Washington, D.C. in 1993 was, as ever, a site of change. On the national level, President Bill Clinton was sworn in that January, concluding the twelve-year reign of Ronald Reagan and his Republican successor George H.W. Bush. The election of the moderate liberal Clinton gave hope to many participants in the punk scene, and elsewhere, that the progressive ideas seeded during the Reagan-Bush era might finally grow into something tangible as the nineties moved forward. That summer, Clinton nominated Ruth Bader Ginsburg to the United States Supreme Court who, following her confirmation, grew into a liberal icon by the time of her death in 2020.1

There was a sense that the District itself had been on the ballot in the year prior, but the push and pull on key issues of spending, statehood, and violence kept D.C. in a holding pattern. Clinton had ran on a campaign to shrink government spending, promising to slash the federal budget deficit by half.2 However, Federal and local government had long been a steadfast arena of employment for D.C.’s residents, and the threat of lost jobs was leading to a growing fear that there would be a mass exodus due to government budget cuts.3 Indeed, more residents continued moving out of the District in 1993. Its total population dipped below 600,000 that year, steadily continuing its decline from a peak of more than 800,000 in 1950.4 The “for sale” signs that became commonplace in many residential neighborhoods would become the harbingers of the gentrification that marked the coming decades.5

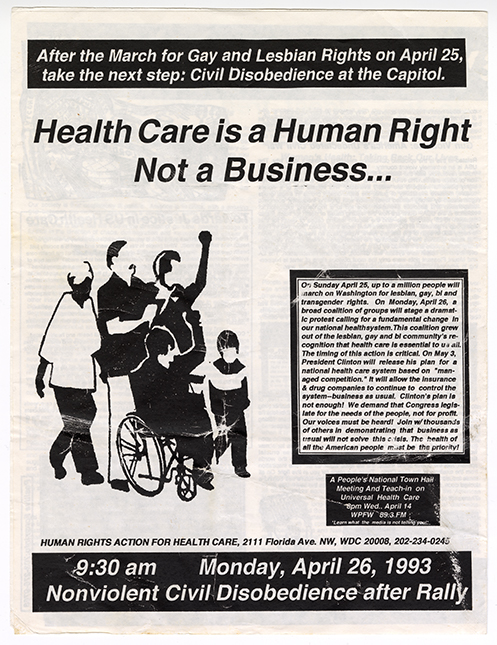

D.C.’s fight for statehood was renewed and persistent in 1993, with Senators Edward Kennedy and Paul Simon sponsoring a bill to make the District of Columbia the 51st state, as the two had done in the two preceding congresses.6 Mayor Kelly saw statehood as an attainable goal, and quickly made this fight a defining element of the year, including her own arrest during a protest for statehood.7 However, as Kelly returned again and again to the issue of statehood when pressed about the continually trying issues of migration out of the district, loss of jobs, an ill-supported police force, persistent violence, and a new peak for the District’s murder rate, some pointed to the statehood argument as a deflection from the longstanding issues affecting Washingtonians.

...

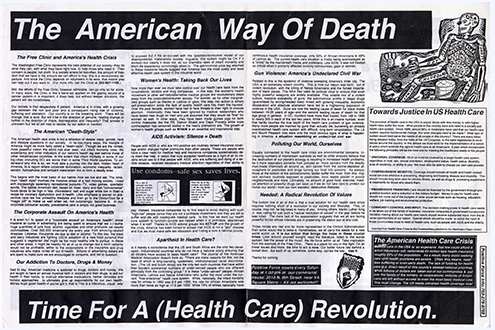

D.C. continued to be a canvas for humanity’s highs and lows, continuing its climb out of the infamy that buffeted the lives of its citizens for years. The per-capita homicide rate climbed again, nearing the 1991 all-time peak after declining in 1992.8 Violent crime continued to have a deeply unequal impact with Black men and women as victims in over 93% of murders in the year.9 Two stories dominated headlines on violence in the District: a series of attacks and murders in Northeast committed by a man termed in the press as “the shotgun stalker” and the killing of four-year-old Launice Smith.10, 11 Mayor Kelly had been working to downsize the police force since taking office two years earlier, shrinking the department by 10 percent by April of 1993. In the wake of ongoing violence, however, the thought of further cuts proved unpopular.12 The mayor attempted to address this persistent issue by issuing a call for the National Guard to assist D.C. police, which was denied by President Clinton.13 Later in the year, after meeting with Attorney General Janet Reno, Defense Secretary Les Aspin, and Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, Lee Brown, Kelly asked for $14 million from Clinton to support crime-reduction efforts in the city.14

