In 1987, both local and national scandals mounted in The District. The American news cycle was absorbed for the better part of the year with the findings of the Tower Commission on the Iran-Contra Affair.1 The report outlined the negligence of the Reagan administration in its flouting of international law by selling arms to Iran in the midst of the Iran-Iraq war. An appendix to the report encapsulated the implications of the dealings, opening with a quote from the Roman poet Juvenal, “quis custodies ipsos custodes” or “who watches the watchers?”2

Locally, a number of major issues gripped Washington. A blizzard brought service interruptions to the Metro subway system and dozens of buses, stranding commuters across the city. While the storm wreaked havoc, Mayor Marion Barry was in California on a pre-planned trip to attend the Super Bowl and make political appearances. His absence turned into a minor scandal for the increasingly beleaguered mayor, who was attempting to fight off the explosion in drug trafficking in D.C.3 Later in the year, Washington, D.C. became the city with the most murders per capita in the country in cities with more than 400,000 residents, earning the unwelcome title of "murder capital." The insinuation that the nation’s capital was crime-ridden was, by 1987, a well-worn trope, but the moniker proved hard to escape.4 As the murder spike continued in the coming years, it became evident that the violence in the city disproportionately affected those who had been continually hardest hit by the city’s tumult, working class people of color.5

...

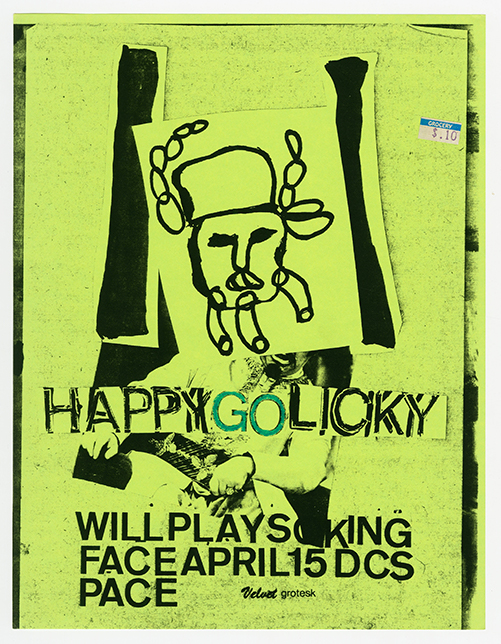

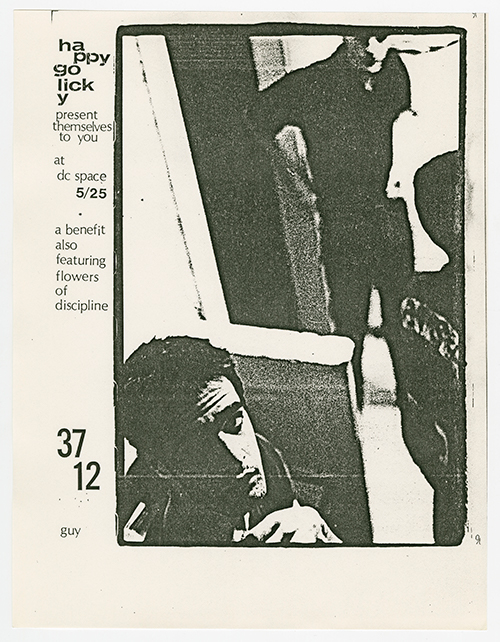

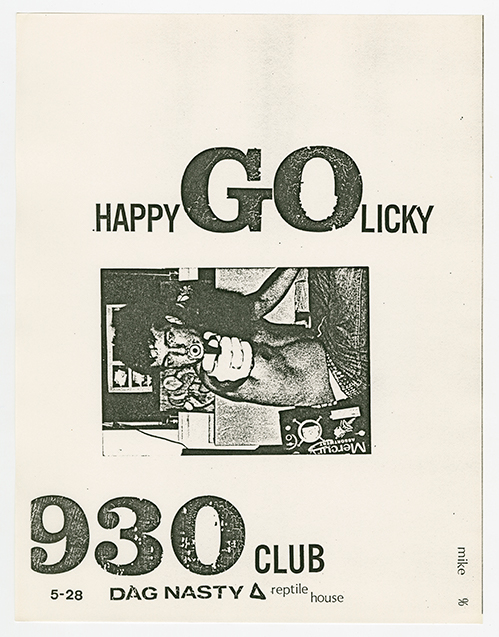

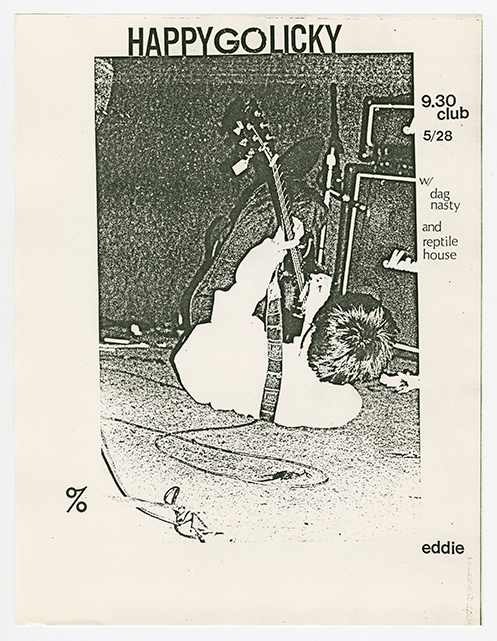

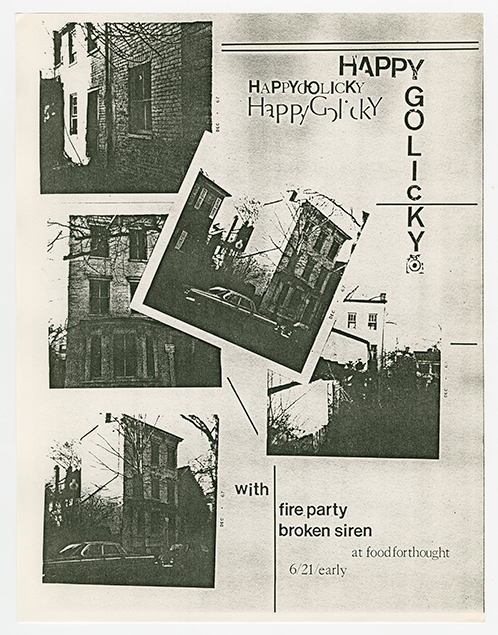

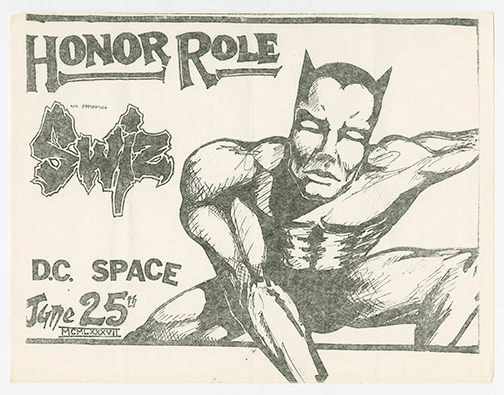

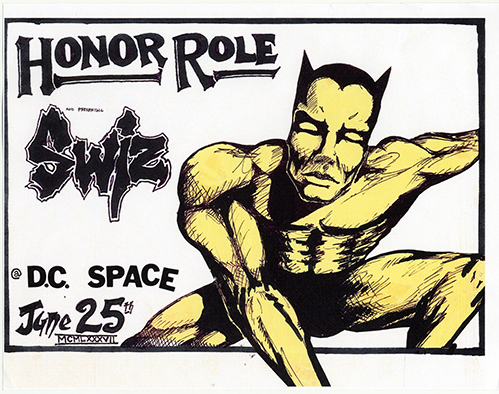

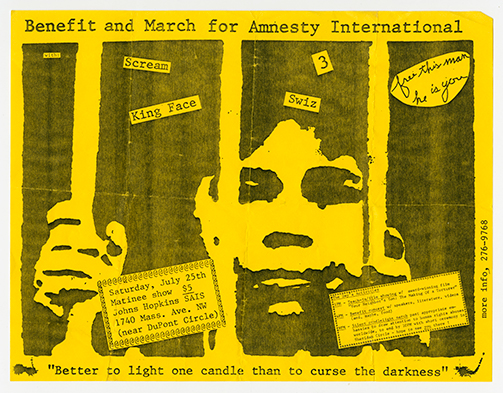

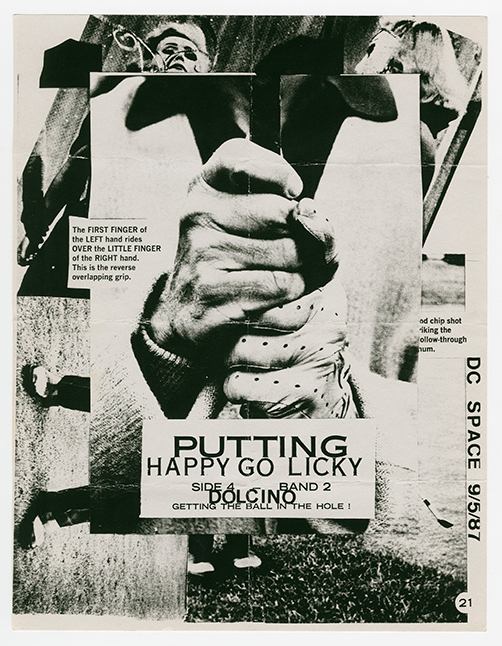

With the dissolution of many Revolution Summer acts in 1986, the local scene began to move forward again in 1987. Former Dag Nasty vocalist Shawn Brown formed one of the new stalwarts of the scene, Swiz, alongside guitarist Jason Farrell, bassist Nathan Larson, and drummer Alex Daniels. "We felt the direction of [D.C.] music changing, but we were all into hardcore punk," Brown recalled. "That