to do something that felt like [the hardcore band] Verbal Assault meets [the alternative folk-rock group] 10,000 Maniacs,” McTernan later explained.21 Although Ashes sometimes struggled to find their place in any particular subgenre of the scene, they were most closely associated with the hardcore community and had a large, devoted fanbase.

The common narrative of Washington, D.C. in 1992 is that it was a place racked by violence, drug abuse, corruption, and political tumult. The city’s murder rate dipped just below the previous year’s record high but it would still be a few more years before the rate declined steadily enough in the mid-1990s to indicate that the change would be consistent. D.C.’s bleak reputation was understandable but the city was still a place of renewal, hope, activism, and beauty. Amid shifting cultural and political landscapes, D.C. area residents refused to define their home by a reductive view of its most daunting challenges. The D.C. punk subculture was just one small part of the city’s mosaic, but in 1992—like the years before and those to come—its thriving climate of creativity and protest was testament to the tenacious belief that many of the area’s residents had in the possibilities of change and the promise of community.

Further Listening

Ashes. Serenade. self-released cassette demo.

Autoclave. Autoclave. Dischord Records/Mira Records, 10-inch EP.

Bells Of. 11:11. Teenbeat Records, album.

Bikini Kill. Bikini Kill. Kill Rock Stars, 12-inch EP.

Bikini Kill/Huggy Bear. Yeah Yeah Yeah Yeah/Our Troubled Youth. Kill Rock Stars, split album.

Black Tambourine. Throw Aggi Off the Bridge. Audrey's Diary, 7-inch EP.

Bratmobile. Kiss and Ride. Homestead Records, 7-inch EP.

Bratmobile/Heavens to Betsy. K Records, split 7-inch single.

Circus Lupus. Super Genius. Dischord Records, album.

Circus Lupus/Trenchmouth. Skene! Records, split 7-inch single.

Edsel. Strange Loop. Merkin Records, album.

Eggs. Bruiser. Teen-Beat Records, album.

Fine Day. “Extinct”/”Soot.” Sunspot Records, 7-inch single.

Fly. We Know. Sunspot Records, 7-inch EP.

Geek. Hammer. Simple Machines (Tool cassette series), album.

Gray Matter. Thog. Dischord Records, album.

Grenadine. Goya. Shimmy Disc/Teen-Beat, album.

High-Back Chairs. Curiosity and Relief. Dischord Records, EP.

Jawbox. "Tongues"/"Ones and Zeroes." Dischord Records, 7-inch single.

Jawbox. Novelty. Dischord Records, album.

Manifesto. Manifesto. Fire Records, album.

The Nation of Ulysses. Plays Pretty For Baby. Dischord Records, album.

Pitchblende. “Sum”/”Lacquer Box.” Land Speed, 7-inch single.

Pitchblende. Weed Slam. Jade Tree, 7-inch EP.

Severin. Acid to Ashes Rust to Dust. Dischord Records, album.

Severin. Smash Hits. Superbad Records/Dischord Records, 7-inch single.

Shudder to Think. Get Your Goat. Dischord Records, album.

Shudder to Think. Hit Liquor. Dischord Records, 7-inch single.

Suture. Suture! Dischord Records/Decomposition Records, 7-inch EP.

Swiz. With Dave Jade Tree, 7-inch single.

Tsunami. Geniuses of Crack. Homestead Records, 7-inch single.

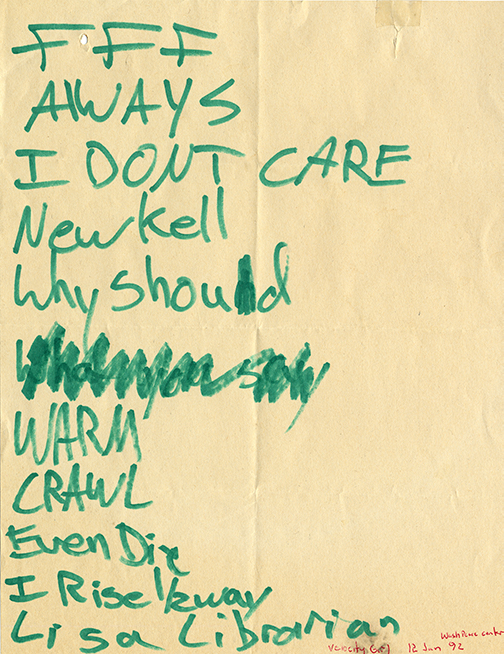

Tsunami and Velocity Girl. “Left Behind/Warm/Crawl.” Sub Pop Records, 7-inch single.

Unrest. Imperial f.f.r.r. Teen-Beat/No. 6 Records/4AD, album.

Various. The Embassy Tapes 1990-1992. Compilation cassette.

Various. Fortune Cookie Prize. Simple Machines, compilation LP.

Various. Go in the Dark. Mira Records, compilation 7-inch EP.

Various. Neapolitan Metropolitan. Simple Machines, compilation 7-inch box set.

Velocity Girl. My Forgotten Favorite. Slumberland Records, 7-inch single.

Velocity Girl and Tsunami. Season’s Greetings. Simple Machines, split 7-inch single.

Wingtip Sloat. Half Past I’ve Got. VHF Records/Sweet Portable Junket, double 7-inch album.

Worlds Collide. Worlds Collide. Victory Records, 7-inch single.

Materials are drawn from the Chris Baronner digital collection on D.C. punk, the D.C. punk collection, the Paul Bushmiller collection on punk, and the Aaron Claxton collection on D.C. Hardcore.

Tap or hover over an image to learn more.

FLIERS

ZINES

PHOTOS

EPHEMERA

VIDEO