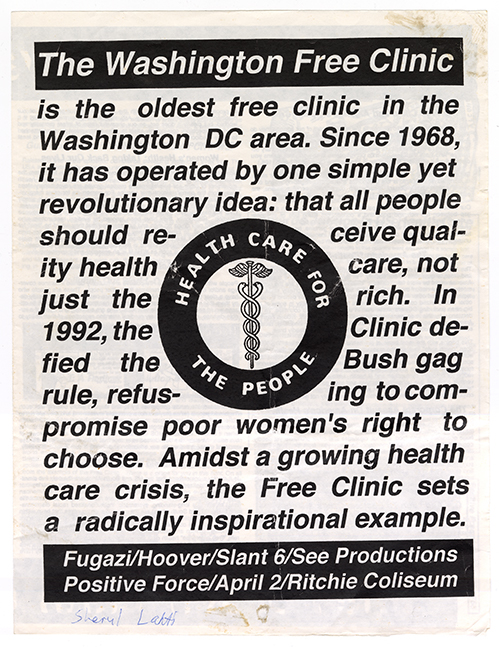

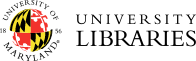

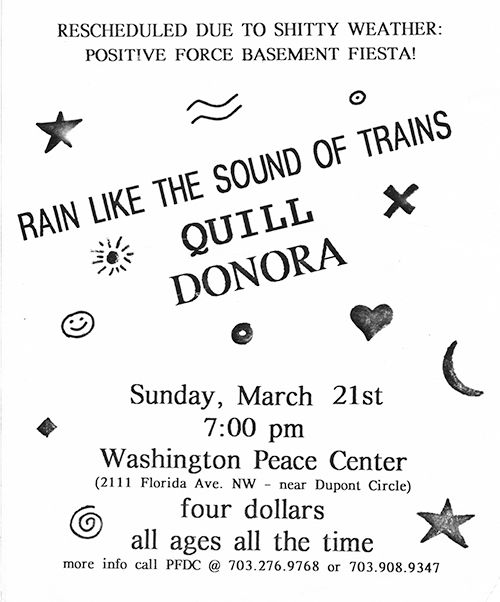

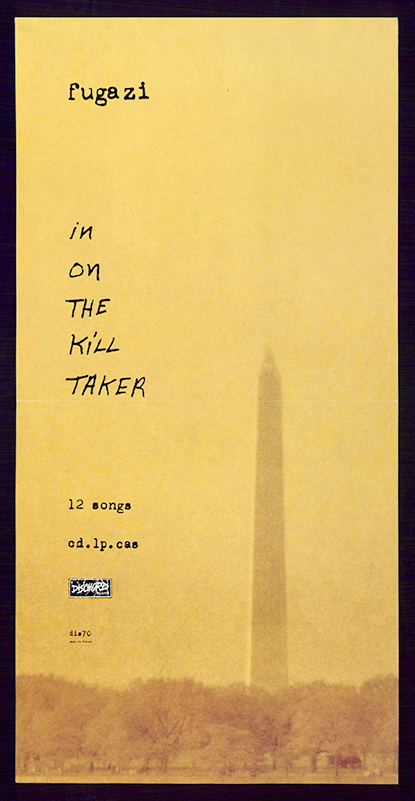

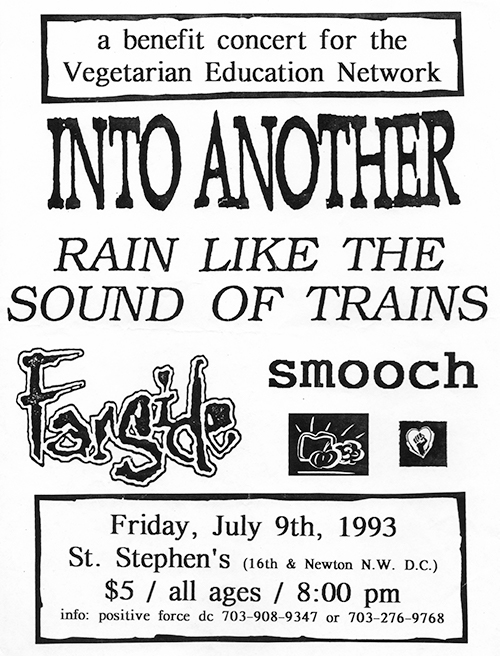

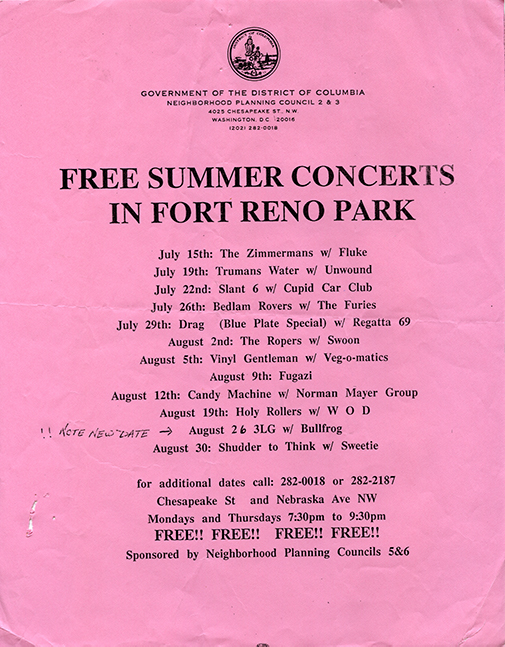

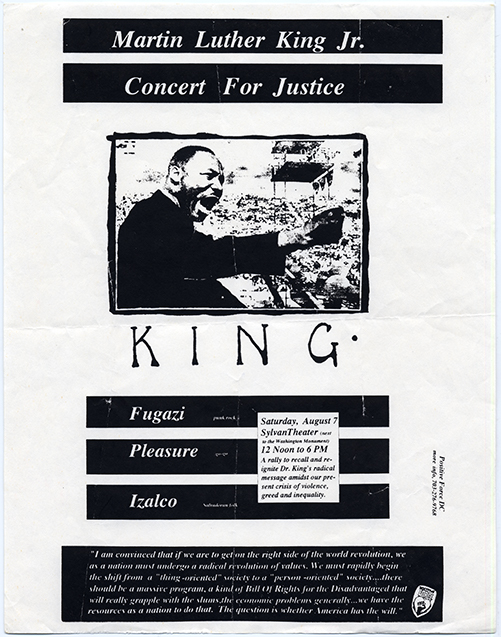

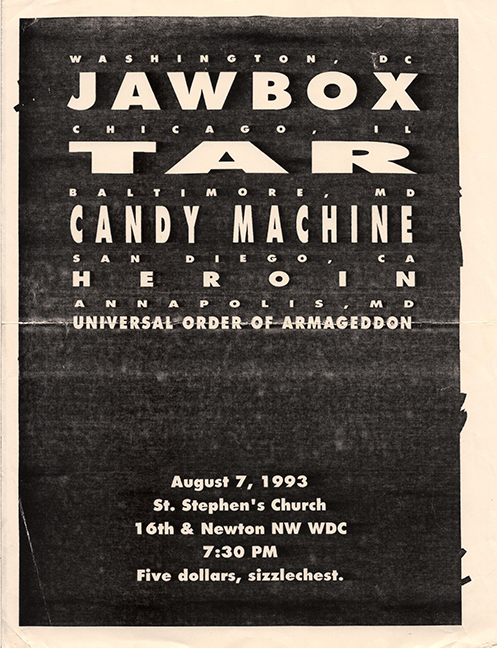

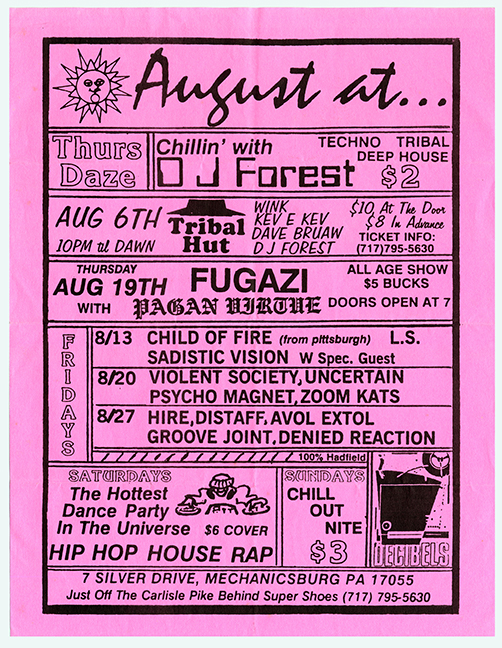

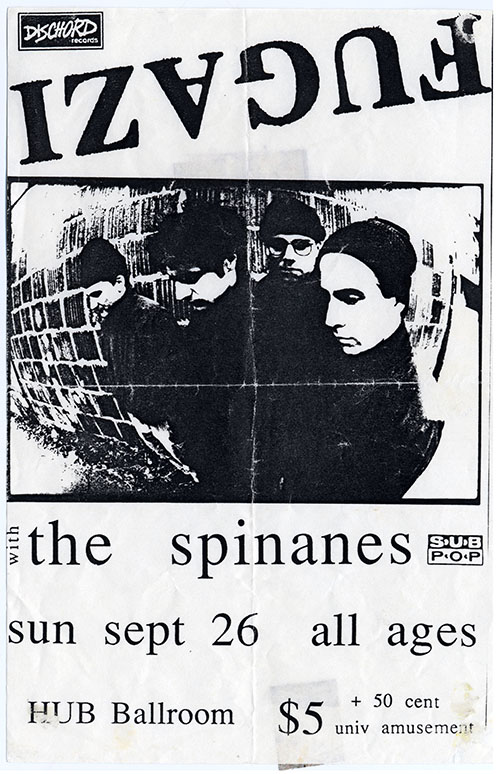

Against this backdrop, D.C.’s punk scene saw one of its highest points soon after the release of Fugazi’s album In On the Killtaker, which peaked at #153 on Billboard’s Top 200 Albums sales chart, a previously unthinkable encroachment of a D.C. punk into a mainstream realm.15 The band headlined a free concert on August 7 to five thousand fans at the Sylvan Theater in the shadow of the Washington Monument.16 Just two days later, the band played to thousands again, headlining another free concert, this time at Fort Reno Park in NW D.C. A lengthy feature on the band that week in The Washington Post marveled at how “rock’s royalty of the 90s”—members of popular alternative rock bands Nirvana, Hole, and R.E.M.—recently clamored to be in the band’s presence when Fugazi passed through the west coast on a recent tour. Pearl Jam vocalist Eddie Vedder was among alternative rock’s biggest stars and, when he arrived in D.C. for one of his band’s concerts, he skipped the usual tourist sites to, instead, make a pilgrimage to the homes of Fugazi members Ian MacKaye and Guy Picciotto, later remarking that he would put the former “up for sainthood.”17, 18