was our aesthetic. We were the hardcore band that thought its mission at the time was to 'keep it real.'"6 Other musicians sought to make something new out of the fallout from the two previous years. All four former members of Rites of Spring reunited in 1987 with a vastly different project, Happy Go Licky, which embraced more experimental and improvisational approaches.7

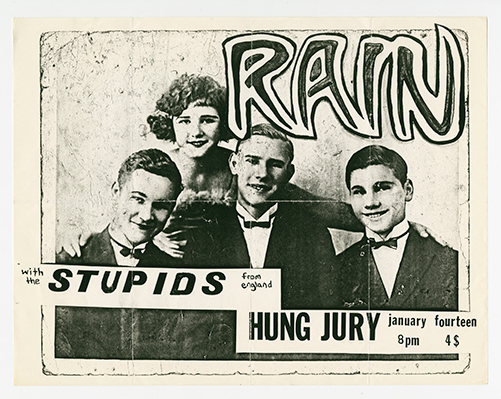

Rain was another new presence in the scene in 1987 but, unlike Swiz, their sound was a direct continuation of the melodic, introspective punk of the Revolution Summer bands. Rites of Spring and Gray Matter were obvious touchstones, but the band—guitarist/vocalist Jon Kirschten, guitarist/vocalist Scott McCloud, bassist Bert Queiroz, and drummer Eli Janney—was no clone. Songs like “Worlds at War” and “That Time of Year” stood alongside the best of their peers, but the group was not to release any music during its brief lifetime. If they resembled the Revolution Summer bands, it was in the brevity of their existence, splitting up before 1987 was out. The recordings they made that year were released in 1990 as the La Vache Qui Rit EP on Peterbilt Records.

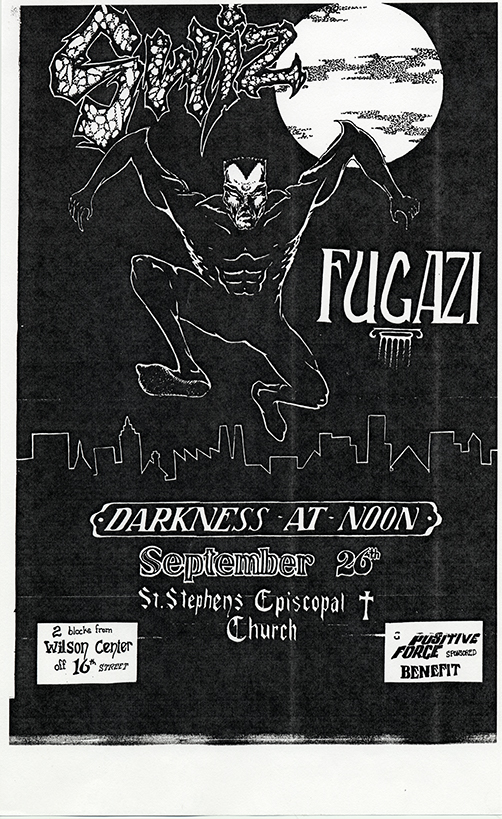

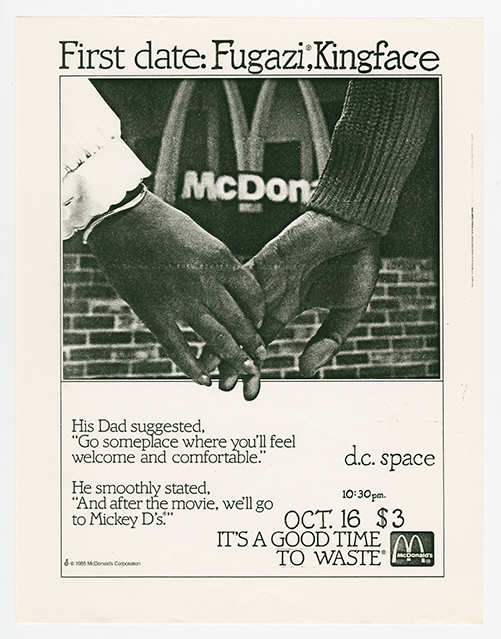

One of the most influential bands to come out of the D.C. scene made its public debut at the Wilson Center on September 3rd, sharing the bill with Marginal Man, Ignition, and Fire Party. Fugazi was a new project featuring vocalist/guitarist Ian MacKaye, bassist Joe Lally and former Rites of Spring drummer Brendan Canty and vocalist/guitarist Guy Picciotto. The band's music was a fervent blend of punk energy, melodic songwriting, and dub reggae-inspired rhythms. Fugazi’s lyrics were as intimate as they were confrontational, continuing the Revolution Summer ethic of seeking to critique and transform one's internal and external worlds. Almost immediately, Fugazi's popularity would exceed that of any other D.C. punk band, taking the group around the world and into larger venues within a few years.

Three was another D.C. band that performed often in 1987 at venues like Food For Thought and the Wilson Center. Geoff Turner, Steve Niles, and Mark Haggerty of Gray Matter joined with Jeff Nelson of Minor Threat to launch a band that took the D.C. scene even further into melodic territory. The band’s lone album, Dark Days Coming, would not see release until 1989, well after their breakup. The band’s final concert, alongside Happy Go Licky (who also gave their farewell performance) and Bastro, occurred on January 1, 1988 at the 9:30 Club. Three left behind powerfully anthemic songs like “Swann Street,” “Don’t Walk Away,” and “International,” incorporating sophisticated songwriting and backing vocal arrangements that innovated post-hardcore and power pop in equal measure.

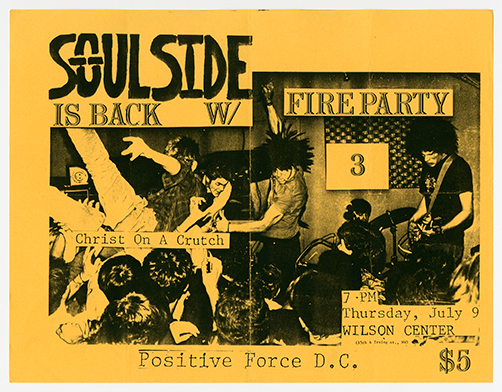

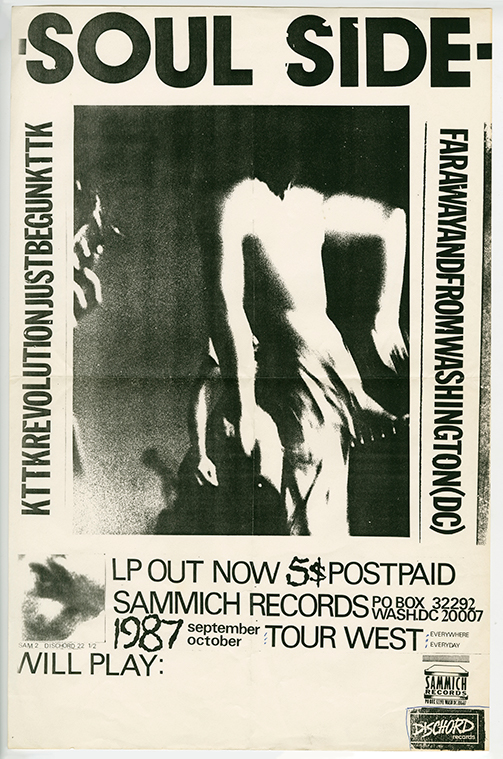

As those new bands honed their sounds, the records released by D.C. bands in 1987 highlight just how many different approaches had already been pursued, as the scene had long since broadened beyond hardcore. Soulside was a reincarnated version of the Revolution Summer band Lünchmeat, whose members—Alexis Fleisig, Scott McCloud, Bobby Sullivan, and Chris Thomson—had gone off to college, but soon reformed under the new name. Soulside’s debut album Less Deep Inside Keeps featured a wide palate of textures from layering electric and acoustic guitars on “Dreams” to the more orthodox hardcore influence heard on “Pearl to Stone.”8