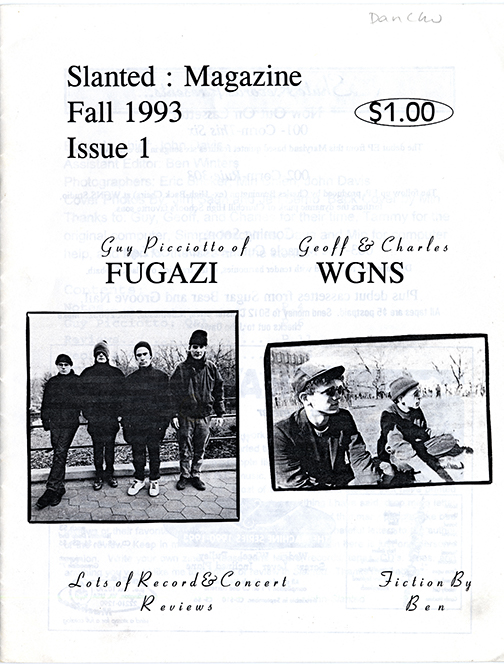

Fugazi shrugged off their growing fame, remaining restless creatively and. “It just seems like after a while some things get tired and some things need to be changed,” Picciotto told Slanted, a fanzine from suburban DC, in an interview that summer. “Punk rock, in the beginning, was a reaction to what the prevailing thing was, so I would hope people don’t just get locked into formulas. Once things get textualized they become a little boring after a while, so I’m always looking for something new.”