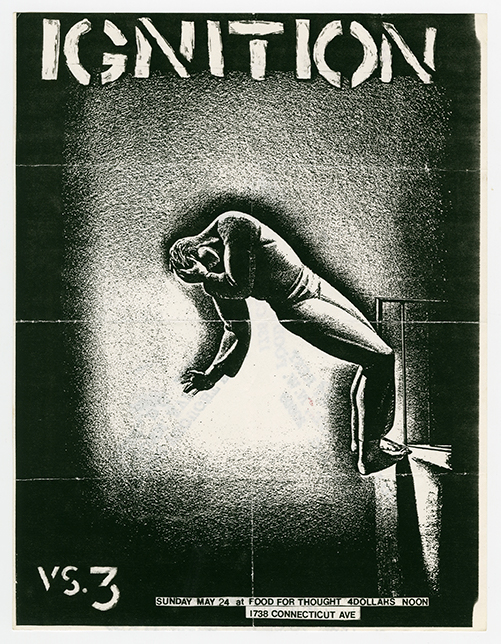

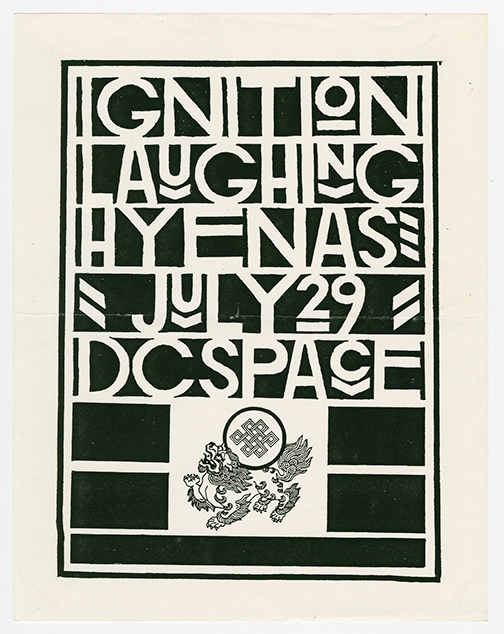

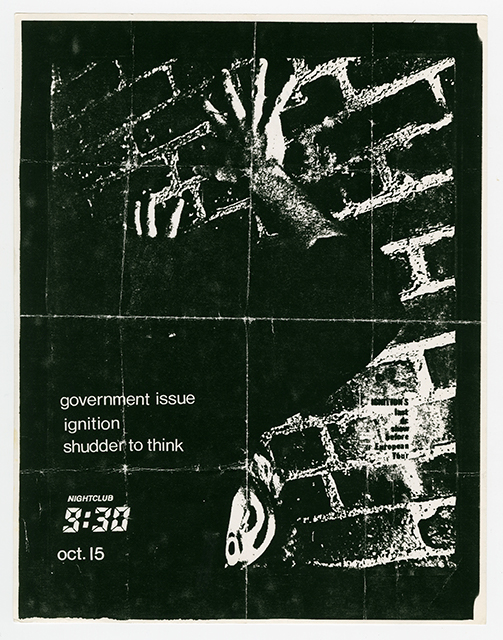

Thomson also played bass in Ignition, a new band featuring drummer Dante Ferrando (late of Gray Matter) and reunited vocalist Alec MacKaye and guitarist Chris Bald, who had last collaborated in the Faith. The group released a pair of 7-inch records in 1987 on their own IG label, the latter a co-release with Dischord. Ignition’s musical variety was intriguing, with the slow burn of “Sinker” a captivating complement to the rousing “Proven Hollow.” “It was a very different type of band,” Ferrando recalled. “We were a lot more chaotic than other bands. [...] We were very angry people and a little bit crazy, at that time period. All of us were in weird states of mind.”9 Bald’s cover artwork on the two singles was an extension of the moody, evocative aesthetic of his former band, Embrace—whose posthumous album was released by Dischord in 1987. Hints of the Constructivist and Expressionist art movements are evident in the angular, melancholy graphics of the Ignition singles, yet the style feels unique. Ripe with mystery and shadow, the art immediately provided Ignition with a distinctive visual identity.

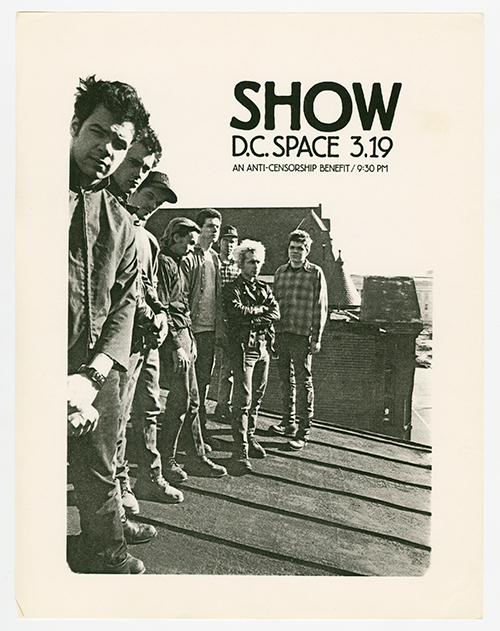

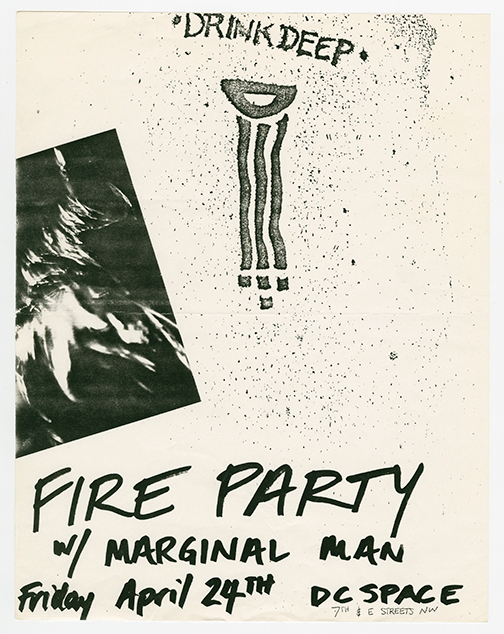

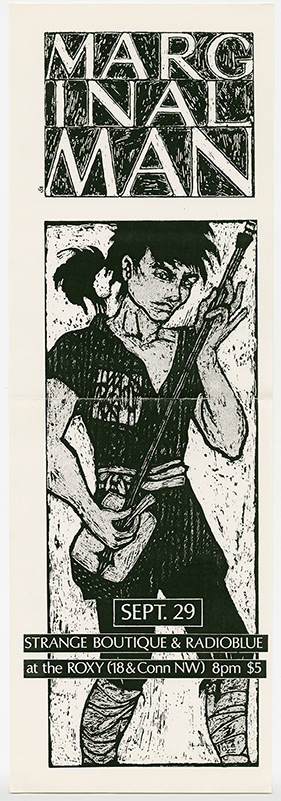

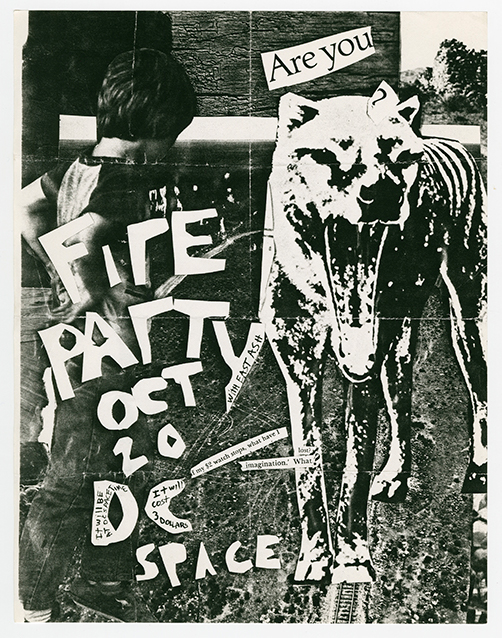

Fire Party made its live debut on April 24 at dc space, opening for Marginal Man. Vocalist Amy Pickering, who helped inspire the Revolution Summer movement with the cryptic messages she mailed to fellow scene participants in 1985, now fronted her own band, which included guitarist Natalie Avery, bassist Kate Samworth, and drummer Nicky Thomas. Pickering described feeling extremely nervous before the band’s first concert. In addition to the usual first show jitters, Fire Party stood out by having all female members, which was still a rarity in punk. “Even though I was surrounded by my friends, I was really scared,” she said. “After we got off the stage, people were so kind to us. And I never really had to worry about [being nervous] again.”10 The group’s music was guitar-driven like several of their peer bands in the scene, full of intensity and nuance, but stood alone in its sound thanks to the group’s musical chemistry and Pickering’s fierce, open vocals.