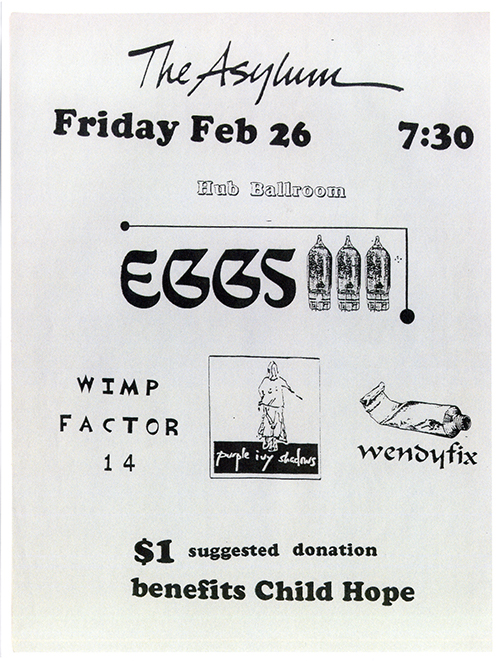

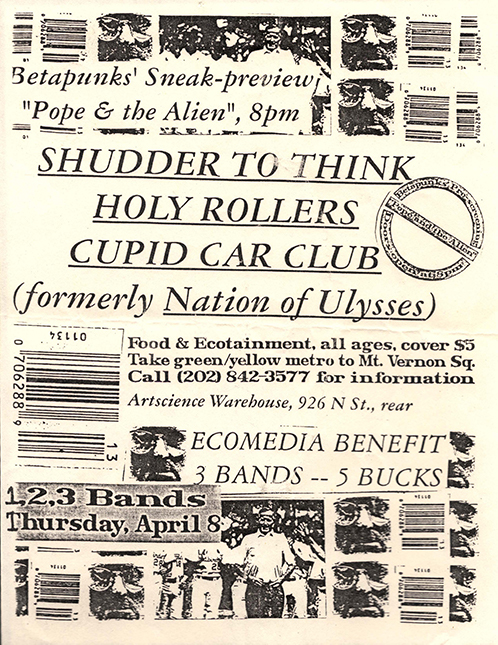

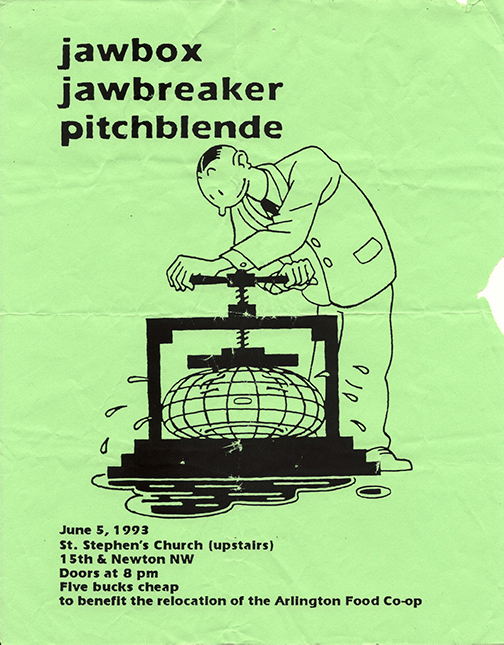

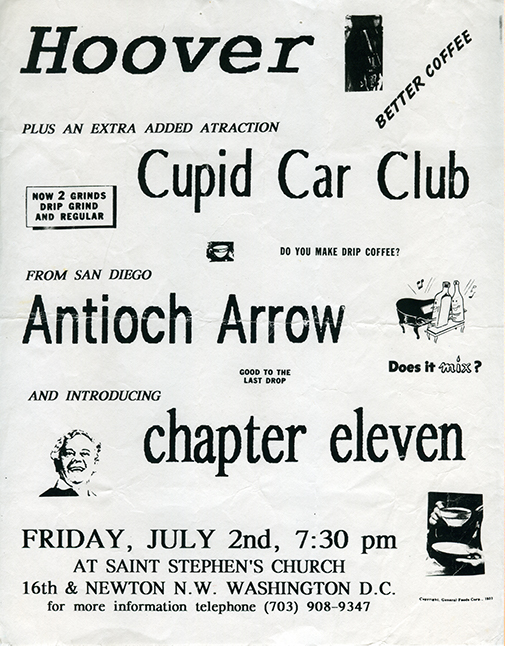

As with the preceding years, the bands composing D.C.’s punk scene had an increasingly national reach with their music. Cupid Car Club, made up of James Canty, Steve Gamboa, and Ian Svenonious of the recently-dissolved Nation of Ulysses joined bassist/vocalist Kim Thompson to release their debut (and only) EP, Join Our Club, on the Olympia, Washington-based label, Kill Rock Stars. Kill Rock Stars also continued releasing new music by the D.C.-linked bands Bikini Kill and Bratmobile. Closer to home, the Wilmington, Delaware label Jade Tree continued curating an emerging sound with a catalog covering a range of bands from the District, foreshadowing their later genre-defining releases on the label. While based in Delaware, Jade Tree began through a chance meeting of founders Tim Owen (who grew up just outside D.C. in Bethesda, Maryland) and Darren Walters at a show in D.C.19 While Jade Tree would become best known for releasing records from national emo and indie bands the Promise Ring, Joan of Arc, and Jets to Brazil, among others, the label’s earlier years were partially defined by the D.C. post-hardcore milieu through releases from Swiz, Pitchblende, Eggs, and Leslie.

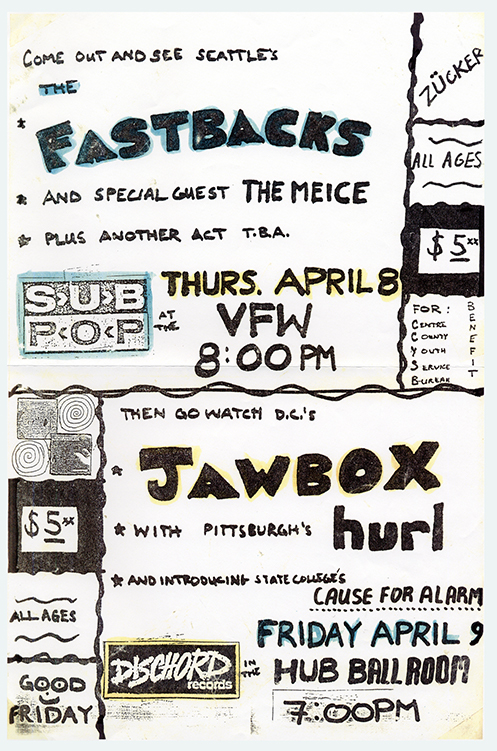

Aside from Fugazi, few other D.C. punk or indie rock bands could compare to the national reach Velocity Girl achieved through their debut LP, Copacetic, released in 1993 on Sub Pop.20 The label had been lifted from its financial strains due to the commercial success of Sub Pop-related groups like Nirvana, Soundgarden, and Mudhoney. While “noise” was the operative word in contemporaneous reviews of Copacetic, Velocity Girl's traditional pop sensibilities represented a stylistic evolution for the label.21, 22, 23 That a D.C. band would achieve major success on the record label that literally helped to define “grunge” marked a moment where D.C. was again an epicenter of American music.24, 25