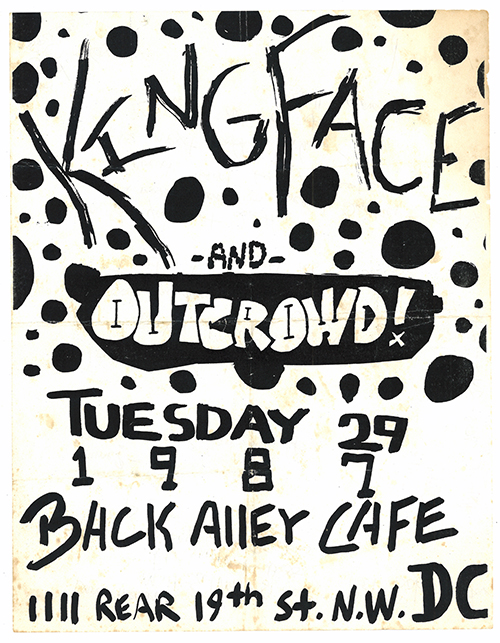

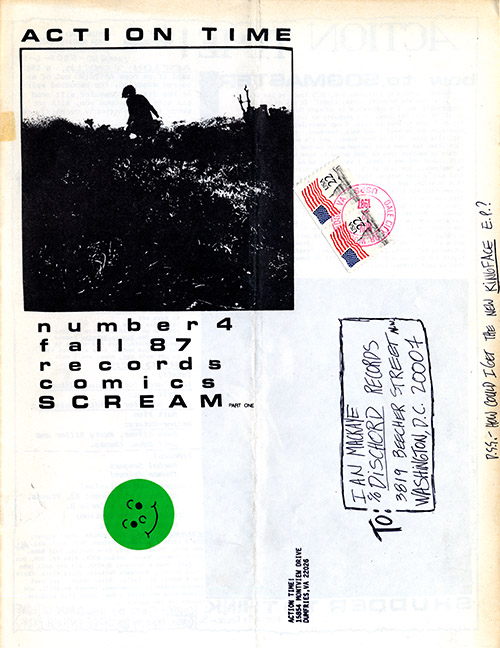

King Face had been on the scene for three years before releasing their debut eponymous EP in 1987. Led by singer Mark Sullivan, King Face brought a traditional hard rock sound to the scene that was often, on the surface, incongruous with their more politically-minded partners in the punk community. Sullivan had come out of the hardcore scene (he had accompanied the Teen Idles on their transformative cross-country trip in 1980), resided at Dischord House, and his brother, Bobby, was the vocalist for Soulside. Those bonds helped make King Face an integral part of the D.C. punk scene, though few, if any, other bands in the community offered up straight-faced classic rock covers like King Face occasionally did. “If I hadn’t lived at Dischord House, there’s no way we would’ve played the kind of shows we did,” Sullivan explained. “We were a feel-good rock band. I wanted people to come to my show and feel great.”11 There was far more to the music that just id, however, as Ignition vocalist Alec MacKaye testified. “Mark’s lyric writing was amazing,” he said. “He’s a deep thinker. It was like he was writing from a college text or something. They were mighty.”12 Indeed, Sullivan would go on to publish his first novel in 2003, Jonah Sees Ghosts, which Library Journal observed was “written with insight and compassion.”13

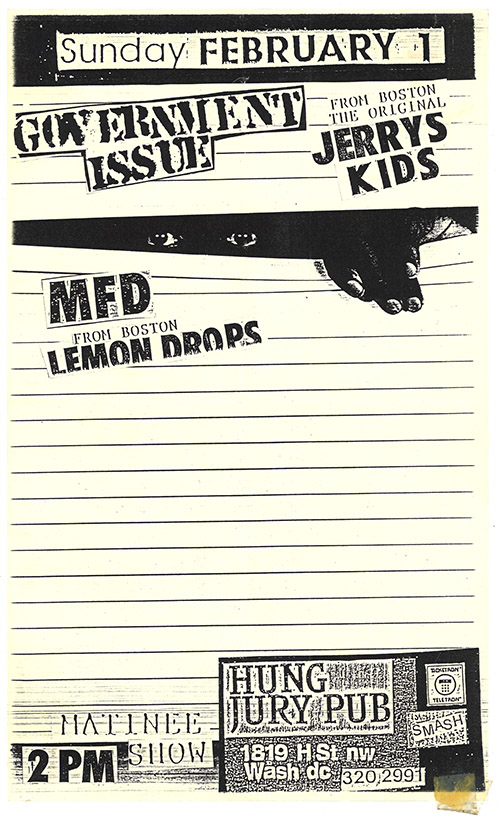

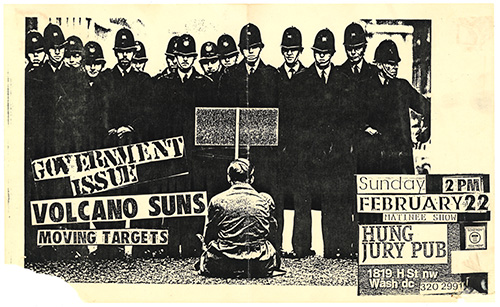

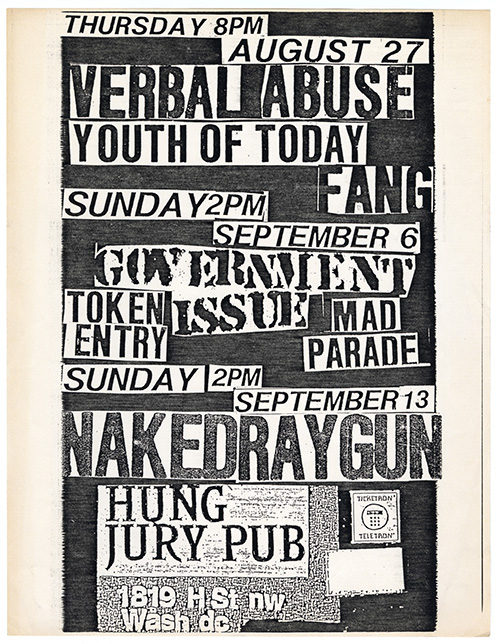

The two most accomplished recordings released this year out of the D.C. punk scene were from familiar faces. Government Issue reached their creative peak around this time, issuing the You album on Giant, an independent label from New York that ultimately collaborated with several bands from the D.C. scene. Government Issue’s songwriting had progressed greatly since its early days, which was never more evident than on the powerful album-opener, “Jaded Eyes.” Vocalist John Stabb and longtime guitarist Tom Lyle now had an extraordinary rhythm section to work with in bassist J. Robbins (who then went by Jay Robbins) and drummer Pete Moffett. The group continued to tour heavily, but its days were numbered.

Dag Nasty, too, had recently reconfigured its lineup. The band’s second album, Wig Out at Denkos, was released by Dischord in 1987, but only guitarist Brian Baker and drummer Colin Sears remained from the original lineup. Dave Smalley, who had initially replaced Shawn Brown as vocalist, departed the band and was replaced by Peter Cortner. Bassist Roger Marbury, who had collaborated with Sears back in Bloody Mannequin Orchestra, was also out, and former Descendents bassist Doug Carrion was in. Cortner’s vocals were far more melodic than the strained bark that Smalley employed on Dag Nasty’s previous album, Can I Say. Likewise, the songs on Wig Out at Denkos had an additional melodic punch, with “Safe,” “Trying,” “The Godfather,” and “Simple Minds” standing out among an outstanding crop of songs that merged pop and hardcore seemingly effortlessly.

Soon after, Sears was replaced on drums due to an injury and, along with new drummer Scott Garrett, Dag Nasty moved its home to Los Angeles. The band’s sound, as heard on the All Ages Show single released in the fall—their debut release for Giant Records—soon changed drastically, toward a more heavily produced, ostensibly mainstream rock style of production that alienated some older fans. The title track, an otherwise rousing blast of pop-punk, was slathered in the sort of studio effects that were on trend at the time, but have aged poorly. “It makes everything they did before a complete lie,” declared Ignition’s Chris Bald.14

The fourth wave of the D.C. punk scene had arrived by 1987, with new bands building off of what came before to create a new sound that would be just as defining for the city’s subculture as ones that came before. Refusing to never be defined by one act, sound, or person, the latter half of the 1980s demonstrated the resilience of punk in D.C.

Further Listening

Dag Nasty. Wig Out at Denkos. Dischord Records, Album.

Embrace. Embrace. Dischord Records, Album.

Government Issue. You. Giant Records, Album.

Ignition. Ignition. IG, 7-inch EP.

Scream. Banging the Drum. Dischord Records, Album.

Soulside. Less Deep Inside Keeps. Sammich Records/Dischord Records, Album.

Swiz. Down. Hellfire, 7-inch EP.

King Face. King Face. King Face, KF-1, 1987, EP.

Materials are drawn from the Paul Bushmiller collection on punk, the Sharon Cheslow punk flyers collection, and the Jason Farrell collection.

Tap or hover over an image to learn more.

FLIERS

ZINES

EPHEMERA