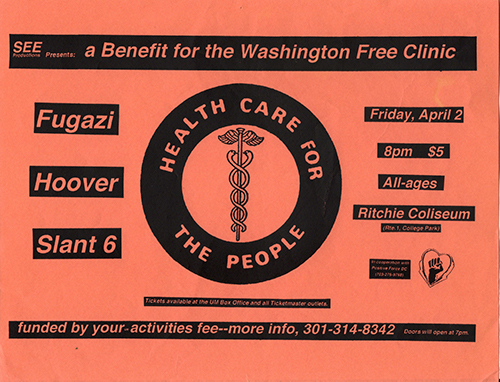

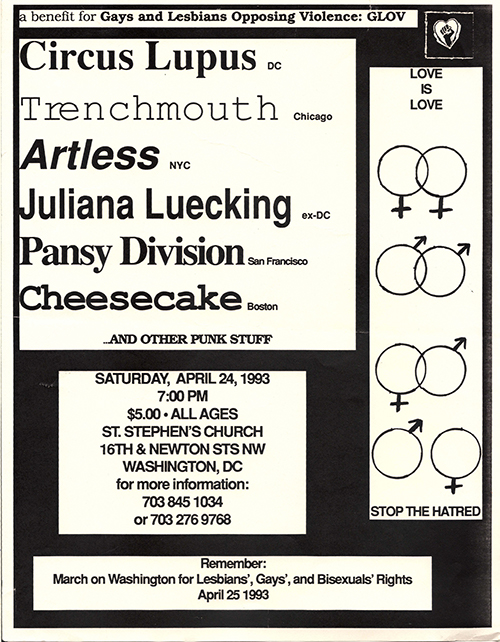

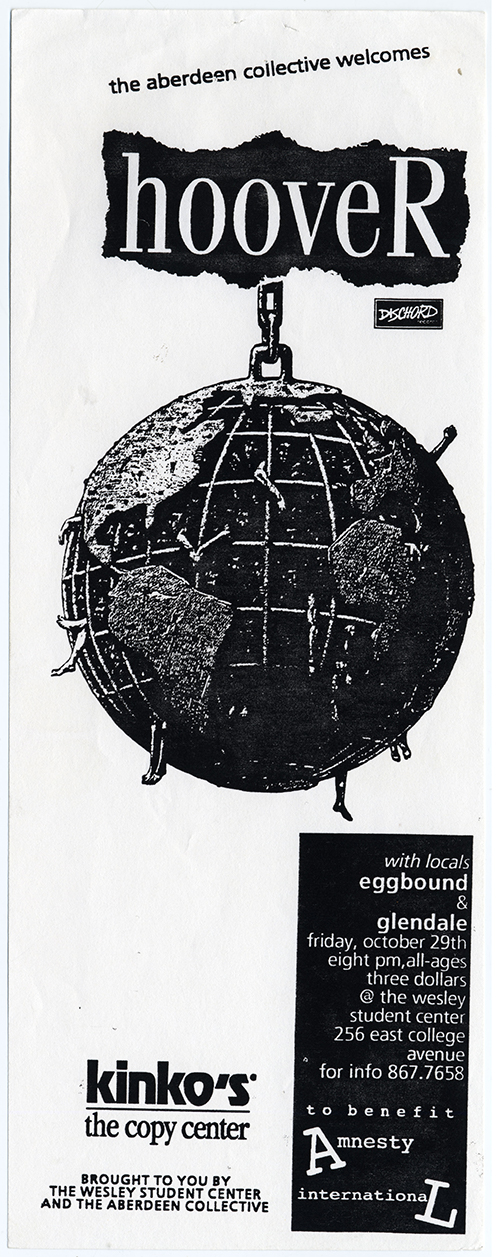

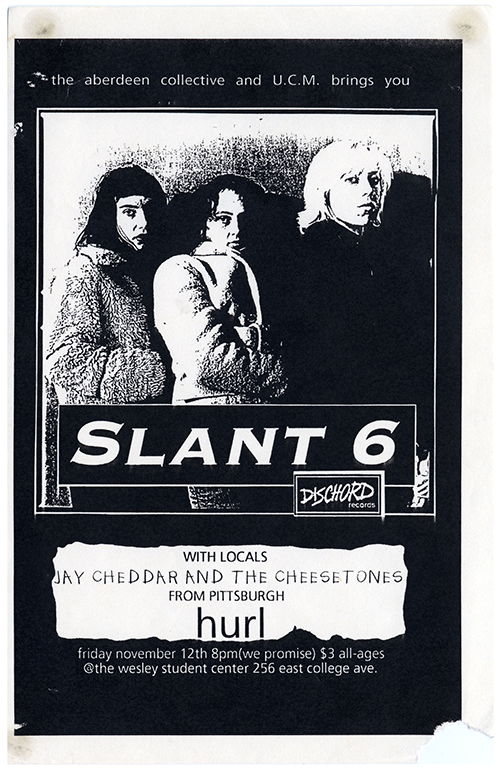

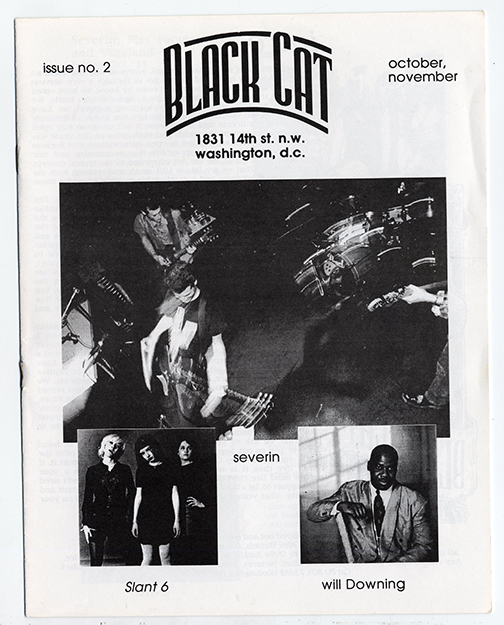

This is not to say that the local independent labels stopped becoming primary points of contact for the scene by 1993. While Fugazi remained the torch-bearers for Dischord and the DIY approach to the music business, the label continued representing an array of bands in the scene, new and old. This year saw the CD release of the 1982 compilation, Flex Your Head, which had become a critical testimony of the first wave of American hardcore punk. The reissue presciently understood the wave of punk collecting to come, as it was sold with a sticker reading “Dude! There is only ONE version of this CD and it includes ALL FOUR covers!” Dischord also continued looking forward, issuing music from many of D.C. punk’s most striking and innovative groups. Slant 6, fronted by Christina Billotte (previously of Autoclave and Hazmat) along with drummer Marge Marshall and bassist Myra Power, had formed the previous year and Dischord issued their self-titled debut 7-inch (highlighted by “What Kind of Monster Are You”) in 1993. Circus Lupus broke up this year but did release its second album in the summer on Dischord, Solid Brass, which captured the group’s dark, angular punk sound for a memorable last word.

Tsunami’s debut album, Deep End, was released on Simple Machines in the year’s first half.26 Paired with increased exposure touring as part of the Lollapalooza alternative music festival that summer, Tsunami and Simple Machines reached audiences far outside of the D.C. area. Simple Machines also continued their curated series featuring bands from within and without the label that had formed a constellation of artists. Inclined Plane, the finale in the Machines, series, arrived in 1993, featuring standout songs from Tsunami, Superchunk, Rodan, and Unrest. Following the end of the Machines series, Simple Machines took on their most audacious series to date. The Working Holiday series saw a new split 7-inch release issued every month in 1993, featuring two bands and “celebrating holidays and often-overlooked events in history.”27 As Simple Machines heads (and Tsunami bandmates) Jenny Toomey and Kristin Thomson wrote on the back of the first January release:

Who writes history? It can be fun to celebrate the traditional holidays, but why not look at these events with a different perspective. We want to learn about pivotal events from the past that are often forgotten - the actions of individuals or small groups that have changed history. Think about the suffragettes chaining themselves to the White House gate to demand the vote for women, the Stonewall riots that sparked gay & lesbian activism, Barney Clark accepting the artificial heart. Who’s to say what’s a real holiday? Why can’t we make our own anyway?

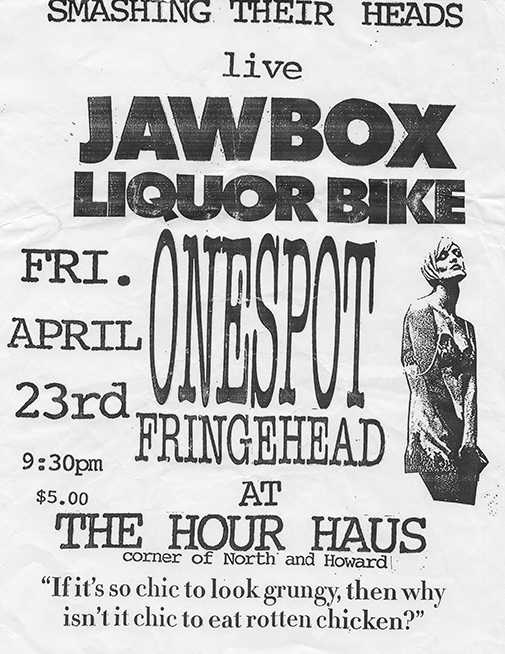

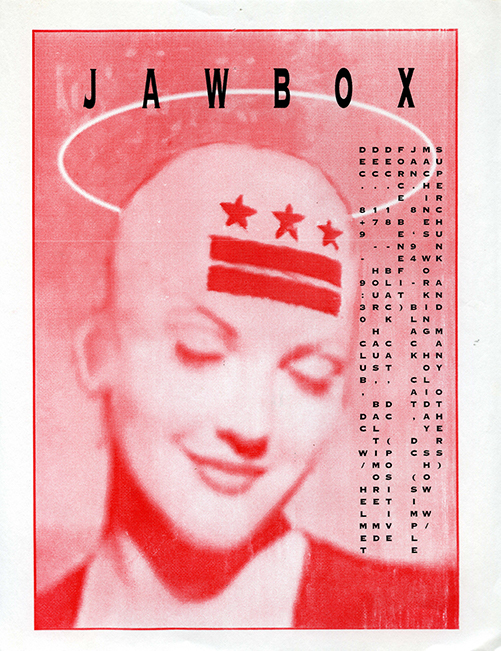

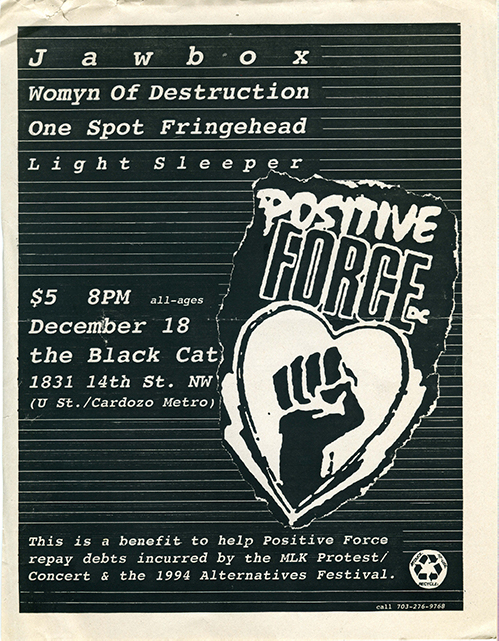

Featuring Jawbox, Pitchblende, Bratmobile, Tsunami, Lungfish, Eggs and many others from within D.C. and beyond, the Working Holiday series was a record club, but also a statement and a testament to making art, from the ground up, with friends, here. While the sound, look, and feel of the scene are ever changing, the throughline for the scene has and continues to be a dedication to the power of doing it yourself.

Further Listening

Bratmobile. Pottymouth. Kill Rock Stars, album.

Circus Lupus. Solid Brass. Dischord Records, album.

Cupid Car Club. Join Our Club… Kill Rock Stars, 7-inch EP.

Edsel. The Everlasting Belt Co. Grass Records, album.

Eggs. In State. Jade Tree, 7-inch EP.

Frodus. Tzo Boy. Gnome Records, 7-inch EP.

Fugazi. In On the Kill Taker. Dischord Records, album.

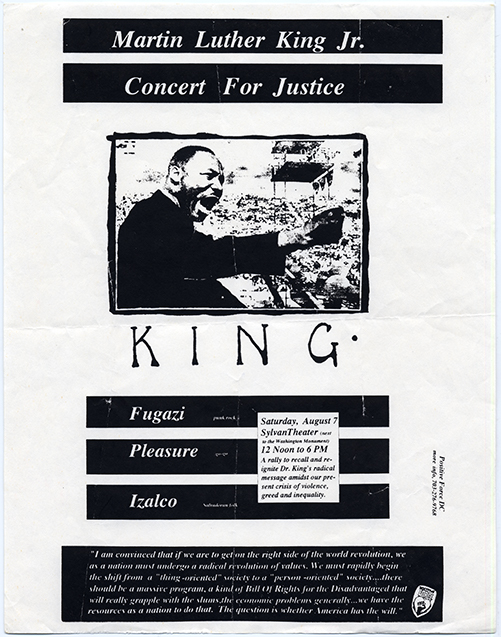

Hoover. Side Car Freddie/Cable. Hoover Union/Dischord Records, 7-inch EP.

Hoover. Hoover. Hoover Union/Dischord Records, 7-inch EP.

Hoover/Lincoln. Two Headed Coin. Art Monk Construction, split 7-inch single.

Jawbox/Edsel. Your Choice. DeSoto Records, split 7-inch single.

Leslie. All Tricked Out. Jade Tree, 7-inch single.

My Life in Rain. This is Your Ballistic Helmet. 50% Records, 7-inch EP.

Pitchblende. Kill Atom Smasher. Fist Puppet, album.

Pitchman. Smoke and Mirrors. Demo cassette.

Slant 6. What Kind of Monster Are You? Dischord Records, 7-inch single.

Swiz. No Punches Pulled. Jade Tree, discography compilation album.

Trusty. Cockatoo. Sidekick Records, 7-inch EP.

Trusty. “Kathy’s Keen” / “No One.” DeSoto Records, 7-inch single.

Tsunami. Deep End. Simple Machines, album.

Tsunami. Diner. Simple Machine, 7-inch single.

Unrest. Perfect Teeth. 4AD/Teenbeat Records, album.

Various. Echos From the Nation’s Capital (w/Edsel, High-Back Chairs, Revision, Sweetie, Trusty, Tsunami, Wingtip Sloat). Third World Underground, compilation album.

Various. The Machines (w/Velocity Girl, Edsel, Geek, Holy Rollers, Nation of Ulysses, Jawbox, Tsunami, Severin, Autoclave, Circus Lupus, Unrest). Simple Machines, compilation album.

Velocity Girl. Copacetic. Sub Pop Records, album.

Materials are drawn from the Chris Baronner digital collection on D.C. punk, Aaron Claxton collection on D.C. Hardcore, John Davis collection on punk, D.C. punk collection, and the D.C. punk and indie fanzine collection.

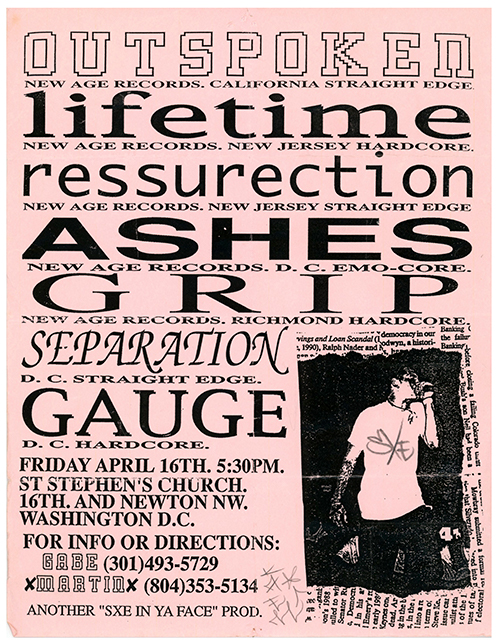

Tap or hover over an image to learn more.

FLIERS & POSTERS

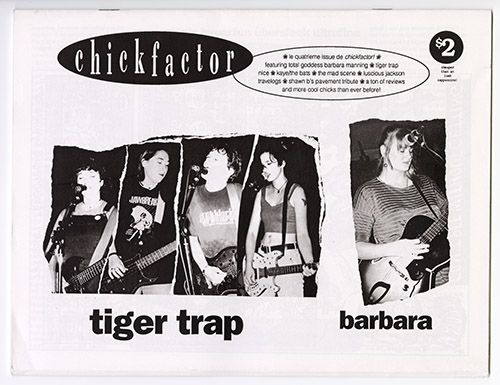

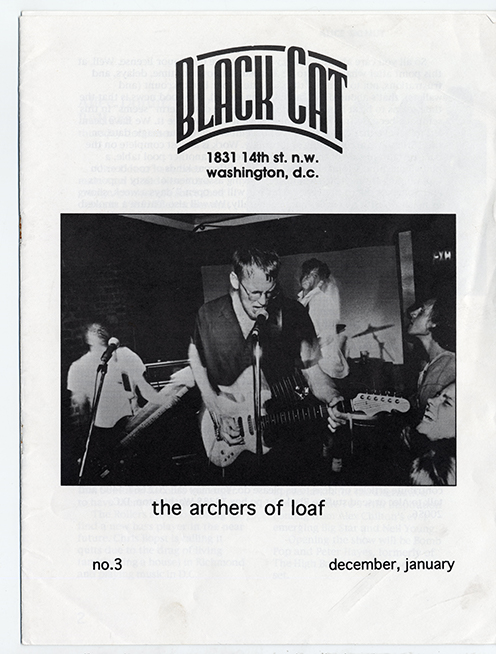

ZINES

EPHEMERA